Strawberries in Tudor and Stuart England

As we enjoy the lush bounty of summer here in the UK, it’s time to celebrate one of the most iconic, fleshy and delicious fruits of the English summertime – the humble strawberry! I am a BIG fan! Every year I eagerly await the coming of June when strawberries really come into season (I never eat them before June, they are invariably tasteless) and I can enjoy a bowl, topped with lashings of cream. But what about our Tudor fore-fathers? How did they enjoy their strawberries? For those aspiring Tudor chefs among you, its time to get back in the kitchen with Brigitte Webster of TudorExperience.com and create an authentic Tudor recipe using strawberries – perfect for a summer’s day!

Note: If you want to hear Brigitte talk about strawberries in Tudor England and see the recipe being made in her country kitchen at the Old Hall, then check out the link at the end of this blog.

Strawberries in Tudor England

In Tudor England, strawberries were enjoyed at all levels of society and unusually for the time, enjoyed eaten uncooked. The medieval belief that raw fruits were positively dangerous was still rife, despite the great developments in gardening and orchards during the Elizabethan period.

In 1583, readers of “The Schoolmaster or Teacher of Table Philosophie” were told how Galen, the great second-century philosopher, only contracted numerous and lasting ailments after eating raw fruits, but after giving them up, ‘had never any sickness’. For this reason, most fruits were eaten after being either cooked for immediate consumption or preserved, so that they could be enjoyed throughout the whole year.

‘Rawe crayme undecocted eaten with strawberries…. is a rural manner basket’ wrote Andrew Boorde. Dr Butler considered that ‘Doubtless God could have made a better berry, but doubtless God never did’. James I was often so ravenous for them that whenever Mr French, his gardener, tried to introduce the first of the new season’s crop with a small speech, the king ‘Never had the patience to hear him one word but his hand waist the basket’.

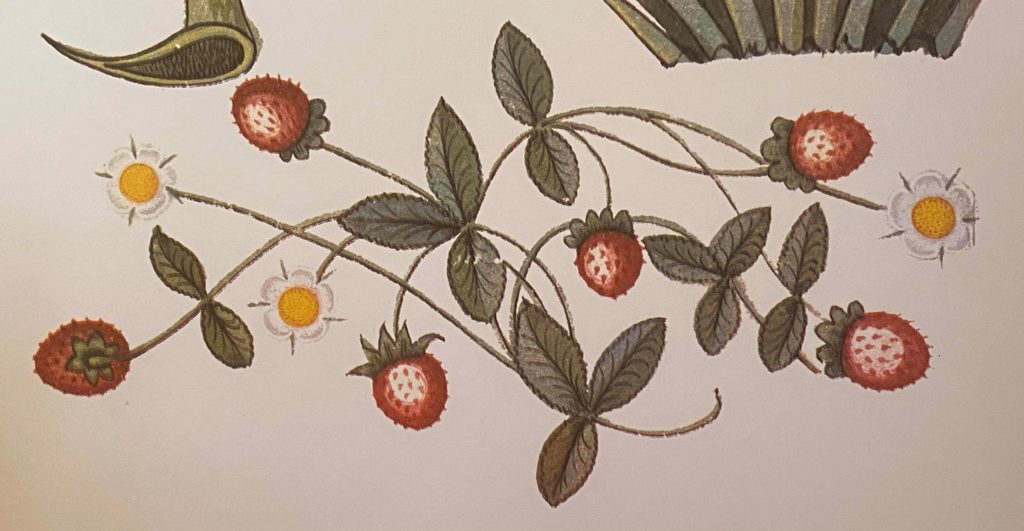

Up to the early seventeenth century, all the strawberries grown in England were the small, brilliantly scarlet, wild variety. This was the case whether they were whether gathered from the countryside or grown in the garden. The larger ‘Virginian” variety, the forefather of our modern strawberries, was introduced later in the seventeenth century from the new American colonies.

Strawberries evoked temptation and Hieronymus Bosch used strawberries as a symbol of fleeting and dangerous pleasures in his “Garden of Earthly Delights“, circa 1505. However, in contrast, in Christian art, strawberries lost their sinister aspect; with no pips, or peel, they were presented as the perfect fruit, symbolising the Virgin. The white flower and the red fruit represented purity and martyrdom; the threefold leaves the Trinity.

Strawberry Delights: Titbits from Tudor England

Here are some Tudor facts and descriptions gathered from various sixteenth century sources:

- The old English name “streawberige’ derived not from straw but from the runners strewing fresh plants in all directions.

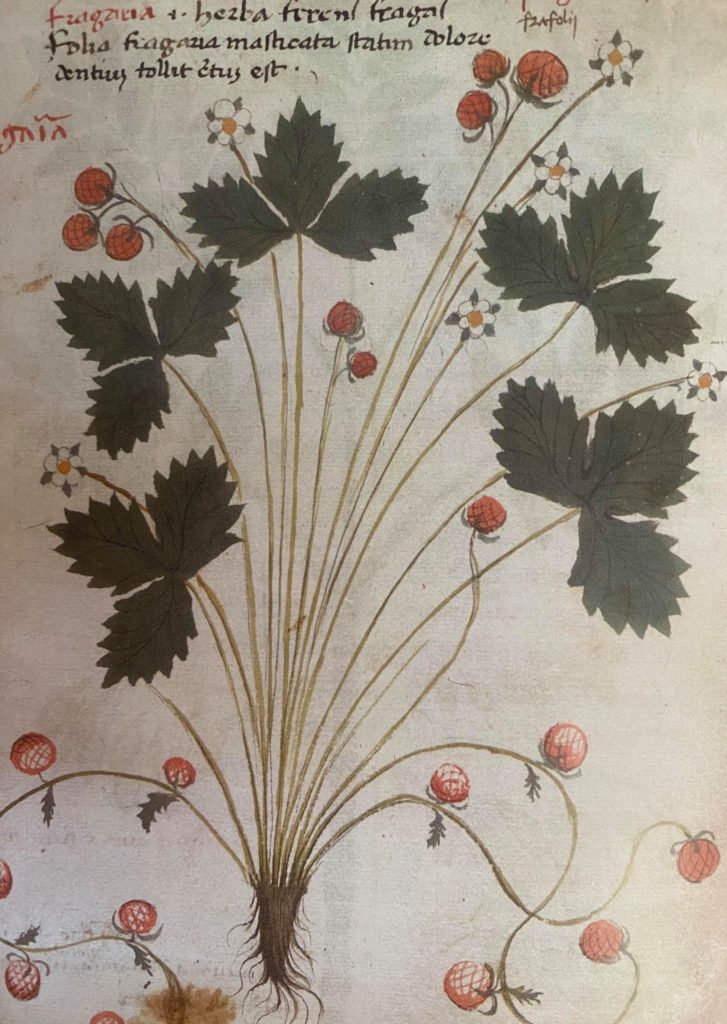

- The first Herbal published in England featuring the strawberry was by Peter Treveris in 1526.

- In “The Names of Herbes” by William Turner in 1548, the entry for strawberries simply states, that every man knows well enough where they grow.

- Thomas Hill recommends planting strawberries among rose bushes in his “The Gardener’s Labyrinth”, which was published in 1577. He also lists red, white and green strawberries and insists that the wild ones growing in the wood are the best.

- Shakespeare mentions strawberries in several of his plays such as Richard III (Act III, sc4), Henry V (Act 1, sc1) and Othello (Act III, sc3)

“Have you not sometimes seen a handkerchief Spotted with strawberries In your wife’s hand?”

Medicinal and Culinary Uses of Strawberries in Tudor England

In his 1597 Herbal, John Gerard lists red, white and green strawberries and says that the wild strawberry is barren of fruit. He states that strawberries are found in both gardens and in the wild. He rates the fruit as cold and moist but the leaves as dry and cool. According to him, the ripe fruit quenches the thirst, cools the heat of the stomach and the inflammation of the liver, as well as taking away the redness and heat of the face – if used often!

During the third quarter of the sixteenth century, many new recipes were developed for preparing fruits for banquets. These were published in a series of innovative cookery books, specially written for the benefit of fashionable and wealthy ladies.

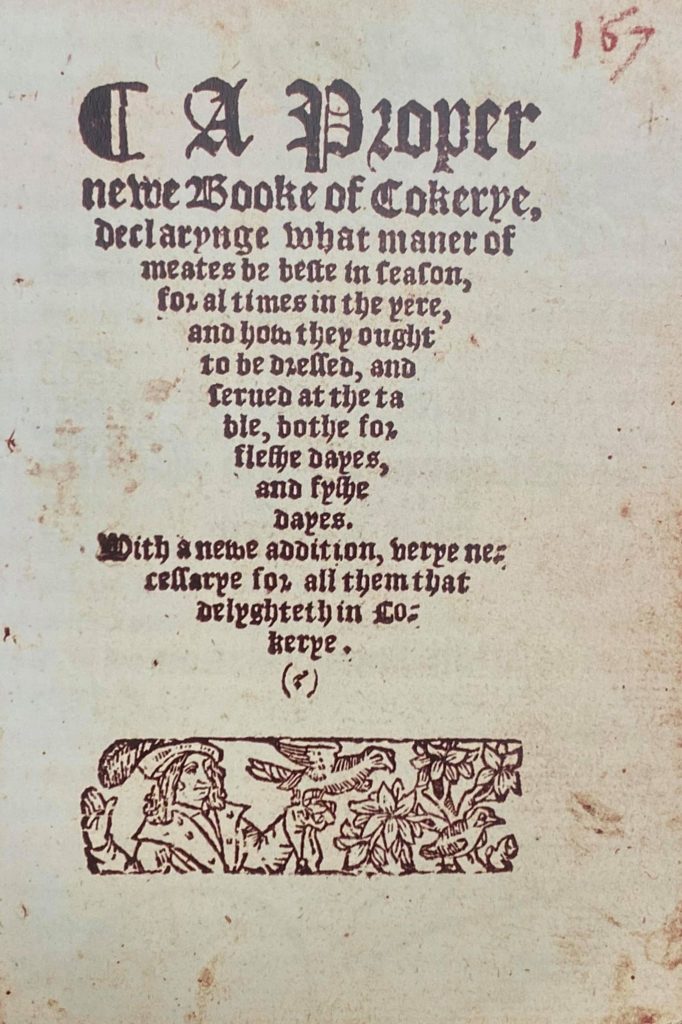

Today we take a closer look at the second earliest cookery book in the English language – and the only one known in print during Henry VIII’s reign. ‘A Proper Newe Booke of Cokerye, by an unknown author, was first published in 1545. Only one copy of this first print is still in existence at the University of Glasgow. (In the video I mention Edinburgh – sorry!). The copy we are using today is from 1557 and is held at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. Other copies from the same year are in the British Library.

The history of this amazing, early cookery book is much more than a collection of recipes; this volume is also the love story of two Norfolk-born people and an account of how the Reformation affected people’s lives and happiness.

Matthew Parker was born around 1505 in Norfolk and started University at Corpus Christi in 1521. By 1527, he had been ordained as a priest and in 1528 he became a Fellow there. His life started to change when he became Henry VIII’s chaplain and, in 1544, he started his a new career as the Master of the College. It was around then that he met (his future wife) Margaret and they fell in love – although priests were forbidden to marry. Despite that, they remained exclusively faithful to each other.

Seven years later, when Edward came to the throne, priests were allowed to have a wife under the new Protestant faith. Margaret moved into the college as Matthew’s wife. But their happiness was not to last. Following Edward’s early death, Mary I re-introduced the old ways and rescinded the new law that had allowed members of the priesthood to marry.

Matthew had to resign from his prestigious post and withdrew into obscurity, living in the country with his wife under fairly modest conditions. Margaret would have had to run her own household and it is during this time that she was most likely to have obtained this recipe book. Their roller-coaster life was to turn yet again when Elizabeth followed Mary on the throne. As it happened, Matthew had formerly been chaplain to Elizabeth’s mother, Anne Boleyn. On Elizabeth’s accession, it was Matthew that she asked to be her first Archbishop of Canterbury! Even though Elizabeth did not encourage marriage for priests, she respected him and Matthew and Margaret were allowed to live happily ever after!

Here is one recipe from that collection. It is a simple recipe that can be tackled by a beginner. It is delicious, easy to make and the perfect Tudor treat for a hot summer’s afternoon!

TO MAKE A DYSCHEFULL OF SNOWE (Modernised Recipe) :

Here are the ingredients that you will need:

Ingredients:

4 large eggs

200g sugar

Some rosewater

100ml double cream

2lbs (1kg) fresh strawberries

Small sprigs of rosemary

Tudor wafers or ratafia/amaretti biscuits

Method:

Wash strawberries and strain through a sieve (or use a food blender to get slightly different textures).

Beat the egg whites (making sure that there is absolutely no egg yolk or grease in the bowl before you begin) and then add sugar carefully.

Whip the cream in a food mixer and add to the stiffened egg whites.

Fold in the strawberry puree, decorate with biscuits and rosemary sprigs dipped in ‘snow’.

Serve and enjoy!

WARNING: Please be aware that the use of raw egg whites may put you at risk of salmonella food poisoning if the eggs come from non- vaccinated chickens.

The Great Tudor Bake Off on YouTube

If you want to hear and see Brigitte talk about strawberries in Tudor England, and prepare ‘A Dyschefull of Snowe’, then click on the image below. Don’t forget to subscribe to the Tudor Travel Guide’s YouTube channel for loads more Tudorlicious videos from The Tudor Travel Guide.

Sources and further reading:

The Gardener’s Labyrinth – Thomas Hill, 1577

The Grete Herball – Peter Treveris, 1526

Herbal – John Gerard, 1597

The Names of Herbes – William Turner, 1548

A Proper Newe Booke of Cokerye – 1557

The Medieval Flower Book – Celia Fisher

Botanical Shakespeare – Gerit Quealy

MS Ashmole, 1504 – Bodleian Library