Sheffield Manor: Wolsey and the Spectre of Death

In the story of Wolsey’s final days on Earth, Sheffield Manor (situated in Sheffield Park) is a pivotal location. It would later become famous as one of the prisons used to house Mary, Queen of Scots, during her protracted incarceration in England. However, in our story, it was at Sheffield Manor that the very first manifestation of the illness that finally took the Cardinal to his grave became apparent. The florid account of his symptoms has been preserved for us in George Cavendish’s Life of Wolsey. The account is so distinctive, even to a modern doctor, that this document provides us with a rare and accurate insight into the cause of the death of Henry VIII’s erstwhile first minister.

In this second blog in a series of three, we continue to follow the Cardinal southwards toward London. Having been arrested for high treason at Cawood Castle in North Yorkshire, Thomas Wolsey was taken first to Pontefract (Pomfret) where he was lodged at the abbey, much to Wolsey’s relief. (He had feared being taken to Pontefract Castle, which had a fearsome and blood-soaked reputation as a place to dispose quietly of one’s high-status enemies!)

From there, Cavendish records that the cavalcade continued onwards to Doncaster. Clearly, careful planning was afoot. Those in charge decided that Wolsey should arrive during the hours of darkness. So many people had taken to following the sorrowful procession ‘weeping and lamenting’ that they wished to avoid more unnecessary scenes of hysteria. Although Wolsey entered the ancient town by torchlight, the plans were thwarted. The usual crowds amassed ‘with candles in their hands’, crying out, ‘God Save Your Grace, God Save Your Grace, my good Lord Cardinal.’

According to Cavendish, the escort and its prisoner were heading for one of the city’s religious houses, Blackfriars, where they were lodged that night. The following day, the journey continued. Wolsey was being taken to ‘Sheffield Park’, one of the principal residences of the Earl of Shrewsbury. In fact, the Cardinal was to spend the next 18 days at the manor, well-housed and honoured as befitted his status. There are incredible details to share from George Cavendish’s account. As Wolsey’s Gentleman Usher, he was never far from the Cardinal’s side.

In the rest of this blog, we will learn about these events, so often recounted. But this time, we put them in the context of where they occurred. I will share with you some of what is known about the now largely lost manor house so that Cavendish’s words can come alive in your imagination. Once more, we can draw back the veil of time, walk through the grounds, rooms and galleries of this once-great Tudor mansion, and witness the Cardinal’s cavernous despair.

Cardinal Wolsey Arrives at Sheffield Manor

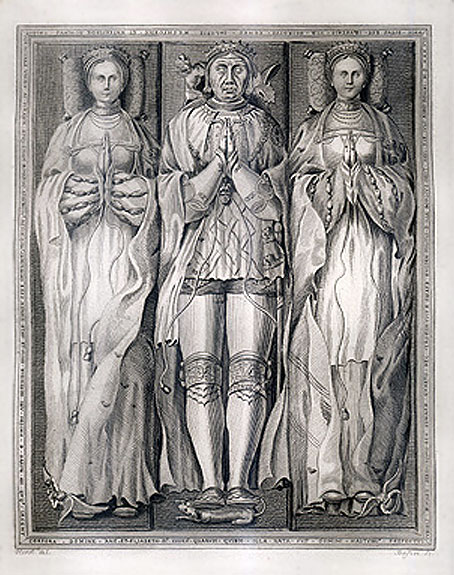

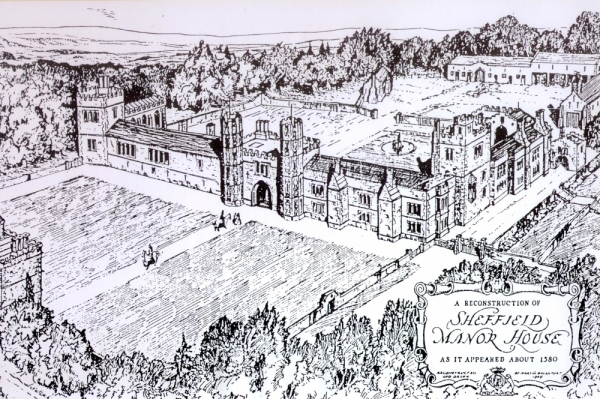

Wolsey was greeted at the gates of Sheffield Manor on 8 November 1530, by George Talbot, the 62-year-old, 4th Earl of Shrewsbury and his second wife, Elizabeth, They were accompanied by a train of her gentlewomen and ‘all of my lord’s gentlemen and yeomen’. By that time, a grand Tudor manor house was on-site, fashioned from the remodelling and augmentation of an earlier hunting lodge. This phase of work was likely undertaken by the 4th Earl, probably before 1516. Perched on an elevated promontory of land, it overlooked Sheffield Park, which was one of the country’s largest at around 2500 acres. This park provided income and was a pleasing pastime for the Earl of Shrewsbury, his family, and his guests.

So, at the time of Wolsey’s visit, Sheffield Manor was a newly renovated house and one of two principal residences of the Shrewsbury family in Sheffield, the other being the now entirely lost castle. Fortunately, several accounts and an early plan survive.

The manor was well known for its avenue of walnut trees, which apparently formed a dense canopy that connected the lodge to Sheffield Castle. That must have been a natural architectural delight! From these sources, we also know that the house was made of brick and timber and was arranged fashionably around two courtyards: an outer, or Great, court and an inner one. There were also two gardens and three yards, covering over three acres.

The Great Court was almost entirely square and covered two acres. The main west-facing frontage of Sheffield Manor looked down upon it. From here, two octagonal, red-bricked towers flanked the principal access to the inner court. This gatehouse gave access to a ‘noble flight of steps which led to the door that opened into the Great Gallery’ (where Wolsey would be housed, as we shall hear shortly.)

At the gates of Sheffield Manor, the two men greeted each other courteously and with some affection, Wolsey taking another opportunity to declare his innocence, that his ‘demeanour and proceedings’ had always been ‘just and loyal’ toward his ‘sovereign and liege lord’. Shrewsbury tried to comfort the Cardinal, telling Wolsey that he had received letters from the king and that he was to be treated not as a prisoner but ‘as my good lord and the king’s true faithful subject’.

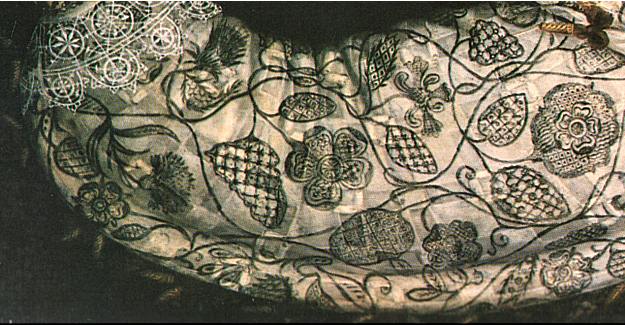

Relieved, no doubt, Wolsey walked arm-in-arm with his host as Shrewsbury escorted the Cardinal to his chambers. These chambers are described in some detail in Cavendish’s accounts, and from what we know of the lost manor, we can pinpoint exactly where they were: in ‘a fair chamber at the end of a goodly gallery, within a new tower.’ Shrewsbury had the gallery temporarily partitioned off by a ‘traverse of sarcenet’ (a soft silk material), which had been placed across the middle of this large chamber. In doing so, Cavendish states: ‘one part was preserved for my lord and the other part for the earl’.

The scant above-ground remains of this once great house and later archaeological excavations allow us to pinpoint the exact position of the gallery. This ran north-south, fronting onto the great court on one side and the inner court on the other. The tower that is mentioned in Cavendish’s account was at the very northern end of the aforementioned gallery. In these rooms, Wolsey was lavishly housed and lacked for nothing. From Cavendish, we hear that he enjoyed ‘goodly and honourable entertainment’ but that the Cardinal refused to indulge in earthly pleasures, such as hunting, but instead resorted diligently to prayer. He ate in his chamber (in accordance with his high status), with meals that included dishes of venison from the park and roasted wardens (pears).

While dining in his chamber with several of the Earl’s men and chaplains one evening, Wolsey took ill. Cavendish, who was ‘dressing the wardens’ at the time, noted how the colour drained from the Cardinal’s face. Enquiring discreetly about his master’s health, Wolsey replied that he was ‘suddenly taken about the stomach with a thing that lieth across my breast as cold as a whetstone. Wolsey diagnosed that it was ‘just wind’, but when the symptoms persisted, he asked his Gentleman Usher to go to the apothecary and enquire if he had ‘anything that would break wind upward’.

After some to-ing and fro-ing, in which Cavendish reported on Wolsey’s request to the Earl and the Earl, in turn, summoned the apothecary with his remedy, Cavendish was finally able to make his way back to the gallery and the Cardinal’s privy chambers in the Tower. Wolsey had not moved, clearly in considerable discomfort. Having tried the ‘white confection’ in front of his master (presumably to show it was not poison), the Cardinal ‘received it wholly altogether at once’ and immediately ‘he broke exceedingly much wind upwards’ before heading off to prayer, as he usually did after dinner. Unfortunately for the Cardinal, it was not just wind. Cavendish tells us that while at prayer, he was soon hit by a bout of diarrhoea (which the Tudors called ‘lask’).

While he was ‘at his stool’ (toilet), the Earl summoned Cavendish to tell him that Sir William Kingston had arrived with 24 guards to escort the Cardinal to London so that he may ‘try himself and his truth’. While the king had written that he still held the Cardinal in high regard and that he should be treated with all honour, both the Earl and Cavendish rightly believed that Wolsey would see this as a dark turn of events, for Sir William Kingston was Constable of the Tower of London.

It was left to Cavendish to break the difficult news. Wolsey’s Gentleman Usher found the Cardinal ‘sitting at the upper end of the gallery, upon a packing chest of his own with his beads and staff in his hands’. Despite George’s protestation that Wolsey had nothing to fear from the king, the Cardinal had seen too much of the world to be pacified so easily, telling his Usher that he could see ‘more than ye can imagine or do know.’ In other words, Wolsey was no fool, nor was he naive. He knew how these things worked; he had seen it all before.

Preparations were made ready for the next day. The journey toward London would continue, this time under the command of Sir William. However, Wolsey was worn out. The diarrhoea, which had struck him down shortly after dinner, continued through the night until, by the next morning, Cavendish reports that he had had over 50 stools, leaving the Cardinal ‘very weak’. However, more tellingly, we hear that the stools were ‘wonderous black’ (which Tudors called Choler Adustum). As an ex-physician, I will speak more about the cause of this in the next and final blog of this series.

In the meantime, Wolsey knew the symptoms were serious, declaring, ‘If I have not some help shortly, it will cost me my life’. A physician who happened to be visiting the Earl concluded that Wolsey would not live past four of five days. Significantly weakened, the Cardinal rested for one further day at Sheffield Manor. Finally, he took up his journey. Along the way, he grew ever weaker, ‘waxing so sick’ that by the time he arrived at Leicester Abbey, he knew the end was drawing rapidly closer.

Do join me next week for the final blog in this series of three. We will find out more about the place in which Thomas Wolsey died and explore the fascinating details of the Cardinal’s final hours.

In the meantime, if you are visiting Sheffield, why not visit the site of Sheffield Manor. Check out this link to find out more.

Sources

Sources I have found useful in writing this blog:

The Life of Wosley, by George Cavendish

Notes on Sheffield Manor by Thomas Winder. The Journal of the British Archaeological Association

Excavations at Sheffield Manor Lodge: 1968-80, by Dawn Hadley & Deborah Harlan

The History of Sheffield Manor Lodge by Green Estate and Sheffield Manor Lodge.

Time Walk Project: Promoting Sheffield’s Heritage by David Templeman

Thank you for such a lovely story, can not wait to read the rest!

Oh, thank you! You are welcome.

Thank you for this. To my shame, as a Sheffield lass in exile..didn’t know of this part of the story…and now need the final chapter.

This is fantastic, thank you for your writing! I’m researching the Manor area as family members lived here in the 1850’s, so very useful background! It’s great

Glad you enjoyed it! Thanks for letting me know.