Inchmahome Priory: The Romantic Refuge of the Scots Queen

This month, The Tudor Travel Show podcast celebrates the life of Mary Queen of Scots. We will be delving into some of the most iconic places in which she lived during her time in Scotland. Of course, the tale is one of two halves. Mary’s first stint in Scotland covers her early childhood. In the podcast, we will be focusing on two locations that relate to this time: Linlithgow Palace, the place of her birth, and Stirling Castle, which, for all intents and purposes, can be considered to be Mary’s childhood home. It was from Stirling that Mary was taken by her mother to Inchmahome Priory to escape England’s ‘rough wooing’ of the infant queen, and it is this location that we shall cover in today’s blog.

While Mary only remained at the priory for a fleeting three-week period during the autumn of 1547, it is such a romantic spot to visit that it is worthy of being included on any time traveller’s itinerary.

Note: In writing this blog, I am deeply indebted to Catherine Vost, a historian who has had a lifelong interest in Inchmahome Priory and has studied the site extensively. Catherine generously gave of her time in speaking with me and sharing some of her notes about the location, the output of which is woven into the writing below.

A Brief History of Inchmahome Priory

Inchmahome Priory is located on an island in the Lake of Menteith, close to Aberfoyle. It terms of our story, its geography is highly relevant. Sited some 15 miles to the west of Stirling Castle, its remote location, deep into the heart of Scotland, made it an ideal refuge for Mary’s mother, Marie de Guise, to bring little Mary at a time when the English were pressing for the young queen’s hand in marriage. As mentioned above, this is now known infamously as the ‘rough wooing’ of the Queen of Scots. More on those events shortly…

According to Catherine Vost, the medieval priory that was founded in 1238 by Walter Comyn, 4th Earl of Menteith, ‘was probably predated by an earlier Christian monastery’. Given its isolated and dreamy location, it is easy to see why it had become established as a place of spiritual reflection and worship. Indeed, the name itself comes from the Gaelic Innis MoCholmaig, meaning Island of St Colmaig; it was also known as The Isle of Rest. Thus, it would remain so for the next 400 years: a peaceful idyll and home to an order of Augustinian Black Canons, their patrons, benefactors, parishioners and visitors.

However, with the decline of Catholicism in the sixteenth century, monastic life slowly but surely began to ebb away. The heads of religious foundations subsequently became appointees of local landowners. In 1547, John, Lord Erskine, later the Earl of Mar, was appointed as such. He also happened to be Mary’s guardian as Regent of Scotland. It was on account of these connections that Mary was brought to Inchmahome when English incursions across the border threatened her safety.

By the mid-1500s, shortly after Mary departed for France, the Protestant Reformation in Scotland finally brought monastic life to a close. According to Catherine, ‘the land was leased to a lay family, after which it became, for all intents and purposes, the heritable property of the Erskines’.

Mary’s Flight to Inchmahome Priory

The events which culminated in Mary’s flight to Inchmahome began some four years earlier, shortly after the birth of the Scots queen in December 1542. Reeling from the crushing defeat by the English at the Battle of Solway Moss, when much of the cream of Scotland’s nobility perished, the Scots acquiesced to Henry VIII’s petition for the betrothal of little Mary to Henry’s five-year-old son, Edward.

It would have been a powerful dynastic union, replicating the one Henry VII had successfully arranged between his daughter and Mary’s grandfather, James IV. The Treat of Greenwich, which sought to bind the youngsters together, was signed on 1 July 1543. Mary was not yet one year old. Although some Scottish nobles favoured the union, others, including Mary’s mother, preferred an alliance with France and the Papacy. As a result, a good deal of prevarication ensued. This ultimately ended with the Scottish Parliament rejecting the agreement in December of the same year.

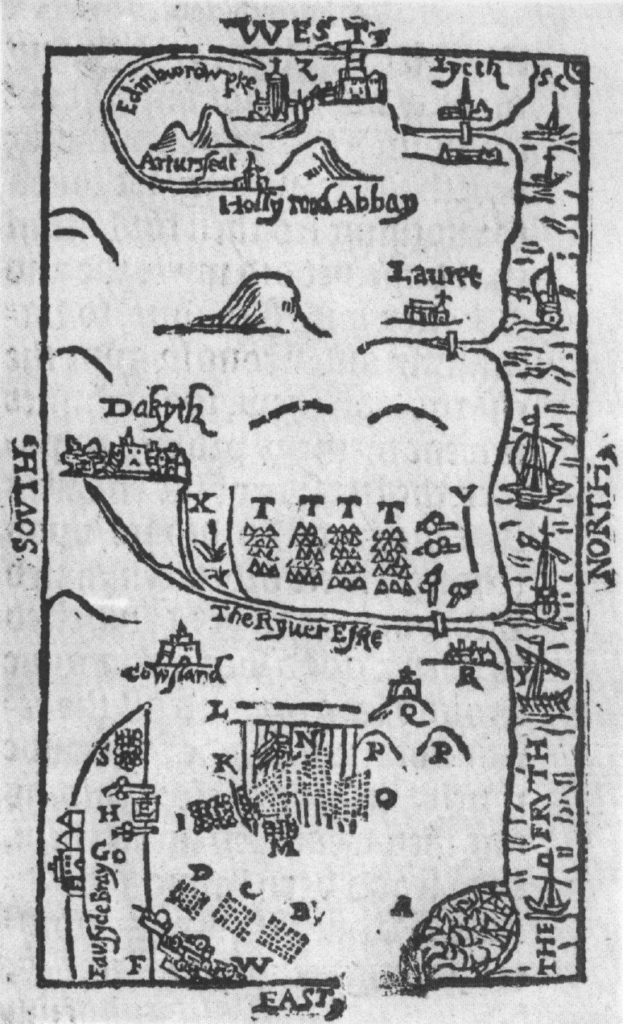

Furious at the deceit, Henry VIII began what would turn out to be an eight-year campaign against the Scots. This campaign became known as the ‘rough wooing’, and although Henry died in January 1547, Lord Protector Somerset continued to press the Scots for their adherence to the treaty. This eventually culminated in the catastrophic slaughter of the Scots army at the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh (at Musselburgh, just outside Edinburgh) on 10 September 1547.

To understand the scale of the defeat and why Mary’s mother subsequently decided to take flight, we might pause for a moment and consider this horrific eyewitness account:

‘Soon after this notable strewing of their footmen’s weapons, began a pitiful sight of the dead corpses lying dispersed abroad, some their legs off, some but houghed, and left lying half-dead, some thrust quite through the body, others the arms cut off, diverse their necks half asunder, many their heads cloven, of sundry the brains pasht out, some others again their heads quite off, with other many kinds of killing. After that and further in chase, all for the most part killed either in the head or in the neck, for our horsemen could not well reach the lower with their swords. And thus with blood and slaughter of the enemy, this chase was continued five miles [eight kilometres] in length westward from the place of their standing, which was in the fallow fields of Inveresk until Edinburgh Park and well nigh to the gates of the town itself and unto Leith, and in breadth nigh 4 miles [6 kilometres], from the Firth sands up toward Dalkeith southward.

In all which space, the dead bodies lay as thick as a man may note cattle grazing in a full replenished pasture. The river ran all red with blood, so that in the same chase were counted, as well by some of our men that somewhat diligently did mark it as by some of them taken prisoners, that very much did lament it, to have been slain about 14 thousand. In all this compass of ground what with weapons, arms, hands, legs, heads, blood and dead bodies, their flight might have been easily tracked to every of their three refuges. And for the smallness of our number and the shortness of the time (which was scant five hours, from one to well nigh six) the mortality was so great, as it was thought, the like aforetime not to have been seen.’

Marie de Guise was at Stirling Castle when she received the news of the defeat, possibly in her Presence Chamber, which you can still visit today in all its sixteenth-century glory. She was deeply afraid for the safety of her daughter and the possibility that English forces might capture her. After all, the English army had reached Edinburgh, only 30 miles or so miles away from Stirling. As a result, it is said that under cover of darkness, little Mary was whisked away from the castle with her mother alongside her. They were headed westwards to Inchmahome Priory.

According to Catherine Vost, ‘Inchmahome was a natural choice, not only because it was an island sanctuary but also because its Commendator, Robert, Master of Erskine, was the son of Mary’s guardian, Lord John Erskine’. Unfortunately for Robert, he had been among the many Scots to die at the battle of Pinkie, but his family connections with the monarchy made Inchmahome the perfect place to retreat to – some 85 miles from the battle site itself.

Life at the Priory

The secluded ruins of Inchmahome still speak of the small scale and intimacy of life at the priory. As might be expected, the little cluster of buildings comprised the main priory church, with its great processional west door at one end and the grand east window at the other. This, of course, once lit the high altar. It can still be admired today.

Cloisters lay to the south, around which conventual buildings were located. Those sited in the east are the most complete and include buildings such as the chapter house (which also still stands and has quite recently been reroofed). According to Historic Environment Scotland, the prior’s lodgings were probably located in the cloister’s west range, at first-floor level, possibly above the cellarer’s stores. However, in a paper on the monasteries of Scotland by Marilyn Guest, she states that ‘The prior’s lodging was over the northern part of the range with the guest house over the southern cellars occupying the part of the range not occupied by the cloister walk’. So, there seems to be disagreement as to the layout of the claustral buildings!

Although nobody knows exactly where Mary and her mother lodged during their three-week stay at Inchmahome Priory, the protocol would dictate that the royal party were housed in the most high-status chambers available; in this case, the prior’s chambers on the west side of the cloister. There, Mary lived amongst the monks of the priory, far away from the chaos of the battlefield and its bloody, bitter aftermath.

According to legend, while staying at Inchmahome Priory, the four-year-old queen began her studies, learning her first Latin, Greek, and Italian while on the island. It is also said that in addition to her formal education, Mary began to learn how to embroider (something that would pass many a long hour later during her interminable imprisonment in England) and tend the gardens of the priory. As Catherine states, ‘It is a testament to her legendary status that various features on the island still bear her name’; these include Queen Mary’s Bower and Queen Mary’s Garden, situated on the southern part of the island. However, they are not thought to be associated directly with her but rather named in honour of a brief moment of time in the already turbulent life of Mary, Queen of Scots.

Leaving Inchmahome Priory

So what happened to Mary after she left Inchmahome? Well, the court returned to Stirling Castle, where Mary would spend one final Christmas with her month in Scotland. Then, in February 1548, the little Queen of Scots travelled to Dumbarton Castle to await transport to France and her destiny as its new dauphine.

Five months later, in July, the Scottish Parliament agreed to her betrothal to Francois, the Dauphin of France. Finally, after adverse winds had delayed departure, the five-year-old Mary and her companions, the ‘Four Maries’, set sail for France. Another chapter in the eventful life of Mary, Queen of Scots, was about to be written.

Visting Inchmahome

Read any account of visiting Inchamhome Priory, and the effusive accounts of the area’s natural beauty will strike you. Unfortunately, time was against me during my recent visit to Scotland, but this location is firmly on my agenda for my next visit. If you want to soak in this place’s tranquillity and spectacular scenery, then check out the website for Historic Environment Scotland, which owns and manages the site.

Under normal circumstances, the priory is accessible between March – October. A 12-person boat shuttles visitors back and forth to the island from the Port of Menteith on the B8034, just off the A81. Boat trips are seasonal, so do check out the website for all the latest.