The 1502 Progress: Coberley Hall, Gloucestershire

Distance from Woodstock: 38 miles

John Felde gromes [grooms] of the Quenes chambre for thaire costes wayting upon the Quenes joyelles [jewels] from Langley to Northlache [Northleach] from Northlache to Coberley from Coberley to the Vineyarde from the Vyneyarde to Flexley Abbey from Flexley Abbey to Troye and from Troye to Ragland by the space of vj dayes…

Privy Purse Expenses of Elizabeth of York, 2 September 1502.

Coberley Hall: Key Facts

– An account of an entry into Elizabeth’s Chamber Books tells us the royal couple stayed at Coberley for one night.

– Coberley Hall was an extensive triple-courtyard manor house, built on the south side of an outer courtyard and the (surviving) parish church.

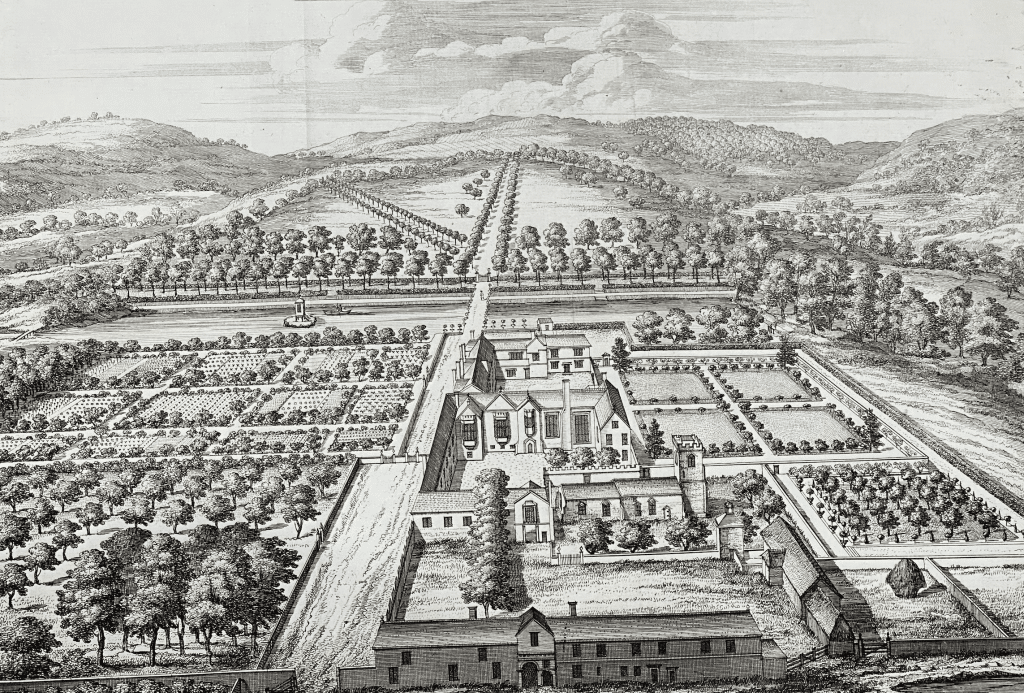

– An engraving by Kipp shows Coberley Hall shortly before its demise in the eighteenth century. The early medieval hall had been incorporated into an expanding complex of buildings whose design mirrored the fashions of the time.

– Sadly, we know nothing about the interiors of the hall.

Just as with Northleach, the only way we know that Elizabeth and Henry travelled through Coberley on the 1502 progress is on account of an entry into Elizabeth’s Chamber Books, recording money paid to the Grooms of the Queen’s Chamber for their part in transporting her jewels from place to place alongside Elizabeth’s household.

Also, like the previous location, it seems likely that the stop at Coberley was just overnight (according to Lisa Ford’s thesis, this was on 10 August), and although no specific building is mentioned, it seems almost unthinkable that the location in question was anywhere other than Coberley Hall. As you will see, the village was small, and the Hall dominated the parish.

The Development of Coberley and Coberley Hall

Even today, Coberley is a tiny village nestled amidst rolling Cotswold hills and green pastures, about ten miles east of Gloucester. According to British History Online, its population never peaked above 367 (recorded in 1911), and in the sixteenth century (1563), there were only 11 households recorded in the parish.

John Leland notes in his Itinerary that Coberley is a contraction of its original name: ‘Cow Berkeley’. As we shall see in a moment, one imagines this links to the name of the family who originally built Coberley’s manor house: The Berkeleys.

Over the centuries, the fate of the village and its parishioners has been inextricably linked to that of its manor house: Coberley Hall (sometimes also known as Coberley Court). The Berkeley family (of Berkeley Castle) had owned the land since 1086, displacing the local Saxon thane who had ruled the area before the Norman invasion. However, it was not until the early thirteenth century that the Berkeleys settled a permanent home in Coberley. Undoubtedly, this brought work and a degree of change and prosperity to the village.

The hall was built on the south side of an outer courtyard and the (surviving) parish church. The latter building was the first substantial place of worship for the villagers, who had hitherto been ministered to by a travelling priest at the site of a Saxon cross. This cross seems to have been located where Roger Berkeley II founded the later church in 1144. According to The Story of Coberley, Gloucestershire by Diana Alexander, ‘All that remains of that first church is a small piece of dog-tooth moulding inserted near the arch from the nave to the side chapel’. The village had to wait another 100 years or so for the manor to spring up beside it.

The engraving above shows Coberley Hall shortly before its demise in the eighteenth century. Undoubtedly, over the centuries, the early medieval hall had been incorporated into an expanding complex of buildings whose design mirrored the fashions of the time. What we see in the engraving is that the house was situated not far north of the River Churn (running across the back of the image). At this point, the river was close to its source, the Seven Springs, which today gives its name to some local buildings and landmarks.

Along the southern side of the gardens, you can see the river crossed by a bridge. This led into an adjacent park, while substantial formal and kitchen gardens can be seen west and east of the hall.

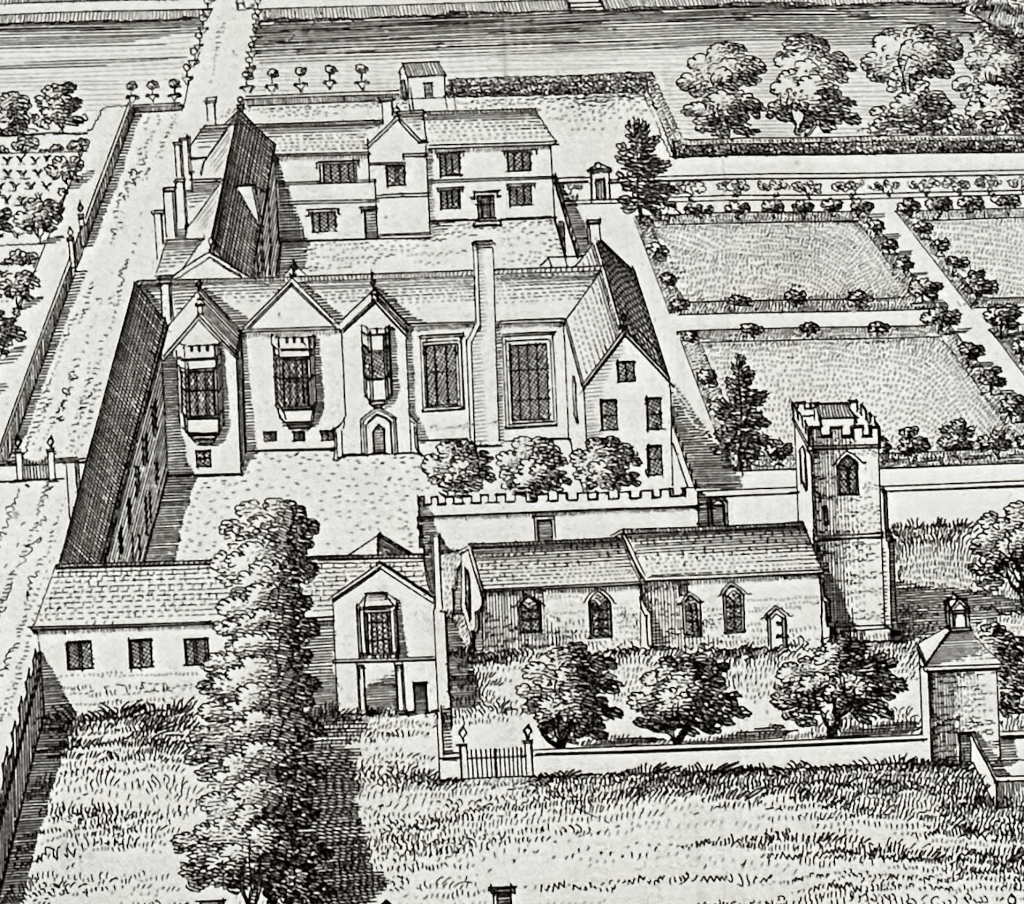

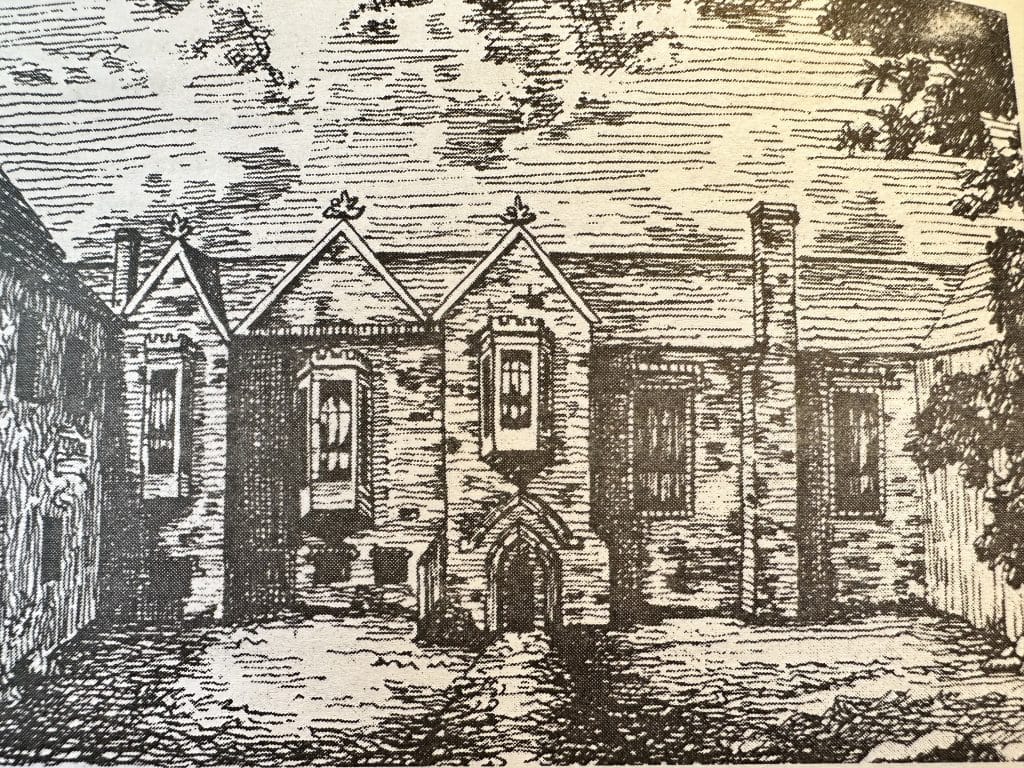

From the same engraving, it is clear that Coberley Hall was an extensive triple courtyard manor house. The north side of the outer courtyard was secured by an outer gatehouse and its associated range (which survives to this day). According to British History Online, this northernmost range also contained a farmhouse and farm buildings.

Directly in line with the outer gateway was an inner gateway leading into the central courtyard. Straight across this second courtyard was the hall’s cross-range. A porch with an oriel window above it no doubt led through to a screen passage and the Great Hall. Two extensive windows can be seen to the right of the porch, while another double-height oriel window lies to its left. Because this is the most decorative of the windows shown in this range, I suspect this led towards the privy lodgings used by the royal couple during their stay at Coberley.

However, I stand to be corrected! I say this because although no east range can be seen on the engraving, this may have already been demolished by the time this engraving was made. Fancy oriel window aside, in some respects, it makes more sense that the privy lodgings lay on the east side of the inner courtyard for two reasons.

Firstly, the two windows to the right of the porch show one smaller and one of full height, lying east of the first window. This full-height window would be typical of one constructed at the high end of a hall to light the dias. It would be usual for the private apartments to be accessed off this end of the hall, suggesting they lay on the east side of the building. The other factor that makes me think there might have been an east wing and that these contained the most high-status lodgings is because such lodgings were often positioned to look out over the formal gardens, the most beautiful of the gardens surrounding the hall. At Coberley, these lay to the east of the house.

Sadly, of the interiors of the hall, we know nothing. Although we might have hoped that Leland would have passed through Coberley on his travels, his only obsession with the places seems to be its source of the River Churn and the Seven Springs mentioned above, which he notes ran through more notable settlements further downstream, such as Cirencester. He also notes that Sir John Brydes has his ‘chief house’ there. Instead, the only note we have about the interiors of Coberley Hall comes from an inventory taken for tax purposes in 1672, when it was noted to have 26 hearths.

While the manor house has gone, we can be thankful that we have Kipp’s engraving that helps us imagine the royal party arriving at the manor towards the end of the first week in August 1502, passing through both gatehouses before dismounting in front of the porch of the cross-range. But who was the host welcoming the arrival of his royal guests? His name was Giles Brydges, the Lord of the Manor of Coberley at the time.

Giles was a son of Thomas Brugge, or Brydges, of Coberley and his wife, Florence Darell. He was born at Coberley Hall in 1462/3. This made him five years younger than King Henry VII. Giles succeeded to his father’s estate in 1493 and, at some point, became Keeper of the Body to Henry VII and Sheriff of Gloucestershire.

Four years after inheriting his patrimony, Giles fought for Henry VII against the Cornish rebels at the Battle of Blackheath (1497) and Exeter against the pretender, Perkin Warbeck (also 1497).

Giles married Isabel Baynham, and together they had seven surviving children John, Thomas, William, Ursula, Florence, Katherine and Anne. Their eldest, John, would carve a notable career at court, being rewarded for his loyalty during the succession crisis by Mary I. She created him 1st Baron Chandos of Sudeley Castle (the famed resting place of Henry VIII’s sixth wife, Katherine Parr) on 8 April 1554.

During the early part of Mary’s reign, Sir John became Lieutenant of the Tower and oversaw the imprisonment of several notable Tudor characters, including Lady Jane Grey (who gave a copy of her English bible to Sir John at her execution), Thomas Wyatt (following the Wyatt Rebellion of 1554), and, for a short time, the queen’s half-sister, Elizabeth Tudor. However, he was accused of being too lenient to the Tudor princess and was removed from his office after only two months of being her custodian.

So much for Sir John. Back to his father, Giles! Having served the Crown faithfully, Gile Brydges died (probably) in December 1511, aged around 49. He was succeeded at Coberley by his son, John. The memorial to Giles and Isabel in St Giles Church at Coberley had, by the beginning of the eighteenth century, been defaced.

Note:

Royal Visits to Coberley Hall:

17 October 1278: Edward I

9 August 1502: Henry VII and Elizabeth of York

August 1535: Henry VIII (and probably Anne Boleyn)

6 November 1643 and 12 July 1644: Charles I

Visitor Information

It would be easy to combine a visit to Coberley with an exploration of the previous stop on the 1502 progress: Northleach – if you have a car as your means of transport.

As mentioned above, Coberley is a tiny village and, therefore, not easy to reach by public transport. The nearest main cities are Gloucester and Cheltenham. A bus that takes about 15 minutes to reach Coberley runs from Cheltenham. Just make sure there is a return bus you can catch that doesn’t leave you stranded in the village for hours, as there is no pub or cafe to take shelter in.

The village lies in an isolated spot. The occasional car will trundle by, but otherwise, you will be surrounded by the sounds of nature as you approach what was once the outer gatehouse and the adjacent range.

You will immediately notice that you are in no ordinary place. A substantial range of stone-built dwellings, woven into what was once the outer perimeter wall, supported by chunky buttresses, make it clear that a building of note once stood here.

As noted above, the church and a piece of wall that once divided the manorial complex from the graveyard still stand. To access these, you must head through the side door adjacent to the great gate. Although you will be crossing private land, this is a public right of way, so be mindful to stick to the path.

As you walk forward, you will see the church in front of you and the gate that leads into the churchyard. The first thing to note is the track that continues ahead to the left of this gate. This would have once been the main thoroughfare passing underneath the inner gatehouse, beyond which lay the second courtyard. Today, a barn and a farmyard occupy this space.

Pass through the gate and walk forward. You will see the original crenulated dividing wall mentioned above. This can be spotted in Kipp’s engraving, separating the second courtyard from the parish church. As you reach the top of the path, you will see the grave of Lombard, the trusty horse whose body is buried nearby.

A little further along, two Elizabethan archways are punched through the wall. The first and largest of these doorways was once the point of access for the family coming to and from the manor to hear services in the church. The second led through to the formal gardens. In fact, at the end of the wall, look out over the open field towards the river (which you cannot see from this point) and imagine the beautiful formal gardens laid out in front of you.

Inside the church, you will be mostly drawn to the chapel on the south side, where some medieval tombs can be found. The chapel was dedicated to the Virgin Mary in 1340. The main effigies are of a Lord and his Lady, Sir Thomas Berkeley, and his wife, Lady Joan. By the way, her son, by her second marriage, was the famous Dick Wittington of pantomime fame, once Lord Mayor of London. While he was not born at Coberley, he spent much of his childhood there. The adjacent small tomb is considered a child of Sir Thomas and Lady Joan.

Finally, don’t forget to look for the unusual heart burial in the corner of the chancel, just to the right of the high altar. Here, the heart of Sir Giles Berkeley, who died in 1295, was laid to rest. Sir Giles had died in Great Malvern but had requested his heart be returned to his home at Coberley.

For Rest and Refreshment: None.

Transport: By car or bus from Cheltenham.

Accommodation: The Wheatsheaf (Northleach); Painswick Lodge, Painswick or Miserden Park

THE NEXT STOP ON YOUR PROGRESS IS ‘THE VINEYARD’, GLOUCESTER.

Other Nearby Tudor Locations of Interest:

Northleach Church (13.4 miles): Northleach was the preceding stop on this progress. As an important Cotswold wool town, there were good reasons why Henry VII made this one of the stops of the 1502 progress. To find out more, read the blog.

St John the Baptist Church, Cirencester (11 miles): Visit this splendid wool church in the wealthy Cotswold town of Cirencester. The church has an opulent porch. Its interior has some glorious early Tudor features, including a chapel where the ceiling looks like a mini-version of the Lady Chapel in Westminster Abbey! (and includes heraldry associated with Henry VII, underlining the King’s close association with the wool merchants of the town). You can hear more about this in my podcast episode with an expert on the Cotswold wool church and Henry VII’s 1502 progress, Samantha Harper. (Coming to this page very soon).

Gloucester (10 miles): Gloucester was a major city during the medieval and Tudor periods. It had five monastic institutions: St OSwold’s Priory, Greyfriars, Blackfriars, Whitefriars, Llanthony Priory and the great St Peter’s Abbey. The latter witnessed the coronation of the young Henry III in 1216 and a visit from Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn in 1535. You may read about the entire 1535 progress in my co-authored book, In the Footsteps of Anne Boleyn, and visit the remains of all of the above. However, the old abbey, now Gloucester Cathedral, should not be missed on account of its glorious architecture, tombs and the finest cloisters in the country.

Painswick (10 miles): Also known as ‘The Queen of the Cotswolds’ because of its beauty. Painswick is a pretty little Cotswold village with a fine church surrounded by 99 yew trees. Legend has it that the devil would destroy the village if the 100th were planted. The churchyard of Saint Mary’s, which houses the yew trees, has been described as “the grandest churchyard in England” by the renowned historian Alec Clifton-Taylor. Also note that the church is the burial place of Sir William Kingston, Anne Boleyn’s goaler, although his tomb was defaced during the Civil War and later hijacked to be reused by another incumbent!

Painswick Lodge is just on the edge of the village, now a B&B, but during the Tudor period, it was the village’s manor house. Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn visited in 1535. For more information, read my blog here.

Miserden (8 miles): This is another tiny Cotswold village, whose manor house was once owned by Sir William Kingston. You can visit the manor’s gardens at various times during the year and walk through the adjacent park. Henry VIII (quite probably with Anne Boleyn) hunted here during the 1535 progress.

Sources:

The Story of Coberley, by Diana Alexander.

A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 7. Originally published by Oxford University Press for Victoria County History, Oxford, 1981.

Coberley: A History of the Chruch and Village, from notes compiled by the late Mrs Eva Atherton.

BRYDGES, Sir John (1492-1557), of Coberley, Glos. The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509-1558, ed. S.T. Bindoff, 1982.

John Leland’s Itinerary: Travels in Tudor England, ed., by John Chandler.

One Comment