Blackfriars: The Very Public Stage for a Right Royal Row

It is a day of seismic importance, 21 June 1529. Many have gathered here alongside you in the Parliament Hall of the Dominican Friary of Blackfriars to witness the very public shaming of a great and dignified queen. It seems that all of London can speak of little else.

An expectant murmur ripples through the gathered crowd; there is a heady blend of tension, mixed with excitement and intense curiosity. The air is thick with gossip as it ebbs and flows like the dangerous currents swirling within the waters of the nearby River Thames. All around you, you catch snippets of rumours being passed like tiny winged messengers between the good and the great of Tudor London.

Above your head, the lofty, vaulted ceiling, with its gloriously painted hammer-beam roof, adds drama to this unprecedented event. Straining over the men sitting directly in front of you, you look towards the high end of the hall. Here, Cardinal Campeggio is ensconced behind a large table, which is covered in rich carpet and arras. Cardinal Wolsey, the king’s first minister, sits to his left, staring impassively ahead, both unmistakable in their scarlet robes of office. To the right of the court, already enthroned upon a chair of cloth of gold, and beneath a large canopy of estate, is the equally unmistakable figure of Henry of England; the man whose scruples over his 20-year marriage to his first wife has led to the convening of this Legatine Court. ‘At some distance beneath the king’ and on the left of the court, Katherine is also seated. She is fighting for her position as the premier lady in the land, for her good name and dignity – and the legitimacy of her only daughter, Mary.

‘The King’s Great Matter’ is reaching its climax. Cardinal Campeggio is the Pope’s representative. He arrived in England on 28 September of the previous year (1528) and, although the Vatican had stalled proceedings for as long as possible, the Legatine Court had finally opened around three weeks earlier, on 31 May 1529. Henry VIII argues that according to Leviticus, he has married his brother’s wife; thus they have sinned against God – an abomination which has left the couple without sons, and the king without a male heir. Unable to live with his tormented conscience, Henry now seeks to end their marriage through the courts, for Katherine has remained implacably opposed to acquiescing to her husband’s demands to quietly step aside and accept that she has lived the last 20 years as little more than the king’s whore!

Suddenly, the clerk of the court calls out above the restless crowd, “King Henry of England, come into the court!”. The king, who is slouched back in his chair, feigns indifference as he flicks his hand in the air, and in a clear voice responds, “Here my Lords!” Despite the bravado, you can detect the thinly veiled tension etched upon Henry’s face.

The clerk calls out a second time, “Katherine, Queen of England, come into the court!” Katherine however, does not reply, instead, she rises from her seat. Gathering her skirts in her hands, she moves swiftly to where the king is seated and falls to her knees, the skirts of her gold and black damask gown billowing out in soft folds across the floor. Impatient of rhetoric, the queen begins to speak plaintively, her thick accent telling of her descent from Spanish shores. She pleads with her husband with such passion that you realise that through the entire speech you hardly seem to draw a single breath.

“Sir, I beseech you for all the loves that hath been between us, and for the love of God, let me have justice and right, take of me some pity and compassion, for I am a poor woman and a stranger born out of your dominion, I have here no assured friend, and much less indifferent counsel: I flee to you as to the head of justice within this realm.” Kneeling at the feet of the king, Katherine reaches out to grasp onto the king’s right hand as she pleads,

“Alas! Sir, wherein have I offended you, or what occasion of displeasure have I designed against your will and pleasure? Intending (as I perceive) to put me from you, I take God and all the world to witness, that I have been to you a true and humble wife, ever conformable to your will and pleasure, that never said or did anything to the contrary thereof, being always well pleased and contented with all things wherein ye had any delight or dalliance, whether it were in little or much, I never grudged in word or countenance, or showed a visage or spark of discontentation. I loved all those whom ye loved only for your sake, whether I had cause or no; and whether they were my friends or my enemies.” For a moment Katherine’s head bows in sorrow, as she pauses, the silence almost suffocating as the crowd that awaits what will follow with bated breath. Katherine raises her head and fixes Henry’s eyes once more.

“This twenty years I have been your true wife or more, and by me ye have had divers children, although it hath pleased God to call them out of this world, which hath been no default in me.

And when ye had me at the first, I take God to be my judge, I was a true maid without touch of man.” The queen paused, shaking her head as if in disbelief of the charges that were being laid against her, before continuing, “And whether it be true or no, I put it to your conscience. If there be any just cause by the law that ye can allege against me, either of dishonesty or any other impediment to banish and put me from you, I am well content to depart, to my great shame and dishonor; and if there be none, then here I most lowly beseech you let me remain in my former estate, and receive justice at your princely hand.

The king, your father, was in the time of his reign of such estimation through the world for his excellent wisdom, that he was accounted and called of all men the second Solomon; and my father Ferdinand, King of Spain, who was esteemed to be one of the wittiest princes that reigned in Spain many years before, were both wise and excellent kings in wisdom and princely behaviour. It is not therefore to be doubted, but that they were elected and gathered as wise counsellors about them as to their high discretions was thought meet.

Also, as me seemeth there was in those days as wise, as well-learned men, and men of good judgement as be present in both realms, who thought then the marriage between you and me good and lawful. Therefore, is it a wonder to me what new inventions are now invented against me, that never intended but honesty. And cause me to stand to the order and judgment of this new court,’ Katherine turns her head briefly, sweeping open her right hand and indicating towards those gathered in the hall, before she forged on, her monologue unbroken by the gesture, “wherein ye may do me much wrong, if ye intend any cruelty; for ye may condemn me for lack of sufficient answer, having no indifferent counsel, but such as be assigned me, with whose wisdom and learning I am not acquainted. Ye must consider that they cannot be indifferent counsellors for my part which be your subjects, and taken out of your own council before, wherein they be made privy, and dare not, for your displeasure, disobey your will and intent, being once made privy thereto.”

With this, the queen turned her head to look over her left shoulder. You are sure she is staring hard at Cardinal Wolsey, whose face you can now see is etched with growing tension, beads of perspiration pricking at the creases on his brow. After a brief moment, she turns once more to plead with her husband in a voice fraught with the agony of injustice, “Therefore, I most humbly require you, in the way of charity, and for the love of God, who is the just judge, to spare the extremity of this new court, until I may be advertised what way and order my friends in Spain will advise me to take. And if ye will not extend to me so much indifferent favour, your pleasure then be fulfilled, and to God I commit my case!”

Clearly irritated by Katherine’s refusal to submit to his will, and that of the Legatine Court, Henry moves to sit forward in his seat, his piggish eyes enflamed with barely concealed rage. It is as if he wishes to speak but cannot find the words to rebuke his wife. There is stunned silence in the hall as Katherine stands, dips a reverential curtsey to the king, before raising herself up to full height; for the briefest of moments, you see a flash of defiance pass like electricity between Katherine and her husband. Snatching at her skirts with her right hand, the queen draws them aside so that she might stride from the court. As she walks away, her back to the king and court, cries ring out from the clerk, imploring Katherine to return to her seat. But to no avail…

As she sweeps by you, you hear the rustle of her skirts, smell the deep, musky scent of her perfume. You stare at her, but in her proud defiance, her eyes are fixed ahead. Not deigning to turn to those who call out her name, her riposte is loud, clear and dismissive, “On, on, it makes no matter, for it is no impartial court for me, therefore I will not tarry. Go on!” Finally, she disappears from sight and the Parliament Hall erupts into chaos behind her…

Tudor Blackfriars: The Stage for a Right Royal Drama

We have all heard of the famous Blackfriars trial in which the king’s case to annul his marriage to Katherine of Aragon was very publicly aired; the queen jousting in an impassioned war of words with the king – a war which she would, tragically for her, lose. But have you ever been curious to know more about this ‘Blackfriars’ and the exact location in which this historic event took place? I know I have, and this time my curiosity has led me back to Tudor London.

The Dominicans were a religious order, nicknamed the ‘Black Friars’ on account of the colour of their black garments. In London, they became the most influential of religious orders with extremely close ties to the Crown. Although their initial base was in an area of London called ‘Holborn’, in the mid-thirteenth century they moved to a part of the City that became known as ‘Blackfriars’ (as it still is today).

But here’s the thing: this was no ordinary move. In order to build the new friary, a good deal of fancy footwork, and careful negotiations, were required between the Dominicans, the Crown and the City of London, because, to accommodate all the friary buildings, not only did many properties have to be demolished but a whole 200-foot long section of London’s city wall needed to be moved westward. No small task!

However, under the initial patronage of Edward I, this is exactly what was accomplished. The rebuilding took place in stages that spanned nearly 40 years. This included reconstructing the west wall of the City out into the Thames as far as the shoreline at low tide, and backfilling it to reclaim an extra 1.75 acres of land. The resulting friary became the most important in London, this is attested to by the great number of wealthy and noble Londoners who were buried, or had monuments erected, in the church. Perhaps the highest status of these was Eleanor of Castille, wife of Edward I, whose heart was buried in the friary church. This patronage was no doubt also helped by the fact that Blackfriars was located in an affluent area of London; indeed Katherine Parr was probably born in the vicinity of the friary.

In terms of position, the compound occupied the most south-westerly corner of the City of London and covered an area of just over 8 acres. Close to Ludgate, Blackfriars was situated at the top of that most fashionable of sixteenth-century streets, The Strand, which connected the City of London with Westminster.

Beyond the western perimeter of Blackfriars precinct was the River Fleet (which today runs along the same course, but underground). By the time the Legatine Court was held at the friary, Bridewell Palace had been built by Henry VIII and was sited just across the other side of the Fleet. To underline the importance of the link between the Crown and Blackfriars, we see a rather unusual arrangement of a bridge-cum-gallery that connected the palace to the friary buildings. Edward Hall describes this gallery as being built especially for the visit of Charles V in 1522, and that ‘it was very long’ and ‘hung with arras’ [tapestries]. This meant that Charles V could be lodged conveniently ‘in great royalty’ within the friary’s guest lodgings, while his retinue was housed in the palace itself.

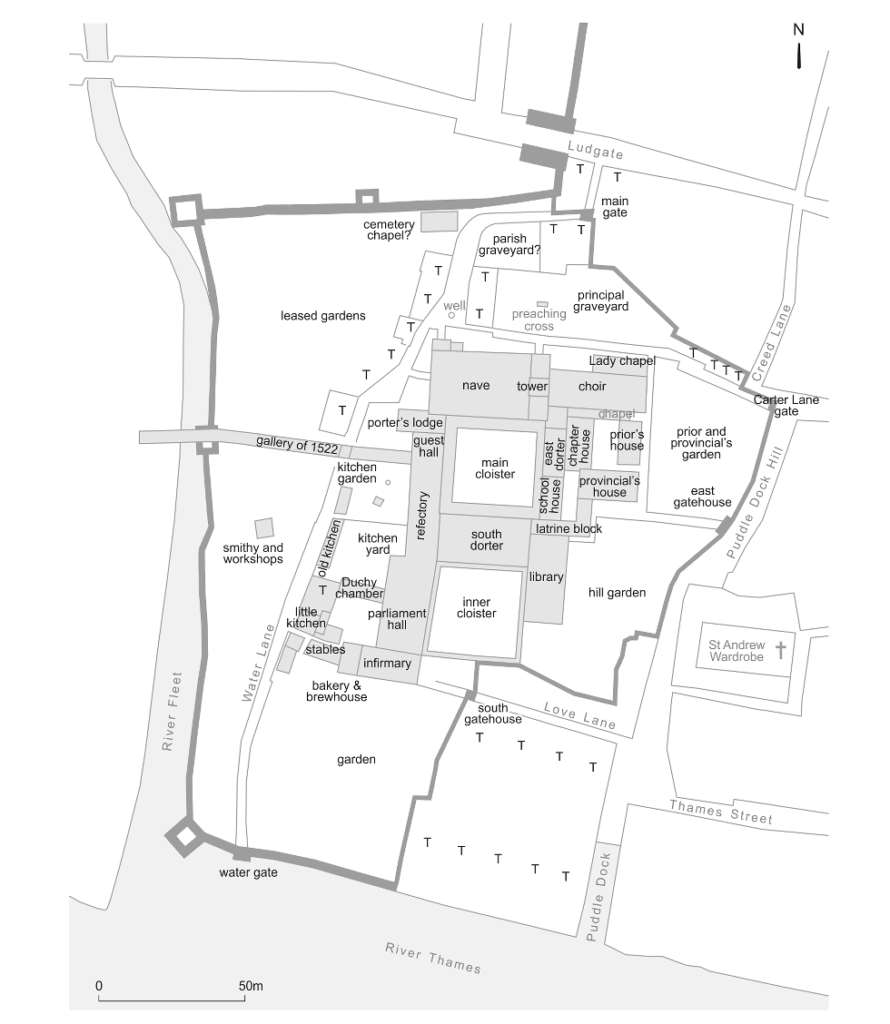

Within the precinct, there was the main friary church to the north, and, as usual, a ‘main cloister’ sited immediately adjacent to the church on its south side. To the east, lay buildings such as the east dorter, chapter house and prior’s lodgings, while to the west were the aforementioned guest lodgings and refectory. Unusually, there was also a second cloister positioned directly to the south of the first, separated from it by the friary’s south dorter.

This ‘inner cloister’ measured approximately 107 feet in length, and was the most private of the two, being the furthest from the point of access to the friary compound. On the east side, opposite the Parliament Hall, was an enormous library; this had the main library room at first-floor level, built over an ‘under library’. The Dominicans were an exceptionally learned order, and the Blackfriars, in particular, were noted as preparing men to go forth and study at the celebrated universities of Oxford, Cambridge or Paris. The collection of books in that building at the time of the Legatine Court must have been quite spectacular: think of its sheer size (two floors, over 107 feet each in length), particularly so given how rare libraries were in the day!

As can clearly be seen on the plan of the friary buildings below, on the west side of the inner cloister was the Parliament Hall: the scene of our royal drama.

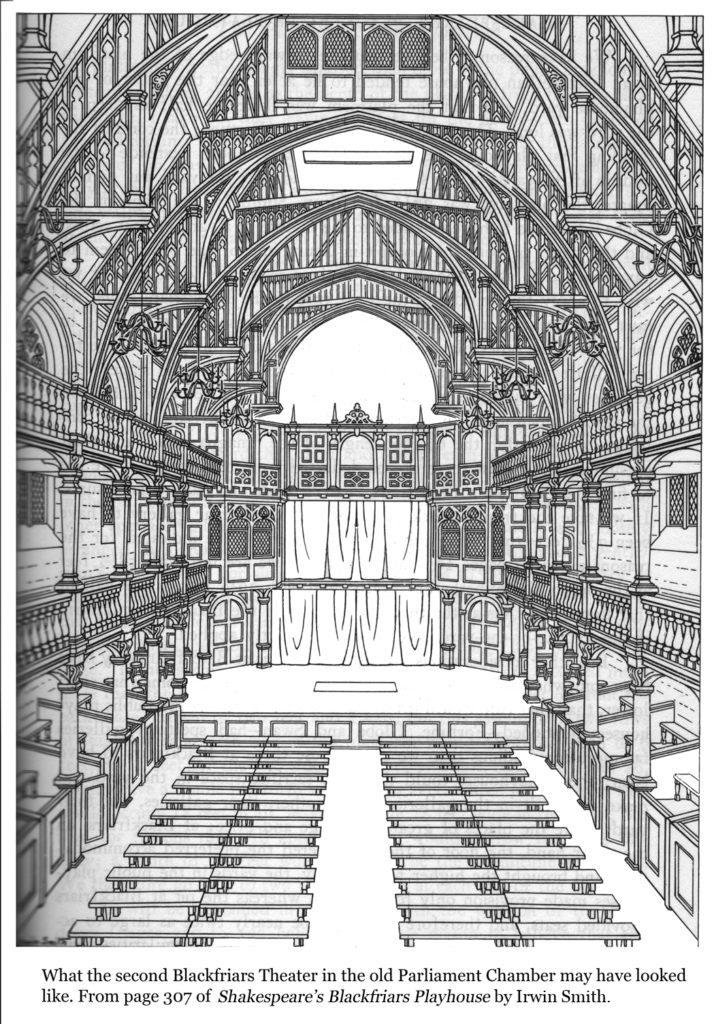

Architecturally, to all intents and purposes, the Parliament Hall was simply a ‘great hall’, but it was given this specific name on account of its peculiar usage during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. In fact, in Edward Hall’s Chronicle, he states that ‘in a great hall, within the Black friars of London, was ordained a solemn place for the two Legates to sit in…’.

Not a great deal is known about the appearance of the Parliament Hall itself. However, we do know something of its scale and construction. The hall ran the entire length of the inner cloister, being 107 feet in length and 52 feet wide. A herald’s drawing in 1524 shows the seating plan for the parliament of that year. According to Nick Holder in The Friaries of Medieval London,’ there is little architectural detail to be seen that can give us any clue as to how the hall appeared at the time, apart from the chequered floor, which Holder states was, ‘perhaps contrasting slabs of dark Purbeck marble [against] paler limestone or sandstone paving’.

However, we can be in no doubt that this was a spectacular stage upon which this right royal drama was enacted. It seems quite apt, therefore, that after the Dissolution of the Monasteries, when Blackfriars was surrendered to the Crown, it was later purchased and renovated to be used as a Shakespearean Playhouse!

We will leave the final words of this sorry tale to Du Bellay, the French Ambassador in London at the time of the Legatine hearing. On 22 June 1529, he wrote to his master, King Francis I, that as far as Katherine’s plight went, ‘If the matter was to be decided by women, he [Henry VIII] would lose the battle; for they did not fail to encourage the Queen at her entrance and departure by their cries, telling her to care for nothing, and other such words; while she recommended herself to their good prayers, and used other Spanish tricks.’ Katherine was not going down without a fight – what is more; the female population of England was on her side!

Visitor Information

Sadly, there are only tiny remnants left of the once-great friary of Blackfriars; a sorry looking fragment of a wall; a blocked up stone window from the late thirteenth-century chapter house (preserved now inside an office block at 10 Friar Street), and a little passage known as ‘Church Entry’, which follows the approximate line of the north-south divide between the nave and the chancel of Blackfriars church. So this one is perhaps only for the die-hard Tudor enthusiast determined to explore an area of London where this once-dominant friary stood witness to this most dramatic of royal dramas.

If you wish to read more about Tudor London, check out our popular blog on Old London Bridge.

Sources

Sources that I have found useful in writing this blog are:

The Friaries of Medieval London by Nick Holder, (Boydell and Brewer)

The Life of Cardinal Wolsey, by Cavendish, George

Edward Hall’s ‘Chronicle‘

2 Comments