The Bishop of London’s Palace & an Audacious Game of Thrones?

When Henry VIII fought openly with his wife at the trial of Blackfriars, he sought to undermine her story that she came to his bed as a virgin. One famous testimony recounted how Arthur had emerged from the couple’s bedchamber in the Bishop of London’s Palace on the morning following their wedding, exclaiming that he was thirsty having ‘spent that night in Spain!’ You may well be familiar with this event, but had you thought about where it actually took place? Having arrived at the Bishop of London’s Palace, following Katherine of Aragon’s reception by the City of London, we will now tag along with events as they unfold, from her marriage in Old St Paul’s to the wedding feast, and finally, the bedding of the couple; what transpired in that room remains controversial to this day!

The Bishop of London’s Palace at Old St Paul’s

In the northwest corner of St Paul’s precinct was the grand palace of the Bishop of London. According to Stow, in his description of 1598, the palace was ‘a large thing for receipt; therein divers kings have been lodged and great households have been kept’. To get our bearings, let us imagine that we have travelled from Westminster, up the fashionable street known as ‘The Strand’, where the likes of Durham House was sited, to cross the River Fleet via Fleet Bridge. In front of you, was the mighty Ludgate, the western entrance to the City of London.

Passing underneath the shadow of this gateway, we continue along a short street, called Ludgate Hill; this climbed upwards towards a second gateway, the Western Gateway, which gave access to the cathedral precinct of Old St Paul’s. Emerging through this second gateway, you are confronted by the magnificent sight of the Gothic cathedral directly ahead of you, with its western facade comprising of the Galilee Porch and flanked to the north and south by two towers, whose function was described in Part 1.

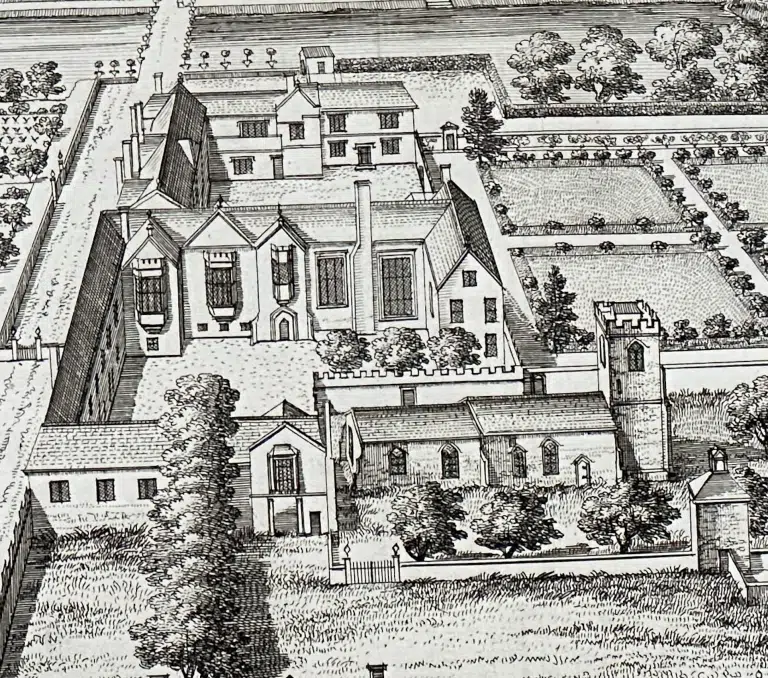

Immediately to your left, occupying the northwest corner of the cathedral grounds, and adjoining the north side of the cathedral itself was the Bishop of London’s Palace. Sadly, there is no comprehensive account of the palace; what it looked like, or how it was laid out. Instead, we have to snatch tiny fragments of information from various contemporary documents and piece them together to give us a picture of the palace’s appearance. However, helpfully, Herbert Cox and H.W. Brewer provide a plan in their book on Old London Illustrated, (see below). Although the sources used for such an accurate depiction are not given, it does help us broadly to understand more about the position of the palace which lodged first Katherine, then the newlyweds, for those few joyous days in November 1501.

The plan shows that the Bishop of London’s palace was accessed from the ‘west church yard’ by a Great Gateway. We know that the building comprised two chapels, the upper and lower; the lower one probably being in the crypt, underneath the upper. There was a great hall and ‘great chamber’ – in which much jovial celebration around the nuptials took place – at least one ‘chamber containing the state bed’ (cited as part of the description of the Katherine and Arthur’s wedding night, which we shall come to in a moment). We hear also hear of Katherine keeping herself in her ‘secret chamber’ the day after the wedding, accompanied only by her closest ladies and gentlewomen, and also an ‘outer gallery’ which seems to have given private access to the body of the cathedral.

Perhaps a more grim side to the episcopal palace was that, in line with other similar residences, like Lambeth Palace, there were two prisons: The Coal House, mentioned by John Foxe in his Acts and Monuments, and the Salt House. In describing the plight of heretics brought to the palace for interrogation, we hear of some of the other chambers in the palace: the wardrobe; the gallery; the upper hall and chapel; these were rooms in which the suspected heretics were interrogated by the bishop and other prelates. It must have been a terrifying experience! Of course, there were undoubtedly many more chambers in the palace, consistent with any high-status property of the day, but these are the ones specifically mentioned in various accounts. However, let’s not rush ahead of ourselves. There are other events to relish first before we return to the palace!

Having rested overnight at the Bishop of London’s Palace, the next day, at about 3 or 4 o’clock in the afternoon, Katherine was conducted from the palace, out of the cathedral precinct via the southern gateway, along St Paul’s Chain and directly south to Baynard’s Castle, there to have her first audience with the queen, Elizabeth of York. The Spanish Princess was conveyed in a litter ‘apparelled most costly both within and without’ and was ‘received and accepted by the Queen’s grace, and with pleasure and goodly communication, dancing and disportes’. The king who had, at the same time, been receiving a Spanish delegation of the great and the good, joined the party at some point. This went on until late in the evening, until, by flickering torchlight, Katherine was conveyed back to the Bishop of London’s Palace. The ‘morrow was her big day!

The Bishop of London’s Palace : The Nuptial Lodgings

Old St Paul’s Cathedral was the largest church in England and, interestingly, the only one with cloisters on both its north and south sides. In preparation for the wedding of Arthur and Katherine, ‘bowers’ had been hung from the Great Gate of the Bishop’s Palace to the west door of St Paul’s. Inside ‘costly and rich cloth of arras’ (tapestry) had been hung along the body of the church, so high that ‘the lowest part thereof be seven or eight feet from the ground’, while a huge elevated platform had been constructed from the west doors to the choir – in all, a distance of about 600-700 feet. The platform is described as being about 4 feet high and 12 feet wide, with rails on either side. The entire length was covered with red worsted that had been nailed in place with gilt nails. At the far end, a round platform provided the place in which the wedding ceremony would actually take place.

Near to this platform above ‘where the court and consistory (ecclesiastical court) used to be kept… there was a closet made properly with lattice windows enclosed, within which closet the King’s Grace and the Queen’s might stand secretly’ to watch the ceremony take place. A doorway leading directly from the Bishop’s Palace had been specially constructed so that the king and queen might pass directly through into their closet in private.

From the King’s Wardrobe [Baynard’s Castle], the groom set out at about 9 or 10 o’clock in the morning. He probably took the route which Katherine had taken the night before, entering the southern precinct of the cathedral, before dismounting at the south door and making his humble devotions before God. Arthur needed to change his clothing into ‘royal and comfortable apparel of wedding and spousage’. The chronicler of The Receyt reports how he slipped into the Bishop of London’s Palace, where Katherine was no doubt giddily putting the finishing touches to her own wedding garments. Both were to be dressed in dazzling white satin and, although we hear very little specifically about it, one imagines dripping with costly jewels. In line with tradition, the Prince of Wales then went back to the church to await his auburn-haired, Spanish bride.

Meanwhile, Katherine was received at the west doors of Old St Paul’s, accompanied by a great number of ‘lords, knights, gentlemen and ladies, and other gentlewomen’. She was led into the church by Henry, Duke of York and the ‘earl that came with her out of Spain’. The English chronicler who recorded the event was clearly bemused by Katherine’s dress, which he describes as a ‘strange diversity of dressing of the country of Spain’. Her gown was ‘very large, both the sleeves and the body, with many pleats, such like men’s clothing’, and he noted that all the Spanish ladies were wearing ’round hoops, bearing out their gowns from their bodies’. Here, we have the first mention of the Spanish farthingale in England, and the reason that Katherine is often cited as being responsible for the garment becoming fashionable on English shores! Finally, upon her head, Katherine wore a coif of white silk with a border of gold, pearl and precious stones.

The couple were married in front of the choir, at the end of the nave, upon the raised platform already described. The ceremony complete, the ‘minstrels – both trumpets, shalmewes and sakbottes – struck up and made such melodies and mirth as they could’. Meanwhile, the couple took each other by the hand, Arthur on Katherine’s right side, turning to the south and the north, so that all might see their faces. This done, the newlyweds processed deeper into the church, to the high altar, where the couple heard High Mass below the magnificent rose window at the east end of the cathedral, all accompanied by song and music.

Then, with the service over, the Prince and Princess of Wales, led once more by Prince Henry and the ‘Earl from Spain’, made their way back through the church to the west doors. Outside, in the western churchyard, a pageant had been running through the ceremony and wine followed freely from a nearby conduit, no doubt much to the great pleasure of the gathered crowds. The pageant consisted of a ‘great mountain’ covered in green grass, herbs and precious mineral ores. Atop the mountain were three great trees with the three kings of France, England and Spain each standing in the ‘middle’ of a white hart, a ship and a castle respectively, with their escutcheons and arms above their heads. Quite what the intended meaning of the pageant was has been lost on a twenty-first-century woman like me, but no doubt it conveyed deep significance to those observing it at the time.

The procession passed the pageant and returned to the bishop’s palace, where the wedding breakfast, as we would call it today, took place in two of the largest chambers: the great hall and ‘great chamber’ (probably the great watching chamber of the palace). The Prince and Princess dined in the latter, along with others ‘of great reputation’, whilst the lower order guests ate in the hall. Each room was ‘most pleasantly and stately dressed’ with ‘hangings of royalty and every accoutrement that might belong to so noble estate’, including a cupboard displaying plate of gold, which was described as being ‘very precious and rich’, in the great chamber, and a similar one with plate of sliver-gilt in the hall.

We hear nothing more of the feasting except that what was served included the ‘most delicate, dainty and curious “metes” that might be purveyed or gotten within the whole realm of England’. The feasting, dancing and goodly disport went on until 4 or 5 o’clock in the afternoon. Thereafter, great persons of noble birth prepared both the chamber and bed in which the newlyweds would spend their first night together. This seems to have taken some time ‘2 or 3 hours’ after which the Earl of Oxford, as great Chamberlain of England, inspected the room. And so, at perhaps 7 or 8 o’clock in the evening, with a darkness long fallen outside the window, the Spanish Princess was put to bed, to be joined shortly thereafter by Arthur, who was accompanied by ‘His Grace’ (the king, one assumes) and other nobles. The bed was blessed – and thus ‘these worthy persons concluded and consummated…the sacrament of matrimony’.

Of course, the issue of whether Arthur and Katherine ever did consummate their marriage became a subject of intense debate and contention some 30 years later. Henry VIII, now Katherine’s husband, (following his brother Arthur’s death just months after the marriage), was without an heir. He was desperate to divorce Katherine on the grounds that he had taken his brother’s wife; according to Leviticus, this was sinful and meant that the couple would never be able to bear a healthy son – in effect, the marriage was cursed. Katherine maintained till her dying day that it was never so and that she came to Henry’s bed a virgin. Was she playing an audacious game of thrones, determined to hang onto her position as queen at all costs? It was certainly a claim that she was prepared to make in open court, doing so during the Blackfriars’ trial in 1528, (a building that was itself just a stone’s throw from the Bishop’s Palace, where the ill-fated couple had spent their first night together!)

However, those speaking against the queen insisted that she was lying – or at cast serious doubt on the veracity of her claim. One such person to testify was Sir Anthony Willoughby, who stated in court that the morning following his wedding Arthur had emerged from Katherine’s bedchamber to say, “Willoughby, bring me a cup of ale, for I have been this night in the midst of Spain!” Now, my aim here is not to debate the question of ‘did they or didn’t they’, but to pinpoint the location in which this famous phrase was uttered: the Bishop of London’s Palace, adjacent to Old St Paul’s Cathedral.

And so the celebrations continued for much of the rest of the week; at Margaret Beaufort’s residence, Coldharbour Palace in the City; at Baynard’s Castle with the king and queen as hosts, and at Westminster, until the king finally removed to Richmond Palace on the Friday. But here, we will take our leave, remembering that whilst all these celebrations took place, many miles away in a cradle in Norfolk, a small child, probably just months old, lay gurgling her innocent delight. She would be Katherine’s nemesis, and Katherine would be hers: her name was Anne Boleyn.

And so it begins…

Footnote:

By the late 16th century, the Bishop of London’s palace was falling into decay; the bishop had relocated to Aldersgate Street, and as the palace was no longer used as an episcopal residence, it was turned into tenements. The building was ultimately destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666, along with the adjoining cathedral. What remained of the palace that had welcomed kings, queens, princes and ambassadors alike lay in ruins.

Notes:

Sources I have found particularly useful in writing this article are:

The Receyt of the Ladie Kateryne, by Unknown

Annals of St. Paul’s Cathedral, by Henry Hart Milman

Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archæological Society, by London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, Middlesex Local History Council

3 Comments