Anne Boleyn’s Coronation Procession

Following Anne Boleyn’s coronation procession, on Whitsunday, 1 June 1533, my Lady Marquess of Pembroke was finally crowned Queen of England. It came about as the result of a historic love that had torn the court, and the country, apart. The aftershock would not only profoundly impact people’s lives but that of the nation as a whole. Were the couple even remotely aware of the ramifications of their intense relationship as the Crown of St Edward the Confessor was placed upon Anne’s head, or was this first and foremost a personal triumph of their desire over those who had fought tooth and nail to rid the king of Anne Boleyn?

As part of this year’s All Things Boleyn series on the Talking Tudors podcast, I chatted to the show’s host and my long-time Tudor friend, Natalie Gruneninger, about Anne Boleyn’s journey from Greenwich Palace to Westminster ahead of her coronation on Whitsunday 1 June 1533. In the following, which has been adapted from that discussion, I touch on the long and winding road leading up to this triumphant moment, alighting on key milestones along the way, before talking in more detail about Anne Boleyn’s coronation procession itself and the traditional festivities held at the Tower to mark this momentous event.

The Long and Winding Road to the Crown…

The celebrations surrounding Anne Boleyn’s coronation began on 29 May, when the summer queen processed amidst an enormous flotilla of barges up the Thames towards her first stop en route to Westminster. This first stop was the Tower of London, adjacent to the City of London. It was the tradition that the monarch would stay at the Tower before processing through the City, down the Strand (then the main thoroughfare linking the city with the royal enclave of Westminster) to reach Westminster Hall ahead of the following day’s coronation.

Anne lodged at the tower over two days from her arrival on 29 May to her departure on 31 May. During her stay, there was feasting and the ceremonial creation of new ‘Knights of the Bath’, all part of the traditional coronation festivities. But, of course, there had been a long and winding road to reach this point. To put this momentous occasion in perspective, let’s remind ourselves how trying that journey had been for the royal couple.

There is debate about when the romance between Anne and Henry began. Historians have different perspectives on the matter. David Starkey believes that Anne had surrendered herself to the king at some point just before Christmas / New Year of 1526/7. He cites that the word ‘etrenne’ (found in one of Henry VIII’s love letters to Anne) refers specifically to a ‘New Year’s gift’. This gift from Anne to Henry was a jewel of a damsel aboard a ship being tossed on a stormy sea. It signified her surrender, body and soul, into the king’s hands.

The late Prof Eric Ives on the other hand, states that definitive proof of their involvement first comes in the summer of 1527. In June 1527, Henry had made it clear to Katherine of Aragon that he meant to appeal to Rome for a divorce. This he does in August of that year.

Ives believes that the exact wording of the appeal to Rome, in which Henry requests a dispensation, indicates that by this time, the couple had agreed to marry: (NB: a dispensation covered a woman who was related to the king by the first degree of affinity: in this instance, this referred to Mary Carey, Anne sister, who had previously been the mistress of the king).

As we know from one of Henry’s letters to Anne, the king had been ‘struck by the dart of love’ for over a year when he penned that particular note. According to Ives, this puts us in the middle of 1526 for the first hint of any romantic involvement between the couple. There is perhaps more evidence of this. At Shrovetide (February) 1526, Henry made an enigmatic declaration on the tiltyard when he boldly wore the motto ‘declare I dare not’. Did this refer to his growing interest in Anne Boleyn?

The dating of the initiation of the relationship is relevant. As Ives argues, if the date of 1526 is correct, then Anne becomes the catalyst ‘pushing’ Henry towards discarding his first wife. If we consider the latter date correct (Christmas / New Year 1526/27), Anne only agrees to pursue the relationship after Henry’s intention to divorce Katherine is made clear. According to Ives, in the latter scenario, Anne merely becomes an ‘accomplice to fornication’.

Unfortunately, we do not have a definitive answer to when Henry and Anne’s first dalliance ignited into a powder keg of passion. However, we can safely say that the relationship was well-established during the second half of 1527.

Of course, what followed was not the quick resolution the king hoped for. As it became known, the King’s Great Matter would drag on for six years; Katherine would not go quietly to the ‘scandal of Christendom’ as she referred to Anne. The Pope, who might have quickly granted a divorce under normal circumstances, was effectively held prisoner by Katherine’s nephew, Charles V. Understandably, he dared not offend the Holy Roman Emperor and subsequently prevaricated over the decision to within an inch of his life!

People died as a result; Wolsey was an indirect but likely victim of the intense stress he was placed under. Sir Thomas More and Bishop Fisher went to the block for their effective intransigence as Henry attempted to wrestle control off Rome and decide the matter for himself in England. Ultimately, of course, the Pope’s inability to resolve the divorce question from Katherine of Aragon to the king’s pleasure would herald the effective end of the dominance of the Roman Catholic Church in England. However, all this was yet to come.

The next major milestone on Anne’s journey towards the Crown was her elevation to the title of Marquess of Pembroke. At this point, after dragging on with not much to show for their efforts, events began to move apace. After five years or so of waiting, the next 10 months would finally see the couple achieve all that they had strived for. On 1 September 1532, Anne was raised to the peerage. As Marquess, it would be an honour she would hold in her own right, quite unprecedented for a woman of that time. Again, the timing is significant. The couple were due to travel to Calais the following month. To position Anne as the King’s queen-in-waiting, Anne needed an aristocratic title.

The trip to Calais was a momentous one for Anne. The newly created ‘Lady Marquess’ was not only warmly received by Francis (although the ladies of the French court declined to be present), it is believed that at some point during their stay in the town, the couple slept together for the first time. It did not take Anne long to conceive.

By Christmas of the same year, Anne probably realised she was pregnant. This, in all likelihood, accelerated Henry’s plans. It resulted in their likely marriage on 25 January 1533, in a secret pre-dawn ceremony held in one of the upper chambers of the Holbein Gate, part of Whitehall Palace. (Of course, some people believe they had already been married on St Erkenwald’s day, 14th November 1532, the day they arrived back from Calais, as recorded by Edward Hall, the chronicler).

Just three months later, in April 1533, Henry VIII’s Act of Succession was passed. This named Anne regent for any child the couple should have together and who might still be in his / her minority in the event of the king’s untimely death. It was a huge honour and would have effectively left Anne as the ruling Queen of England until her child reached his majority.

Anne Boleyn’s Coronation Procession.

Anne Boleyn’s coronation was set for Whitsunday, 1 June 1533. However, one tiny point of irritation still needed to be dealt with. As Eustace Chapuys so bluntly pointed out, the king was technically a bigamist; he was still married to Katherine of Aragon. However, Henry was now all-powerful in matters of ecclesiastic jurisdiction in the realm and now never believed that he had been married to Katherine. Days before Anne’s coronation, a court was convened at Dunstable, led by Thomas Cranmer, the new pro-Boleyn, pro-reformist Archbishop of Canterbury. Unsurprisingly, Katherine of Aragon’s marriage to Henry was declared null and void in the absence of the ‘queen’. She was nearby, exiled from the court at Ampthill but refused to attend the hearing that declared on her marriage.

Meanwhile, some 50 or so miles away at Greenwich, Anne was preparing for her big day. After the long, drawn-out years of waiting, Anne’s coronation was a considerable triumph for the couple. Eric Ives states it was the first ‘major exhibition of civic pageantry since 1522 (when Charles V made his entry into London), and only the second of its kind in the whole reign’.

Of course, an event of this size and significance required a good deal of preparation – and in this case, there was a relatively short period of time to get everything ready. Anne would already be six months pregnant by the time she was crowned on 1 June. Henry wanted his son born to an anointed queen; there could be no question of legitimacy, and so the race was on; there was no time to lose.

While there would have been protocol to help guide what needed to happen and in what order during the coronation ceremony itself, there was still the question of ensuring everyone was in the right place, at the right time, appropriately attired and that the physical ‘props’ of the theatre of coronation were in place.

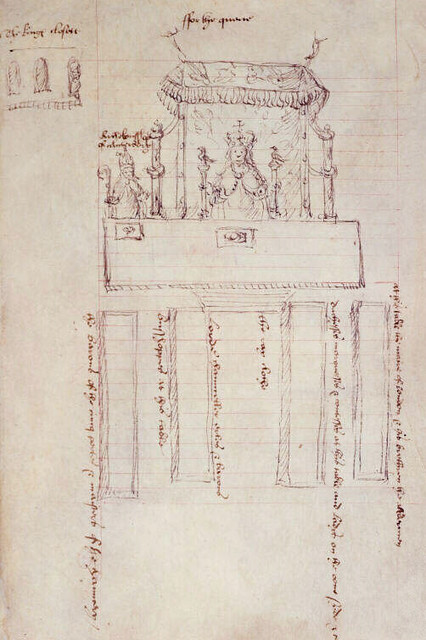

Notably, this meant completing the new queen’s apartments at the Tower, preparing the streets and buildings along the coronation route (which we will hear more of shortly) and designing the pageants to celebrate the new queen as she passed from the Tower to Westminster. Nicolas Udall and John Leyland were drafted to write verses in the queen’s honour, while that genius of the sixteenth century, Hans Holbein, was tasked with designing the physical appearance of the ‘sets’ upon which the plays and verses would be enacted.

In Westminster Abbey, viewing galleries needed to be erected so that people could adequately see the ceremony and the Great Hall at the Old Palace of Westminster needed to be prepared for the coronation feast. This included the construction of a high platform and canopy of estate under which Anne would dine following the ceremony. Workmen were no doubt working through the night – and probably by candlelight – in order to get everything ready in time.

No doubt a flurry of invitations was sent across the length and breadth of the realm; the aristocracy and prelates of the land would have been dusting off their ceremonial robes or perhaps having new garments made especially for the event.

The pageantry of Anne’s coronation was spread out over four days. On the first day, Anne was escorted by river from Greenwich Palace to the Tower of London, where several courtly rituals took place over 48 hours. Here, Anne Boleyn lodged in the newly expanded and refurbished royal apartments, which Thomas Cromwell had been entrusted with ensuring was completed on time.

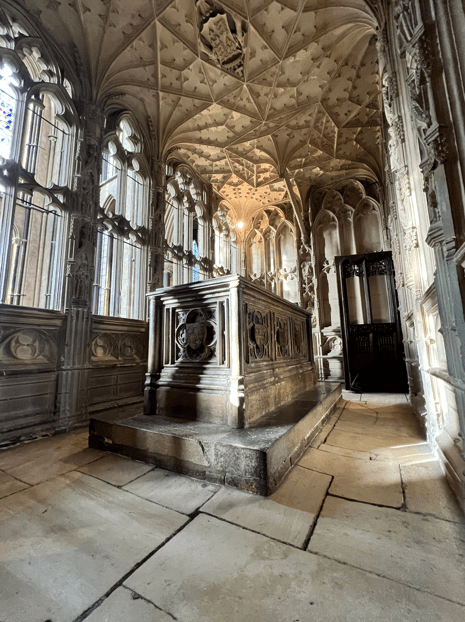

The Tower, like many early medieval castles, had been constructed with an outer and inner ward. The inner ward contained the most high-status apartments, in this case, the domain of the king and queen. There was a thirteenth-century great hall which led to the king’s lodgings. Off the King’s lodgings were the refurbished queen’s apartments.

This suite of lodgings consisted of a series of chambers overlooking the inner ward on one side and the privy gardens on the other. Unusually, the rooms on the queen’s side were more extensive than the kings – almost unheard of elsewhere. But of course, this reflected the fact that the rooms had been specifically built to house the festivities surrounding Anne’s coronation, including a feast that followed the creation of several Knights of the Bath.

This ancient ceremony was incorporated into the festivities running up to the actual coronation itself. It took place at the Tower the day after Anne’s arrival, on Friday, 30 May 1533, extending through the night into the following day, 31 May.

The Order of the Knights of the Bath is the second most noble and important order of chivalry after the Knights of the Garter. The creation of new knights was a ritual often associated with the coronation of a new monarch. It certainly was an honour to be chosen. In advance of Anne’s coronation, 18 new knights were to be dubbed by the king. One of these was, incidentally, Sir Francis Weston, who would later die alongside Anne, and four other men, during the downfall of the Boleyns.

The ceremony began the day after Anne arrived at the Tower, on Friday, 30 May 1533 and continued overnight into the following day, 31 May. Edward Hall, the chronicler, describes that initially, dinner was served with all the knights-to-be present as guests. Afterwards, these men were led to their chambers in the White Tower, where they were ceremonially bathed.

An old account of the ceremony from the time of Henry IV’s coronation, 140 years earlier, describes the ceremony, which we might assume had changed little over the intervening period. Traditionally, the king entered one of the chambers in the White Tower in procession. Each knight was already in their bath. The monarch then inducted each knight by turn with words about the vows they were to uphold, dipping his fingers in the water and making a sign of a cross upon their naked back. Afterwards, the knights were dried and dressed before resting in a nearby bed.

At some point, the knights-to-be were summoned by a curfew bell. Attendants would dress them as monks, and the men would process to the ancient chapel of St John, where their new armour and insignia awaited them. There, the knights would keep vigil, near the high altar, for the rest of the night. In the morning, they would emerge as new Knights of the Bath.

After mass, held at 8 am, the new Knights of the Bath were received in the Great Hall in their golden spurs and gilded belts to be dubbed by the king. Before Anne Boleyn’s coronation, a further 48 Knights Batchelor were also created. After all this was done, the court assembled for a celebratory dinner in the queen’s apartments before Anne made ready for her entry into the City of London.

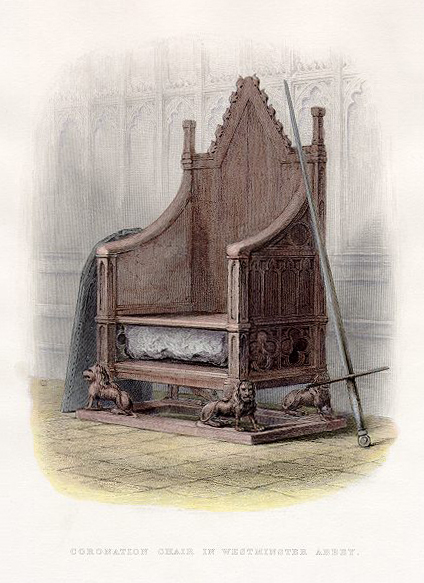

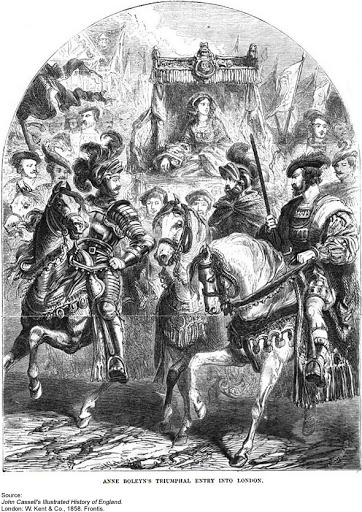

On Saturday, 31 May 1533, the procession that would escort Anne Boleyn from the Tower to Westminster assembled, one assumes, in the outer ward of the Tower. Anne wore a white cloth of gold gown, a coif made of white silk in the French style ‘cross barred with gold cord and edged with passement’. A coronet was placed over the coif. (Except the Crown of St Edward the Confessor, the coronets worn by Anne had been specially commissioned and made for her).

Anne Boleyn’s coronation procession was an enormous 2.5 miles long! The queen’s litter was wheelless, carried via harnesses by white horses. It was furnished in white satin and white cloth of gold. So, we might imagine Anne shining brightly in white and shimmering gold. No doubt this was the desired effect, specifically chosen so that she literally stood out from the rich, dark colours worn by others in the procession.

It is recorded that 400 gentlemen preceded her, walking in pairs. Notable amongst these were the men of the French Ambassador’s household, affirming Anne’s affinity with France. The Gentlemen of the King’s Privy Household came next; nine judges in scarlet velvet followed, and then came the newly created Knights of the Bath in scarlet robes with hoods of miniver. High-ranking church men were followed by marquesses, earls and barons, all mounted on horseback. The Archbishop of York accompanied the Venetian Ambassador, while Thomas Cranmer, as Archbishop of Canterbury, rode alongside the French Ambassador.

Then came the focus of all attention; the group that processed just in front of Anne. The Mayor of the City of London, Christopher Ascue, took these honourable positions, carrying the ceremonial mace (a symbol of protection of the queen). Then, in front of Anne: 23-year-old Lord William Howard, Anne’s Uncle. William was standing in for Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk and Earl Marshal of England, who was away in France (as was George Boleyn) on a diplomatic mission for the king. Riding beside him was Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, as High Constable.

Anne herself came next. She was seated in her litter beneath a cloth of gold canopy, which was carried by the Four Wardens of the Cinque Ports, while behind them came Lord Burgh, Anne’s Lord Chamberlain and seven of the most high-status ladies in the land.

Then came two litters that carried more aristocratic ladies, including Anne’s step-grandmother, the 56-year-old Agnes, Dower Duchess of Norfolk and 47-year-old Margaret, Dowager Duchess of Dorset. More chariots followed; one was furnished with white cloth and the other red. Each contained yet more ladies, while a train of around 30 women dressed in velvet and silk followed. At the tail end of the procession came the Master of the Guard and attendant constables, all wearing velvet and damask coats.

Perhaps we should take a moment to note who wasn’t there. I have already mentioned the Duke of Norfolk, Anne’s uncle, as well as her brother, George. Being so close to George, Anne must have felt his absence sorely. However, the absence of Henry VIII’s sister, Mary was more pointed. It is unlikely that Mary would have demeaned herself by attending and paying homage to Anne, who she clearly disliked. However, Mary’s haughty pride aside, by this time, the dowager Queen of France was terminally ill and lay dying at the Suffok’s country seat of Westhorpe Hall. Mary Tudor would die there just three-and-a-half weeks later, on 24 June.

As Anne Boleyn’s coronation procession passed through the streets of London, her reception seemed to have been mixed. In many people’s eyes, Anne Boleyn had displaced the person many saw as Henry’s rightful queen: Katherine of Aragon. Women, in particular, felt threatened by this turn of events. For if the king could cast aside his wife of over 20 years, his anointed queen, what might that mean for the security of their marriages? No doubt some people liked her and enjoyed being swept up in the colour and pageantry of the event. However, Anne complained to Henry that she had seen many caps upon people’s heads – clearly a sign of disrespect. Anne Boleyn was never to be the people’s queen.

As previously mentioned, the whole route had been prepared in advance; the roads swept and gritted ‘against the queen’s coming’. The buildings that lined the city’s cramped streets, many of which were three or even four stories high, were decorated with arras, carpets, cloth of gold and silver and other rich fabrics. The Eleanor Cross in Cheapside – the main thoroughfare through the city had been repainted and hung with coats of arms.

The streets would have been packed. The painting of the coronation procession of Edward VI shows the king making his way down Cheapside and gives us a good idea of how it would have looked on that May morning. Whether people were pro or against the new queen, curiosity indeed brought them out onto the streets, hanging out of windows or perched on rooftops overlooking the procession. No doubt everyone was interested in getting a glimpse of Henry’s new wife and queen…and if not that, then chance to enjoy some of the wine that, as custom dictated, flowed freely from conduits sited along the route.

Tradition pageants were also staged along the way. This was typical of great ceremonial Tudor events. Something similar, for example, had been arranged for Katherine of Aragon’s entry into the City when she had come to marry Arthur Tudor in 1501.

Fertility, and the importance of the queen in propagating the royal line, always featured heavily. However, one of my favourite pageants was the one staged outside the old Gothic St Pauls’, where a virgin dressed in white and holding a gold tablet in her hands had upon it written the phrase: ‘veni amica coronaberis’ – ‘come my love thy shalt be crowned’. To me, it is as if Henry is talking directly to Anne in the most intimate way amid a great public spectacle, speaking of the great love which had brought the two to this point.

From there, Anne Boleyn’s coronation procession left the City via Ludgate. The route would take her down the Strand to reach Charing Cross (where the royal stables of Whitehall Palace were sited), before turning down King Street and heading southward, passing the Palace of Whitehall, under the Holbein Gate and on to Westminster. Here, Anne was received in Westminster Hall.

Anne Boleyn’s coronation procession was complete. With that, she slipped out of the back of the Old Palace of Westminster to take a barge downstream, just half a mile away to the Palace of Whitehall, to reunite with Henry and contemplate all that lay ahead. The next day would be a truly historic day; it was the day that Anne Boleyn would finally be crowned Queen of England.

If you’d now like to listen to me in conversation with Natalie in her ‘Talking Tudors’ podcast, follow this link.

Sources:

There are primary sources which record this momentous event. There is a surviving copy of a pamphlet produced at the time of Anne Boleyn’s coronation by Wynkin de Worde called: The Noble Tryumphaunt Coronacyon of Quene Anne – Wyfe unto the Noble Kynge Henry the VIII. The original is in the British Library.

Another source from the sixteenth century but written after the event is Edward Hall’s Chronicle, which you can view online here.

I just love your detail and some of the images I haven’t seen before and they just bring the whole story to life! I’ve long struggled with the relationship between Anne and Mary Boleyn – of course my mind is permeated by fictional accounts, but what, if anything, do we know about where Mary was during Anne’s coronation? I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again – THANK YOU for all the detail and your passion! I know that during this time of being furloughed from my job as a Children’s Librarian – I would be stuck in the 14, 15, 16th C. if my husband wasn’t here to pull me out occasionally!!!

LOL! Funny! Thanks so so much for reading the article and enjoying it. That makes my day!

Excellent write-up. I will set this article as a wider reading task for A-level students. It helps bring to life this period of history.