Leicester Abbey: The Mystery of the Lost Tomb of Cardinal Wolsey

Thomas Wolsey was a lucky man. Accused of treason, he narrowly avoided Henry VIII’s ‘justice’ on the scaffold and instead died of natural causes at Leicester Abbey on 29 November 1530. Earlier that month, Henry VIII’s once all-powerful minister had been arrested on charges of high treason at his archepiscopal palace of Cawood, near York. But on his way south, the Cardinal was taken gravely ill at Sheffield Manor, home of the 4th Earl of Shrewsbury, George Talbot. The symptoms were vividly recorded in an account of Wolsey’s life by his Gentleman Usher, George Cavendish.

From the outset of his symptoms, both men knew that he was in mortal danger. Yet, just what did happen to Thomas Wolsey? What do these symptoms tell us of the cause of his death and where is his body? We will be exploring the finale to this riveting tale in the following blog. Let’s go!

Wolsey Arrives at Leicester Abbey

From Sheffield Lodge, Wolsey began a weary journey, inexorably travelling southwards, towards London. According to Cavendish, the party lodged a night at another of the Earl of Shrewsbury’s residences, ‘Hardwick Hall’, known more commonly today as Kirby Hardwick (and not the more famous Hardwick Hall associated with the indomitable Bess of Hardwick). One night was also spent in Nottingham, although Cavendish gives no details of exactly where. Perhaps he stayed again at the archiepiscopal residence at Southwell, where he had lodged on his way to Cawood, some 18 months earlier.

It must have been a painful and exhausting journey for Wolsey. Along the way, Cavendish reports that his master ‘waxed so sick that he was divers times likely to have fallen from his mule’. However, somehow, Wolsey finally made it to Leicester Abbey on Saturday 26 November. There, the abbot and his brethren greeted the ailing Cardinal at the abbey gates by ‘the light of many torches’. Wolsey knew the end was fast approaching, declaring to the Abbot, ‘Father Abbot, I am come hither to leave my bones amongst you’.

Leicester Abbey: The Most Influential Augustian Abbey in England

Leicester Abbey, also known as the Abbey of St Mary de Pratis (Abbey of the Meadows) was an Augustinian monastery situated just one kilometre north of the medieval city of Leicester. It was the largest and one of the most influential Augustinian Abbeys in England. The monastery complex occupied about 13 hectares of land. It was home to around 24 canons at the time of Wolsey’s visit; these were not monks, but priests who worked in the local parishes and who lived under the rule of St Augustine. The ‘Black Canons’ (as they were called because of their dark, outer garments), were ‘supervised’ by an abbot; in this case, Abbott Pescall. He was notorious for his religious laxity and financial incompetence and was already under the close scrutiny of the powers that be in London – but that’s another story!

The entire compound was surrounded by a wall (which still survives). The main abbey church and conventual buildings were sited adjacent to the west bank of the River Soar, which meandered through the meadows in which the abbey had been built. The main outer gateway to the abbey compound, which Cavendish mentions in his account, was situated towards the middle of the northern section of the abbey’s perimeter wall. It remains the main entrance to the park today, but sadly, the gatehouse has gone (see image above).

A track led southwards to a second, inner gatehouse. Beyond that, a yard opened up directly outside the main west facade of the church and a range of conventual buildings, which ran directly southwards from the abbey church, forming the western range of the abbey’s cloisters. This range comprised of the Abbot’s lodgings, the most splendid and luxurious accommodation in the abbey (see image below).

We know from Cavendish’s account that ‘they brought him [Wolsey] on his mule to the stairs foot of his chamber, and there he alighted, and Master Kingston then took him by the arm and led him up the stairs’. So, we know for sure that Wolsey was housed in a first-floor chamber. It is quite possible that the Abbot ceded his own lodgings to the Cardinal. However, we cannot be sure, for another possible contender might be the guest lodgings, located across a small courtyard, south of the cloister.

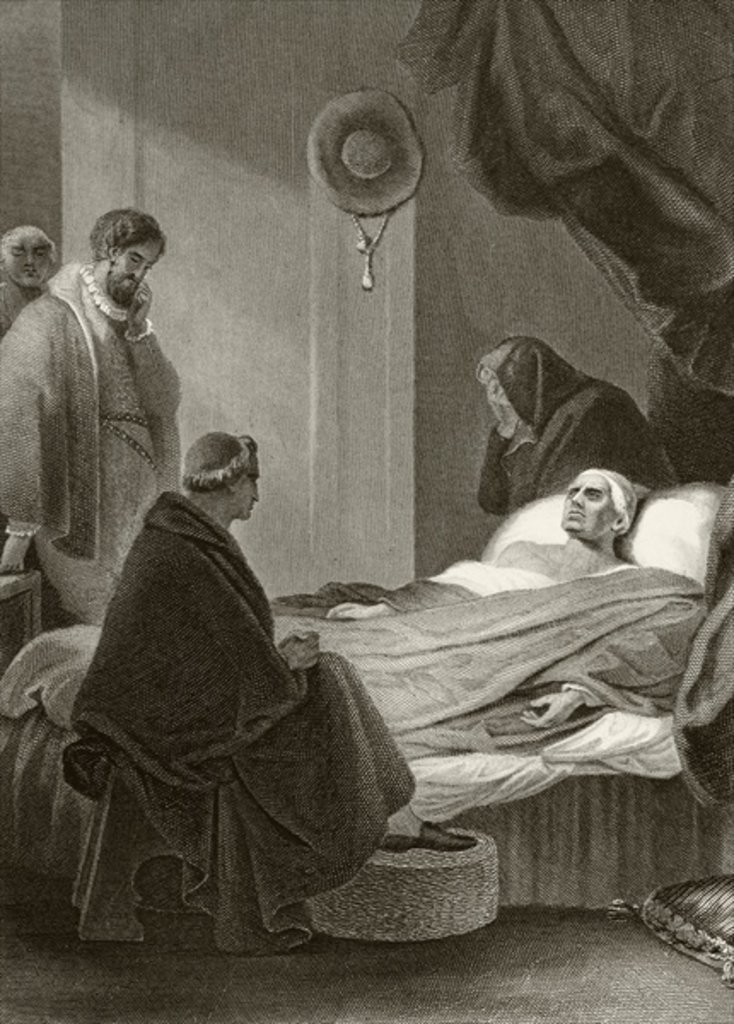

Having been escorted to his chambers, Wolsey went straight to bed and according to his gentleman usher, grew ‘sicker and sicker’. By the Monday morning, Cavendish felt that his master ‘was drawing fast to his end’. He describes standing by Wolsey’s bedside, the window shutters closed, the wax tapers burning, casting a willowy light around the room. Wolsey roused from semi-consciousness, asked who was there and what was the time. When Cavendish replied that it was eight o’clock, the Cardinal became distressed, saying, ‘Eight of the clock? That cannot be…it cannot be eight of the clock. For by eight of the clock, ye shall lose your master. For my time draweth near that I must depart out of this world’.

After dinner which, in Tudor times, was served in the middle of the day (11.00 am or noon-ish), Master Kingston called Cavendish to his chamber. Back at Cawood, the Earl of Northumberland, Henry Percy, had stayed behind to dismantle the Cardinal’s household. Having found evidence that Wolsey had sequestered £1000 somewhere (a massive amount of money at the time), the king had been informed. He, in turn, commanded Kingston to question the Cardinal and find out where the money was stashed.

Cavendish warned the Constable of the Tower to make haste in his questioning, for he feared the Cardinal would ‘not live past tomorrow in the morning’. Kingston duly went to the Cardinal’s bedside. What followed was a strange conversation between the two men: Kingston demanded to know where the money had come from and where it could be found; the Cardinal listed the names of those he had borrowed the money from, but declared in the end that ‘while he would not conceal it from the king’, and that he would gladly ‘declare it’, Master Kingston should ‘have a little patience’ with him. Despite the Cardinal being in extremis, Kingston settled for Wolsey’s promise that he would reveal where the money was to be found the following morning.

Through the night, Wolsey ‘waxed very sick…and often swooned’. At four o’clock in the morning, he roused from his semi-conscious state and asked for a little meat, verbally boxing Cavendish’s ears for not having any prepared and at hand. Of course, Cavendish immediately called up the cook, then Wolsey’s chaplain, Master Palmes, and finally he went to William Kingston. He warned the latter that ‘my lord will not live’ and that he should make haste to the Cardinal’s bedside for he was ‘in great danger’.

Kingston was not impressed, chastising Cavendish for making the Cardinal believe he was sicker than he actually was! Nevertheless, despite his misgivings, Kingston returned once more to the Cardinal’s chambers. It was seven o’clock on Tuesday 29 November.

What follows is an extraordinary speech by Henry’s erstwhile first minister. Firstly, he knew he was dying. He declared that having had a fever and ‘flux’ (diarrhoea) for eight days, the outcome could only be either ‘excoriation of the entrails, or frenzy or else imminent death’. Wolsey preferred the latter. It ‘was the best remedy of the three.’ Then Wolsey made his now-famous declaration; that if he had served God as diligently as he had done the king, He would not have given [him] over in his grey hairs.

The Cardinal reasserted that he had served the king faithfully, even in the ‘weighty matter yet depending’ (meaning the King’s divorce from Katherine of Aragon). He recalled how many times he had knelt before Henry VIII in his privy chamber ‘the space of an hour or two’, begging him to change his mind on a matter – and yet had failed. Thus, he gives his warning to Kingston; ‘to be well advised and assured what matter ye put in his head, for ye shall never pull it out again’. After a final tirade about the necessity to defend against the spread of Lutheran heretics in the realm, Wolsey’s speech began to falter and ‘his eyes were set in his head as his sight failed him’. The Cardinal’s body was shutting down.

Abbot Pescall delivered extreme unction according to Catholic rites. As the clock struck eight in the morning, as the Cardinal predicted, he ‘gave up the ghost’. Thomas Wolsey was dead.

I have read accounts stating that because of his profuse diarrhoea, Wolsey must have been suffering from dysentery, but from Cavendish’ account, this is clearly not so. So what did kill the Cardinal?

What Killed Cardinal Thomas Wolsey?

Cavendish states very clearly that Wolsey’s symptoms were a combination of upper gastrointestinal wind, followed by profuse diarrhoea which was ‘wonderous black’. I trained as a medic and admitted many such patients to the hospital, who were experiencing similar symptoms. It is the black diarrhoea that clinches the deal; although it would have been even better if Cavendish had recounted the foul stench which invariably accompanies this symptom. We can be in no doubt that Wolsey’s cause of death came from prolonged bleeding from his upper gastrointestinal tract, i.e. his stomach or his duodenum. This was most likely from a ruptured peptic ulcer or a tear in the lining of the stomach. Nature probably saved the Cardinal from a brutal end, delivered by an executioner’s axe.

The Burial of Thomas Wolsey at Leicester Abbey

After his death, a messenger was dispatched to London to tell the king of the passing of the ‘Cardinal of York’. At the same time, the mayor of Leicester and his brethren were sent for, so that they could witness the corpse. Clearly, Kingston did not want to find himself on the wrong end of an accusation that he had spirited the Cardinal away to safety!

When Wolsey’s body was removed from its bed, a hair shirt was found underneath his smock of the finest linen, Holland cloth; a thing known only to his chaplain, according to Cavendish. There is no record of the body’s entrails being removed, nor of it being embalmed, as was often the case with high-status aristocrats. Instead, Wolsey was lain in a coffin of boards, wearing not only his hair shirt but all the ‘vestures and ornaments as he had been professed in when he was consecrated bishop and archbishop, such as ‘mitre, crozier, ring and pall’.

Wolsey lay in his coffin (presumably in his chamber) until ‘four or five of the clock at night’ so that ‘all men might see him dead there without feigning’, whereafter he was conveyed to the church, ‘with many torches alight’. His corpse was set in ‘Our Lady Chapel’, to the north of the chancel in the abbey church. Wax tapers were placed around the coffin, which burned throughout the night, while the canons sang dirige. At four o’clock in the morning, Mass was said and afterwards, the Cardinal’s body was finally committed to the ground. But here’s the thing. Where is the Cardinal’s body? The answer is no-one knows!

There have been several attempts to locate Wolsey’s lost tomb in both the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when extensive digs were carried out on-site. Despite Cavendish’s clear account of the Archbishop of York being buried in the Lady Chapel, the exact location of his tomb remains a mystery – no-one has yet been able to find his body. And what a discovery that would make; one of the most powerful men in Tudor England, dressed in full religious regalia!

Following the discovery of Richard III, who was buried in Greyfriars in the medieval city of Leicester, there have been renewed calls to try and find the final resting place of Thomas Wolsey, the man who Cavendish recalls was ‘once the haughtiest man in all his proceedings that then lived’. But until then, Wolsey remains elusively out of our grasp, just as he eluded Henry’s ‘justice’ nearly 500 years ago…and in the meantime, I am left wondering if Henry ever did get his hands on that £1000!

If you wish to visit the site of Leicester Abbey, check out the Abbey Park information page.

Thank you for an interesting article on the final days of Cardinal Wolsey casting light on an elusive part of Tudor history. Well illustrated and another location has been added to my growing list!

Thanks Barry! It is a fascinating account by George Cavendish. Although there is not too much to see there, I think it is worth a trip.

I forgot to add that an excellent publication on Cardinal Wolsey is “The Kings Cardinal” by Peter Gwyn, published by Pimlico.

Thanks for the recommendation!

Great article. Will travel up to see the abbey next year.

Wonderful! Thanks for the feedback.

do not expect to see a lot in abbey park it is mainly given over to a recreational area. however if one is parked near the park it is only a 30 min walk into leicester to visit the richard the 3rd exhibit and he himself is burieb but a few yards away . leicester is not a fine city so do not have high expectations

Funny! I was just there today doing some filming. You are right. I think I will add a couple of para about other things t see while in the area. Thanks for dropping by!

The cardinal initiated reforms in the Church IN England before the Reformation hit with all it’s fury and destruction, closing, for example, several religious communities that had gone off track. He also initiated legal reforms which benefitted the common people. Wolsey was a mixed bag, as are we all. He deserves to me remembered and memorialized as the good person that he was, another victim of a king who ripped an entire nation away from its’ ancient religious and spiritual heritage in his quest for a male heir. Ironically, Henry’s daughter Elizabeth proved to be a better monarch in many ways that was he.

My uncle Robert (d.1998) and myself Richard C.Woolsey studied the case of Thomas Cardinal Wolsey for years and come to the conclusion that he was poisoned en route to London to avoid the problems that might arise from trying a cardinal ,and Lord Chancellor of England for treason.How much more convenient if he died.

Umm..are you a physician? if you are, I’d be interested in hearing how the symptoms match more closely than that of an upper GI bleed.

Fascinating article.

In 1722, antiquarian William Stukeley arrived at Leicester and wrote an account of his visit to the Abbey in Itinerarium Curiosium. Even then there was little left standing. The gatehouse which had been converted to a ‘dwelling house’ was ‘spoiled of floors, roof and windows’ and left ‘daily to ruin and pillage’. According to his account, three years earlier a body ‘supposed to be Cardinal Wolsey’ had been dug up in the garden that was laid over most of the ‘wholly erased’ church. Stukeley was shown the spot where ‘has been much search for the famous cardinal’s body’ but the antiquarian did not consider it a ‘likely place’.

It would be interesting to find out more about this exhumation in 1719 and what happened to the body.

Ooh! Interesting. I know of Mr Stukeley but not heard of this account. It certainly would be interesting…if I ever get a moment, I’d love to do a bit of digging. Let me know if you ever come up with any more info. BW Sarah

Whilst researching the boundary dispute between the two Nottinghamshire villages of Blidworth and Farnsfield 1630 -1730, I came across a hand drawn map dated 1764.

This map clearly shows the position of a road side Stone marked as “Abbots Stone” The stone is shown at the junction of A614 and Millenium Way.

I am unable to find the origin of the stone. The A614 and the A1 (Great North Road) is the route one would take when travelling to Nottingham from Yorkshire.

It occurred to me that Cardinal Wolsey and his companions would have taken this route albeit also the route towards Kirkby Hardwick.

Wolsey’s journey to Leicester in November 1530 would have been 200 years prior to the boundary dispute map of 1764, and 500 years to the present day.

Either through ignorance or carelessness’ the stone would seem to have disappeared. I have searched the area as much as possible but it is a very busy road junction. There is a farm building close by and I may ask the owner if I could look into their land that is adjacent to the road.

Kirkby and Sutton in Ashfield are close to the site of Kirkby Hardwick. Sutton in Ashfield has 2 streets and a school with a possible Cardinal connection. Carsic and Priestsic roads and Priestsic Primary School.