Sutton House & Tudor Hackney: Ralph Sadler’s Nouveau-Riche ‘Bryk Place’

In this month’s blog, I will introduce you to a Tudor house that is utterly unique. You will not find another like it anywhere: Sutton House in Hackney. It was created by a Tudor courtier on the rise, not yet wealthy enough to build a grand country mansion or townhouse and yet of sufficiently elevated position to merit a home that was grander than a simple merchant’s house. The Sutton House monograph calls it a ‘small gentry house’ with ‘no direct parallels’. On these grounds alone, a visit to Sutton House is a must for any keen Tudor time traveller.

In writing about Sutton House, my quest – some might say ‘obsession’ – to detail the great houses belonging to Thomas Cromwell and his circle continues. Having written about Tudor Stepney and Cromwell’s ‘Great Place’ in the last blog and the divine Leez Priory belonging to Sir Richard Rich earlier in the summer, I now turn my attention to a new ‘man of the moment’: Sir Ralph Sadler (also written ‘Sadlier’) and the house he built for himself and his family as his fortunes were on the rise.

If you are unfamiliar with this gentleman of the court, I guarantee that once you begin to read about this fascinating character and his eventful life, you will be hooked – as I have been. He was close to or at the centre of, many momentous events that unfolded over his 51-year career at court, from triumph to tragedy, from the ordinary to the extraordinary. Ralph witnessed it all, nearly coming close to ruining himself on three separate occasions.

So, let us briefly touch upon the highlights of his career before looking at the house that this young, aspiring courtier built for his family in the ultra-swanky and sought-after Tudor parish of Hackney in Middlesex. But stay tuned, for before we finish our story, we will look again at Sadler’s scandalous personal life when a figure from the past resurfaced with potentially disastrous consequences.

The Meteoric Rise of Ralph Sadler

Ralph Sadler’s stellar success was facilitated by the rise to prominence of his friend and patron, Thomas Cromwell, through the 1530s. Sadler had been born in Hackney in 1507 and placed in Cromwell’s household as a child when he was seven years old. Perhaps we might imagine Ralph and other young Cromwell protégés gaining a fine renaissance education at Cromwell’s city residence, Austin Friars, just a few miles south-west of Hackney. By the time his education was complete, Ralph was fluent in French, Greek and Latin and had some knowledge of the law – unsurprising given his master’s profession.

As it turned out, Ralph had the good fortune to be apprenticed to one of the most accomplished men in the land. At such close quarters, he was well-placed to learn from his master’s genius for business, law and politics. As a result of his abilities, at the tender age of 19, Sadler became Thomas Cromwell’s Principal Private Secretary. This was a position of the highest order of trust; all of Cromwell’s paperwork would have come through Sadler, and the young man would have been at the heart of his master’s affairs. The esteem in which Cromwell held Ralph is reflected by the fact that in 1529, Ralph Sadler was made an executor of Cromwell’s will.

In the early 1530s, Thomas Cromwell’s rising fortunes began to eclipse those around him, and young Ralph surely benefitted from holding onto the coattails of his powerful patron. However, without innate talent, it is unlikely that Henry VIII would have plucked the young courtier away from Cromwell’s service. Ralph often acted as a day-to-day go-between between his master and the king. Thus, Sadler readily came to the king’s attention. In May 1536 (possibly as a result of the cull of the Boleyn faction, when places became available in the King’s Privy Chamber), Ralph began his long and illustrious service to the Crown by being appointed as a Gentleman of the King’s Chamber.

He seems to have been the perfect courtier; not only was he learned, intelligent and resourceful, but Ralph was also known for his feats of horsemanship and abilities at falconry. In April 1540, just as his erstwhile master was being raised to the aristocracy as the Earl of Essex, Ralph stepped in to fill the role of Henry VIII’s Principal Secretary, a role he held jointly with another of Cromwell’s men: Thomas Wriostheley.

Despite the dramatic fall of Thomas Cromwell in June 1540, Sadler continued to carve out a successful career for himself, which ultimately spanned the reigns of four Tudor monarchs. And it was quite some career! I have included some of the highlights below. However, for those curious to know more, I will attach a link to a more fulsome account at the end of this blog.

The Court Career of the Remarkable Ralph Sadler

In January 1537, after an initial, successful diplomatic foray into Scotland, Sadler became known as THE go-to man on Scottish affairs, a theme that would continue throughout the remainder of his life. (Indeed, he would be knighted after the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh in 1547.)

However, three years later, events took an unexpected and dangerously dark turn when Thomas Cromwell was arrested for treason on 10 June 1540. Sadler was also briefly thrown into the Tower, alongside Sir Thomas Wyatt and Sir John Wallop, as reported by both French and Imperial Ambassadors, Eustace Chapuys and Charles de Marillac. However, clearly, there was no concerted will to bring him down, and Ralph was released just a few days later. Sadler had survived his first brush with potential ruin.

The second came some years later, following the death of Edward VI. As a committed Protestant, Ralph signed the Device for the Succession, placing Lady Jane Grey on the throne of England in 1553. For his troubles, when Mary I acceded just nine days later, he was stripped of all his offices and placed under house arrest at Standon Lordship in Hertfordshire between 25 and 30 July, before being pardoned on 6 October.

Thereafter, wisely, Ralph lay low during the reign of the Catholic Queen, Mary I, partially retiring to his country seat at Standon Lordship. However, he was not idle during this time, apparently riding the 17 miles or so to nearby Hatfield House regularly, there to coach the young Princess Elizabeth on the art of diplomacy and politics. Perhaps Ralph Sadler had more to do with Elizabeth’s phenomenal grasp of courtly intrigue and how to navigate it than many people might realise.

The sun shone again for Sadler with the accession of Elizabeth in 1558. Ralph regained royal favour. His court appointments inveigled him once again in Scottish matters, becoming briefly the gaoler of Mary, Queen of Scots at Tutbury Castle and Wingfield Manor in Derbyshire in 1584. By this time, Ralph was an old man of 77 and was probably done with the cruel machinations of court life and royal politicking.

Thus, it was a position that he fulfilled reluctantly, writing to Elizabeth I’s Secretary, Francis Walsingham, requesting that Walsingham apply his ‘good helping hand to help to relieve him of his charge as soon as it may stand with the queen’s good pleasure to have consideration of his years and the cold weather now at hand.’ His wish was only granted the following April. Sadler had given the Scots Queen more freedom than the likes of Cecil and Walsingham preferred, the latter stating that Mary might henceforth ‘receive more harder usage than heretofore she hath done.’

by Dave Harris via Creative Commons Attribution 3.0

One of the last acts of Sadler’s momentous life was to sit at Mary’s trial. He would die in his bed at his country mansion in Standon Lordship, Hertfordshire, just six weeks after the demise of the Scots’ Queen on 30 March 1587.

But what of Sutton House, the house that Sadler had built as befitting his rising status at court in the 1530s? It is this historic building that we will pay our attention to next.

Sutton House and Tudor Hackney

Today, Hackney is subsumed into urban London, a suburb that merges seamlessly with the heart of the city. However, back in the sixteenth century, this was far from the case. Dr William Robinson, writing in the ‘History and Antiquities of Hackney‘, states that ‘In former times…many noblemen, gentlemen, and others, of the first rank and consequence, had their country seats in this village on account of its pleasant and healthy situation.’ Indeed, it seems to have remained remarkably free of pestilence and plague when surrounding areas were sorely afflicted.

Its proximity to the City of London, lying just three miles to the northeast of Bishopsgate (one of the principal gates in London’s city walls), made Hackney a sought-after residential area for the nobility and aspiring courtiers alike. The English Heritage monograph on Sutton House calls the early sixteenth-century Hackney a ‘prosperous country satellite of London.’

The village was centred around the parish church of St Augustine (only its early tower survives) and the main street, unimaginatively called ‘Church Street’. A handful of other lanes connected a smattering of principal buildings, while a stream called The Lord’s Stream, or Hackney Brook, ran through the village to the south of the church.

Otherwise, this was a rural parish with houses surrounded by fields and gardens. Its produce (including hay to feed the horses of London) commanded reasonable prices in London markets. In 1535, the year before he was appointed one of Henry VIII’s Gentlemen of the Privy Chamber, Ralph Sadler, began building a stylish new house in the village of his birth. In later generations, this building would become known as Sutton House (what we will call it here). However, at the time of its construction, contemporary documents dated from when Ralph Sadler sold the house in 1550 suggest that it was informally known as ‘Bryk Place’ because it had been built of the newly fashionable red brick.

The Appearance of Sutton House

Sadler, of course, had seen the great royal palaces of the day. His master, Thomas Cromwell, had been a prodigious builder; he had managed several of Wolsey’s and then the king’s major building projects. Working alongside Cromwell, Ralph would have become familiar with the latest trends and the master craftsmen who turned dreams into reality. Although his pocket could not yet stretch to building a mansion house (that was to come), he could afford to build a notable home that would reflect his status as a man on the ‘up’.

In fact, Ralph had a fine line to tread in creating his Hackney home. According to Sutton House: A Tudor Courtier’s House in Hackney, Sadler was ‘careful not to unsettle or threaten’ those of higher rank by sticking to elements that had been a part of house building since the medieval period. Yet through his close associations, he was also able to inject some of the latest fashions into his building project. Thus, the appearance and layout of Sutton House are unusual.

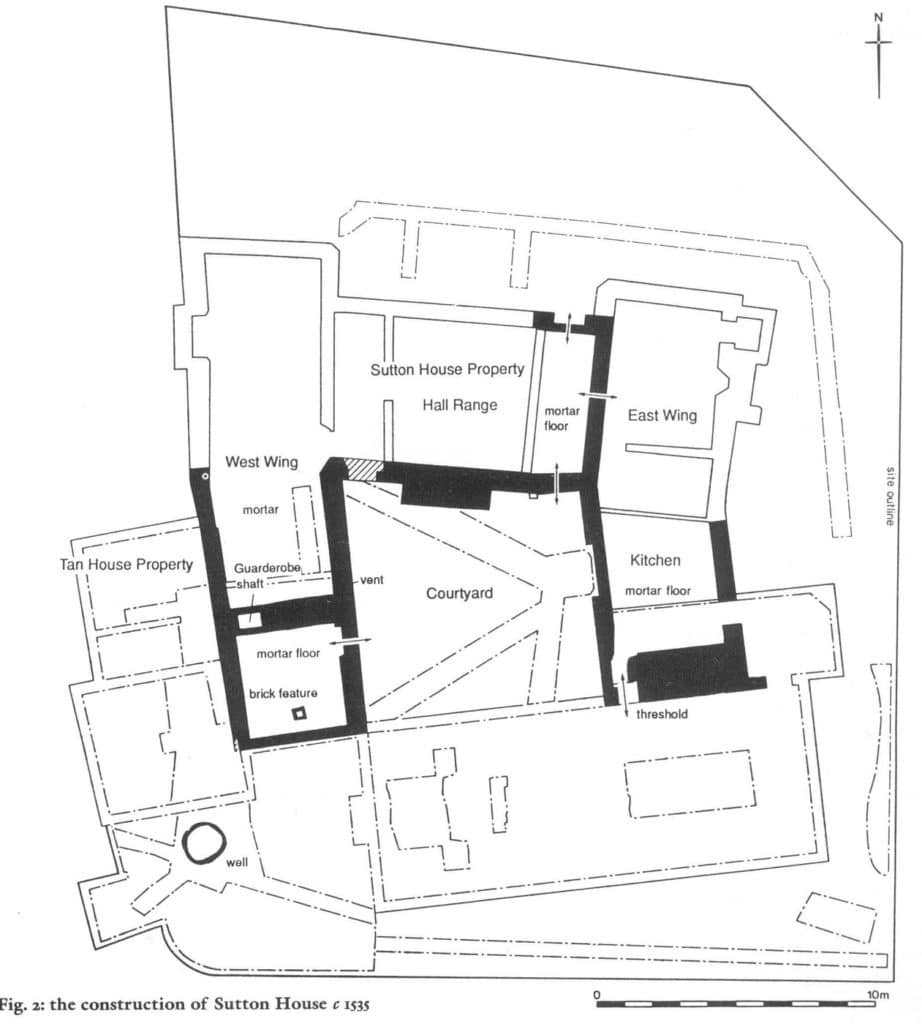

It was to be an ‘H’ shaped building with a small courtyard to the rear, an arrangement rooted in the medieval period in so-called ‘double-ended hall’ houses. The building rose over four floors, including the cellars, and was constructed from red brick. It was decorated on the exterior with diapering. Although the house underwent significant changes during later centuries, including the addition of a Georgian facade, some of this brickwork and diapering can still be seen today.

Two staircases, one in the west and one in the east wing, gave access between floors; the one on the west was primarily used by servants, and the one on the east was for family and guests.

In all, Sutton House was a miniature version of the great houses and palaces that Sadler visited frequently. A ‘Great Hall’ (now lost) was the principal reception centre on the ground floor, forming the crossbar of the ‘H’. The east wing, accessed via a screen’s passage from the low end of the hall, contained a lower parlour. The precise use of this room is unknown. The Sutton House monograph postulates that it could have been a service room. Still, its grand fireplace suggests a higher status use, possibly as a private dining room for the family or a room for Sadler’s Chief Steward, Gervase Cawood.

Toward the back of this wing was the kitchen. This survives and is, again, a miniature version of the great kitchens of the houses of the nobility.

Off the high end, in the west range is the parlour, the monograph states that this was ‘one of the key rooms of the house’ and was most likely used ‘as an everyday sitting and eating room and a space for entertaining guests’. A large Tudor fireplace dominates one wall of the room, while the walls are clad in magnificent, linen-fold panelling. Shockingly, this was brazenly stolen in broad daylight during the 1980s by men posing as workmen. Thankfully, though, the panelling was recognised by the dealer who was offered it – and ultimately returned to the house.

Above the Great Hall was the Great Chamber, measuring nine by 5.5 m. This was a more private reception room reserved for entertaining honoured guests. In my opinion, this is one of the most impressive spaces to survive. Its oak panelling, glorious Tudor fireplace and double-joisted floor that made it perfect for dancing are all authentic. Sadly, the windows are later Georgian replacements. But what most blows your mind when you visit is the notion that within this space, Ralph must have entertained his friend, Thomas Cromwell. Goodness knows what conversations went on in this room!

Off the high (east) end of the Great Chamber (connected directly to it) is another chamber, most likely used as a Withdrawing Chamber. As the name suggests, its purpose was to provide a place for the host and guests to withdraw for greater privacy or while the Great Chamber was being rearranged for after-dinner entertainment. On this east side, toward the back of the house, was another room, probably a bed-chamber that could be used by guests or, possibly, Sadler’s steward.

This general arrangement of a chamber leading off the Great Chamber was repeated on the west side. The room leading directly off the Great Chamber was most likely the principal bed-chamber used by Ralph himself. It was not only used as a place to sleep but also as a place to retire to during the day, as was commonplace during the era. Again, a further inner chamber to the rear of this room was likely a private bed-chamber, possibly used by Sadler’s wife, Ellen (sometimes referred to as ‘Helen or even Eleanor’)

Now, while we are talking about Helen, I think it is the perfect time to return to the third occasion that could well have derailed all that Sadler had thus far successfully strived for.

A Scandalous Marriage?

Ralph Sadler married Ellen around 1534. The two met via Thomas Cromwell, although Ellen’s link with Thomas is disputed. Some accounts say she was employed by him. There is also the suggestion that she was Thomas’ first cousin. This seems more likely since Ralph was already coming into his own and would be looking for an advantageous match. Ellen was (or so she thought) a widow with two daughters from her previous marriage

Her late husband was a ne-er-do-well named Matthew Barre from Sevenoaks in Kent. He had vanished at some point during their marriage. Despite searching for him for some considerable time, Ellen never found Matthew and was at one point told he was dead. Thus, when Ralph and Ellen married in 1534, they did so in good faith.

The couple went on to have seven children together. We can imagine that Sutton House must have been a bustling household, full of children and laughter, since Ralph and Ellen were happily married. Then, in 1545, Ralph received shocking news while on an embassy in Scotland. Ellen’s ‘dead’ husband had miraculously appeared in London, bragging about the fact that he was married to Ellen. By then, of course, Sadler was a wealthy and prominent man about town and would have been well-known to Londoners.

According to the law, this meant that Ralph and Ellen’s marriage was bigamous and their children illegitimate. Ellen was technically no more than a whore, and the whole honour and integrity of the family were suddenly at stake. According to Lord Chancellor Wriostheley (Sadler’s old partner in crime as Henry VIII’s Principal Secretary), Ralph ‘took his matter very heavily’. He would have no legitimate heir, and his successful career, which had been built so painstakingly over more than two decades, was under threat.

As a result, Sadler had to draw in favours from his many connections, ensuring that an Act of Parliament could be passed ratifying Ralph and Ellen’s marriage. The extent of goodwill Ralph had built up with those in positions of power meant that the Act was never made public. In this instance, the dirty linen was most definitely washed behind closed doors!

Ralph and Ellen’s good names were preserved and the former’s career continued to flourish but it is possible that this incident did have an impact; some have postulated that without it, might Ralph Sadler have gone on to be enobled, becoming part of the English nobility. As it is, when Ralph died in 1587, he is said to have been the wealthiest commoner in England.

The Sadlers Leave Sutton House

Four years after this scandal broke, Ralph sold ‘Bryk Place’ to John Machell, a ‘highly successful cloth merchant from the City of London’. The two likely knew each other well; John provided cloth to the royal court, and, at the time, one of Salder’s royal appointments was as Master of the King’s Wardrobe.

By this time, Ralph was wealthy enough to build a grand country house called Standon Lordship in Hertfordshire. The building was commenced in 1546. So, when Sutton House was sold, this magnificent single courtyard house, entered by a turreted gatehouse, rivalled those of many of his contemporaries. Ralph had finally ‘arrived’ and, in no small part, to his erstwhile master, Thomas Cromwell.

However, unlike Cromwell, who had garnered so many enemies and too much power, Ralph survived to tell the tale and, as mentioned above, died in his bed at Standon Lordship, aged 80, on 30 March 1587. He is buried in a splendid tomb, which can be seen in the nearby parish church.

Sutton House had a very varied and colourful history before becoming the National Trust’s property in the 1930s. It was only fully open to the public in 1994.

There are ‘ghosts’ everywhere in Sutton House; the building still feels alive with the tangible energy of those long past. When I visited, it was easy to imagine members of the Sadler household brushing past me, going about their everyday business, or eavesdrop on a private conversation as Ralph entertained his friend, Thomas Cromwell, in the Great Chamber over dinner. There is even a paw print of a Tudor dog, frozen in time in a tile on display down in the cellar – something that famously caught Hilary Mantel’s imagination as she penned the Wolf Hall trilogy. I can understand why!

As a unique architectural and historical survivor of the early sixteenth century, it is a ‘must-see’ for any Tudor-loving aficionado. For all the latest information on when and how you can visit, check out all the latest visitor information via the Sutton House website.

Sources

The following sources have been useful in writing this blog:

Sutton House: A Tudor Courtier’s House in Hackney, by Belcher, Bond, Gray and Wittrick (available for sale at Sutton House)

Biographical Memoirs, by Sir Walter Scott. Volume I. 1830, p 71-143

The Northern Suburbs: Haggerstone and Hackney. British History Online. Old and New London: Volume 5. Originally published by Cassell, Petter & Galpin, London, 1878.

You can find out a little more about Ralph Sadler’s life here.

The most notable biography of Ralph Sadler is this one: Politics and Profit: A Study of Sir Ralph Sadler 1507-1547, by A.J. Slavin

Superb

I’ve been catching up on all things Tudor Travel Travel Guide and Sutton House is now on my list of places to go. Thank you!

Excellent! A podcast that I recorded at Sutton House last year will be out in March BTW

Ralph Sadler caught my interest through Hilary Mantel’s books but I had no idea how full a life he led. This was really enjoyable!

Thank you! Interesting and well-researched.

Thanks, Margaret!

Wonderful blog! Being a dog lover, the paw print frozen in time touched my heart.

Fran