Chesworth House & The Scandalous Undoing of Katherine Howard

This post contains some affiliate links

When Katherine Howard stepped upon the scaffold at The Tower of London to make her final speech of contrition, all the shocking details of the young queen’s earlier, scandalous life had been laid bare for all to see.

Much of the evidence that came to light in her indictment was given in evidence by friends and servants who had been part of Katherine’s life after she was sent to live at her step-grandmother’s household; this divided its time between the Duchess’ townhouse in Lambeth, called Norfolk House, and her country seat at Chesworth House, just outside Horsham in Surrey.

It was here that the thirteen-year-old Katherine would soon begin her first sexual flirtation with her music teacher, Henry Manox. It would be the first of three fatal ‘liaisons’ that at first must have seemed little more than scintillating and delicious fun to the young teenager but which later would cost Katherine her life at the hands of the executioner’s axe.

I have long been fascinated by the place where Katherine Howard laid the foundations for her ultimately bloody fate: Chesworth House, not least because it periodically comes on to the housing market with delicious images of the house, which hint at its earlier Tudor origins. So, in this blog, on the anniversary of Katherine Howard’s execution, we go in search of happier times at the lost Tudor mansion.

Chesworth House: A New Home for Katherine Howard

It is believed that Katherine Howard was born around 1523 (although her exact date of birth is unknown). She was the daughter of Edmund Howard, (the third son of the 2nd Duke of Norfolk), and Joyce Culpepper. Edmund suffered financially because of the progenitor laws governing England’s aristocracy at the time, which meant that almost all of a family’s wealth was concentrated upon the eldest son of a noble house. Thus, Edmund often had to resort to begging for money from some of his wealthier relatives and, at one point, was forced to relocate, some might say ‘flee’, to Calais to avoid the ire of his debtors.

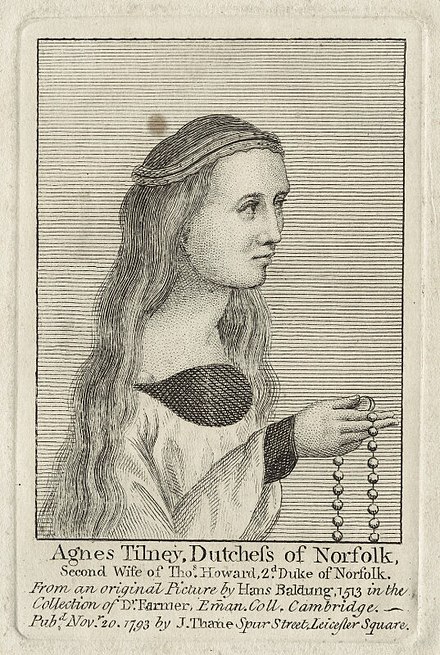

Katherine’s mother died around 1528, leaving Edmund to care for his young family, including Katherine, who was around five years old at the time. This would have been no small concern for a beleaguered Edmund, as Katherine had five half brothers and sisters by her mother’s first marriage and another five siblings of her own. As a result, Katherine, alongside some of her other siblings, was sent to live in the household of her step-grandmother: Agnes, Dowager Duchess of Norfolk, wife of the 2nd Duke of Norfolk. Also present was her aunt, Katherine, the Countess of Bridgewater.

Around the time of Katherine’s arrival in her household, Agnes would have been in her mid-50s, which was not an inconsiderable age for the time. According to one account, she was described as ‘stiff-necked, testy and old fashioned’. She certainly had an acid tongue and fiery temper. However, given the fact that she seemed, at the time, to know so little about what was going right under her nose, it might have been better if she had spent less time at her devotions (which she had a reputation for) and more time supervising the moral education of the youngsters in her charge!

As one of the premier families in the land, the Howards had a considerable property portfolio. They had largely abandoned the home that Agnes must have spent much of her married life in, Framlingham Castle, and instead made Kenninghall, in Norfolk, their principal residence.

As Dowager Duchess, Agnes made Norfolk House in Lambeth and Chesworth House in Surrey her two main residences (although, as part of her dower, she took ownership of 24 manors at the time of her husband’s death in 1524). Of these, it is said that she was very fond of Chesworth. It would have certainly been a fine country property located one mile south of the town of Horsham. According to the late Annabelle Hughes, a local historian with a deep interest in the history of Horsham and its notable buildings, at the time that Katherine Howard was in residence at Chesworth House, it would ‘have been considerably larger than it is now but never as grand as Kenninghall’.

The Layout and Appearance of Chesworth House

Sadly, today, just like Kenninghall, almost all of this once-grand Tudor mansion has been lost. Two ranges of the house have significant architectural features dating to the late fifteenth and early sixteenth century, part of the north-east and south-east ranges, respectively. Of these, the latter range is most obviously of Tudor origin. However, there is much that is not known about the original layout and appearance of the manor.

Hughes writes that we might assume there were parallels with Kenninghall – although on a smaller scale. We know that the house, which Katherine knew, had likely been built by the 2nd Duke of Norfolk to replace an earlier manor house that lay south of the current house, underneath the current croquet lawn. The river that runs through the present-day gardens most likely formed part of the moat of the original house, over which there was a drawbridge in 1427.

Of the current property (which has significantly been remodelled and renovated over the centuries), glimpses of its Tudor past still shine through. As stated above, the oldest part of the property is probably the most northerly block. This is dated circa the late fifteenth century. The range in the south-east, which is seen in the foreground of the picture above, is often referred to as a chapel, although, as Annabelle Hughes points out, there is no direct evidence of this.

To confuse matters even further, she states that the domestic chapel of the period might well look like any other ordinary room in the house when divested of all its religious regalia. So, its original purpose is obscure, but Hughes states that ‘documentary evidence strongly suggests that this range was known as ‘the Earl of Surrey’s tower”. Although it does not look very ‘tower-like’ today, it has ‘likely lost its first floor, and almost certainly an attic floor and its roof’.

Although it seems that little more can be discerned from the remains of the house today, we are lucky. An inventory of the property was taken on 20 January 1549 by Sir Thomas Cawarden and Sir William Goring. This was after the property was forfeited to the Crown following the attainder and execution of Thomas Seymour in 1549, who in turn had been granted the house following the execution of Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, in 1547!

The inventory names 20 rooms in all. Four more are implied, and seven service rooms or buildings are listed. Of those rooms specifically identified, we learn of ‘my Lord’s bedchamber’, the ‘inner chamber to my Lord’s Bed Chamber’; ‘Inner Chamber to my late Lord of Surrey’s Chamber’ and ‘Inner Chamber of my Lady of Richmond’s Chamber’ (Mary Howard, Duchess of Richmond). A hall, dining chamber (where a cloth of estate made of blue velvet ‘upon gold’ hung); a ‘closet, chapel and chapel closet, nursery, a ‘Nether’ and ‘Upper Tower’ chambers are all mentioned.

It is also clear from the inventory that the interiors of Chesworth House were already well past their best. Many tapestries and hangings are listed as being ‘verye olde’ or ‘sore woryne’. ‘Ragged curteyns’ are also mentioned alongside ‘pillows of downe, both good and bad’ and mattresses ‘thoroworyn and little worth’.

However, despite this, we can still snatch glimpses of Chesworth’s glory days when the house still thrived under Anges’ guardianship. For in the section that describes bed hangings, we read about one being of ‘tysshewe and red velvet, painyd, imbrodered with dropped of gold and another of ‘grene velvet and bawdekyn, imbroderid with crownes and stars’. Turkey carpets, a costly item in their day, are also featured.

The Goings-On in the Maiden’s Chamber and the Undoing of Katherine Howard

We would likely know nothing of the events at Chesworth House in the mid-late 1530s if not for Katherine Howard’s spectacular fall from grace. From seemingly nowhere, the teenager rose from obscurity to become Queen of England and consort of King Henry VIII in a matter of months.

Tragically, Katherine’s libidinous past and adulterous behaviour with Thomas Culpepper as queen would end her marriage – and life – within a little over two years. The revelations made by those who had lived alongside Katherine at Chesworth brought a delicately stacked pack of cards tumbling to the ground after only around 18 months of marriage to one of the most fickle and dangerous monarchs in Europe.

The complexities of Katherine’s rise and fall are outside the scope of this blog. If you wish to read more, I commend to you Gareth Russell’s book: Young and Damned and Fair: The Life and Tragedy of Catherine Howard at the Court of Henry VIII (link at the foot of this blog) or check out this video interview with Gareth on my YouTube channel. However, we will look at some of the evidence given against Katherine that highlights the likely shenanigans occurring during her time at Chesworth House.

The details of Katherine’s indiscretions have been frozen in time via the evidence given against the queen following her arrest in November 1541. Family members, friends and acquaintances were hauled in to be interrogated by Thomas Wriothesley, 1st Earl of Southampton and Lord Chancellor; Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury; and the Privy Council.

The spark that ignited the fire was a throwaway comment by a gentlewoman called Mary Hall, nee Lassels. She had spent time in the Dowager Duchess’ household at the same time as Katherine. After Katherine’s stellar rise at court, Mary’s brother, John, a religious reformer, urged his sister to seek a place in the new queen’s household. Mary’s reply was indignant; she felt sorry for Katherine, she said. When her brother asked her why, Mary replied that she was both ‘light in living and conditions’. Her brother would not let it drop, so he enquired, ‘How So? Mary replied

‘A certain Francis Dereham lay in bed with her in his doublet and hose between the sheet a hundred nights or more, and one of the maids in the house said she would share a bed with her no longer because she knew not what matrimony was. And another of the Duchesses’ servants, Henry Mannock [Mannox], knew of a privy mark on her body‘.

The cat was out of the bag.

John Lassels scurried off to report the conversation to Thomas Cranmer. It is not clear what Lassels’ motives were for telling tales. If he was a deeply religious man, perhaps it was rooted in self-righteous affront at Katherine’s scandalous behaviour, or perhaps it was simply concern that the king was yoked in marriage to a strumpet. Maybe Lassels, shrewdly, did not want to hold onto information that might eventually come back to strike the family down. It could be damaging, if not dangerous, to withhold something of this nature (something potentially treasonous) that might later come to light through another source.

However, I am struck by how this passing conversation between Mary and her brother is similar to the one that occurred between Elizabeth, Countess of Worcester and her brother, Anthony Browne, some five years earlier concerning Anne Boleyn’s morales. It was a similar throw-away comment by the Countess about Anne’s lax behaviour that was the catalyst that ultimately culminated in the destruction of the Boleyns.

Idle tittle-tattle, gossip or confessions by disgruntled or jealous servants of a noble household were an ever-present threat to a family like the Howards. By the time Katherine became queen, both her step-grandmother and her aunt, the Countess of Bridgewater, were, it seems, aware of her disreputable past. The ‘silence of many of these individuals’ was bought by securing their place in the new queen’s household. These two ladies, in particular, must have been holding their breath, hoping that Katherine’s inappropriate liaisons would not come back to haunt them. Sadly, this was not to be.

When Mary was brought before Thomas Wriothesley for further questioning, she recounted the ‘misconduct’ that had gone on between Katherine and Manox and that two others had carried tokens of love between them. She also named several others including the porter, two grooms of the chamber and ‘my lady’s chamberer, Margery’ as other witnesses would be able to ‘tell much’ about the queen’s indiscretions.

When she was pressed to tell more of what she knew of Francis Dereham, she spilled the beans regarding the carnal ‘goings-on’ between Katherine and Dereham, which took place in the ‘maiden’s chamber’, presumably in both Lambeth and at Chesworth House. The teenage girls, who slept together in a shared room, would let in certain young gentlemen at night after the duchess had retired to bed. Ungodly behaviour ensued, with banquets going on until two or three in the morning!

From here, more witnesses were questioned, and damning testimonies followed as the entire sordid affair unravelled. As I have said, it is not my intent to document these events here, fascinating though they are. However, alongside Katherine, Francis Dereham, Thomas Culpepper, Lady Rochford, Agnes, the Dowager Duchess, and the Countess of Bridgewater were also thrown into the Tower. At the time of her arrest on 11 December 1541, the Duchess was ordered to lock up her house Horsham. Happily, both ladies were subsequently released in May of the following year, having been pardoned by the Crown. The Duchess subsequently died three years later, in 1545.

We have already heard how the house was inherited (used) by Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey after Agnes died in 1547 and then after his attainder by Thomas Seymour until the latter’s execution in March 1549. It seems that the Howards regained the house as it was in the possession of the 4th Duke of Norfolk, which was the scene of his arrest in 1572 for his involvement in the Ridolfi Plot.

The Duke conspired to marry Mary, Queen of Scots and depose Elizabeth I. It seems that the Howards were rarely out of trouble! As usual, as a consequence of the Duke’s arrest and execution, the manor reverted to the Crown. According to British Listed Buildings, Chesworth House was occupied by various tenants, including the Bishop of Chichester (1577-82) and the Caryll family (c. 1586-1660). In 1660-61 the manor was settled on Queen Henrietta Maria and by 1674 on Queen Catherine of Braganza, who still held it in 1699.

From the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries, the status of the house declined, and Chesworth House eventually became a farmhouse. Over the centuries, much of the original Tudor mansion has been lost; later wings were built, and existing buildings were refurbished. Sadly, for us, it is now in private ownership and is not accessible to the public. However, while the house that Katherine knew barely clings on, I prefer to imagine Tudor Chesworth rise again, with its red-brick ranges, pretty gardens and orchards, where the ghostly laughter of a precocious young girl, who would arise from nowhere to become Queen of England, echoes across time.

Further Reading

Chesworth House was on the market back in 2018 for ‘offers over’ £6million. You can still see the online property portfolio here.

Chesworth, Horsham: The Story of a Local House, once the Focus of a Royal Scandal by Annabelle Hughes. Copies may be obtained by contacting Horsham Museum

Chesworth House on British Listed Buildings

Young and Damned and Fair: The Life and Tragedy of Catherine Howard at the Court of Henry VIII by Gareth Russell

Notes:

Katherine Howard is buried at the Chapel of St. Peter Ad Vincula at the Tower of London along with other famous Tower prisoners including Anne Boleyn, Jane Grey, and Thomas Seymour.

Really interesting – thank you. It almost makes you dizzy watching Tudors ( esp Howard’s!) whizz in and out of favour. How did they live. It is fascinating.