Doncaster, West Yorkshire

Distance Travelled from London: 242 miles

‘…and on Satirday came unto Doncaster, where he abode the Sonday and harde masse at the freres of Our lady and evensong in the parish church.’ The Herald’s Memoir

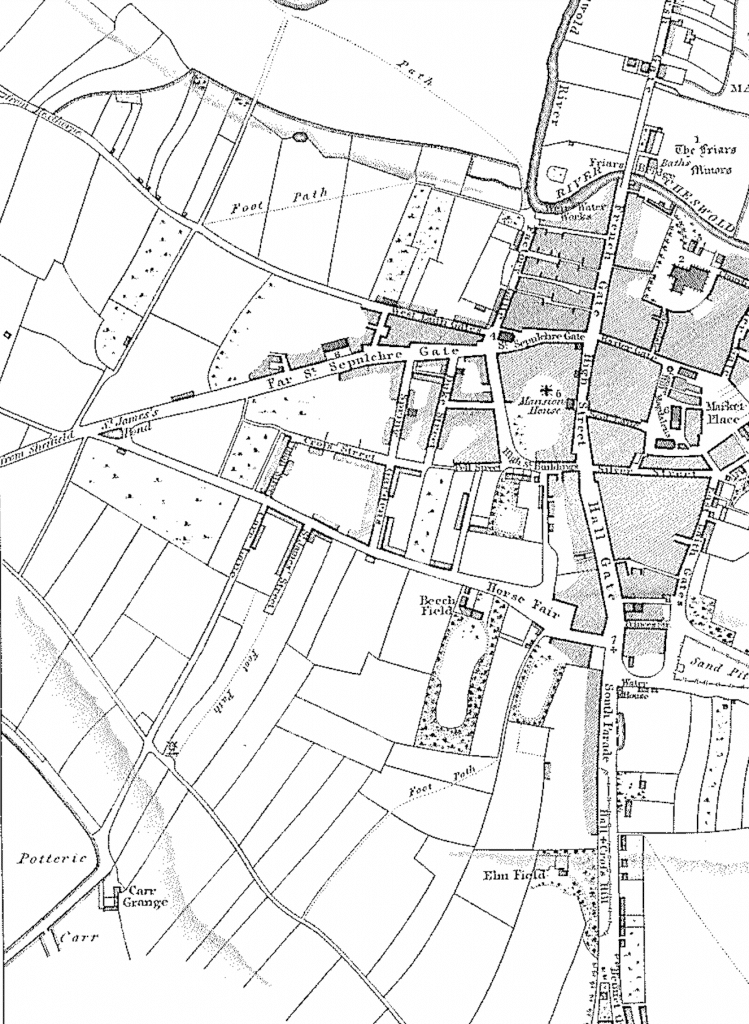

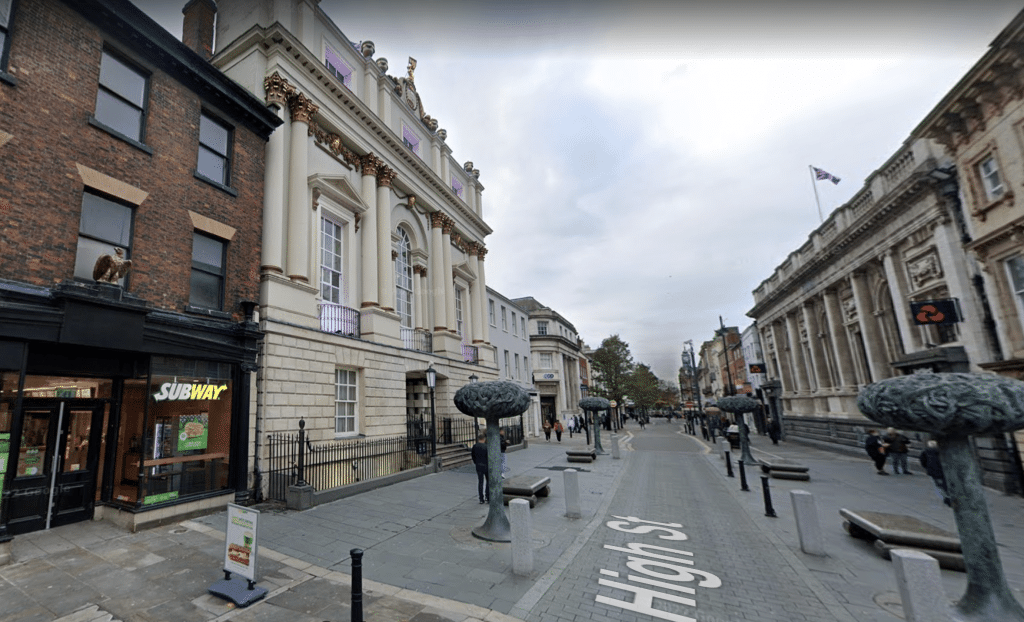

During the Tudor period, the Great North Road, which Henry was using to travel the final leg of his journey to York, ran straight through the middle of Doncaster via its High Street. At the time, this street was known as ‘Hallgate’. Unbelievably, this remained the case up until the mid-twentieth century when the town was eventually bypassed. However, this fact ensured that the next destination on our progress was oft’ used to house notable guests travelling north from London.

The Herald’s Memoir states that having left Nottingham, the King ‘came unto Doncaster’ on Saturday (15 April). Today, Doncaster lies in what became a highly industrialised area of Yorkshire; its oldey-worldy charms have been completely obliterated. So, to appreciate what sight greeted Henry as he approached the town from the south, we must turn to our trusted friend: the sixteenth-century antiquary, John Leland.

In his Itinerary, Leland describes the countryside surrounding Doncaster as having ‘good meadowland, corn and some woods’. The town’s houses were ‘built of wood and …are slated’. Although he notes that plenty of stone was around, it seems that the appearance of most of the town would have been of wattle and daub, timber-framed houses.

Leland’s account of the town in the first half of the sixteenth-century very specifically notes that ‘there was no evidence of Doncaster ever having a town wall’ but that there were ‘three of four gates’, the finest of which, in Leland’s opinion, was St Mary’s Gate, on the north side of the town.

Here, the River Don, which gave the town its name, skirted its northern edge, creating an island where the river briefly divided. At this point, the river was crossed by two stone bridges, one north of the island and one to the south (commonly known at the time, according to Leland, as ‘Friars’ Bridge’). This consisted of three stone arches, while the most northerly one was built with five. The latter also housed a chapel dedicated to ‘Our Lady’ and the aforementioned St Mary’s Gate.

Due to the presence of the river, this area was marshy; the island being home to the Greyfriars of Doncaster (hence the name ‘Friars’ Bridge). However, right across the other side of town, on its south side and directly fronting onto the Great North Road, was the location that we are particularly interested in. As the Herald’s Memoir states: ‘…and on Satirday [the King] came unto Doncaster, where he abode the Sonday and harde masse at the freres of Our lady’.

The ‘freres of Our Lady’ refers to the Carmelite Friary, situated in the south-west corner of the town. It was founded in 1350 by John of Gaunt, with additional royal patronage afforded by Richard II. Writing about the Carmelites of Doncaster in the nineteenth century, F. R Fairbank noted that this was once one of the best parts of the town. The six acres of land granted to the Whitefriars (as they were known because of the colour of their habits) was sandwiched between Hallgate (the High Street) and Sepulchre Gate and was moated around its outer, south-westerly edge. The current Printing Office Street follows the site of the original moat.

Here, the Carmelites created their Priory. The entrance gate was opposite Scot Lane, where the current Georgian mansion house now stands. Little is known of the exact appearance or layout of the Priory. However, of course, there was a priory church in honour of St Mary, some living accommodation (which in part must have been luxurious enough to attract several royal visitors over the centuries), and a very important, early shrine to ‘Our Lady of Doncaster’. This latter shrine was the most important Marian shrine in Yorkshire and is also considered to be one of the most significant in England, next to the likes of Walsingham, Canterbury and Westminster.

Therefore, it is not surprising that once again, we see Henry bowing to the precedent of England’s lineage of kings, hearing Mass in front of the shrine on Sunday 16 April, before crossing the town to the local parish church of St George to hear Evensong.

The Parish Church of St George

In truth, the Herald’s Memoir does not name the parish church attended by Henry on that Sunday evening in question. However, it is clear that St George’s, situated in the centre of the town, was the most significant church in Doncaster at the time. Henry would have had to parade through the town to reach the church – perfect for a king wishing to be seen by as many of his Northern subjects as possible!

Tragically, the church that I suspect Henry visited that day was utterly destroyed by fire in February 1853, taking with it the irreplaceable medieval library sited above the south porch of the church. The celebrated architect Sir George Gilbert Scott (who designed the current Houses of Parliament) built the current Minster church. While you may well wish to visit, it will sadly, I fear, never be a satisfactory replacement for its medieval ancestor.

The End of the Carmelite Priory

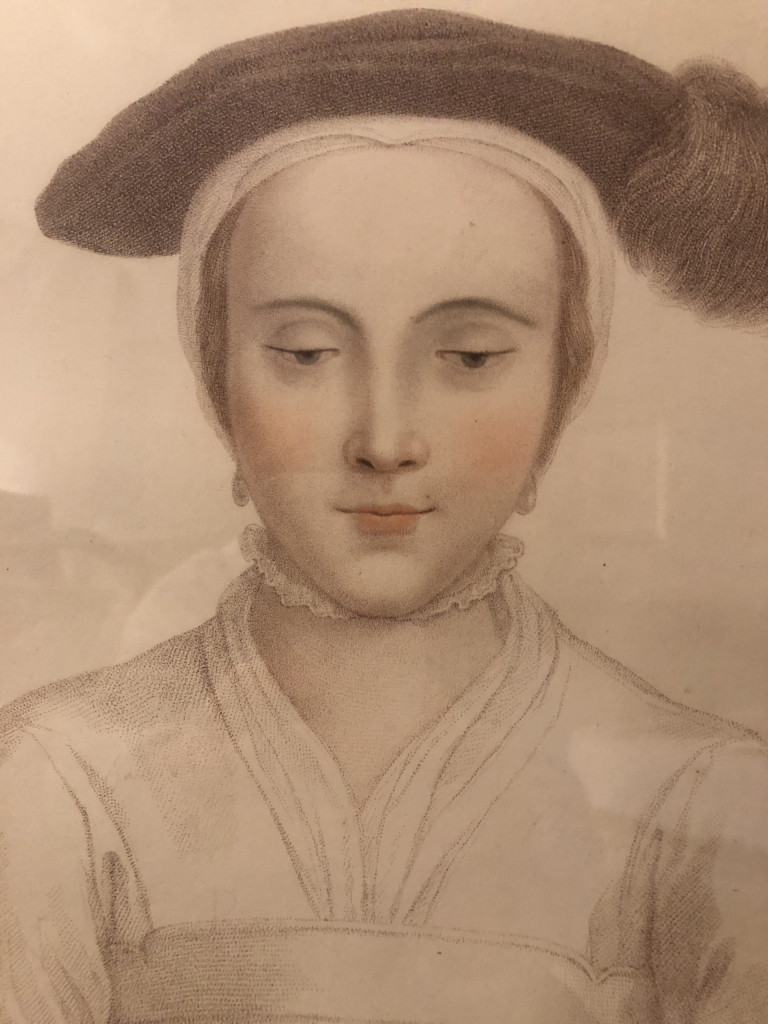

As I have already mentioned, several nobles, kings and queens visited the Carmelite Priory at Doncaster; amongst the roll call are Henry V in 1399, Edward IV in 1470, as well Henry VII’s daughter, Margaret, who was en route to Scotland to become James IV’s Queen in 1503. It is quite touching to notice how Margaret stayed in some places that had welcomed her father nearly twenty years earlier.

At the Dissolution of the Priory in November 1538, the confiscated goods consisted of ‘25 oz. of gilt plate, 109½ oz. parcel-gilt, and 48½ oz. white plate’, as well as ‘land rental for the site, buildings, gardens and orchards of £10 per year, and £23 for the sale of certain buildings.’ This gives us an insight into the wealth of the priory and some of its features, such as gardens and orchards.

Fairbank notes how some small vestiges of the Priory were still visible above ground in the late nineteenth-century. These have completely disappeared with later developments, and the whole area is now part of a modern shopping precinct. Interestingly, he also mentions that excavations that had taken place around the time he was writing his article for the Yorkshire Journal of Archaeology had revealed a tunnel. This tunnel measured 6 ft 9 inches high and 4 ft wide and ran underneath the Priory’s land. This was not considered to be a drain due to its sizable dimensions, the fact that it was plastered, and that there were blocked ventilation shafts along its length. Instead, it was thought to be a private passageway connecting one part of the Priory to another.

Finally, before we say ‘adieu’ to Doncaster and the Carmelites, you might want to note that it was here that Henry VIII’s nobles established their headquarters for their negotiations with Robert Aske during the Pilgrimage of Grace in 1537. According to British History Online, ‘…the prior, Lawrence Coke, supported the rebellion. He was imprisoned in the Tower and in Newgate, condemned by Act of Attainder a few days before Cromwell’s fall, but pardoned on 2 October 1540’.

As so to conclude, Henry departed from Doncaster ‘on the morn’ (Monday 17 April). The Herald makes a point of listing the nobles now in Henry’s entourage including the Archbishop of York, the Bishop of Ely (also the Lord Chancellor of England), the Bishop of Exeter (also the Lord Privy Seal) and the Earls of Lincoln, Oxford, Shrewsbury and Rivers…to name but a few.

The King was headed for a behemoth of a building, one shrouded in tales of cold-blooded murder: Pontefract Castle.

THE NEXT STOP ON THE PROGRESS IS ‘PONTEFRACT’. Click here to continue on your way.

Nearby Locations of Tudor Interest:

Gainsborough Old Hall (20 miles)

A stunning medieval manor house that was once home to Lord Bourgh, Anne Boleyn’s Lord chamberlain and the first marital home of a young Katherine Parr. Also visited by Henry VIII and Catherine Howard as well as Richard III. You can read more about it here. You may want to combine this on your itinerary with a stay in Lincoln, which is a bit further south-east of Gainsborough Old Hall.

Sheffield Manor Lodge (21 miles)

The site of a once great manor house. Now only some ruins and the Turret House remains. Sheffield Manor Lodge was one of the places in which Mary was detained during her stay in England. Cardinal Thomas Wolsey also stayed here following his arrest at Cawood and fell ill. Shortly before his death at Leicester Abbey

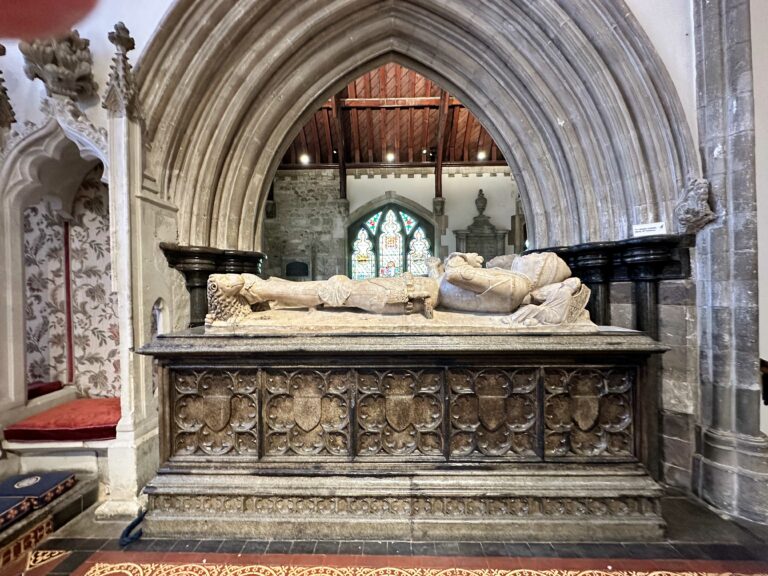

Sheffield Cathedral (23 miles)

The Shrewsbury Chantry Chapel, site of the burial of George Talbot, the 6th Earl Shrewsbury, one-time gaoler of Mary, Queen of Scots and the 4th Earl, Gaoler of Thomas Wolsey at the aforementioned Sheffield Manor Lodge

Sources and Further Reading

The Herald’s Memoir 1486-1490: Court, Ceremony and Royal Progress. Edited by Emma Cavell. 2009.

The Itinerary of John Leland in or about the years 1535-1543, by John Leland.

The Priory ‘Our Lady of Doncaster and the Carmelite Priory (1346-1538) by Tony Storey.

Friaries: The white friars of Doncaster, Pages 267-270. A History of the County of York: Volume 3, Pages 267-270. Originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1974.

The History and Antiquities of Doncaster and its Vicinity, by Edward Miller. 1804

The Carmelites of Doncaster, by F.R. Fairbank. The Yorkshire Archaeological Journal. Volume 13. 1895.

The Shrine of Our Lady of Doncaster, website of Saint Peter in Chains, Doncaster

One Comment