Cambridge, Cambridgeshire

Distance Travelled from London: 55 miles

‘[The king] rode to Waltham; and from thens the High Way to Cambrige…where he was ‘honourably received both of the university and the town’. The Herald’s Memoir

As we saw in the previous entry, the only record of Henry VII’s visit to Cambridge comes from the Herald’s account in which he writes that ‘[The king] rode to Waltham; and from thens the High Way to Cambrige…where he was ‘honourably received both of the university and the town’.

No other detail of the visit is recorded. Emma Cavell’s thesis on the 1486 progress notes that ‘bread, beer and other victuals’ provided during the King’s stay are noted in Cambridge University’s Grace Book Alpha, while payments were also made to the town’s treasurers Robert Ratheby and Richard Holmes for ‘a present given to the Lord, the king’, (Annals of Cambridge, Vol 1 p.232).

These payments confirm the Herald’s account that Henry came to Cambridge. According to Cavell, he arrived around Thursday, 16 March, although the Annals of Cambridge give this date as 12 March. While the location of Henry’s lodgings remains unspecified for this progress, as we shall see, we can gain insight into what likely transpired during this progress by looking at a later visit that Henry made to the town some 20 years later.

However, while the location of the king’s lodgings remains elusive for this section of the progress, we can postulate with a degree of confidence why the king chose to make a short diversion from the main road (Ermine Street) into Cambridge and guess a likely contender for the accommodation of the royal visitor.

As I have already mentioned, Henry was meticulous in reinforcing his image as the rightful King of England through word and deed. Since Edward IV had marched through Cambridge just ten days after his accession on his way to Pontefract, the Yorkist king and his successor, Richard III, had visited Cambridge five times in all, with the last visit by Richard coming just the year before he lost his life at the Battle of Bosworth. Cambridge had made itself worthy of Henry’s patronage on this count alone. However, his Lancastrian inheritance provided another possible motivation…

One of the notable themes of the new King’s early reign is the reverential respect paid to Henry’s late half-uncle, Henry VI: England’s previous Lancastrian King. While many of his contemporaries saw Henry VI as a weak and inept ruler, he was undoubtedly pious, and the cult of Henry VI (including, eventually, a move to have him canonised) became well-established under Henry VII. This was Tudor propaganda in overdrive and is accepted as part of Henry VII’s attempts to establish the Crown’s legitimacy under the new Tudor dynasty.

One of the notable achievements of Henry VI was to found King’s College in Cambridge. The late King had been heavily involved in the plans to build this new educational establishment. Unfortunately, due to the onset of the Wars of the Roses in the mid-fifteenth century, Henry VI had run out of money, and construction halted.

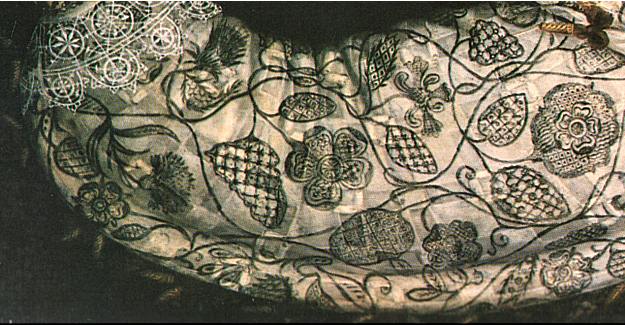

Retrospectively, we now appreciate that the founder of the Tudor dynasty eventually completed the project. However, serious progress was not made until 1508, towards the end of Henry VII’s reign, when the outer shell was finally completed. Was this notoriously parsimonious king enthusiastic in intent but not so keen to splash the cash until his coffers were overflowing? It is difficult to say, but it would be Henry’s successor, the eighth King Henry, who would oversee the completion of the project by finishing its interiors, with its piece de resistance, King’s College Chapel, being completed in 1515. If you visit today, you will see it resplendent with Tudor iconography, including the arms of Henry VII as well as the heavy oak coffer which carried the funds provided by Henry VII to continue the work on the chapel.

Yet this may not have been the only influencing factor in Henry’s visit to the town. His mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, had long been a university patron with established contacts. It is not hard to imagine her encouraging her son to visit the town. In fact, the two of them would visit together on at least two future occasions; one of these being in April 1506.

Unlike during Henry’s first visit, the King’s reception of 1506 is recorded in significantly greater detail. There is no reason to suspect that the monarch’s reception 20 years earlier differed significantly since it aligns well with other recorded royal visits to notable towns and cities.

In this account, we hear that the mayor and his brethren rode three miles out of the town, no doubt to meet the King at the limits of the city boundary. The sheriff of the shire was also present. Reforming the procession, the King approached the city. Just a quarter a mile outside of the university the ‘freres’ (friars) waited to greet their monarch, along with the ‘graduates, after their degrees and all in their habits’. Still on horseback, Henry kissed the crosses belonging to each of the four religious houses before eventually dismounting and kneeling upon a cushion ‘as accustomed’ (BTW This indicates how this was indeed part of the usual ritual of royal receptions at the time. This certainly persisted at least into the reign of Henry VIII, where we see the exact same customs being played out, for example, during the king’s visit to Canterbury in 1520 and Gloucester in 1535).

By that time, John Fisher, whose life would come to dominate court affairs during the King’s Great Matter of the 1530s, was Chancellor of the University (as well as personal confessor to Margaret Beaufort). He performed a religious ceremony in which he ‘senys’d’ the King before greeting him, most likely with a Latin oration. Afterwards, Henry remounted his horse and made his way through the town, by Blackfriars, before heading to his lodging at Queens’ College.

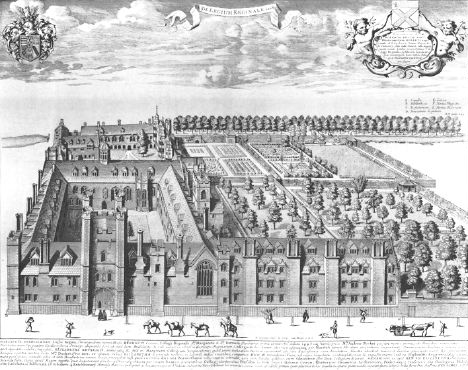

Now, this latter point is interesting. Queens’ was originally founded by Margaret of Anjou, wife and consort of Henry VI (there’s that name again!). After the fall of the House of Lancaster, Elizabeth Woodville refounded the college. (Hence, interestingly, it is called Queens’ College and not Queen’s College). Thus, this college had Lancastrian, as well as Yorkist connections, was well-established by 1486 and has what I call ‘form,’ i.e. it was deemed suitable to host one of Henry’s subsequent visits. Given these facts, I do wonder whether Queens’ was where Henry VII lodged on this first progress. I daresay we will never know for sure, but it is a tantalising possibility.

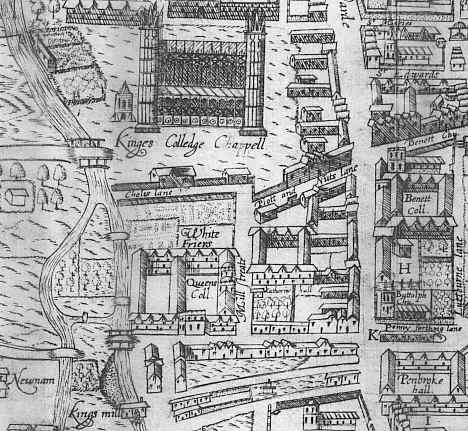

The 1506 account states that Henry rested for an hour in his lodgings at the college. However, since it was Garter Day (22 April) there was no time for idle pleasure. The King soon donned his Garter Robes and, accompanied by other Knights of the Garter, went to King’s College Chapel. This was likely just a short processional walk from the King’s lodgings in Queens’ College; early maps of Cambridge show the chapel lying directly opposite the latter college. There, John Fisher led the ‘Divine service both the Even, the Day, both at Matins etc. and the Service of Requiem on the morrow’.

Of course, as I have just mentioned, the chapel was incomplete at the time, and according to King’s College website, the service was ‘held in the first five bays of the Chapel, which had a timber roof but no stone ceiling vaults. The open end was boarded up and decorated with the coats of arms of the Knights of the Garter painted on paper’.

The only other fragment of information we have of the 1486 progress comes once again from the accounts recorded in Cambridge University’s Grace Book A when in the same breath as talking about the location of bread and other victuals for the King, it also refers to the acquisition of rolls and wax (‘scriptura rotularum et cera’). Presumably, some business was being transacted, and the King wished there to be a record of it.

Henry likely headed north-west from Cambridge towards the Great North Road, travelling via Huntingdon and Stamford toward the first major destination on the progress. The ancient city of Lincoln, standing proud atop a lofty plateau, awaited England’s new monarch.

THE NEXT STOP ON THE PROGRESS IS ‘LINCOLN’. Click here to continue on your way.

Other Nearby Tudor Locations of Interest:

Buckden Towers: (26 Miles) Buckden Palace (as it was known in the sixteenth century) was the penultimate place that Katherine of Aragon was banished to after her exile from the court in the summer of 1531. It would be the scene of Katherine’s last defiant stand, which I write about in my blog: Buckden Palace & the Most Obstinate Woman That May Be. Today, it is a Christian retreat center, and while not open to the public, there are tours by the Friends of Buckden Towers, or if you phone ahead, you may be permitted to wander around the grounds.

Kimbolton Castle: (31 Miles) Following her stay at Buckden, Katherine was eventually transferred to Kimbolton Castle, which saw her final demise in January 1536. Today, Kimbolton is a prestigious private school, so it is not open to the public except on specific open days. If you wish to read more about this location, check out my blog: Kimbolton Castle: The Final Days and Death of Katherine of Aragon.

Peterborough Cathedral: (44 Miles) A visit to Peterborough Cathedral allows you to complete your journey in the footsteps of Katherine of Aragon, as this is where the Queen was laid to rest. You can visit the place of her burial. Just check there are no services of closure that might preclude entry to the church. You can read more about the cathedral via my blog.

Sources and Additional reading:

The Herald’s Memoir 1486-1490: Court, Ceremony and Royal Progress. Edited by Emma Cavell. 2009.

The Itinerary of John Leland in or about the years 1535-1543, by John Leland.

Grace Book Alpha, containing the proctors’ accounts and other records of the University of Cambridge for the years 1454-1488 by University of Cambridge; Leathes, Stanley Mordaunt, 1861-1938; Cambridge Antiquarian Society (Cambridge, England).

Annals of Cambridge, Vol 1, by Charles Henry Cooper. 1842.