Tudor Plum Tart: The Irresistible Sweetness of Summer

As summer here in England begins to draw to an end, we have one final chance to savour one of its fleshy delights: the plum. In this month’s Great Tudor Bake Off, Brigitte Webster, from TudorExperience.com takes us through the Tudor history of the plum and shows us how to bake a Tudor plum tart. If you want to see a demo of how to make one, then be sure to read to the end and follow the YouTube link! It’s over to Brigitte…

A Short History of Tudor Plums

Last month, I thought I was going to do Tudor salads for August. However, all my salad herbs have died during the last few, extremely hot and dry weeks and so, keeping it still authentic and seasonal, we are going to spotlight plums today and how to use them to bake a Tudor plum tart.

Too much rain, or too little, would have been a very familiar problem for people in the sixteenth-century, but when one crop failed, another one was used in its place.

The earliest known data of plums locates them in China, circa 470 BC. The European plum (Prunus domestica) is believed to have been discovered around two thousand years ago in Eastern Europe, or the Caucasus Mountains, near the Caspian Sea. Others say that the plum was carried to Western Europe by the Duke of Anjou as he returned from Jerusalem at the close of the 5th Crusade (1198-1204). Either way, we know that in ancient Rome, already 300 varieties were mentioned.

Plums were one of the first fruits to be domesticated by humans. Wild plums flourished in hedgerows throughout the Old World. The domestic plum that we eat today is descended from numerous sources. The plum is closely related to the apricot, peach, cherry and even the almond.

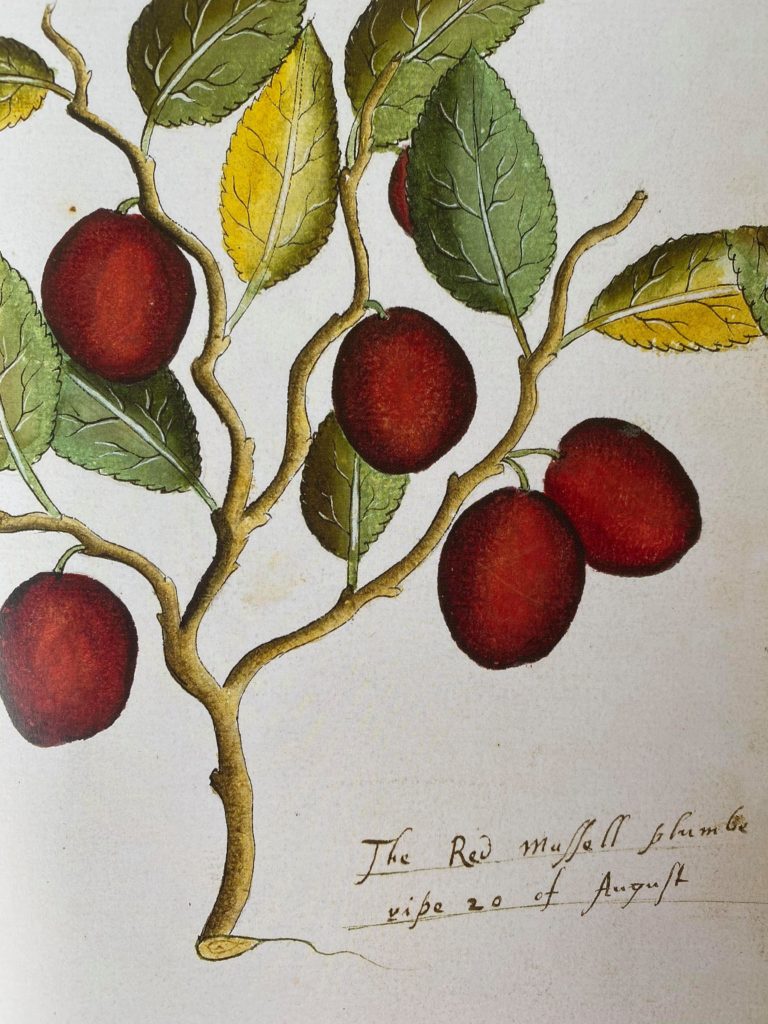

The name “plum” is derived from Old English “plume”. At the Bodleian Library in Oxford, the MS Ashmole 1504 contains a picture of a plum tree dating to the early 1500s.

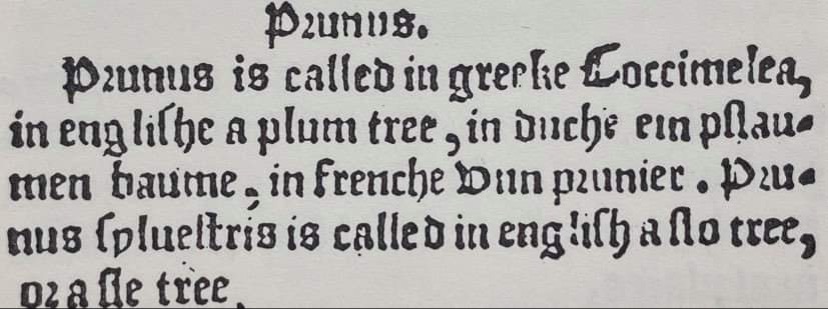

In 1548 William Turner has to say this about the plum in his “ The names of Herbes” : “Prunus is called in greeke Coccimelea, in English a plum tree, in duche ein pslaumen baume, in frenche Vun prunier. Prunus syluestris is called in English a slo tree, or a sle tree”

The plum, and its sister the ‘gage’, appear in a wide range of colours from dark purple, red, green or golden and are sweet and juicy. Traditionally they have been eaten fresh. Dried damson plums are often referred to as “prunes”.

The French elevated the status of the plum in the sixteenth-century by establishing trade with England for two of their own varieties: the damask prune, a sweet kind that was dried and sold at the grocers.

Plums were also eaten by the sailors on the Mary Rose, which sank in July 1545. About 100 plum stones were recovered from the shipwreck.

Plums make occasional appearances in upper-class cookery books of the sixteenth-century in form of fruit mousses, tarts and pies.

To English physicians, the plum was a cold and moist fruit that hindered digestion. They tended to recommend the plum as a laxative. Italian food writer Giacomo Castelvetro, however, tells us that they are healthy to eat – better fresh than dried – and advises that they are better eaten during meals, not afterwards, as the English do. His earlier countryman Platina (1463-65) states that the use of plums before a meal, if it is moderate, moves the bowels, tempers the bile and offers pleasure to the thirsty. He also recommends to pickle and store them in honey, making sure they don’t touch each other.

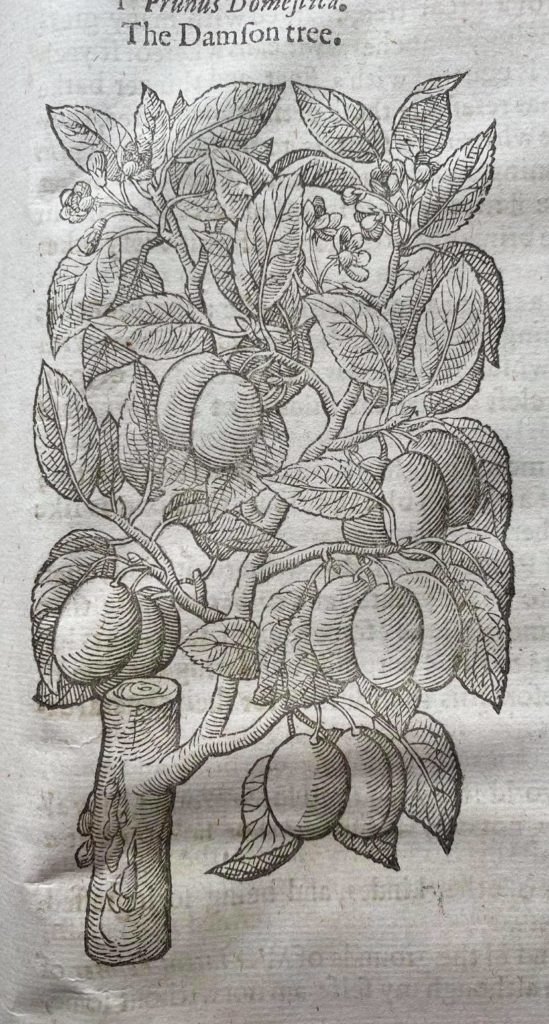

The Elizabethan herbalist, John Gerard, was proud to have over 60 different plum verities, some very rare, in his London garden. In his 1597/1633 ‘Herbal’, he mentions that the wild plum grows in most hedges. He, like his fellow contemporaries, confirms that they ‘moisten and cool’ but ‘yield unto the body very little nourishment and the same nothing good at all’. Gerard bemoans that they rot very quickly and that the plum’s juice putrefies in the body. He prefers the dried variety and believes the prunes to be more healthy.

Serious cultivation of plum varieties did not start until the seventeenth-century – John Tradescant being one of the first to actively do so.

The ‘damson’ is a subspecies of the plum and thought to have reached Europe from Damascus in Syria in pre-Christian times. It was introduced to England by the Romans. Damson stones have been found in York dating to the late Anglo-Saxon period.

Damsons are smaller, ovoid in shape, and generally less sweet than plums. They are also much hardier and generally used for cooking. These trees were used in orchards to protect less hardy ones and historically, they were the only plum planted commercially north of Norfolk. The majority of damsons are dark blue to purple in colour, but there are some now very rare forms (mentioned in 1620s sources),of white damson with green or yellow-green skin.

Damsons were a popular gift from the people of the home-counties for their king/queen. They were gathered in the wild and delivered to the royal palaces.

Shakespeare refers to damson prunes in at least 4 plays. In Henry IV, act III, sc 3, Falstaff says, ‘There’s no more faith in thee than in a stewed prune’. Prunes are sometimes associated with brothels, declined in popularity in the sixteenth-century in favour of raisins.

Types of Plums Used in Tudor Cooking

The Mirabelle or cherry plum is a cultivar group of the plum and is identified by its small, oval shape and its red or dark yellow colour.

The Bullace is another variety of the plum and often referred to as the wild plum, small and round in shape. Bullaces can be blue, purple, red, yellow or green in colour and ripen up to six weeks later in the year (October-November). It is possible, that the bullace is genuinely native to Great Britain. In Tudor England, the bullace was cultivated and familiar to many gardens but they gradually fell out of favour as larger and sweeter types emerged. The black bullace is the common wild one found in the woods, the white bullace has small yellowish fruit with greenish flesh. A very old one by the name of ‘cricksies’ probably originating in Anglo-Saxon ‘creke’ was grown in large quantities in Norfolk in the nineteenth-century. Bullaces are generally only used for fruit preserves.

The tart bullace was an import from France known as the ‘pruneola’; dried and stones removed, it was packed in little wooden boxes and sold as banqueting treats.

Another cousin of the plum is the Sloe, the fruit of the blackthorn which we will look at later in the year.

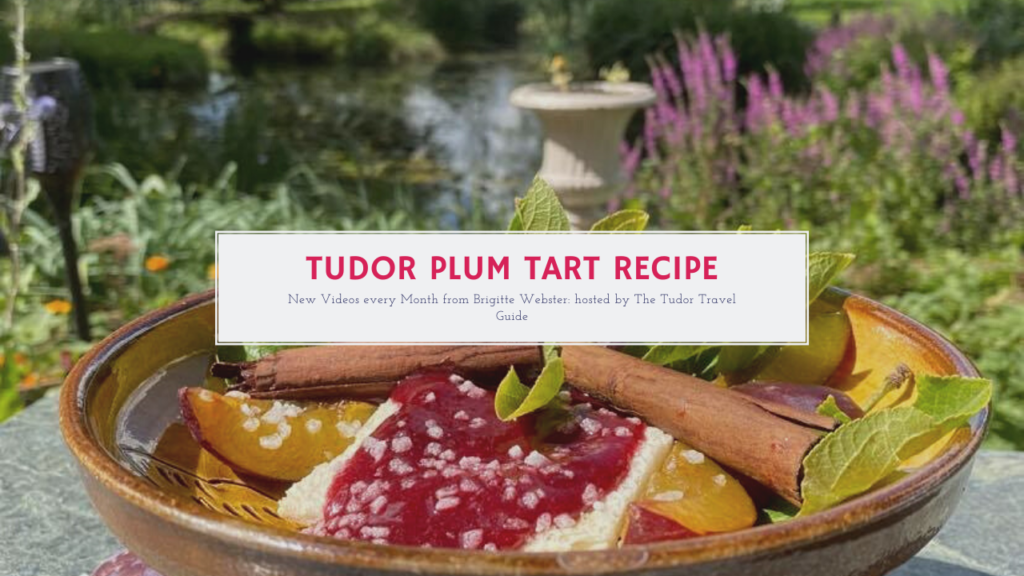

To Make a Tudor Plum Tart…

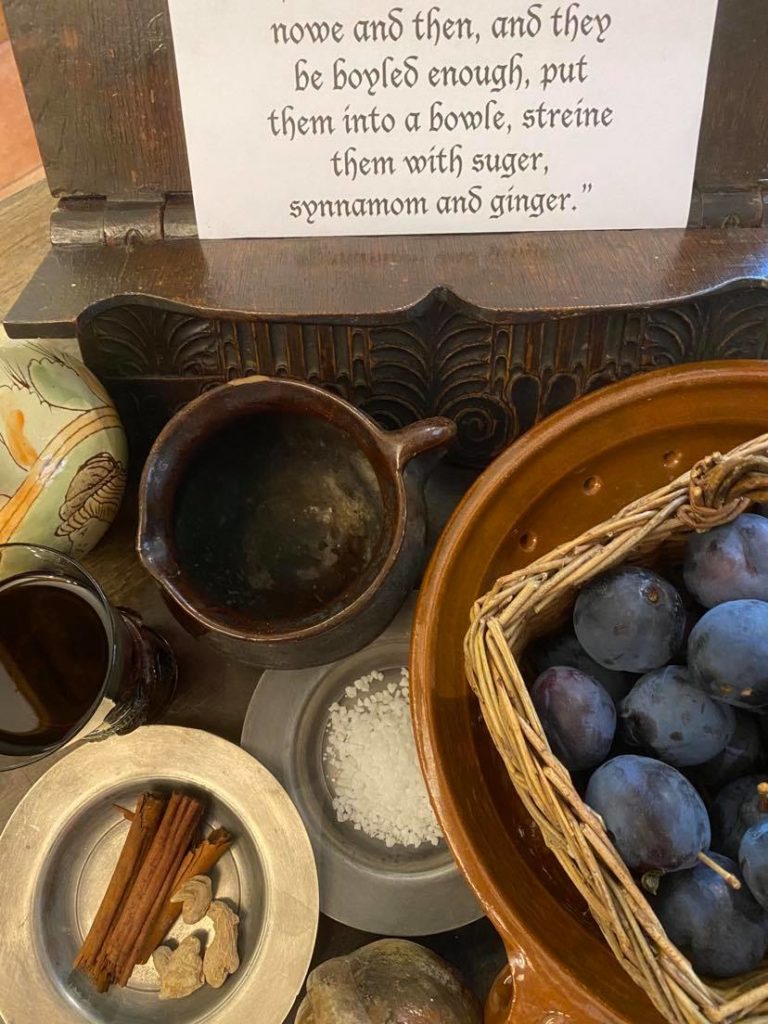

‘Put your prunes into a pot and put red wine or claret wine, and a little fair water. Stir them now and then, and they be boiled enough, put them into a bowl. Strain them with sugar, cinnamon and ginger.’

Modern interpretation :

To make a Tudor plum tart, first cook your washed & de-stoned plums in the red wine ( with a small amount of extra water if you are using dried prunes) until soft. Strain mixture through a colander or use food blender for a smoother texture. Add the very fine sugar and cinnamon & ginger to your taste.

Serve it hot or cold as a fruit mousse or as a toast topper.

The Tudors were rather suspicious of eating raw fruit and the plum with its “cold & moist” properties needed hot & dry spices (cinnamon & ginger and sugar) to balance that. The fact, that the plum was cooked would also have helped, in their mind, to make this dish healthy.

This recipe does not clarify HOW to use this fruit filling in a tart. You could either make a blind-baked shortcrust pie (similar recipes using fruit paste in this way appear in the same cookery book) or use a ready-made one. Another possibility, following Bartolomeo Scappi’s instructions (1570) is, to serve it on a ‘sop’ which is a kind of toasted, sliced white bread. This is the variety I have gone for and provides a lovely healthy breakfast!

Ingredients to make a Tudor Plum Tart : (circa 4 people)

Circa 170-200g plums/damsons or prunes

Stick of cinnamon (or ground)

1 cup of red wine

2-4 tbsp sugar

circa 2tbsp fresh chopped ginger (frozen or less if ground)

Optional:

Slice of white bread, toasted or fried in olive oil

Or

Shortcrust pie – made yourself or bought.

Watch Brigitte Make a Tudor Plum Tart…

To watch Brigitte make this recipe in her kitchen at the Old Hall in Norfolk, click on the image below:

About Brigitte…

Each month, our Tudor recipe is contributed by Brigitte Webster. Brigitte runs the ‘Tudor and 17th Century Experience‘. She turned her passion for early English history into a business and opened a living history guesthouse, where people step back in time and totally immerse themselves in Tudor history by sleeping in Tudor beds, eating and drinking authentic, Tudor recipes. She also provides her guests with Tudor entertainment. She loves re-creating Tudor food and gardens and researching Tudor furniture.

Each month, our Tudor recipe is contributed by Brigitte Webster. Brigitte runs the ‘Tudor and 17th Century Experience‘. She turned her passion for early English history into a business and opened a living history guesthouse, where people step back in time and totally immerse themselves in Tudor history by sleeping in Tudor beds, eating and drinking authentic, Tudor recipes. She also provides her guests with Tudor entertainment. She loves re-creating Tudor food and gardens and researching Tudor furniture.

Sources & further reading:

Food in Modern England, by Joan Thirsk

Food in medieval times, by Melitta Weiss Adamson

Food in Early Modern Europe, by Ken Albala

The fruit, herbs & Vegetables of Italy – Giacomo Castelvetro (1614)

On Right Pleasure and Good Health – Platina (translated by Mary Ella Milham)

Botanical Shakespeare, by Gerit Quealy

The names of Herbes, by William Turner 1548

The Generall Historie of Plantes, John Gerard, 1597/1633

Flowers and Trees of Tudor England, by Clare Purnam

Thank you for this in depth and informative article. Such research takes a great deal of time and effort. My neighbour’s plum tree was barren this year. Sadly yeilding not one dingle plum. Hoping for a return to a rebirth of plenty next season.

I am sure Brigitte will appreciate your comment. Here’s hoping for more plums next year!

Brigitte–I enjoyed your presentation on the history of the plum very much. I also loved the section where you took us in your kitchen to cook the plum tart. It’s so much fun watching your videos. They are so educational as well as enjoyable to watch. You obviously research your subject well. As a side note–I made your “Spicy Tudor Bread” in ” my kitchen” and it turned out very well. My husband ate more than one slice after trying it!