Ludlow Castle: The Playground of Princes

Ludlow Castle: Blog Updated in March 2025.

Ludlow Castle and the Tragic Death of Prince Arthur Tudor

In March 2025, I visited Ludlow Castle to record an on-location episode of The Tudor History & Travel Show, commemorating the anniversary of the premature death of Arthur Tudor, Prince of Wales. He died at Ludlow on 2 April 1502, aged 15.

Arthur Tudor (1486–1502) was the eldest son of King Henry VII and Elizabeth of York and the older brother of the future King Henry VIII. His birth united the warring Houses of Lancaster and York, but his early death changed the course of English history forever.

Arthur was heir to the English throne and given the title ‘Prince of Wales’. Following a tradition established by the Yorkist king, Edward IV, Arthur was sent to Ludlow at the age of 7 in 1493 to learn the art of kingship as titular head of the Council of the Marches.

At 13 years old, Arthur was married by proxy at nearby Tickenhill Palace to Katherine of Aragon, the Spanish princess and youngest daughter of King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I. Two years later, Katherine arrived in England, and the couple were married shortly thereafter amidst an extravagant celebration at the gothic St Paul’s Cathedral in London. After their marriage, Arthur returned to Ludlow with his new bride at his side. Yet, after just five months, Arthur fell gravely ill and died – probably from some acute infectious disease such as the dreaded Sweat.

With Arthur gone, his younger brother Henry (the future Henry VIII) became heir. As we know, Henry later married Katherine of Aragon, Arthur’s widow. The failure of the marriage to produce a living male heir eventually led to the break from the Catholic Church and the creation of the Church of England, as the King sought to annul their marriage and take Anne Boleyn as his new bride.

Below is a blog written a few years ago exploring the history of Ludlow Castle as a location associated with Princess Mary, who, as Princess of Wales, followed in her uncle’s footsteps by spending time at Ludlow. In updating this write-up, I have added a link to the aforementioned podcast below and a gallery of accompanying images taken during my recent visit.

Note: This episode is the first of a two-part series following the story of Arthur’s time at Ludlow, his precipitous and untimely death there in April 1502, and his body’s subsequent transfer to Worcester Cathedral for burial. You can listen to the first part of the series here or by clicking the button below. If you wish to read a more fulsome account of the history of Ludlow Castle or Princess Mary’s association with the town and its castle, scroll down to read the entire blog…

Listen to the Podcast Here

Ludlow Castle: Mortimer’s Majestic Power-Base in the Marches

Ludlow Castle was built by the de Lacy family shortly after the conquest. It is an imposing structure, which is perched on a rocky promontory overlooking the River Teme. It is described by the eminent architectural historian Antony Emery as ‘arguably one of the finest Edwardian residences in England – and by ‘Edwardian’, he means Edward I!

However, the castle was to truly reach its zenith under the ownership of the power-hungry Roger Mortimer, who, having affiliated himself with the estranged wife of Edward II, Isabella of France, essentially seized power in England and became king in all but name. Ludlow was the epicentre of his power base during that period, and Mortimer held court at Ludlow. It became ‘a semi-royal centre with much feasting, entertaining, and a procession of friends and guests’.

As a wealthy magnate, Mortimer was responsible for adding to the castle’s existing great hall and lower chamber block; he commissioned the construction of an extensive and palatial second residential (or ‘Upper’) chamber block, as well as the Chapel of St Peter. We will learn more about these apartments in a moment, but suffice to say at this stage that, according to Emery, the result was to create a ‘magnificent group of buildings’, which were an ‘outstanding example of [their] time’ and that ‘its only peer [was] the great hall, service and residential range added at Kenilworth Castle at the close of the fourteenth century’.

Ludlow Castle as a Training Ground for Kingship

In the fifteenth century, as Earl of March, a young Edward Plantagenet inherited the property from his father. So, on his accession to the throne as Edward IV in 1461, Ludlow Castle became the property of the Crown. When Edward sent his own sons to live there, away from London’s foul air and machinations, a precedent was set. For three generations, Ludlow Castle was to become the principal seat of first, ‘The Prince’s Council’, then later ‘The Council of the Marches’, through which the Prince and/or Princess of Wales presided over their own mini-court and kingdom; a sort of training ground for princes!

Image © The Tudor Travel Guide.

Accordingly, Prince Arthur, the eldest son of Henry VII, resided at Ludlow with his council from the age of seven. He returned to govern the Marches as Prince of Wales with his new bride, Katherine of Aragon, in January 1502. Of course, their joy and triumph were short-lived when Arthur died on Saturday, 2 April, in the same year, only months after their marriage. Goodness only knows what Katherine was thinking and feeling as her entourage eventually left Ludlow, and she wound her way back to London with an uncertain future! I suspect she wouldn’t have dreamt that 24 years later, her 9-year-old daughter by her first husband’s younger brother would follow in her footsteps and hold her own court at Ludlow Castle as Princess of Wales!

The Royal Apartments at Ludlow Castle

Any royal party arriving at Ludlow Castle would have had to make its way gradually uphill through the town, across the bustling marketplace, no doubt thronged with curious onlookers, and then on under the twelfth-century gatehouse. This formed the principal entrance to the castle, as it does today, allowing access to the vast outer bailey. Occupying an area of almost four acres and surrounded by the castle’s curtain wall, this expansive space housed stables, storehouses, and workshops.

Image © The Tudor Travel Guide.

As usual, the inner bailey contained the privy apartments at the castle. It was reached by passing from the outer bailey through an arched entrance next to the original Norman keep. Once through this second gateway, the residential lodgings were directly opposite, built along the curved curtain wall. Begun in the late thirteenth and completed in the fourteenth century, these high-status buildings were palace-like in their magnificence and comprised a series of interconnected buildings. From left to right, these included a three-story solar block which extended into the northwest Norman tower, an adjoining Closet Tower; in the centre, a magnificent great hall, which in 1684 was said to be ‘very fair’ and, to the right, another three-story residential block, sometimes referred to as ‘The Great Chamber Block, or Upper Chamber Block’.

The principal rooms used by the most high-status residents were on the upper storey of the Solar Block, accessed directly from the adjacent great hall by a spiral staircase or by a staircase on the ground floor. Prince Arthur had occupied these lodgings during his sojourn at the castle, and we might surmise that Princess Mary had done the same. Perhaps Mary had heard tales of her mother’s time in Ludlow from Katherine herself or from her governess, Margaret, Countess of Salisbury (who had also accompanied the 15-year Katherine to Ludlow in 1502). One wonders how she felt about being at the place where her beloved mother had experienced such elation, as well as such sadness.

Image © The Tudor Travel Guide.

Today, the apartments are an empty shell; the roofs and floors are gone, although they did survive into the nineteenth century. The exposed stone walls, some covered in moss and lichen, look bleak, and it is hard to see how Ludlow Castle could be viewed as palatial. However, it most certainly was in its day; the configuration of rooms into private suites heralded the latest in residential fashion for the aristocracy of the medieval period. And so, today’s time-traveller must reimagine its splendour; the walls plastered, covered in the rich hues of finely carved oak panelling, with expensive tapestries hung thereabouts, the chambers warmed, and brought to life by the flames dancing in the hearths of the many open fireplaces.

The Nineteenth Month Progress of Princess Mary

In 1525, final preparations were being made for Princess Mary to take up her position as titular head of a new ‘Council of the Marches’; a position last formally held by her long dead uncle, Arthur. The orders of Henry VIII stated that ‘the good order quiet and tranquilitie of the Countreyes thereabout hath greatlie bene alterd and subverted’ by the absence of royal authority. A new council was required to reassert royal power in the region. Mary was now nine years old; as Henry VIII’s only surviving heir, she was now old enough, it seems, to begin her grooming for kingship; she would gain valuable experience in how to conduct herself during ceremonial occasions. Thus Mary, the king’s ‘deerest most beloved onely doughter’, would go to Ludlow with a council and hold court there.

But what of Mary Tudor’s sojourn at Ludlow? According to Princess Mary’s Itinerary in the Marches of Wales 1525-1527: a Provisional Record by W.R.B Robinson, many historians have inaccurately surmised that much of the Princess Mary’s itinerary, after she left the court to take up residence in the Marches, was spent at Ludlow. Robinson points out that this summation is primarily based on a lack of scrutiny of contemporary records, particularly the Journal of Prior More of Worcester, and the misdating of certain letters included in The Letters and Papers of Henry VIII. This re-evaluation of the documents leaves us with a much more complete (although there are still gaps in the records), and accurate, itinerary in which we see the princess effectively go on a greatly extended progress.

So, what do we know of this itinerary? Well, having taken leave of Wolsey at his house of The More, in Hertfordshire, on 12 August 1525, the royal party moved to Tewkesbury via Wooburn (Woburn), Reading Abbey, Malmesbury Abbey, Kingswood Abbey, Thornbury Castle, and Gloucester. Mary seems to have effectively based herself at Tewkesbury between September and the following January (notwithstanding the occasional trip to Worcester), where she was lodged in a manor in the park belonging to the abbey.

Probably just after Twelfth Night (6 January) 1526, the princess finally moved on from Tewkesbury, relocating to Worcester and the surrounding area (as a guest of Prior More) until mid-April, when she travelled to Hartlebury, some 25 miles to the east of Ludlow. The princess eventually arrived in Ludlow in early May. However, we should be clear that the evidence for Mary’s presence there is indirect and comes via two letters sent by John Veysey, President of Mary’s Council and Bishop of Exeter. These letters were dispatched to Lord Ferrers at Westminster with instructions to show them to the king and Wolsey. The latter had largely overseen the assimilation of the Princess’ Council.

The first of these letters, dated 3 May, concerns the potential jeopardy facing Mary. There were concerns for her life as the plague had broken out in ‘ dyvers townes and palces yn thes partes’. Veysey goes on to state his dilemma that ‘if any suche ynfeccion [infection] should fortune to be at Hartalbury [Hartlebury] [we] have not hereabout any place convenyent wherunto the princes grace may remove to.’, (i.e. if plague broke out at the nearby manor of Hartlebury, they were scuppered(!), with nowhere safe to retreat that was both away from the crowds and suitable to house a royal princess).

There is no direct evidence that Mary was there; therefore, the conclusion is by inference, and it is two-fold. Firstly, in this letter, Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury, Mary’s ‘lady governess’, is specifically mentioned as being present at the castle. The reasonable hypothesis, therefore, is that Mary’s governess was unlikely to be anywhere other than at the princess’ side.

Secondly, one of the concerns was that those councillors who had been in contact with ‘suitors’ (‘suitors’ meaning people travelling from the surrounding areas to pay homage to Mary or to petition the young princess) should be kept away from the princess for fear of passing on any infection. As the council was also at Ludlow Castle at the time, this would seem to be an odd request if Mary was already safely housed elsewhere.

The desire was to protect the precious Tudor heir to the throne at all costs. Orders were promptly dispatched from London, via Wolsey, to remove Mary ‘to be logid aparte in sum convenient place, standing in clene aier with a [convenient?] nombr about her’. This duly ensued, ‘with her noble grace beyng withdrawen with privy company in a place solitary, bycause of the deth [plague] for introduction of the French tongue’. Where this ‘place solitary’ was is unknown, but the Tudor Princess remained lodged there through part of May and into June.

Image © The Tudor Travel Guide.

But how would Mary have spent her time at the castle? Clearly, she was expected to participate in certain ceremonies; such participation would teach Mary what was expected of her royal role. Outside of this, her religion and studies must have taken up much of her time. She had, of course, been brought up steeped in her Catholic faith and was as devoted to her religious practice as her mother. The princess likely tended to her devotions daily. When not in the chapel, she was most likely with her tutors or spending time with her female companions, learning the pursuits befitting a royal lady, such as sewing, reading, dancing, and playing musical instruments. On Sundays and Holy Days, prayers and services were held in the Norman chapel of St Mary Magdalene, situated in the inner bailey; it is hard to imagine Mary being absent during these occasions.

Interestingly, after this point in Mary’s story, contemporary documents suggest that she began to wend her way back through Worcestershire and Oxfordshire to meet up with the king and queen at the Old Palace of Langley, a satellite hunting lodge of nearby Woodstock Palace. Mary spent a month at court with her parents on progress, visiting places like Stony Stratford and Ampthill. Afterwards, they parted once more, with the princess heading back out towards Worcestershire, where she spent Christmas and the following two months at Bewdley, most likely at the Tudor mansion called Tickenhill House.

By late February 1527, Mary had arrived back in London. The king had recalled her so she could be presented to the French Ambassadors, who were there to negotiate her betrothal to Francis I. However, the political climate was changing quickly – and not to Mary’s advantage. When the princess set out for Ludlow in the summer of 1525, she could not have seen how her world was about to be rent apart by ‘The King’s Great Matter’. Yet, when she returned it is likely that her father was already head over heels in love with Anne Boleyn; most historians date the beginning of this romance to 1526/27. Mary’s legitimacy would soon come into question in the quest for a legitimate son. By early 1528, the council was disbanded permanently; never again would Mary preside over her father’s dominions in the Marches as Princess of Wales.

Note of Gratitude: My thanks go to my co-author, Natalie Grueninger, who wrote the original entry for Ludlow Castle in In the Footsteps of the Six Wives of Henry VIII, and some of whose facts and words I have used in the writing of this blog.

Image Gallery: Ludlow Castle

The images below were taken during my on-location visit to Ludlow in March 2025.

Image © The Tudor Travel Guide.

Image © The Tudor Travel Guide.

Inside the inner bailey.

Images © The Tudor Travel Guide.

Sarah and Norico in the ruins of (left) the privy apartments most likely used by Prince Arthur and Mary Tudor, and (right) the great hall of Ludlow Castle.

Image © The Tudor Travel Guide.

Images © The Tudor Travel Guide.

Image © The Tudor Travel Guide.

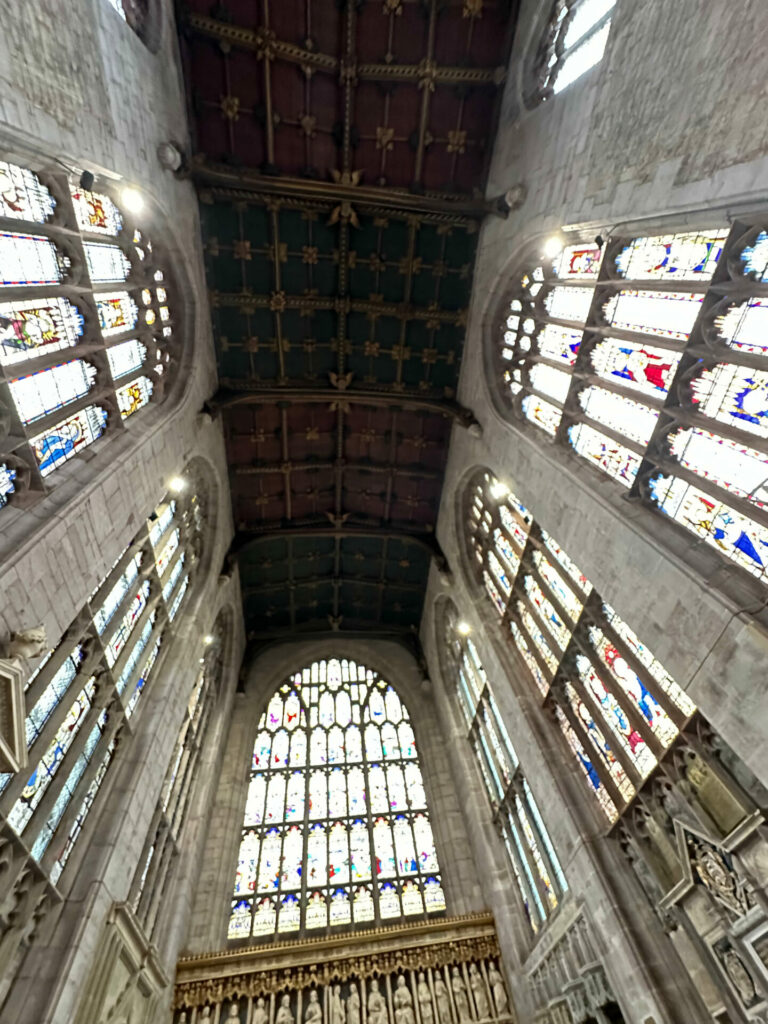

Inside St Laurence’s Church, Ludlow.

Images © The Tudor Travel Guide.

Sarah inside St Laurence’s Church, Ludlow, where the heart of Prince Arthur is buried in the chancel.

Images © The Tudor Travel Guide.

Useful Links

Visiting information for Ludlow Castle is here.

To listen to the second episode in this podcast series commemorating Arthur Tudor, click here. The accompanying show notes are here.

To read more about Arthur Tudor’s tomb, click here.

Here is a show notes page accompanying this on-location podcast from Worcester Cathedral. To commemorate the anniversary of the premature death of Arthur Tudor, Prince of Wales, I have recorded a two-part podcast series. In this episode, Part II, I follow the story of Arthur’s body’s transfer to Worcester Cathedral for burial.

Wonderful informative article.

Thank you so much!

A very interesting article. I have visited Ludlow several times but didn’t know about the connection to Mary.

Thank you…To be honest, neither did I? But there is always something new to be learned, I find : )

Hi Sarah, this is a great source of information, thank you! I was wondering if it is possible to still get a copy of ‘PRINCESS MARY’S ITINERARY: 1525-1527’ at all please? It would really help with some research I’m doing and when I try to subscribe to receive it I am just getting an error message. Thank you.

Hi Keren! Email me and I will be able to send it to you. S