The 1535 Progress: The Vyne, Hampshire

The King and Queen came to my poor house on Friday the 15th of this month, and continued there till Tuesday.

William, Lord Sandys to Thomas Cromwell, written from the Vyne, 22 October.

The Vyne and the 1535 Progress: Key Facts

– Anne Boleyn visited the Vyne on two occasions: in August 1531 and again in October 1535.

-It is possible that Anne conceived for the final time at the Vyne.

– Built on the site of a medieval house, the Vyne was a grand moated manor house, possibly even rivalling Hampton Court Palace in size.

The Tudor chapel is mainly unaltered, as is the stained glass in the east window, said to be among the finest examples of painted glass of the Renaissance period in England.

On Friday, October 15 1535, Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn arrived at the Vyne, the home of William, Lord Sandys, one of Henry’s leading courtiers and Lord Chamberlain of the Royal Household. This was not Anne’s first visit to the house, as she had been by Henry’s side when the court spent at least two days there in August 1531; however, it was her first sojourn as Queen.

As stated in the Introduction to the 1535 Progress, it is possible that Anne conceived for the final time at the Vyne. There is a suggestion that this child was the much-longed-for son Henry and Anne desperately wanted. Had he lived, he would have become heir to the Tudor throne and almost certainly saved his mother and uncle from the horrors of the scaffold.

But on this crisp autumnal day, the future would only have yawned brightly for Anne as she returned to The Vyne, trotting on horseback through medieval parks and formal gardens as the royal retinue approached the grand moated house. Described by Leland in c.1542 as ‘one of the Principale Houses in all Hamptonshire,’ in its heyday, the Vyne possibly even rivalled Hampton Court Palace in size. It was rebuilt primarily of brick on the site of a medieval house, with much of the work carried out between 1524 and 1526, and consisted of multiple ranges that made up a series of courtyards. In this palatial house, surrounded by acres of lush greenery, Sandys entertained his monarchs and the court for four days.

Anne and Henry were provided with their own suites of rooms on the first floor, which were connected by a gallery and may have been arranged around a courtyard. A complete inventory of the Vyne taken after Lord Sandys’ death in February 1541 describes the contents of some sixty rooms, including: ‘the king’s chamber’, ‘the Quenys grete chamber’, ‘the Quenys lying Chamber’ and ‘quenes pallet Chamber’.

Interestingly, the Queen’s rooms appear to have been more richly furnished than the King’s. As there exists no evidence of any subsequent visits by Henry VIII, it can be safely assumed that these rooms were appointed for Henry and Anne’s visit. They were presumably occupied later on by Sandys and his wife, Margery, as the inventory records no other rooms for them in the house. However, We should be mindful that the rooms were recorded as they were found more than five years after the royal visit, so some of the contents may have changed. Nonetheless, it paints a vivid picture of the level of luxury to which Anne and Henry were accustomed.

The Queen’s great chamber was a riot of colour and texture, dominated by a bed of green and crimson velvet, dressed in a valance fringed with silk and a gold and red satin quilt. There were also eight fine tapestries, a black velvet chair, four red and yellow satin curtains, a large pair of andirons (metal stands for holding logs in a fireplace) and a gilded ‘loking glass’. In her ‘lying Chamber’ were found, among other items, five tapestries, a bed of cloth of gold and russet velvet with a matching valance fringed with silk and gold, a quilt of russet and yellow satin, two curtains and a medium-sized pair of andirons. The King’s chamber had five small hangings, a pair of andirons, a green velvet bed and matching valance fringed with silk and gold. To the modern eye, such interiors might have appeared garish, but this was the height of opulence to the Tudor observer.

The Queen’s lodgings were followed by ‘a great dining chamber’, which served as the ‘chief ceremonial room’. There, Anne and Henry spent time with their hosts and courtiers, eating and drinking, and, as described in a letter by Francis Bryan to Thomas Cromwell on the day of their departure, being ‘mery’.

The walls were decorated with panelled or painted plaster and lined with nine magnificent hangings, the floor covered with the most expensive Turkish carpet in the house. The furniture included one chair of black velvet, trimmed and garnished with gold, a large table, a pair of trestles and a cupboard. In addition, cushions of varying sizes appear in large quantities, with more than forty recorded! Some were made of crimson velvet, others of red and blue damask and a dozen cushions described as ‘very sore worn’ depicting roses and pomegranates—a device adopted by Katherine of Aragon—perhaps these were stored by the hosts during Anne’s visit…

Moving further east through additional first-floor chambers, Anne would have arrived at the closets for Lord and Lady Sandys, ‘over’ and ‘next’ to the chapel, respectively. Both closets were furnished with ‘hangings of great flowers with my lord’s arms in the garter’ and were used to hear Mass privately while the rest of the household stood in the body of the chapel below. Outside those found in royal palaces, it was one of the most lavish private chapels of its time, richly appointed with embroidered altar cloths, hangings and vestments for a priest, a deacon and a sub-deacon.

In the base court, there were many other rooms that were relatively comfortably furnished and presumably used to accommodate members of the court. Also recorded in the inventory are stables and kitchens, rooms for the schoolmaster, yeomen and cooks and an armoury where there was kept ‘a pavilion conteyning iii chambers and a hall new with all their appurtenances’. Such pavilions were used for ceremonial or military purposes, as seen at the Field of Cloth of Gold. However, they were probably also erected to supplement a house’s permanent accommodation and may have been used to house some of Anne and Henry’s entourage during their stay.

As was the fate of so many grand Tudor houses, the Vyne was drastically reduced in size, altered, and modernised by subsequent owners. Thus, much of Lord Sandys’ house lies today buried beneath the lawns north of the present house. Only a few of the sixty or so rooms included in the 1541 inventory survive.

Among the most extraordinary is a richly decorated first-floor oak gallery, almost certainly part of the gallery recorded in the inventory as connecting Anne and Henry’s rooms and one of only a handful of long galleries surviving from the early sixteenth century.

At the time of Anne’s visit, it was sparsely furnished and, unlike most other rooms in the house, contained no hangings. The showpiece was the exquisite floor-to-ceiling linenfold panelling installed between 1518 and 1526, which still lines the walls today. Sandys had the coat of arms of many of his contemporaries carved into the panelling, creating a Who’s Who of early sixteenth-century Tudor England. Keen eyes will notice, among other devices, the pomegranate and castle of Katherine of Aragon’ the TW initials and cardinal’s hat for Thomas Wolsey, and Sandys’ own coat of arms and insignia, including a ragged cross, the initials WS, a winged half-goat and his badge of a rose merging with a sun.

The panelling was painted in the early nineteenth century, and some years later, the bay window at the south end of the gallery was added. Before leaving, take note of the carving of the royal arms supported by cherubs above the east door, as it is believed to mark the entrance to Henry’s suite of rooms.

Next, you come to a space currently occupied by the Gallery Bedroom and South Bedroom. If you could travel back in time to 15 October 1535, you would find yourself standing in Henry’s lodgings, where gentlemen of his privy chamber, like Sir Francis Bryan, who we know was present on this occasion, kept the King company, dressed and undressed him and performed a variety of other tasks. Sadly, nothing remains of the rooms where Anne once held court, although we can get an idea of the panelling that would have lined the walls in her chambers by visiting the Dining Parlour on the ground floor.

Although not original to the room, the linenfold panelling is Tudor. The room is also home to a number of interesting paintings, including a beautiful portrait of Chrysogona Baker, Lady Dacre, aged six, and a portrait of Charles Brandon after Hans Holbein. Mary Neville, Lady Dacre, and Henry VIII can also be found among the sea of faces.

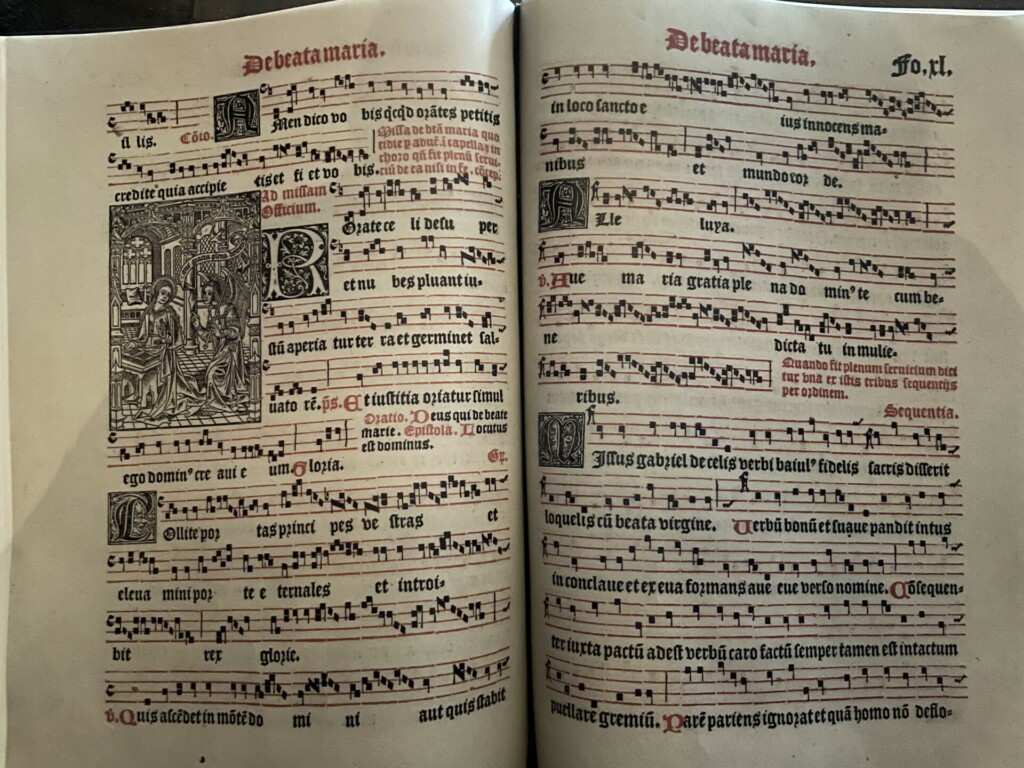

The final remarkable survival of Sandys’ Tudor mansion is the magnificent chapel. Although the Ante-Chapel is a separate room today, it formed part of the chapel in the sixteenth century. Most of the interior decoration is of a later date. However, there are a few important exceptions; the beautifully carved choir stalls are Tudor and largely unaltered, as is the stained glass in the east window, among the finest examples of painted glass of the Renaissance period in England.

On the top row is depicted The Passion of Christ, and on the bottom row, left to right, Queen Katherine of Aragon kneeling with St Catherine, Henry VIII, shown at about thirty years of age with his name saint, St Henry of Bavaria and finally, Queen Margaret of Scotland, Henry’s sister, with St Margaret of Antioch. Sandys originally commissioned the glass for the Chapel of the Holy Ghost in Basingstoke, where he and Margery were later buried. They were probably moved to the Vyne during the Civil War. At the time of Anne’s visit, the window was probably glazed with some form of heraldic glass.

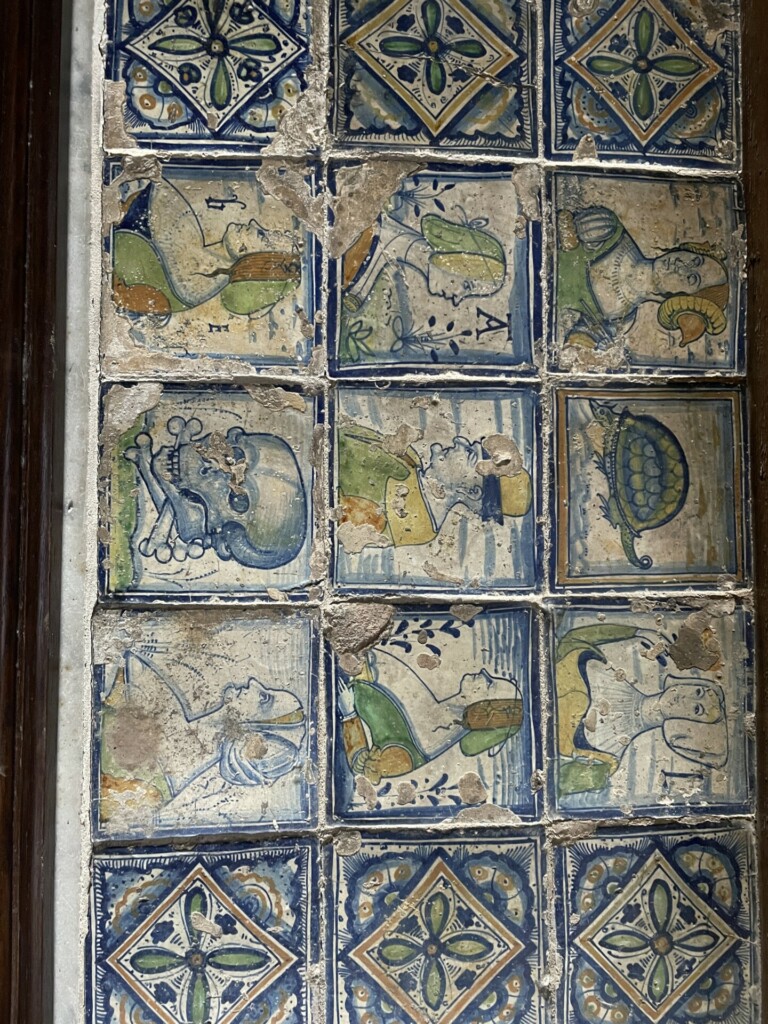

The exquisite chapel tiles were imported from Antwerp in the early sixteenth century but only moved to their present position in the nineteenth century. They are glazed in four different colours: lemon yellow, cobalt blue, orange and bright green, a luxury only available to the wealthiest in Tudor times, and are striking to behold. Similar tiles were ordered for Hampton Court Palace and The More, Cardinal Wolsey’s manor house in Hertfordshire. However, It remains unclear whether Anne saw them during her visit, as they were only first recorded in the chapel in the eighteenth century.

The surviving interior features of Lord Sandys’ Tudor house are a potent reminder of a time when the Vyne was one of the grandest houses in Hampshire and Queen Anne Boleyn, possibly in the first bloom of pregnancy, still hopeful of living up to her motto—The Most Happy.

Visitor Information

The Vyne is managed by the National Trust. For more information on how to reach The Vyne and its opening hours, which are seasonal, visit the National Trust website here or call + 44 (0) 1256 883858.

To listen to the podcast associated with this blog click here.

The next stop on the progress is Basing House, click here to continue.

To join Sarah at The Vyne in Hampshire, to hear the story of its Tudor history and the momentous visit made by Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, click here.