KATHERINE PARR, QUEEN OF ENGLAND

Name and Title: Katherine Parr (she signed her letters Kateryn Parr), Queen of England.

Born: Blackfriars, London, c.1512.

Died: 5 September 1548.

Buried: Sudeley Castle Chapel, Winchcombe, Gloucestershire.

Katherine was most likely born in London, circa 1512, at the Parr family townhouse in Blackfriars, sited north of the Thames and close to the city’s western edge. Her father, Sir Thomas Parr, was in service to the young Henry VIII as Comptroller to the King and High Sheriff of Northamptonshire. Through his maternal line, Thomas could claim direct lineage from King Edward III of England via the omnipotent John of Gaunt. At the same time, the family had deep ties to two great families that dominated the political scene of the previous century: the Nevilles and the Beauforts.

Although the family’s ancestral seat was at Kendal Castle in Westmoreland, by the early sixteenth century, the castle was in decay, and most historians agree that Katherine’s parents, who were both in royal service at the time, would have been staying in London when Katherine, the eldest of three children was born. It is thought likely that she was named in honour of Henry’s queen consort, Katherine of Aragon, in whose household, Katherine’s Mother, Maud, served as Lady-in-Waiting.

Sadly, Katherine’s father died when she was just five years old, leaving the family to be brought up under the watchful eye of their 25-year-old mother at Rye House, in Hertfordshire, a fragment of which still survives and can be visited today. The foundations of Katherine’s formidable humanist education would be laid down in the schoolroom at Rye. She eventually became proficient in French, Latin, and Italian and took up Spanish once she was queen. She was also the first woman to publish a work of literature under her own name – albeit after the death of her third husband, King Henry VIII.

Katherine Parr: Wife and Widow

Katherine’s marital career started in 1529 when she was still a teenager. Katherine was seventeen when she was contracted to become the wife of Edward Borough, the twenty-year-old son and heir of Sir Thomas Borough of Gainsborough in Lincolnshire. Her new home was to be Gainsborough Old Hall, where the irascible Sir Thomas, Lord Chamberlain to Anne Boleyn, ruled the house with an iron fist.

In 1531, the young couple eventually set up their own household in the nearby village of Kirton-in-Lindsay. However, at some point before April 1533, Edward died, leaving Katherine as a widow for the first time but not the last.

At this point, Katherine was in her early 20s. Perhaps to mourn and take stock, she subsequently moved to the household of her aunt (through marriage), Catherine Neville, at Seizergh Castle, close to her family’s ancestral home in Kendal. While staying at Seizergh, Katherine was introduced to her second husband, John Neville, 3rd Lord Latimer. Considerably older than Katherine, he brought with him two children from a previous marriage; one of them, Margaret, would remain a close companion of the queen-to-be until her stepdaughter died in 1546.

Now Lady Latimer, Katherine’s new marital home was Snape Castle near Leyburn, North Yorkshire. She was in residence at Snape when the flames of the northern revolution known as The Pilgrimage of Grace took hold across Lincolnshire and Yorkshire in 1536/37. That winter, the rebels besieged the family home at Snape, taking Katherine and the two children hostage as surety of Lord Latimer’s hasty return from London – and a pledge of his support for the cause, which targeted the close advisors of the king, notably Thomas Cromwell.

Lord Latimer hurried home, and whatever assurances he gave the rebels, somehow, order was returned, and Katherine and her two step-children were released unharmed. Although the Crown’s confidence in Latmier was shaken, John Neville also emerged relatively unscathed. It had been a fine and dangerous line to navigate, and the shock of the fallout may well have informed the family’s subsequent move south, to the less ‘brute and beastly’ county of Northamptonshire, where Katherine had long-standing family connections.

In 1543, John Neville died at the couple’s London home on Charterhouse Square, and not long after, Katherine came to the attention of the King. It is unclear exactly when or how this happened and why Henry Tudor chose Katherine as his sixth wife. However, it is clear from Katherine’s extant letters that although her heart lay elsewhere (with Thomas Seymour, it would later transpire), she willingly submitted to the King’s will, marrying Henry VIII at Hampton Court Palace on 12 July 1543.

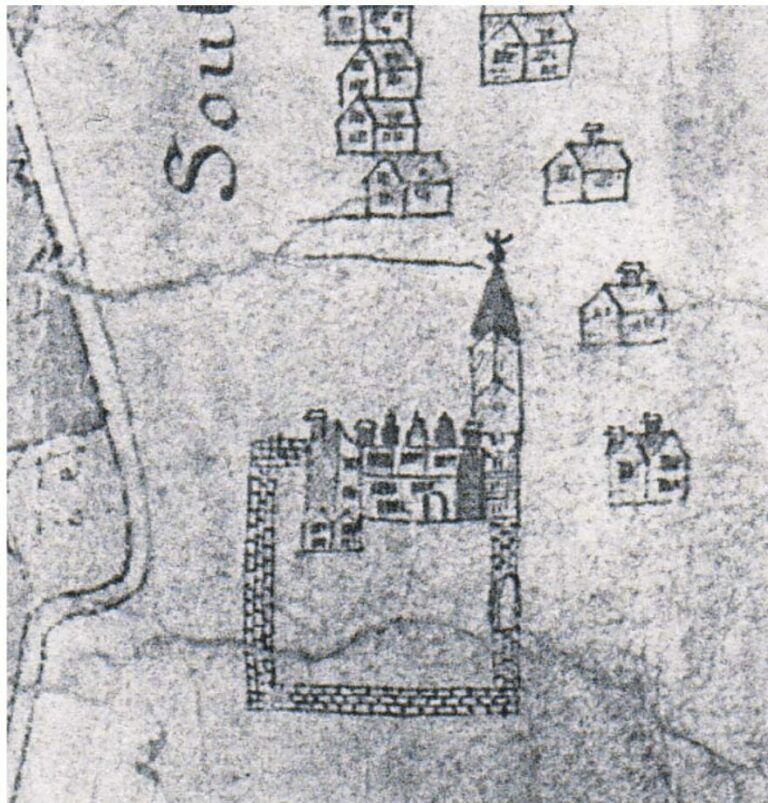

Image: ©The Tudor Travel Guide

Astute, learned and deeply pious, by this time, Katherine had forsaken her Catholic upbringing and was an ardent devotee of the Reformed Faith. This made her a target for the conservative Catholic faction at court, where her religious inclinations brought her close to ruin. A plot to have the Queen arrested was thwarted only by Katherine being forwarned of the arrest warrant drawn up against her, and her quick thinking, which appealed directly to the King’s vanity and underlined her natural subservience as a wife, a woman and a loyal subject.

Henry VIII died on 28 January 1547, leaving Katherine a widow for the third time. Now a mature and wealthy woman of independent means, the Queen Dowager, this time, looked for love, following her heart to Thomas Seymour’s door. The pair started a clandestine affair while Katherine was in residence at Chelsea Manor. At some point, they wed, with Katherine falling pregnant soon after.

In Spring 1548, Thomas moved his new bride away from the filth and press of the city, to his idyllic Gloucestershire home of Sudeley Castle. There, Katherine whiled away her pregnancy accompanied by the young Princess Elizabeth (who was devoted to her stepmother) and Thomas Seymour’s ward, Lady Jane Grey. Although Elizabeth fell foul of some rather questionable behaviour on Seymour’s part and was sent away to protect all those concerned, Lady Jane was present when the Dowager Queen went into labour.

Image: ©The Tudor Travel Guide

On 30 August 1548, Katherine was delivered of her first child, a girl named Mary. Tragically, the former died of puerperal fever five days later, on 5 September. Having been embalmed, the late Queen was laid to rest on 7 September in what is believed to have been the first Protestant funeral in England to be held in English. Miles Coverdale took the service, while Lady Jane Grey acted as chief mourner. Seymour had already left for London.

The Burial of Katherine Parr

The following is a contemporary account of the burial entitled, ‘A Breviate of the Internment of the lady Katherine Parr, Queen Dowager, late wife to King Henry VIII, and after, wife to Sir Thomas, Lord Seymour of Sudeley, and High Admiral of England. The extract is taken from ‘Katherine Parr: Complete Works and Correspondence’ edited by Janel Mueller.

‘Item – On Wednesday, the fifth of September, between two and three of the clock in the morning, died the aforesaid lady, late Queen Dowager, at the castle of Sudeley in Gloucestershire, 1548, and lieth buried in the chapel of the said castle.

Item – She was cered and chested in lead accordingly, and so remained in her privy chamber until things were in a readiness.

Hereafter followeth the provision in the chapel.

Item – It was hanged with black cloth garnished with escutcheons of marriages viz. King Henry VIII and her in pale, under the crown; her own in lozenge, under the crown; also the arms of the Lord Admiral and hers in pale, without crown.

Items – Rails covered with black cloth for the mourners to sit in, with stools and cushions accordingly, without either hearse, majesty’s valence, or tapers – saving two tapers whereon were two escutcheons, which stood upon the corpse during the service.

The order in proceeding to the chapel.

First, two conductors in black, with black staves.

Then, gentlemen and esquires.

Then, knights.

Then, officers of houshold, with their white staves.

Then, the gentlemen ushers.

Then, Somerset Herald in the King’s coat.

Then, the corpse borne by six gentlemen in black gowns, with their hoods on their heads.

Then, eleven staff torches borne on each side by yeomen about the corpse, and at each corner a knight for assistance – four, with their hoods on their heads.

Then, the Lady Jane, daughter to the lord Marquis Dorset, chief mourner, led by a estate, her train borne up by a young lady.

Then, six other lady mourners, two and two.

Then, all ladies and gentlewomen, two and two.

Then yeomen, three and three in a rank.

Then, all other following.

The manner of the service in the church.

Item – When the corpse was set within the rails, and the mourners placed, the whole choir began, and sung certain Psalms in English, and read three lessons. And after the third lesson the mourners, according to their degrees and as it is accustomed, offered into the alms-box. And when they had all done, all other, as gentlemen or gentlewomen, that would.

The offering done, Doctor Coverdale, the Queen’s almoner, began his sermon, which was very good and godly. And in one place thereof, he took a occasion to declare unto the people how that there should none there think, say, nor spread abroad that the offering which was there done, was done anything to profit the dead, but for the poor only. And also the lights which were carried and stood about the corpse were for the honor of the person, and for none other intent nor purpose. And so went through with his sermon, and made a godly prayer. And the whole church answered, and prayed the same with him in the end. The sermon done, the corpse was buried, during which time the choir sung Te Deum in English.

And this done, after dinner the mourners and the rest that would, returned homeward again. All which aforesaid was done in a morning.’

The Tomb of Katherine Parr

Following the English Civil War, in the first half of the seventeenth century, when Royalists had held Sudeley Castle against Parliamentarian forces, many of its roofs were removed deliberately to sleigth the building. This allowed the weather to begin its exorable work of reducing the sumptuous state apartments and chapel to ruins. As a result, Katherine’s body was ‘lost’ for the next 200 years. The story of her rediscovery and the shocking desecration of Katherine’s corpse can be read in detail here. It is certainly worth a read, for rarely, if ever, has a royal corpse been subjected to such despicable behaviour.

However, with the original Tudor monument destroyed, it was left to the Victorian owner of Sudeley, Emma Dent Brocklehurst, to commission a replacement. This was to be designed by the celebrated English Architect, Sir George Gilbert Scott. At the same time, John Birnie Philip remodelled Katherine’s effigy. The arms of her four husbands are depicted on the front of the tomb’s chest.

Finally, once the remodelling of the chapel was complete, in 1861, the Queen’s body was reinterred in the church’s crypt, where she has lain in peaceful repose ever since.

Does anything remain of the original tomb? Broken fragments of the original Tudor monument survive. One piece, which appears to be of the lower half of Katherine’s gown, is displayed in the castle’s permanent exhibition, along with several items taken from the corpse over the centuries. These include a tooth and a lock of hair, which are shown in the images below.

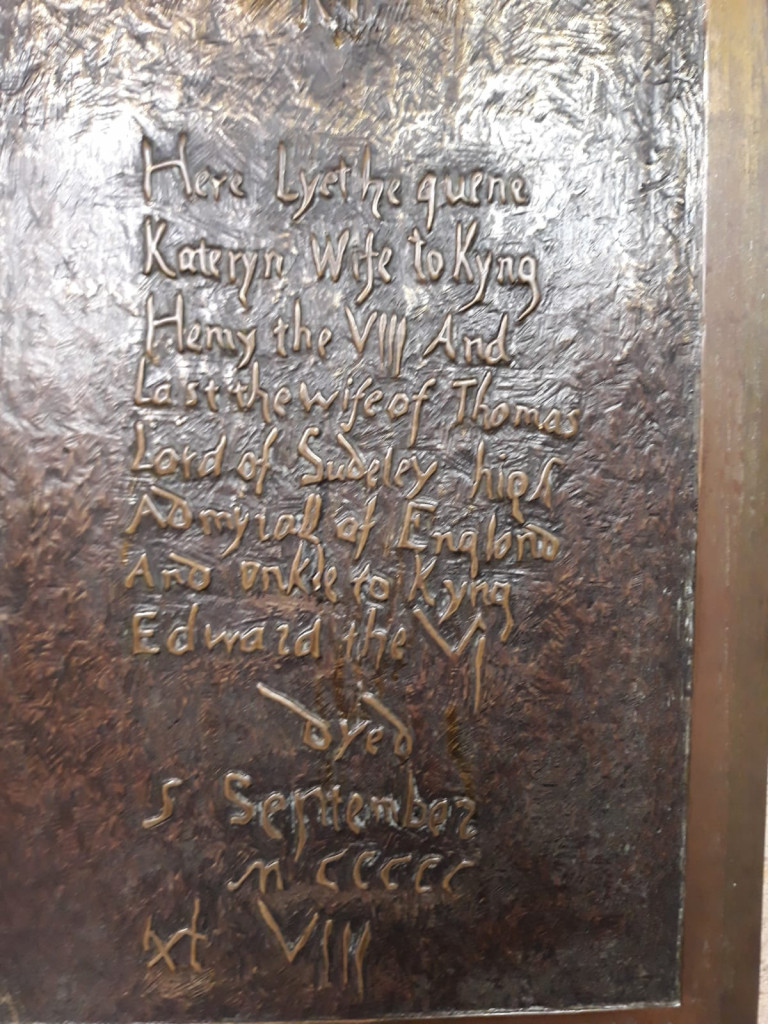

Upon the lid of the led coffin in which Katherine’s body had been sealed were the words:

KP. Here lyeth Queen Katheryne Wife to Kinge Henry the VIII and The wife of Thomas Lord of Sudely high Admy… of Englond And ynkle to Kyng Edward VI.

These have been reproduced and are fixed next to the wall of Katherine’s romanticised monument.

Visitor Information

To find out the latest opening times for Sudeley Castle (which are seasonal), check out the visitor information on their website.

If you wish to stay nearby in Sudeley Castle’s holiday cottages, check this out.

Other Locations Nearby

3 Miles: Hailes Abbey is a ruined Cistercian Abbey and was one of the first religious houses inspected by Cromwell men’s men as part of the ‘visitations’. It was possibly visited by Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn while staying at Sudeley Castle during the 1535 progress.

17 Miles: Gloucester: Visited by Henry VII and Elizabeth of York during the 1502 progress and later the base used by Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn to explore the surrounding countryside during the 1535 progress. Locations of interest are Gloucester Cathedral, Llantony Secunda Priory, Blackfriars, Brockworth Court (occasionally open during Heritage Open Days in September), Painswick Church (burial site of Sir William Kingston) and Prinknash Abbey (cafe and chapel only). For a complete write-up of the 1535 progress, check out In the Footsteps of Anne Boleyn on Amazon, or signed copies can be purchased through my shop.