Edmund Tudor, 1st Earl of Richmond (also known as Edmund of Hadham)

Name and Title: Edmund Tudor, 1st Earl of Richmond

Born: 1430

Died: 1 November 1456

Buried: Greyfrairs, Carmarthen, Carmarthenshire and later reburied in St David’s Cathedral, Pembrokeshire

Edmund Tudor, father to King Henry VII of England, was born about 1430 at Much Hadam Palace, Hertfordshire. It was a palace owned by the then Bishops of London. He was the elder of two sons born to their mother, Katherine of Valois, the widow of Henry V, and their father, Owen Tudor. Tudor was a member of an aristocratic and influential family from North Wales.

Through their mother, Edmund and Jasper were half-brothers to King Henry VI of England, who was around nine years their elder. Following their mother’s death in 1437, the two boys were placed in the care of Katherine de la Pole, the abbess of Barking Abbey, who herself was of aristocratic lineage, being the daughter of the 2nd Earl of Suffolk and sister to the Duke of Norfolk.

Due to Katherine’s influence, by 1442, their half-brother, the King, had begun to take an interest in the two boys, welcoming them at court. Edmund and Jasper became advisors to Henry VI as they grew to their majority. They were his closest blood relatives and were granted titles and lands, with Edmund Tudor becoming the 1st Earl of Richmond in November 1452.

The brothers were close to their half-sibling and were legitimised by an Act of Parliament in March 1453, receiving recognition as the King’s true and legitimate brothers.

Edmund Tudor’s military allegiances are a little tricky to untangle, as despite being a Lancastrian, during the Wars of the Roses, for periods of time, he supported Richard of York (father to the future Kings Edward IV and Richard III).

Richard moved to secure the Regency of England during the 17 months in which Henry VI first suffered incapacitating mental illness, with Edmund supporting his cause in direct opposition to the will of Henry VI’s wife, Margaret of Anjou, who wanted the Regency for herself.

As King Henry VI lapsed between health and mental illness crises, the sands of power constantly shifted. This made for a tricky and sometimes dangerous scenario for the brothers, who had to negotiate the changing tide. However, for much of the time, the Tudor brothers seemed to retain the confidence of both Yorkist and Lancastrian houses and were never stripped of their titles.

Amidst this, on 1 November 1455, Edmund married his twelve-year-old ward, Margaret Beaufort, the only daughter of John Beaufort, 1st Duke of Somerset, at her family home of Bletsoe Castle.

At the time, she was one of the wealthiest heiresses in England. Henry VI had encouraged her mother, the Dowager Duchess of Somerset, to bring the then ten-year-old to court and seems to have facilitated the match with his half-brother. Margaret was descended from royal English blood through John of Gaunt and Katherine Swynford. As the King had no children at the time of the match, it is possible that he was considering the potential of any child from the union to be an acceptable heir to the Lancastrian throne.

Although considered young, even for the time, the marriage was consummated immediately, and subsequently, the couple moved to Lamphey Palace (the country palace of the Bishops of St David’s) in Pembrokeshire. It is believed by many biographers of Henry VII that the king-to-be was conceived at Lamphey in the late Spring of 1456.

Meanwhile, Edmund’s orders from Richard of York were to put down a local rebellion led by Gruffydd ap Nicholas. This he did soundly, retaking key castles in South Wales, including Aberystwyth, Carmarthen, Kidwelly and Carreg Cennen.

Yet, due to an (as it would turn out) unfortunate turn of events for Edmund, Henry VI had once more regained the reigns of power and deposed Richard of York. In retaliation, the York faction sent 2000 men to take back South Wales under the leadership of William Herbert (of Raglan Castle). Herbert seized Carmarthen Castle, and Edmund Tudor, who it is said, was thrown into the dungeon there.

Edmund Tudor died shortly thereafter, aged 26, on 1 November 1456 (not the 3rd as is often said – see my discussion of Edmund’s tomb below). The official cause of death was the plague. However, rumours have always abounded that he was, at worst, murdered by the York loyalists (as he was a serious contender for the Lancastrian throne and therefore best removed from the picture) and, at best, sorely neglected or mistreated. A murder trial was even held a few months after Edmund’s death, but no party was convicted. However, modern biographers of Henry VII, including Nathan Amin, feel that foul play can certainly not be ruled out.

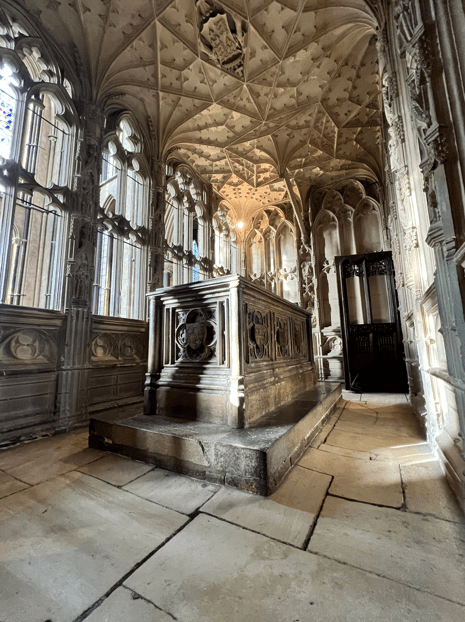

Edmund’s body was initially buried in the Franciscan church of the Greyfriars in Carmarthen. His son, Henry VII, would later build a fine tomb for his father. However, in 1539, after the friary was dissolved, Henry VIII had his grandfather’s remains relocated directly in front of the high altar in St David’s Cathedral, where they remain.

The Tomb of Edmund Tudor

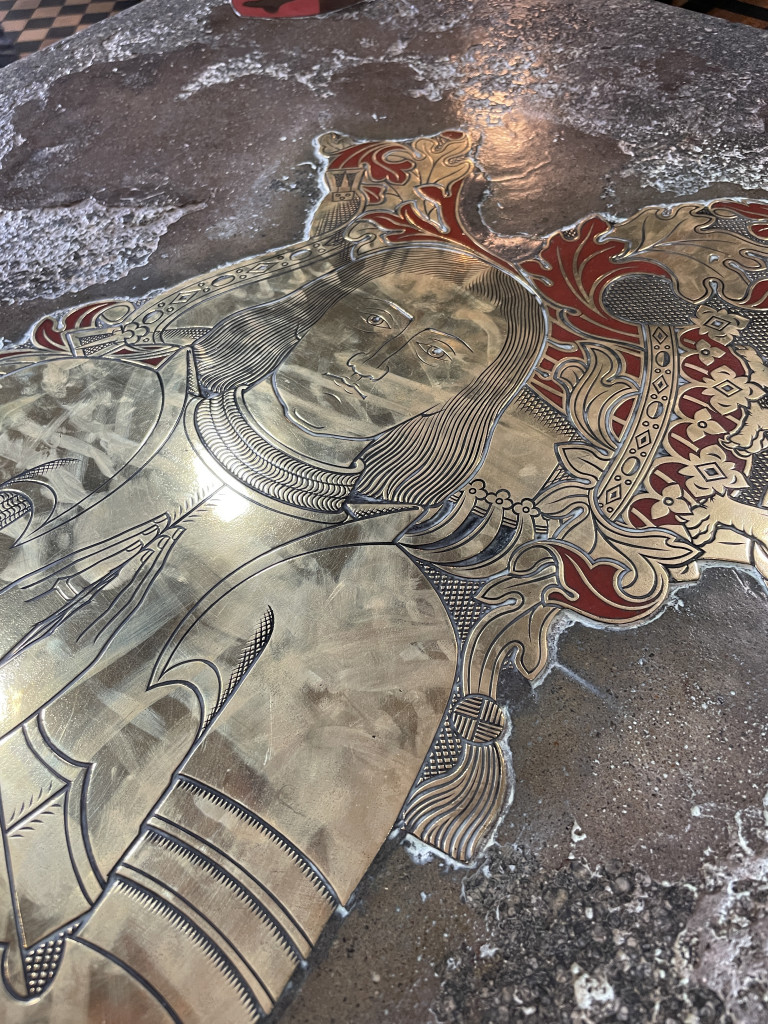

Edmund Tudor’s simple chest tomb stands directly before the high altar in the fabulous St David’s Cathedral in North Pembrokeshire. It is fashioned from Purbeck marble, and a Victorian brass of Edmund, dressed in armour, has replaced the original. The red dragon of Cadwaladr sits close to his left shoulder.

However, around the edge of the lid, an inscription reads:

‘Under this marble stone here interred rest the bones of that noble lord Edmund, Earl Richmond, father and brother to kings, the which departed out of this world in the year of our Lord God 1456, the first day of the month of November on whose soul Almighty Jesu have mercy. Amen.’

This is a genuine Tudor inscription in Gothic lettering but written in English (which would not have been the case at the time of Edmund’s death). Between each word is a Tudor rose in an act of immaculate sixteenth-century branding!

When I was at St David’s recently, interviewing its librarian and curator, Mari James, she pointed out that the lettering that denotes the 1st of the month looks more like ‘3rd’. She highlighted that many sources mistakenly state that Edmund died on 3 November and that although we simply don’t know when the Earl died, we DO know that on the tomb, the Tudors have recorded the date as 1 November.

Finally, Mari also confirmed that at some point in the past, bones have been seen in the tomb and that there is no vault under the cathedral. Thus, Edmund’s remains seem interred above ground, within the stone chest.

Visitor Information:

St David’s is the smallest city in the United Kingdom, and not only does it live up to its name, it is utterly charming! Its tiny market square with coffee shops and the occasional artisanal boutique is complemented by its abundance of historical riches. Notably, this includes the cathedral and the adjacent Bishop’s palace, which lies in ruins – although these ruins are substantial and definitely worth a visit. Cadw manages the palace, so expect free or reduced entry if you are a Cadw or English Heritage member.

Edmund’s tomb is easy to find, right at the heart of the most sacred space within the cathedral. Once you have lingered awhile and perhaps read the inscription for yourself, why not head into the adjacent north transept and kneel upon the cushion in front of the shrine of St David? This is an original medieval shrine (which the Tudors failed to destroy during the reformation completely), so it is quite something to see! You can experience for yourself what it would have been like to be a medieval pilgrim and pray afore the bones of St David. I encourage you to do so, and if you are travelling with someone, you will find that whatever you say within the prayer niches will not be heard by those standing nearby – it is quite a miracle of medieval soundproofing!

Also, head to the space behind the high altar, which today is a chapel but was once the pilgrim’s ambulatory. A peephole directly behind the high altar looks into the choir. As pilgrims filed past, they could see the monks and the service going on inside. This peephole was only uncovered during restoration work during the Victorian period and is decorated by original twelfth-century carved stone detailing. While standing in the same space, look up and see if you can spot the coat of arms of Henry VII with a particularly fine red Welsh dragon on display!

Other Links:

- If you want to read more about Raglan Castle, home to William Herbert and, for a while, the childhood home of Henry Tudor, click here.

- If you want to watch me talking about the history of Raglan Castle on location, follow this link.

- For more information about the early Tudors, why not try these biographies: ‘Tudor: The Family Story‘, by Leanda de Lisle or The House of Beaufort: The Bastard Line that Captured the Crown by Nathan Amin