The City Palace of Düsseldorf: The Early Years of Anne of Cleves

Our journey into the lives of Henry VIII’s six wives takes us overseas to the City Palace of Düsseldorf in the Rhine Valley, one of seventy locations detailed in my book, In The Footsteps of The Six Wives of Henry VIII. Going behind the scenes of the Tudor places that some of our most beloved historical figures called home, we discover interesting, controversial and revealing details. You can purchase the book from most online retailers. However, if you are looking for an extra special gift, then you can purchase signed copies with a personal dedication, made out to the loved one of your choice from my shop. Click here to browse and buy.

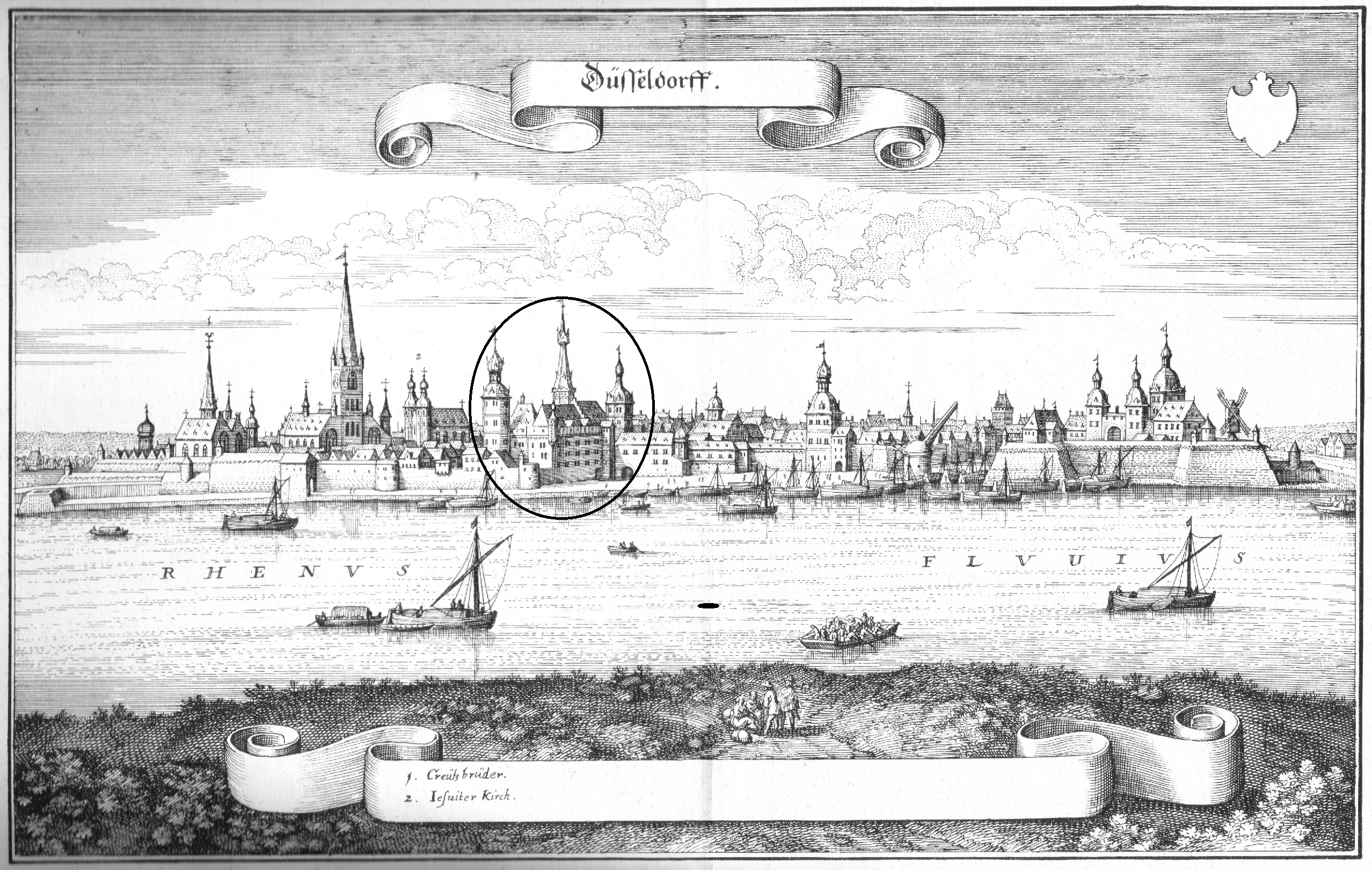

In the meantime, to get a taste of what is in the book, let’s travel back to Düsseldorf 1515 when the Duchess of Maria of Jülich-Berg gave birth to her second daughter, Anna, (hereafter referred to by her anglicised name, Anne), in the city palace. It is unclear exactly how much time Anne spent at the Ducal Palace in Düsseldorf but Anne’s early years certainly shaped her character and attitudes in later life. Let’s find out more…

Following in the Footsteps of Anne of Cleves

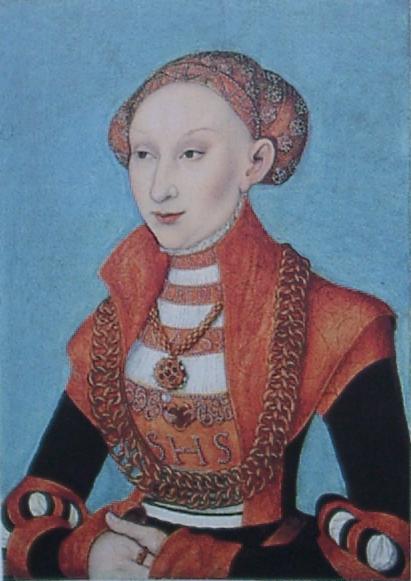

How well do you think you know Anne of Cleves? We know all about her fated first meeting with Henry VIII, her short tenure as queen and the quick divorce that followed. But what about her character? Who was Anne of Cleves and can we get just that little bit closer to knowing the woman who infamously, and rather cruelly, became widely known as the ‘Flanders Mare’? We begin our quest to understand the Princess of Cleves in her birthplace, the City Palace of Düsseldorf, and explore her early years in the ducal principality that she called home for the first twenty-four years of her life.

I am fascinated by how our early experiences shape our character. I believe that if you want to understand the lives of any of Henry’s consorts, you must first understand the forces that shaped the women during their most impressionable years.

With In the Footsteps of the Six Wives of Henry VIII, I was honoured (as it turns out) to explore the early years of Anne of Cleves, or ‘Anna von Jülich-Kleves-Berg’, to give Henry’s fourth wife her full Germanic name. I travelled to modern-day, northwest Germany, to the Rhine Valley, there to immerse myself in the palaces and castles of the long-lost ducal principality.

My aim was to conjure up once more the cultural milieu that delivered to England this woman, who the French Ambassador described at the time as being, ‘of very assured and resolute countenance’ and who in every way behaved ‘like a princess’. I was intrigued; who would I find lying behind the butt of many a historical joke?

The City Palace of Düsseldorf: The Birthplace of Anne of Cleves

The language barrier presented the first obstacle to unlocking the secrets of Anne’s heart. For someone who does not speak German, it felt like an intimidating quest. It required even more than the usual effort, this time to find those who could literally interpret the silent stories locked within the fabric of the buildings and cities that bore witness to the first twenty-four years of Anne’s life. Fulsome help from local historians, archivists, guides and translators prepared me well for my first encounter with Anne on her native, German soil.

The day itself was inauspicious; although it was the height of summer, Düsseldorf (the place of Anne’s birth) was blighted by heavy, relentless rain. Early in the morning, I made my way along the near-deserted streets of the city’s Aldstad [Old Town], a decrepit umbrella barely shielding me from the squally showers.

I quickly found myself at Anne’s birthplace, the site of the now-lost City Palace of Düsseldorf One remaining tower stands proud in the centre of Burgplatz [Castle Place], telling me that I had arrived in the right place. Here was the beginning of Anne’s strict upbringing at the ducal court.

Growing up never ‘far from her mother’s elbow’, the Duchess Maria always looked ‘straightly to her children’, raising them to live up to the values prized at the ducal court – those of modesty, subtlety, devotion to faith and purity being first amongst them. It was while researching life at the City Palace of Düsseldorf that I learnt about the extreme propriety of German court life.

For example, when Anne was nineteen, a proclamation set forth requirements for ‘daily quiet and orderliness’, with no ‘spontaneous parties’; at nine o’clock in the evening, the last glasses of wine were poured before being locked away for the night by the hofmeister [master of the palace]. After this time, ‘playing, drinking or sitting together’ by members of the court was strictly prohibited. Quite a far cry from the frivolity and decadence of the French court in which Anne Boleyn had been raised.

Next, I headed out of the city. Not far from Düsseldorf, nestled amongst the wooded hillsides of the Rhine Valley, I had my second encounter with Anne. It was here, of all the places visited in connection with the German princess, that I felt I finally broke through into her world, appreciating her with new eyes.

Schloss Burg is a fortified hunting lodge, perched imperiously atop a plateau of rock, its vistas stretching out over the lush, green forest. It is said that it was here that Anne spent a good deal of her childhood with her mother and her two sisters, Sibylle and Amelia.

I was met by a warm-hearted, generous castle guide, who had lived in Germany for well over twenty years. Extremely knowledgeable about the castle and life at the ducal court, not only did I see the rooms in which Anne would have spent much of her time, but we were able to compare and contrast the everyday life of a Renaissance noblewoman of both the English and German courts.

From a letter penned by Sir Nicolas Wooton to Henry VIII in 1539, it is well known that Anne’s main accomplishment was needlework, ‘which occupieth most of her time’, and that she [Anne] could not speak any language other than German, or…sing or play any instrument, for they take it here in Germany as a rebuke and an occasion of lightness that great ladies should be learned or have any knowledge of music.

Hunting and hawking were also frowned upon as a suitable pastime for ladies of breeding.

As I stood in the Kemenate, the main privy chamber of the castle, I felt for her; how hopelessly ill-equipped was Anne for the life of an English queen! How easy it must have been for those less generous members of Henry’s court to sneer behind her back at her lack of social accomplishments, and how little she had to share with her husband!

My guide also recounted the loving and intimate relationship between Anne’s mother and father, betrothed at the ages of five and six, respectively. Apparently, the couple were devoted, often writing letters of love. It was a practice that would be replicated by Anne’s elder sister Sibylle when she was parted from her husband during the Schmalkaldic War.

I was struck for the first time by how Anne had been brought up in a warm and loving household. She had been taught how to love with a generous heart. I saw perhaps how, even when rejected by her capricious husband after only six months of marriage, Anne’s early experience allowed her to cling to a fairytale long after it had, in reality, turned to dust.

What is certain though is that this stable, loving, family environment nurtured a kind-hearted, amiable character whose earnest wish had been to please the man who never loved her, and be accepted by a nation who seems never to have fully appreciated this woman’s many admirable qualities.

Just as a reminder, all my adventures in Anne’s homeland, including the places in which she grew up, are recounted in more detail in In the Footsteps of the Six Wives of Henry VIII. However, for now, my hope is that having read this post, you too will feel just a little bit more of a connection to this gentle soul and, as I did, appreciate afresh that in so many ways and, contrary to popular belief, Anne was indeed a beautiful woman.

One Comment