‘Palaces of Revolution’: Life, Death and Art at the Stuart Court

This post contains some affiliate links

Confession time: I am not a fan of the Stuart monarchy. In fact, if you press me, then privily I will admit that although my interest in English history stretches way back to our Anglo-Saxon forefathers, it stops around 24 March 1603 with the death of Elizabeth I, the last Tudor sovereign. In truth, there are very few people who could tempt me out of my Tudor hovel but one of them is Simon Thurley. His treatise on the palaces of Tudor England called Houses of Power: The Palaces that Shaped the Tudor World is probably my most treasured work of historical non-fiction. The detail is astounding with every word being a morsel of delight to be savoured. So, I was delighted to see the recent release of his new book: Palaces of the Revolution: Life, Death and Art at the Stuart Court – even though the focus of this book moves to the seventeenth century and the Stuart dynasty.

You might argue that this book should not be of interest to a Tudor purist like me. However, apart from the fact that Simon Thurley is the preeminent architectural historian of our age (and I do have an obsession with old buildings), there is of course overlap between these two royal houses. The Stuarts, of course, became intertwined with the bloodline of the Tudor dynasty when Margaret Tudor, daughter of Henry VII, married King James IV of Scotland in 1503. Then, 100 years later, with the death of Elizabeth, James VI of Scotland, son of Mary, Queen of Scots inherited the English Crown.

This is where Simon Thurley’s new book begins, at the Scottish court and with the proclamation of James as the new King James I of England. The palaces that James inherited south of the Scottish border had been fashioned by the previous dynasty and so, on this point, we find a happy connection to the sixteenth century. Yet it is also intriguing to see how those palaces flourished, declined or indeed were lost over the following century. Such is the case with the story of Whitehall Palace, for example, once Henry VIII’s seat of government and power in Westminster. This was, of course, consumed by fire and almost totally destroyed towards the end of the seventeenth century.

At the same time, Palaces of Revolution introduces us to new ‘houses of power’ that were constructed during the reign of the Stuarts. It includes many images of the elevations of buildings, floor plans and to-die-for colour reconstructions, drawn by the brilliant Stephen Conlin.

As ever, in Palaces of Revolution, Mr Thurley weaves in the story of the people and their palaces like no other. However, most poignantly, he leaves us in a reflective mood, summarising that by the death of the last Stuart monarch, Queen Anne, the royal court, and therefore its buildings, were no longer the theatre in which power was yielded. That now lay with parliament. Monarchs now ‘reigned not ruled’. Perhaps for a lover of medieval and Tudor history like me, this is a fitting way to conclude a chapter that extended from the Norman invasion; centuries littered with colourful characters, in whose wake was left a vibrant landscape of both triumph and tragedy.

I am very grateful to William Collins Publishers who have allowed me to publish this short extract from Palaces of the Revolution called, Into England. It is taken from the first chapter and details King James’ removal from Scotland and his arrival at the King’s Manor in York, the seat of the Council of the North, in the Spring of 1603.

Note: If you are interested, you will find a link to buy ‘Palaces of Revolution’ on both US and UK Amazon sites at the end of this extract.

Extract from ‘Palaces of Revolution’, by Simon Thurley: ‘Into England’

Just before midnight on 26 March 1603, Sir Thomas Carey brought James the news that he was now King of England. Two days later, the official papers in his hand, he was proclaimed king of Great Britain and Ireland at the Cross in Edinburgh. There were few preparations that needed to be made for his departure and on 5 April, James I rode out of the gates of Holyrood to make his way to his new kingdom. On 1 June he was followed by the queen and three of her children in a cavalcade of coaches. The doors of Holyrood were closed and the shutters fastened. Just over a week later, the Privy Council ordered an inventory of the contents of the house. There was a clock in the council chamber, some pieces of tapestry in the queen’s closet, an old carpet and a broken bed in the master of works’ rooms. By this time the furniture, the tapestries and all moveable valuables were in carts making their way south.

At first, James had no idea whether his arrival in England was going to be unopposed or whether he was to have to take the throne by force. His entry point was Berwick upon Tweed, the border town that had been sacked fourteen times before it finally became English in 1482. As the most vulnerable settlement in the country it had been heavily fortified, most recently by Elizabeth I who spent nearly £130,000 on an elaborate defensive system based on the latest Italian principles. From afar it was an impressive sight, although contemporary Scots opinion was dismissive of its strength.

An emissary sent by the king to ascertain whether he would be welcomed returned with the news that the keys of the city would be placed in James’s hand when he arrived. When his cavalcade approached, the great guns fired round after round in salute to their new sovereign and as the smoke cleared, James entered his kingdom and began to familiarise himself with a new world.

James’s youthful escapade to Denmark had been the only time he had left Scotland and his progress south was his introduction to the ways and the architecture of his new realm. Before James had left Edinburgh an itinerary had been agreed and his overnight stays scheduled.23 Robert Cecil, Queen Elizabeth’s secretary of state had wanted James to get to London quickly; indeed in the last months of Elizabeth’s life, James had himself written that ‘it shall be dangerous to leave the chair long empty, for the head being so distant from the body may yield cause of distemper to the whole government’. Yet the journey was not to be so quick.

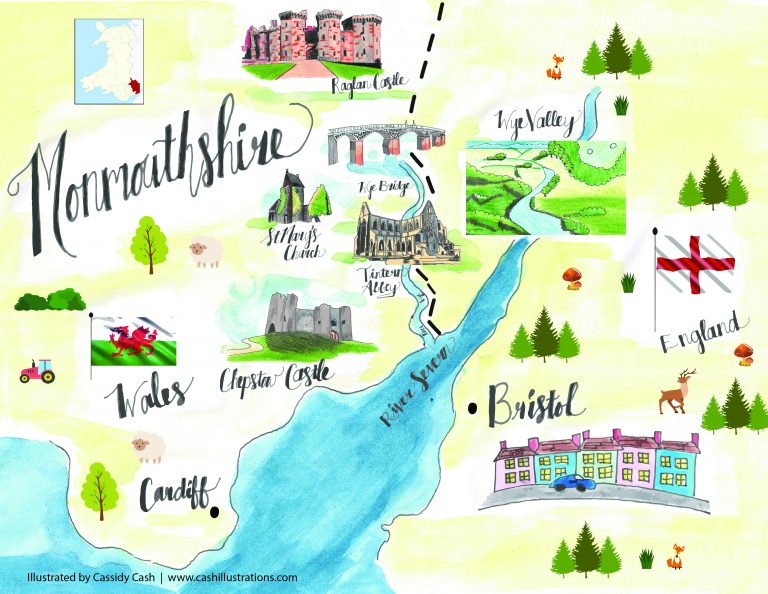

From Berwick, the king rode to Newcastle and then to Durham, where he stayed at the castle with the bishop. He must have been impressed by the gigantic cathedral and the lavishness of the Prince Bishop’s palace. He also visited several private houses, Widdrington, Lumley Castle, Topcliffe and Walworth Castle. But it was in York that James first set foot in one of his own residences.

York was a great city, ancient, wealthy and beautiful, dominated by the great minster church and surrounded by high walls and stout gatehouses. James considered it to be the second city of England and instructed that, on his entry, formal royal etiquette should prevail for the first time. Up from London rushed trumpeters, heralds, mace-bearers and a baggage train containing jewels, regalia, robes and all that was needed to keep the monarch in state.

MatzeTrier, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Council of the North, the administrative body that governed northern England, and York City Corporation had time to prepare for James’s arrival on 16 April. Once the civic reception outside the walls was over, the king walked to the Minster and, after being greeted by the clergy and hearing a sermon, was to be escorted to his house. James rejected the royal coach that had been sent to York for his convenience and asked to walk so that he might be seen by the townspeople and so, beneath a canopy borne by four knights, and preceded by a sword-bearer, mace-carrier and the city sheriffs with their white rods he arrived at the King’s Manor.

Henry VIII had fashioned himself a house out of the claustral buildings of St Mary’s Abbey just outside the city walls. It was one of the former abbeys that he had converted into a residence in the late 1530s, and it was pressed into use when Henry made his one and only visit to York in 1541. By 1603 this building was ruinous, and the royal residence was in the nearby former prior’s house which had been converted into a base for the Council of the North.

Here, nearly three weeks into his reign, James came face to face with English royal etiquette in one of his own houses. The King’s Manor had a great hall and three chambers of state: a great chamber, a dining (or presence) chamber and a privy chamber. Above, on the first floor, was his bedroom, closets and a gallery leading to the council chamber. There had been time to furnish the rooms richly, hanging them with tapestry, erecting a canopy of state and dais for the chair of state and installing a state bed. The king was met at the door by Thomas Cecil, Lord Burghley, president of the council, and was escorted by the sword- and mace-bearers to his chambers where the sword and mace were left while he was in residence. Burghley had stocked the extensive cellars and larders and, after feasting in the hall, James walked in the garden meeting local gentry. The next day he received the mayor, aldermen, sheriffs and others in his privy chamber where he received a gold cup.

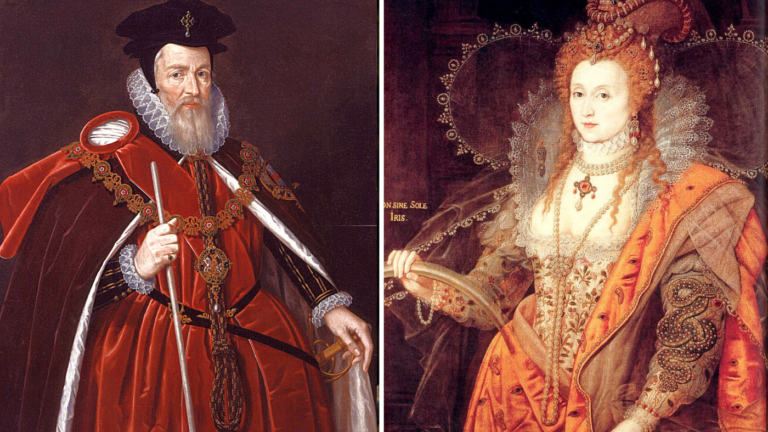

At the King’s Manor, in rooms that still exist, James received his first lesson in the ways of the English court and its protocols. His tutor was Sir Robert Cecil, half-brother of the Lord President, Thomas, Lord Burghley. Cecil was secretary of state, the leading royal minister. He knew that there were pressing military and political problems, but the agenda was led by the delicate protocol surrounding the burial of the late queen, the king’s southward progress, the makeup of his household, his entry into London and his coronation. Godfrey Goodman, Bishop of Gloucester, writing his memoirs some forty-five years later, recalled that the king first ‘took state at York and put his court into an English fashion, for there was no such state in Scotland’. He went on to explain that no monarchy ‘did observe such state and carried such a distance from the subjects as kings and queens of England’.

Goodman was unquestionably right: Elizabeth’s court had been stately and formal and both the queen’s femininity and maintenance of Tudor regal dignity kept her at arm’s length from her subjects. From the moment of James’s accession, he was surrounded by people hoping to secure titles, posts and offices, people hungry for pensions, grants and rewards, and those who simply came to catch a glimpse of their sovereign. Most people north of London had never seen their monarch and James’s progress through the northern counties was the opportunity of a lifetime.

You can buy Simon Thurley’s book, Palaces of the Revolution: Life, Death and Art at the Stuart Court, from Amazon UK or Amazon US. Please note: the link to buy ‘Palaces of Revolution’ on Amazon UK is an affiliate link.

If you wish to read my interview with Simon about his last book, Houses of Power, you can do so by following this link.