The Mirror of Great Britain: A Dazzling Symbol of Unity

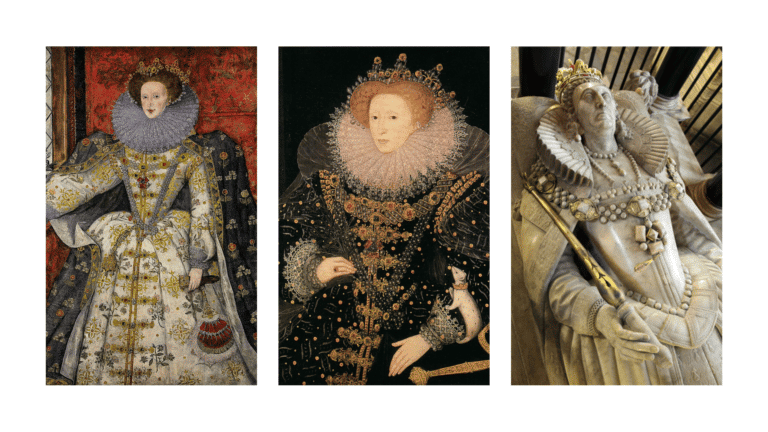

Some weeks ago, I penned a blog about a celebrated jewel of Renaissance Europe: The Three Brothers, once owned and much loved by Elizabeth I of England. So, much so that she is seen wearing it close to her breast on her tomb effigy in Westminster Abbey. During the writing of that blog, I was introduced to another spectacular jewel of the period. As before, this named jewel has an intriguing story that is even more convoluted than that of The Three Brothers, since the gems from which it was made were themselves of great repute. In this blog, I want to unpick the story of those celebrated gemstones, a diamond from the Great ‘H’ of Scotland and the Sancy diamond, as we explore the history of the magnificent Mirror of Great Britain.

The Mirror of Great Britain: A Glittering Symbol of Unification

This incredible tale begins toward the end of the story. The Mirror of Great Britain was a splendid jewel commissioned by James VI of Scotland and I of England as a glittering symbol of the new union of the two countries, which had come about through the death of the last Tudor monarch, Elizabeth I, in 1603. James inherited the English throne alongside his patrimony of Scotland, thanks to the Tudor blood flowing through his veins; his great grandmother was Margaret Tudor, daughter of the founder of the Tudor dynasty, Henry VII.

The Stuart dynasty was renowned for its love of fabulous jewellery, but the treasure trove of gemstones inherited from Elizabeth I were, of course, set for a woman. What is more, Tudor jewellery was fashioned in a style that was becoming increasingly outdated; while sixteenth-century jewellery made a great show of the setting of the gemstones, for the Stuarts, the gemstones themselves were the undisputed stars of the show.

Consequently, when James arrived in England, many of Elizabeth’s jewels were broken up and reset. One of the jewels to be created during this period was The Mirror of Great Britain.It is recorded in an inventory of 1606 as ‘a greate and riche jewell of gould called the MIRROR OF GREAT BRITTAINE, containing one very faire table diamonde, one very faire table rubie, two other diamonds cut lozengwise, the one of them called the stone of the letter H. of SCOTLANDE, garnished with small diamonds, two rounde pearles fixed, and one fayre diamond cut in fawcetts, bought of Sancy’.

As you can see from the image above the jewel is as described perfectly. James had a penchant for hat pins – and this is how he wore The Mirror of Great Britain. Alongside The Three Brothers, it was one of his most dazzling pieces, of which he seems to have been very fond. One of the gemstones, which we will talk more about in a moment, the Sancy diamond, is recorded as having been sold to James I in 1604 ‘pour s’en parer pour son entree’ – ‘to be worn at his entry’ (his ‘entry’ refers to the new king’s entry into the city ahead of James’ delayed coronation). So, we can see The Mirror of Great Britain being placed right at the heart of one of the most important days in the king’s life. However, to fully appreciate the jewel, we need to roll back the clock. For although The Mirror of Great Britain was a Stuart creation, at least two of the gemstones were much older and their origins surrounded in much myth and speculation. Let’s start with the first: The Great ‘H’ of Scotland, also known as the Great Harry.

The Great ‘H’ of Scotland (or The Great Harry)

Although there is no definitive visual depiction of the Great Harry, its presence as part of the Scottish Crown jewels, and as a personal possession of Mary, Queen of Scots, is well recorded and free from doubt. However, its origin is unclear. There are two theories as to how the jewel came to Scotland. The first is that it was a gift from Henry VIII to his sister, Margaret Tudor, who was the Scottish Queen at the time. This was later inherited by her granddaughter, Mary, when she ascended the Scottish throne in 1542, aged just six days old. However, given the grumbling animosity with the Scots and Henry’s gluttonous tendencies to covet beautiful and costly objects, I tend to believe the alternative explanation, that it was given to Mary during her time in France by her doting father-in-law, Henri II. Not only does this seem a more plausible scenario, but according to Scottish National Memorials: A Record of the Historical and Archaeological Collection in the Bishop’s Castle, it was set with Henri’s cipher.

The jewel was recorded in 1566, included in an inventory drawn up in anticipation of the forthcoming birth of Mary’s first child. Childbirth was, of course, a risky business and the inventory also reads like a will, bequeathing certain items of jewellery to various individuals in event of the queen’s death. The inventory is in old French and the first jewel listed among 180 entries of jewels alone is ‘une grosse bacgue a pandre facon de / H / en laquelle y a une groz diamant taille a faces et au dessus une pourmemoyre demoyet groz rubiz cabochin garny d’une petitte chesne‘, which basically translates to ‘a jewel fashioned in the shape of an ‘H’ with a large faceted diamond and hanging beneath it a large cabochon ruby’. Interestingly in the margin, there is an additional note stating that Mary wished that an Act of Parliament be passed that would annex the Great Harry to the Scottish Crown in memory of her and of the union with the House of Lorraine (a reference to her mother’s Guise relations); another piece of evidence that tips the balance in favour of the Great Harry being a treasure brought back from France and not a gift from the English King, Henry VIII.

Mary’s son naturally inherited The Great ‘H’ of Scotland from his mother. However, in reality, this was not a foregone conclusion, as one might have expected. Imprisoned on Loch Leven, Mary was obliged to entrust many of her jewels to her half brother, James Stewart, Earl of Moray. Once allies, the two were now the bitterest of enemies with Stewart becoming Regent after Mary’s forced abdication on 24 July 1567. According to the Scottish National Memorials referred to above he, ‘accepted the charge unwillingly; and certainly kept it most scandalously.’ Within several months, he had dispatched an envoy to London to sell many of Mary’s jewels to Elizabeth I. However, not the Great Harry, it seems. For after his assassination at Linlithgow, several Crown diamonds were found in the possession of his widowed countess. Imprisoned at Tutbury Castle in the Midlands at the time, Mary, Queen of Scots found out and was apparently furious, demanding that Lady Murray surrender the jewel. She initially refused and only after Elizabeth I’s intercession on numerous occasions did the Countess hand it back to the Scottish Crown. Thus, it was restored to the Crown and James I.

As we now know, the Great Harry’s diamond became part of the new English Crown jewels, shortly after James VI’s accession to the English throne. But what of the rest of the Great Harry? There is a record of the gold chain and ruby being ‘discharged’ to the earl of Dunbar in July 1606. What ultimately became of the remains of the Great ‘H’ of Scotland, and many other jewels once belonging to Mary, Queen of Scots is unknown, although the story of how many of them were gradually dispersed and lost over time is perhaps the subject of another blog – it is quite a tale! In the meantime, let us turn our attention to the other famed jewel of The Mirror of Great Britain: the Sancy diamond.

The Mirror of Great Britain and the Sancy Diamond

According to The Great Diamonds of the World. Their History and Romance, the origins and early history of the Sancy Diamond ‘seems to be wrapped in a dense cloud of mystery, defying the most subtle analysis, and impenetrable to the attacks of the keenest processes of reasoning’. Although there are certainly conflicting accounts of the jewel’s precise provenance, its path through antiquity and into the hands of the English Crown jewels can broadly be pinned down.

Let’s start with a few facts; the Sancy is an almond-shaped, pale yellow diamond weighing 55.23 carats. Just to put this into perspective, that is a tenth of the weight of the Cullinan I diamond, currently the largest cut diamond in the world and part of the English Crown jewels. The nature of its multi-faceted cut (on both sides of the jewel) was ‘unknown’ in Europe at the time it came to light and this is taken as evidence that the Sancy most likely originated in India. Confusingly, I have read two entirely different accounts of the early history of the jewel. The first is that it was acquired by Louis de Berquem for Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, who subsequently had it stolen (alongside The Three Brothers jewel) from his personal belongings after his defeat at the Battle of Grandson in 1476. However, an earlier account refutes this theory, saying that it was brought from the East by Monsieur de Sancy, during his time as French Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. This theory is also supported by this overview of the diamond in Jeweller Magazine.

So, who was ‘Monsieur de Sancy’? He was Nicolas Harlai, a courtier and French Ambassador to Turkey for King Henri III. He had a passion for collecting gemstones. After the accession of Henri III’s successor, Henri IV, Harlai became French Ambassador to the English court during the reign of Elizabeth I. Of course, he lived in London and was well placed to sell the jewel in England, which he did, after falling on hard times. However, before we come to the acquisition of the Sancy diamond by the English Crown in the latter part of the sixteenth century, we should pause to tell a quite remarkable tale of how the diamond was nearly lost from Monsieur de Sancy and recovered in quite the most unbelievable way possible. This tale may well be apocryphal, but it is often recounted in relation to the diamond’s history.

It is said that Monsieur de Sancy advanced the French King (Henri IV) the diamond so that it could be used as collateral to raise an army against the Swiss. At some point, the messenger carrying the diamond between the two men was apprehended and murdered. Having been told of this, Harlai was convinced that his loyal servant would have found a way to keep the diamond safe from his assailants. Thus, the place in which the unfortunate man was struck down and buried was located, his corpse exhumed and stomach cut open; yes, the man had swallowed the diamond to hide it. That’s loyalty, folks!

Whether this story is true, or simply part of the romantic myth that so often surrounds such gemstones, is unknown, but what is certain is that at some time during the later part of Elizabeth’s reign (after 1590) or after the accession of James I (depending on which account you read), the diamond was sold by Monsieur de Sancy to the English Crown. It is at this point that the gemstone seems to have acquired the name: ‘Sancy’, which it still bears to this day. Of course, James I of England had the diamond incorporated into The Mirror of Great Britain, as we have already heard. While many of the English Crown jewels were pawned overseas around the time of the English Civil War to fund the increasingly destitute Royal family, there are records of the Sancy diamond remaining in England as a possession of the English monarchy until 1695, when it was sold by James II to Cardinal Mazarin, for £25,000. He subsequently bequeathed it to Louis XIV of France upon his death. Thus, the Sancy diamond became part of the French Crown Jewels.

So, what became of the Sancy diamond? Predictably, it disappeared from the Royal Treasury at the beginning of the French revolution in 1792. Over the next couple of hundred years, it reappeared then disappeared several times over, passing through the hands of various private owners, the last of which was the Astor family. William Waldorf Astor, the owner of Hever Castle, purchased the diamond as a wedding gift for his new daughter-in-law in 1906 (only three years after purchasing the Boleyn family home). The Astors eventually sold it to the Lourve in Paris for $1million in 1978. You can see it there today in the Apollo Gallery. If you do make the journey to see it while on your travels, pause for a while and consider its eventful history; an Indian diamond, resting in a French museum, once was worn as a hat pin on an English / Scottish monarch to symbolise the union of two neighbouring countries, which had long been the bitterest of enemies. How strange is life!

Further Reading and Reference

Scottish National Memorials: A Record of the Historical and Archaeological Collection in the Bishop’s Castle, Glasgow, 1888

The Great Diamonds of the World. Their History and Romance by Streeter, Edwin William; Hatten, Joseph, 1841-1907, ed; Keane, A. H. (Augustus Henry), 1833-1912 joint ed.

Meubles de la Royne Descosse Douairiere de France: Catalogue of the Jewels, Dresses, Furniture, Books and Paintings of Mary, Queen of Scots, 1556-69. Edinburgh, 1863. p 97.

Three Royal Jewels: The Three Brothers, the Mirror of Great Britain and the Feather Author(s): Roy Strong Source: The Burlington Magazine, Jul., 1966, Vol. 108, No. 760 (Jul., 1966), pp. 350-353

Wikipedia: The Sancy Diamond

A truly amazing story!! Thank you for the wonderful blog covering this historic set of jewels!

Your article is very interesting. Written so that commoners can understand. Thanks!

????

Anyone who enjoyed these 2 articles on once English Crown jewels would enjoy reading Tobias Hill’s novel The Love of Stones, the story of the Three Brethren.