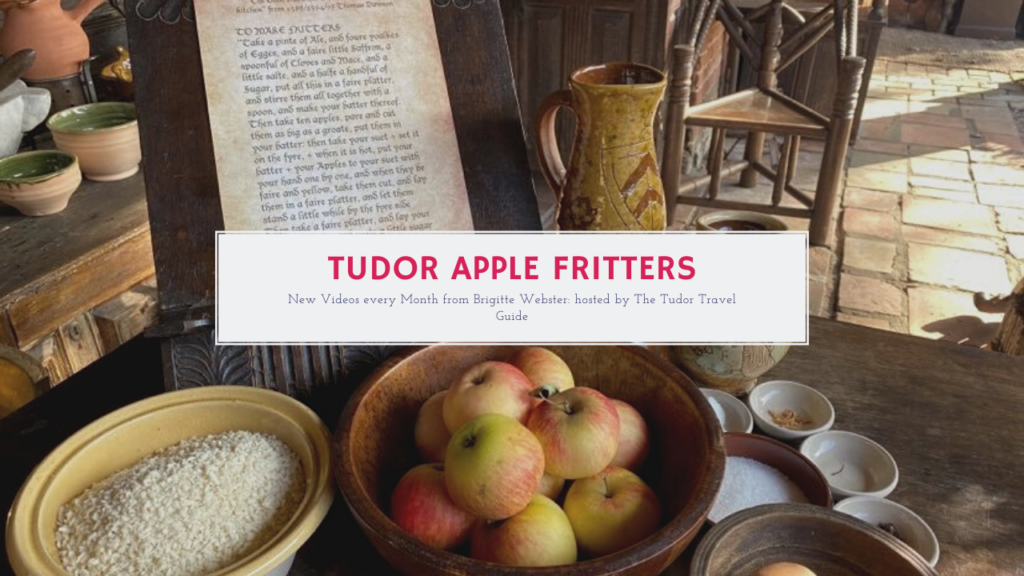

Tudor Apple Fritters: The Perfect Autumn Treat

Welcome to this month’s Great Tudor Bake Off! Once again, Brigitte Webster takes us on a culinary journey through Tudor England. last month our seasonal ingredient was the plum and we learned to make a fabulous Tudor Plum Tart. As it is September, this month, our seasonal ingredient will be the humble apple. Make sure you read to the end to watch Brigitte in her outdoor sixteenth-century kitchen making delicious Tudor apple fritters over a real fire – yummy!

The History of Apples in Tudor England

The Biblical claim that God planted apples “eastwards in Eden” was geographically correct because the genetic ancestor of the domestic apple grows wild in what today is known as Kazakhstan.

In England and northern Europe, apple cultivation may go back to Neolithic times. The Romans are thought to have introduced some varieties of apples to this country, while others were brought by the Normans, returning Crusaders and, in the fifteenth-century, by Huguenots. The first named apple on record was the Pearmain in 1204.

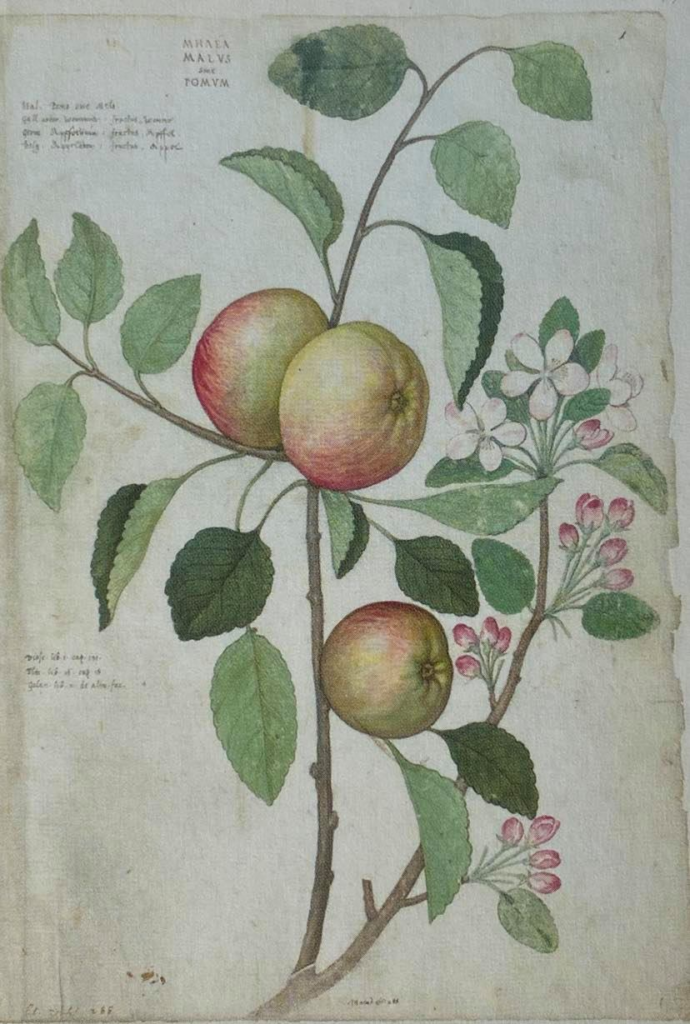

The name ‘apple’, from the Anglo-Saxon ‘appe’l is similar in Celtic. The original meaning of the word is unknown but it has been suggested that in Sanskrit, ‘ap’ means water and ‘p’hala’ means fruit. The Latin name ‘pomum’ is from the verb ‘poto’ meaning “I drink”.

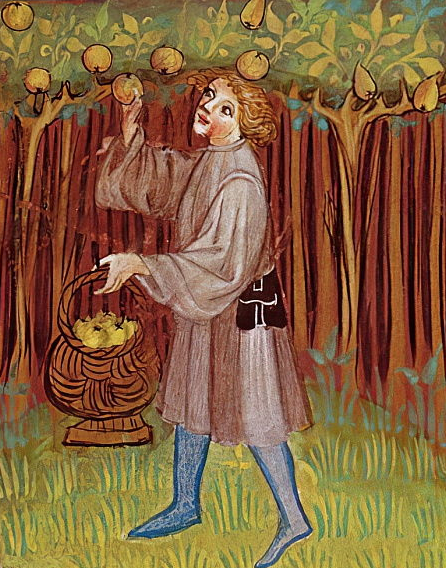

Apples were not just used as food. There are several cases of apples being used as payment in kind as, for example, from 1315 at the Runham estate in Norfolk where the annual rent was paid with 200 pearmain apples.

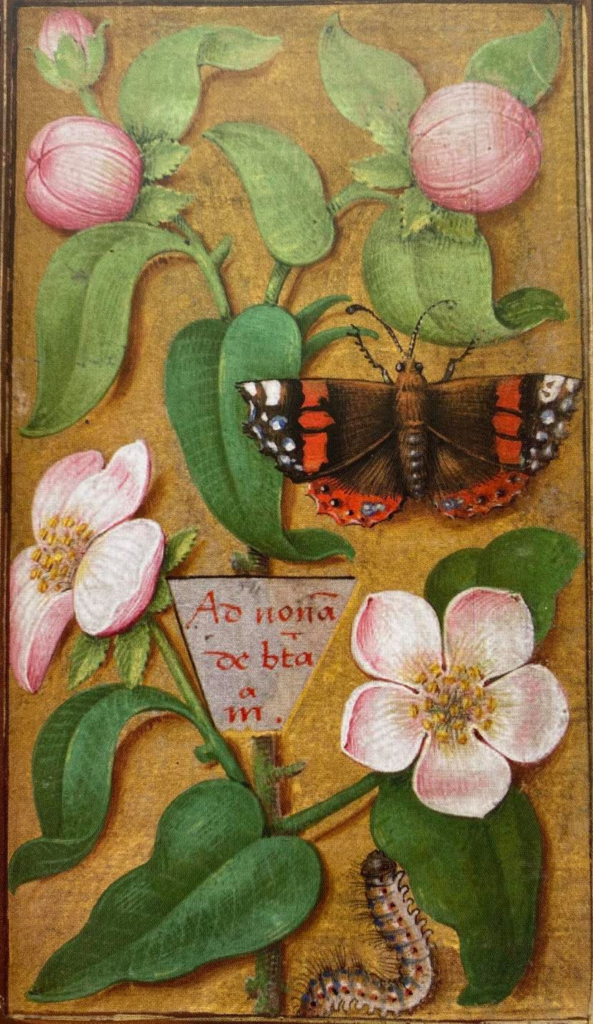

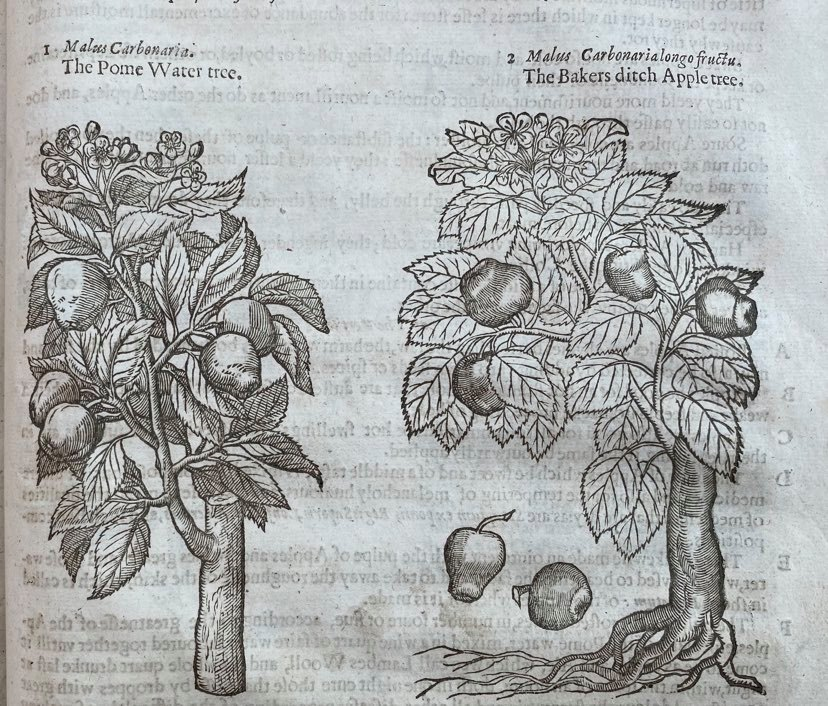

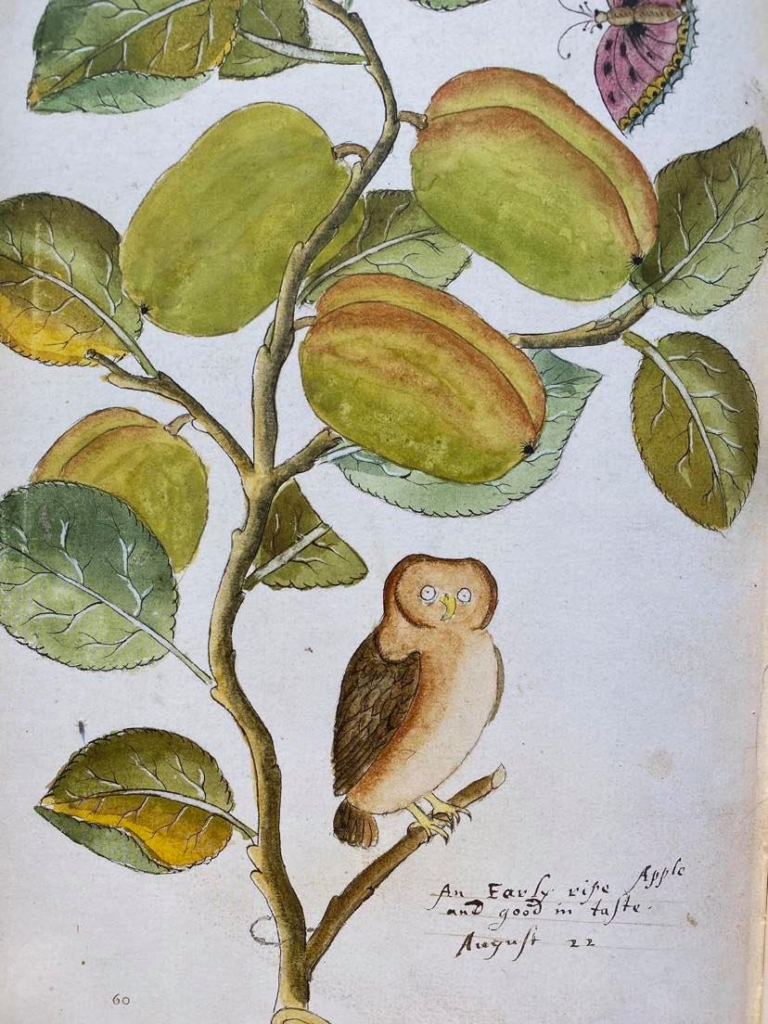

In his 1597 description of the apple, John Gerard names the fruit the “Pome Water tree’. He also informs us, that the skin can be red, green or yellow and the taste sweet as well as sour. He mentions, that ‘grafted’ apple trees are found gardens and orchards. It was the Greeks that learnt the oriental technique of grafting the steams of improved varieties of apples onto the rootstock of native trees, such as the quince in England. There is a record of Queen Eleanor of Castile, first wife of Edward I, who in 1280 bought grafts of the French “Blandurel” apple for her garden at the King’s Langley Estate in Hertfordshire.

Medieval records also give us an insight into the value of the apple. In a fruiter’s bill of 1292, ordinary apples were 3 pence and a hundred apples of the costard type set you back 1 shilling.

The monks of Reading Abbey were entitled by an agreement to an annual payment of one costard apple, possibly as some kind of ‘peppercorn’ payment. It is believed that it was a cooking apple.

The costard apple is said to resemble a head and hence the term costard head, which was used in Shakespeare’s play “Love’s Labour’s Lost’. Costard is an archaic term for apple or, metaphorically, a man’s head, therefore, in the play the character Costard is a comic country man.

The British word ‘costermonger’, a person selling fruit from a street cart, might come from the name of this apple. Some historians dispute this and suggest instead that cost-monger is the Saxon-English ‘ceaster-mangere’, a town trader.

William Lawson, a Tudor age botanist and garden adviser said in 1597, “ Of your apple trees you shall finde difference in growth. A good pipping will grow large, and a Costard tree: syead them on the north side of your other apples, thus being placed. The least will give sunne to the rest and the greatest will shroud their followes.”.

In Platins’s (1421-1481) On right Pleasure and Good Health, he advises that it is safer to eat sweet apples before a meal and sour ones afterwards. He also notes that sweet apples move the stomach and the bowels. The sweet variety which keeps over the winter would also take away inflammation and induce appetite. He also has an explanation for why the apple is ‘cold and damp’ – both properties considered dangerous for sick people – the juice of the apple turns to vinegar when pressed out. However, a healthy person has nothing to fear, as apples ‘moisten the belly and cool the inside’, something especially desired on a hot summer’s day!

William Turner, botanist and Dean of Wells cathedral, gives us the names of the apple in Greek, English, Dutch/German and French in his The Names of Herbes, published in 1548. Thomas Hill recommends in his The Gardener’s Labyrinth of 1577, that apples are best gathered near the ‘ful of the Moon’.

John Gerard in 1597, also goes on to tell us that in Hereford, there was a master whose servants drink nothing but apple juice. He also mentions the process of making ‘Lambes Wooll’, being the pulp of roasted apples mixed with wine and fair water. Apparently, this, drunk before going to bed, will help you empty your bladder. Gerard clearly prefers the ‘corrected’ boiled or roasted and spices added version of the raw, naturally cold and moist apple.

Shakespeare mentions various apple varieties such as Apple John, Bitter Sweeting, Codeling, Pippin, Pomewater and Costard but often uses the apple as a metaphor.

Here at the Old Hall, we grow over 50 fruit tree varieties, all known before 1700 and a good number of apple trees familiar in Tudor England such as:

- Costard

- Pearmain (oldest recorded apple in England dating to before 1200)

- Crab apple

- Codling

- Golden Harvey

- Pippin

- Winter Queening

- Decio (Italy)

- Edelsdorfer (Germany)

- Francatu (French)

- Couer De Boeuf (French)

- Rambour Franc (French)

Recipe: Tudor Apple Fritter Recipe

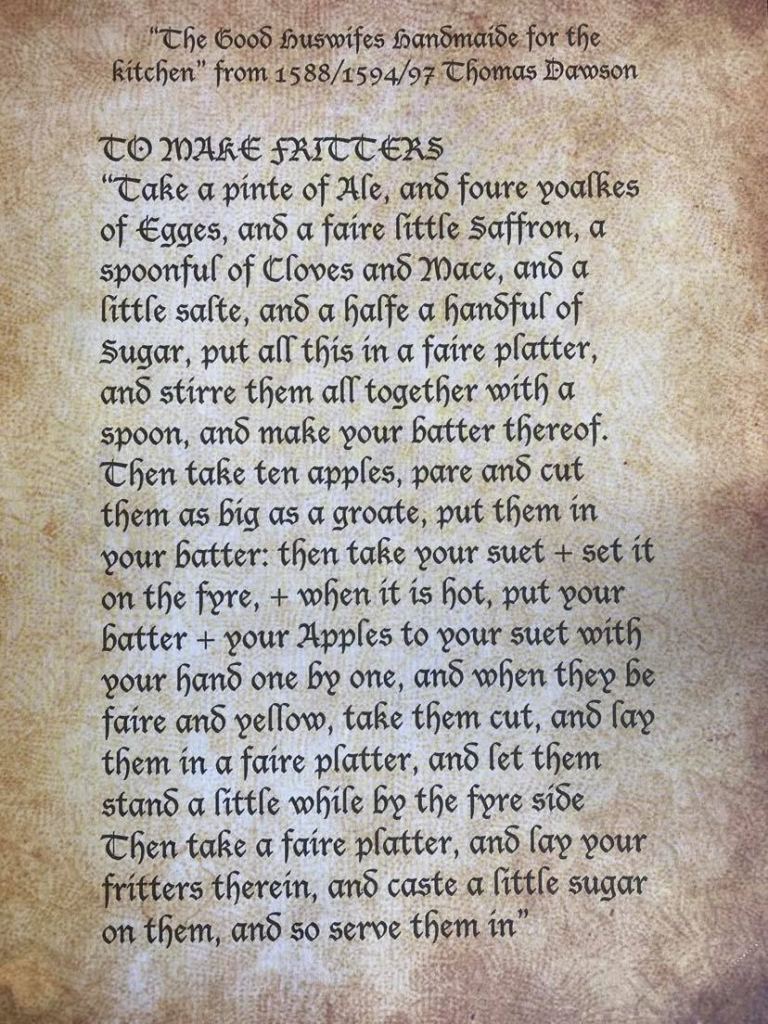

From ‘The Good Huswifes Handmaide for the kitchen‘ from 1588/1594/97 Thomas Dawson:

TO MAKE FRITTERS (Original Recipe):

‘To make Tudor apple fritters: ‘Take a pinte of Ale, and foure yoalkes of Egges, and a faire little Saffron, a spoonful of Cloves and Mace, and a little salte, and a halfe a handful of Sugar, put all this in a faire platter, and stirre them all together with a spoon, and make your batter thereof. Then take ten apples, pare and cut them as big as a groate, put them in your batter: then take your suet + set it on the fyre, + when it is hot, put your batter + your Apples to your suet with your hand one by one, and when they be faire and yellow, take them cut, and lay them in a faire platter, and let them stand a little while by the fyre side Then take a faire platter, and lay your fritters therein, and caste a little sugar on them, and so serve them in.’

TO MAKE FRITTERS (Modernised Recipe):

Ingredients:

- Half a pint of ale

- Two egg yolks

- 1 strand of saffron,

- ¼ teaspoon each of ground cloves and ground mace

- A pinch of salt

- Approx. 20-50g sugar (to taste)

- Enough flour or bread crumbs to produce a fairly thick batter (this ingredient is missing from the original)

- Note: if you use breadcrumbs to make these Tudor apple fritters, you need to let the mixture soak in the fridge overnight to achieve a smoother texture.

METHOD:

Mix all ingredients in a bowl with a whisk.

Wash, peel and cut 5 apples (I cored them and sliced them into rings).

In a frying pan, heat enough oil (or animal fat, such as lard or suet). Cover the apple pieces in batter and fry when the oil is hot. When they begin to get golden brown turn them and fry on the other side. When ready, remove and let most of the fat drip off by laying them flat on some kitchen paper towel.

Place the ready Tudor apple fritters, or rings, on a serving dish and sprinkle with icing (powder) sugar. I added some fresh corn flowers for decoration.

Serve and enjoy!

Brigitte’s Tudor Kitchen: A Demonstration

Click on the image below to watch Brigitte make Tudor apple fritters in her outdoor kitchen.

Sources and Further Reading:

A good huswifes handmaide for the kitchen, by Dawson (edited by Stuart Peachey)

On Right Pleasure and Good Health, by Platina (translated by Mary Ella Milham)

Food in Early Modern England, by Joan Thirsk

The Gardener’s Delight, by Thomas Hill, 1577 (edited by Richard Mabey)

Botanical Shakespeare, by Gerit Quealy

The Names of Herbes, by William Turner, 1548

Medieval Gardens, by John Harvey

Herball, by John Gerard, 1597/1633

Ashmole MS 1504, Bodleian Library

The Medieval Flower Book, by Celia Fisher

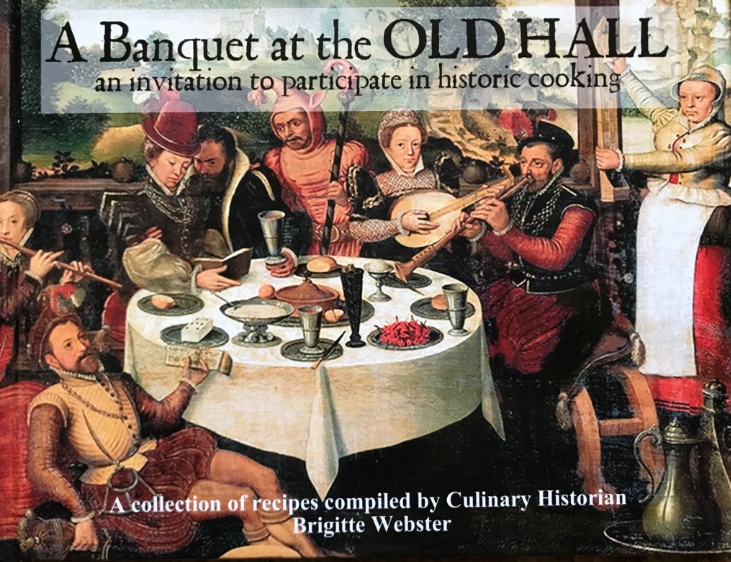

Each month, our Tudor recipe is contributed by Brigitte Webster. Brigitte runs the ‘Tudor and 17th Century Experience‘. She turned her passion for early English history into a business and opened a living history guesthouse, where people step back in time and totally immerse themselves in Tudor history by sleeping in Tudor beds, eating and drinking authentic, Tudor recipes. She also provides her guests with Tudor entertainment. She loves re-creating Tudor food and gardens and researching Tudor furniture.

Each month, our Tudor recipe is contributed by Brigitte Webster. Brigitte runs the ‘Tudor and 17th Century Experience‘. She turned her passion for early English history into a business and opened a living history guesthouse, where people step back in time and totally immerse themselves in Tudor history by sleeping in Tudor beds, eating and drinking authentic, Tudor recipes. She also provides her guests with Tudor entertainment. She loves re-creating Tudor food and gardens and researching Tudor furniture.