1502 Progress: Fairford, Gloucestershire

Itm the same day to a guyde that guyded the Quenes grace from Cotes place to Fayre ford.

The Queen’s Chamber Books

Fairford and the 1502 Progress: Key Facts

– After a couple of day’s lodging at Cotes Place, Henry and Elizabeth moved to their next destination: Fairford, in Gloucestershire, a once eminent Cotswold wool town.

– John Twyniho and his son-in-law, John Tame, wool merchants who were related by marriage, accelerated the prosperity and fame of the town on the back of the wool trade.

– The royal couple lodged as guests of the 31-year-old Edmund Tame for around four or five days, which was quite a considerable time for a royal visit.

–

Fairford: An Eminent Cotswold Wool Town…

After a couple of day’s lodging at Cotes Place, Henry and Elizabeth were on the move. An entry in the Queen’s Chamber Books records that a guide was employed to escort the couple to their next destination: Fairford, also in Gloucestershire.

Perhaps because of the recognised importance of the wealthy Tames of Fairford, we have our trusty antiquarian friend, John Leland, to assist us in reimagining the Tudor town. He passed through Fairford on his travels around the region. Luckily for us, the entry for the town is more verbose than usual. He begins by noting that from Lechlade (from whence he was travelling), the land around the town (of Fairford) comprised of ‘low ground, in a maner in a levelle, most apt for grasse, but very barein of woodde’. He goes on to say that ‘Fairford is a praty [pretty] uplandisch toune, and much of it [be]longith with the personage to Tewkesbyri [Tewkesbury] Abbay.

Like many English towns, Fairford’s historic tentacles reach back into prehistory with evidence of Iron Age settlement. Immediately after the Norman conquest, the town came into the ownership of the Crown. It was later transferred to the Earls of Gloucester, eventually appropriated by George, Duke of Clarence, through his marriage to Isabel Neville. Of course, when the Duke was convicted of treason, his property and lands were forfeited, and the manor of Fairford was returned to the Crown.

Image: Author’s Own

Enter John Twyniho and his son-in-law, John Tame; together, they would transform the town’s fortunes.

The Rise of a Provincial Wool Town

As Leland tells us in his Itinerary, ‘Fairford never florishid afore the cumming of the Tames onto it.’ Both Johns were wool merchants who were related by marriage. They were primarily responsible for accelerating the prosperity and fame of the town on the back of the wool trade and their connection to the Tudor Crown. In fact, of all the wool merchants of the Cotswolds, it was probably the Tames of Fairford who are the most well-known for their connection with Henry VII and his son, Henry VIII. Both monarchs visited the town during their respective reigns, with the latter’s curiously coming hot on the heels of Henry VIII’s return from The Field of Cloth of Gold in 1520.

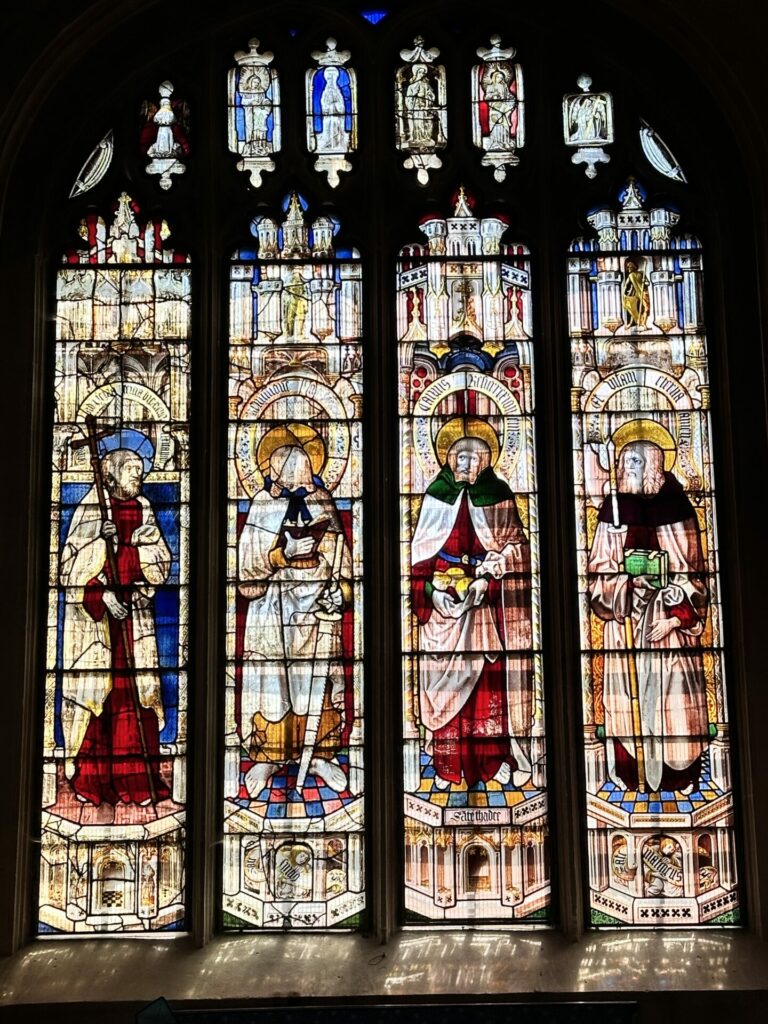

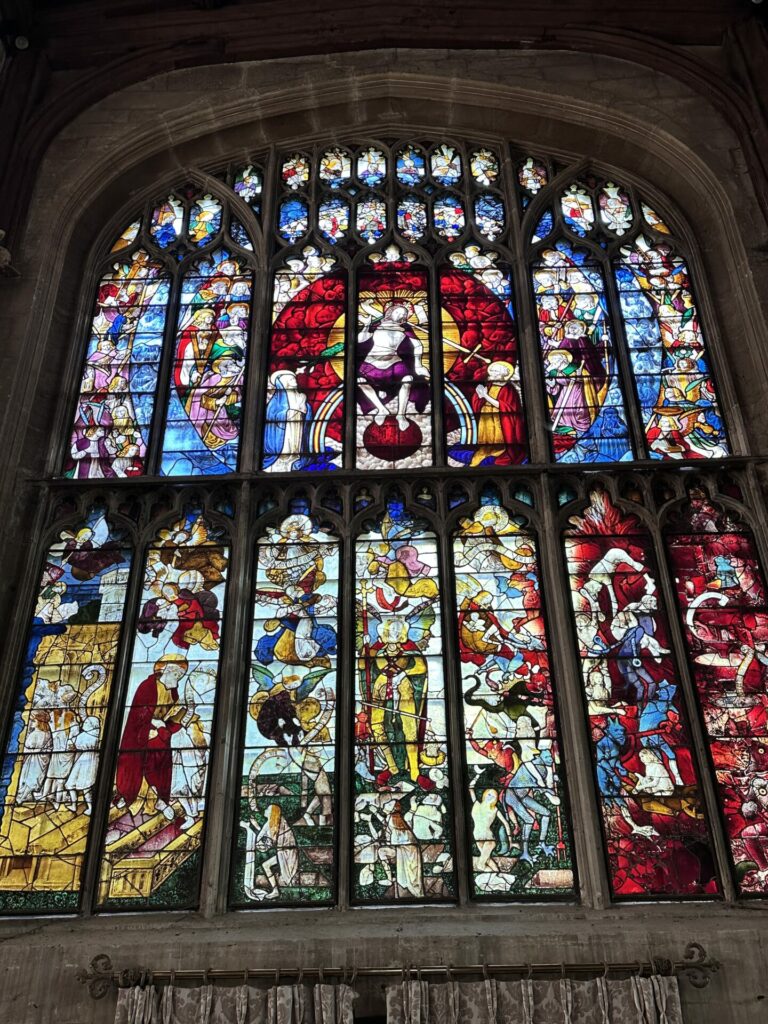

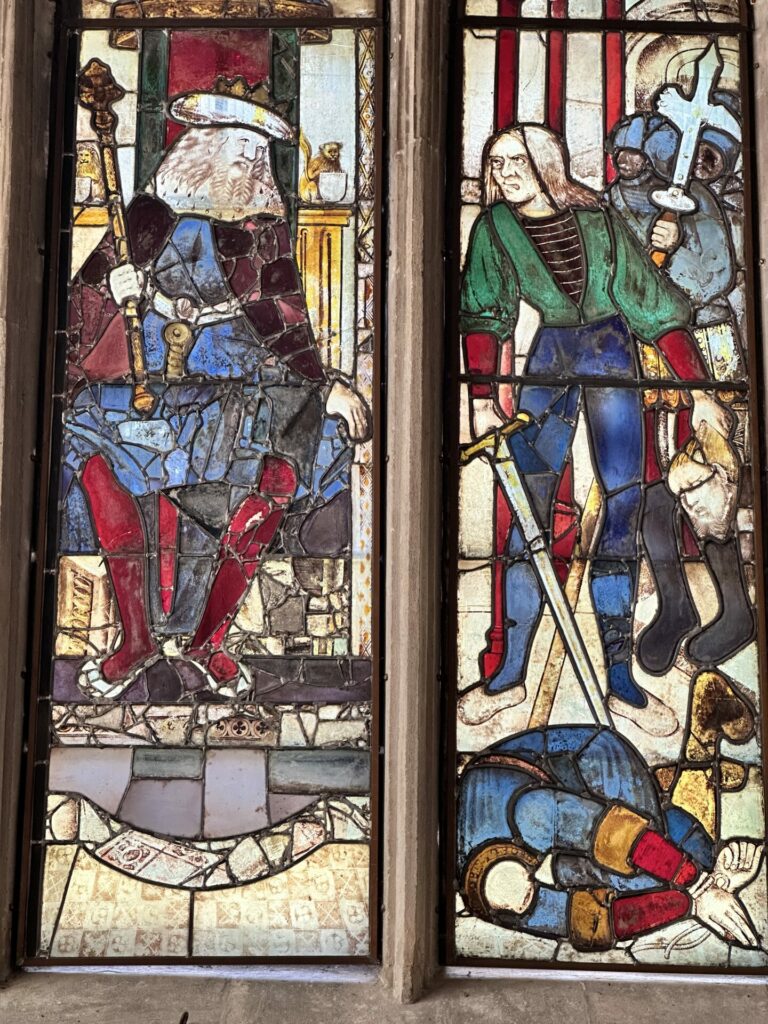

Their enduring connection to the Tudors is set in stone – or should I say ‘glass’ – at the heart of the current village. This is the Tudor treasure I mentioned in the previous blog: an unparalleled, complete set of Tudor stained glass in the parish church of St Mary. As Leland helpfully records, ‘John Tame began the fair new chirch of Fairforde, and Edmund Tame [John Tames’ son] finishid it.’ Thus, the rebuilding of the church commenced in the 1490s and was completed in 1497, with the windows added slightly later, between 1500-1517. By this time, John Tame had died (d. 1500), leaving his son, Edmund, to oversee the work and to host the royal visit. (Note: If you wish to hear more details about the church and its stained glass, you can tune into this episode of The Tudor History & Travel Show here.)

These dates make this royal visit to Fairford even more interesting. The church would have been newly refurbished, and the windows were in the process of being installed. The stained glass is of the highest quality and has now been attributed to Henry VII’s royal glazier, Bernard Flower. Galyon Hone, glazier to Henry VIII, may also have been involved.

The Tames Rebuild Fairford Manor

The Tames did not have to travel far to see their programme of work unfolding at the church. Although we have precious few details of the Tame’s once grand manor house (which is now wholly lost), Leland records something of its location and grandeur when he writes: ‘There is a fair mansion place of the Tames hard by the Glo’sterchirch yarde, buildid thoroughly by John Tame and Edmunde Tame. The bakside wherof goith to the very bridg of Fairford.’

Once again, we learn that John Tame was responsible for constructing the Tame family home and that the manor was positioned directly adjacent to the church but extended to the rear as far as the River Coln and the bridge that crossed it. The Victoria County History adds a little more detail, stating, ‘Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick (d. 1471), is said to have had a manor-house called Warwick [or Beauchamp] Court north of the church. John Tame and his son Edmund rebuilt the house, which apparently had ranges west and south-west of the church.’

Thus, John Tame seems to have aggrandised an existing medieval manor house, which could have comprised at least three ranges, wrapping itself around the rear of the church to the north, west, and south-west. If you visit today, you will understand just how much land this covers and what an impressive manor house must have greeted Elizabeth and Henry when they rode into Fairford around 10 September 1502.

Image: Author’s Own

The couple lodged as guests of the 31-year-old Edmund Tame for around four or five days, which was quite a considerable time for a royal visit (not to mention the significant financial burden this must have been to the family). However, Edmund was a wealthy commoner with deep pockets, and the Tames were gracious hosts. No doubt they were more than happy to host the King and Queen, given that their closeness to the Crown would have brought them prestige – and not forgetting that there were some profitable deals to be done.

For instance, we know that just two years before the visit, in 1500:

‘the kinges grace & sir reginold bray haue made a bargayn with edmond tame of fairford in gloucester shir for cl sakkes of wulles whereof twoo of fyne and one of mydell wulles to be deliuered at london pakked & dressed redy to be shipped to calais & to be taken after the weght of the bealme of london for the price of x marces & anoble for euery sakk.’

Modernised: ‘The King’s grace & Sir Reginald Bray have made a bargain with Edmond Tame of Fairford in Gloucestershire for 150 sacks of wools whereof two of fine and one of middle wools to be delivered at London packed & dressed ready to be shipped to Calais & to be taken after the weight of the beam of London for the price of 10 marks & a noble for every sack thereto be delivered at his costs & charge before April next.’

Image: Author’s Own

This equates to an enormous sum of money and indicates just how lucrative the wool trade could be for entrepreneurs who ‘made it’.

A Royal Stay at Fairford

The Queen’s Chamber Books include several items relating to Elizabeth’s time at Fairford. Once again, Lord Saintmonde (St Amande) is diligent in keeping the queen supplied with ‘bukkes’ from his apparently well-stocked hunting parks of Blakemore and Pevisham in Wiltshire – nine in total! 11 more arrived from the keepers of the parks at Cosham and ‘Devyes’ (Devises). However, these do not seem to be gifts. It is clear from a later entry in the Queen’s Chamber Books for November 1502 that these bucks arrived at the Queen’s behest.

‘“Nov”. Paid to John Duffin for riding from Berkley-herons to Pevesham and Blakemore to the lord Saintmond [St Amand. Lord Beauchamp of Bromham?]. From thence to the park of Corsham; from Corsham to the Devizes; from thence to the forest of Savernak to Sir John Seymour for bucks for the King’s grace.’

So rather than gifts for the Queen, we see Elizabeth ordering venison for the King’s table. Is this a gift paid for by Elizabeth for her husband, or is she being thoughtful and providing extra food to alleviate the strain placed upon their hosts?

Other items record a payment to John Staunton, a member of the queen’s household, for money given to the servant of Lady Hungerford for bringing a gift of apples to the Queen, while another payment was made to the Queen’s laundress, Agnes Dean. Thomas Acwurth [Acworth] had his expenses reimbursed relating to the Queen’s stable, and finally, payment was made for the ‘making of twoo dublettes forthe Quenes fotemen of crymsyn velvet’.

Henry VIII Visits Fairford: 1520

While it is not recorded in the Chamber Books, it is hard to believe that Edmund did not show off the newly refurbished church with its richly painted stained glass windows. Perhaps the royal couple also paid their respects at the tomb of Edmund’s recently deceased father, John, whom Henry surely knew well.

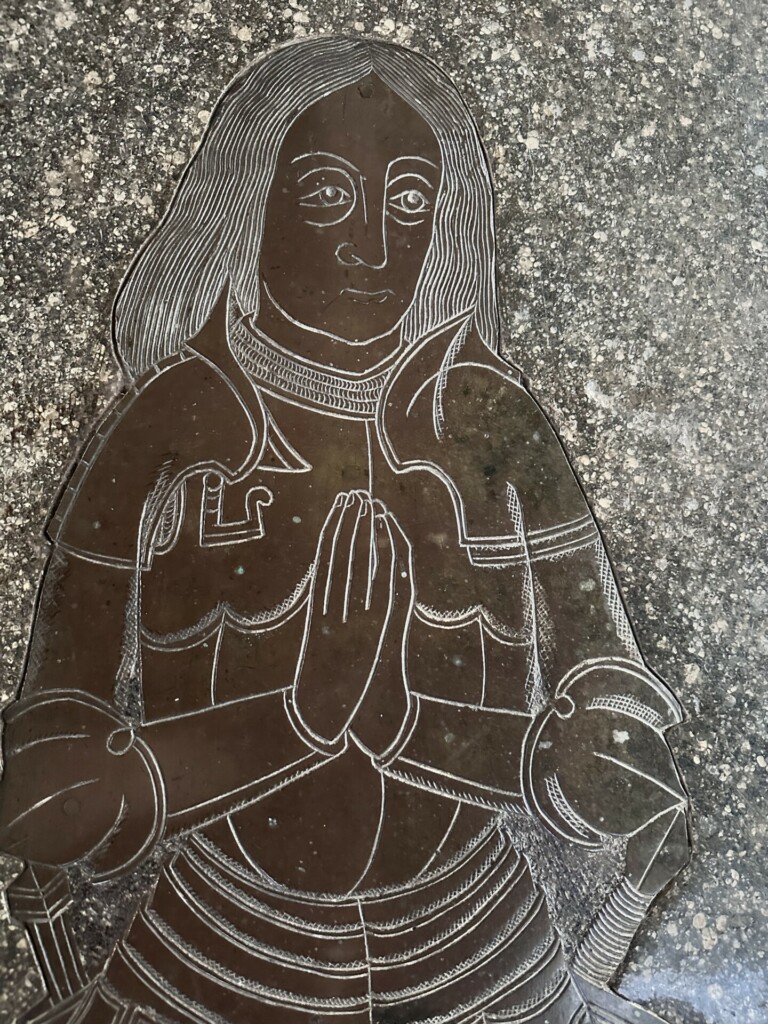

Image: Author’s Own

His marble chest tomb can still be seen near the high altar in the chancel. The wording on the tomb is in Latin and reads:

Orate pro animabus Joannis Tame armigeri. Alicia uxoris ejus. qui quidem Joannes obiit 8. die mensis Maij, A. D. 1500, an0, regni Regis Henrici 7. Et prcedicta Alicia obiit 20. die mensis Decembris Ann0. D. 1471.

Translated, this means:

Pray for the souls of John Tame the squire, and his wife, Alice. John died on the 8th day of May, A.D. 1500, an0, of the reign of King Henrici 7. And the aformentioned Alice died on the 20th day of the month of December Ann0. D. 1471.

Edmund would go on to garner more glory. He was appointed Sheriff of Gloucester and a Member of the Commission for Peace and was knighted by Henry VIII in 1516. During the latter’s visit to Fairford in 1520, when the King stayed at Tame’s manor house for six days (26 August and 2 September), Edmund was created ‘steward for the life of the lordship of Fairford’. His young son, also called ‘Edmund’ was knighted at this time.

Sir Edmund Tame died on 1 October 1534. He has a memorial plaque in St Mary’s Church. It reads:

Hie jacet Edmundus Tame miles Agnes, Elizabeth uxores ejus. qui quidem Edmundis obiit primo die Octobr. anno. D. 1534. anno regis Henr. 8. 26.

Which translated reads:

Here lies Edmund Tame, the knight, Agnes, and Elizabeth his wife. who indeed died on the first day of October. in the year D. 1534. in the year of King Henry 8. 26

There has been a lot of speculation about why Henry VIII came to Fairford in 1520, travelling directly to and from the market town and so soon after the grandiose three-week extravaganza celebrated as The Field of Cloth of Gold.

Sam Harper, one of the team responsible for transcribing the Queen’s Chamber Books, has shared an interesting thought: as the new Prince of Wales, was Henry Tudor travelling with his parents during the 1502 progress after all? The windows of St Mary’s contain the Prince of Wales’ feathers; were these included early on in the design to honour the 11-year-old prince? Alternatively, was it simply Edmund who extended a special invitation to view the completed windows? Another thought might be that Henry VIII visited Fairford as he needed an injection of cash from the filthy-rich Tame family following the lavish expenditure he had incurred at The Field of Cloth of Gold. We can but speculate!

Elizabeth of York’s Final Progress

Around 14/15 September, Elizabeth and Henry left Fairford behind. Like many locations on this progress, they would never see it again. For Elizabeth, she was now four months into her final pregnancy. Throughout the progress, we have witnessed her making offerings at religious institutions as intercession for her safe delivery. Sadly, this was not to be.

The royal couple made their way across the county border, back into Oxfordshire, arriving at the King’s Manor of Langley around 16 September. They had been travelling for around eight weeks. Before leaving Oxfordshire behind, they revisited the nearby Palace of Woodstock, then headed south, back to London. It would be the 35-year-old Queen’s final progress. Five months later, on 2 February 1502, she would deliver a daughter named Katherine. Within days, both were dead.

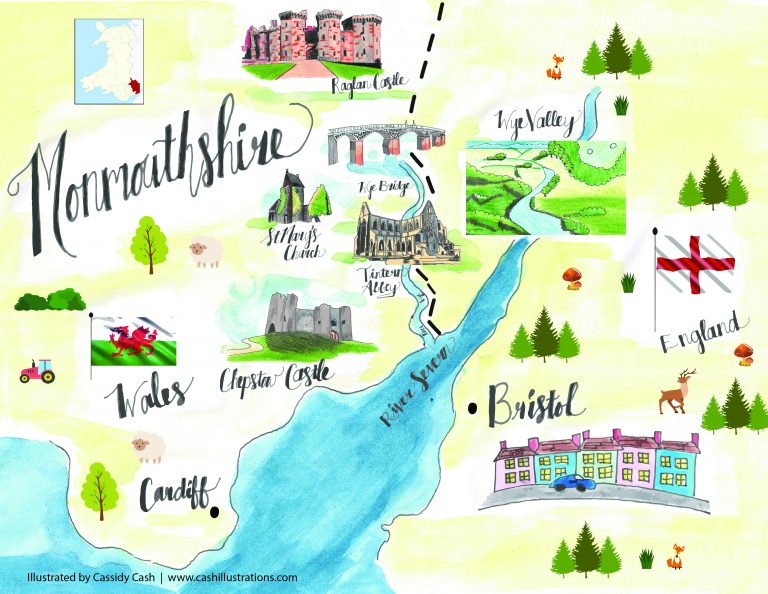

This progress had been much more of a trip down memory lane for Henry than the more usual state progress, returning to his erstwhile childhood home at Raglan Castle, the centrepiece of the progress. Along the way, the King had travelled with his Queen through glorious, sleepy English countryside during the height of summer. The couple had met with old friends, rekindled acquaintances and possibly done some lucrative ‘buisness’ with the wool merchants of the Cotswolds along the way.

Henry must have hoped that he had seen the last egregious death. Although battle-hardened and having witnessed much loss and suffering in his time, the recent years had been different. He had lost people in peace, not war. These most recent deaths were of those of close friends and family, who had loved and supported him through enormously trying times. The grief cut deep, but surely, he could not have imagined that his next loss would cut the deepest of them all.

The marriage of Edward IV’s eldest daughter and the founder of the Tudor dynasty had united a kingdom soaked with the blood of two feuding families. Henry and Elizabeth had grown up as enemies across an apparently irreconcilable divide, but somehow, in marriage, they came together and, it seems, loved each other deeply. Henry would continue to travel around his kingdom, gradually becoming ever more London-centric as his health gradually failed him. Still, he would travel on alone, without his beloved wife at his side. Perhaps as his life and reign drew to a close, he treasured those memories of a final, lingering summer together when the pair had hoped beyond hope for a happy ending.

To listen to a podcast about Fairford, the Tames and the Tudor stained glass windows with this blog, click here.

FAIRFORD MARKS THE FINAL STOP ON THIS 1502 PROGRESS. I HOPE YOU HAVE ENJOYED THE JOURNEY.

Places to Visit Nearby

Church of St John the Baptist, Cirencester (14 miles): The Cotswolds is home to some incredible historic churches. An area made rich by its wool trade in medieval times, wool merchants often funded the construction and renovation of churches, which became known as “wool churches.” In this podcast episode, I tour St. John the Baptist in Cirencester and St Mary’s Church in Fairford, two of the most prominent of these wool churches.

Sources

Henry VIII’s visit to Fairford, 1520, and the Tudor Chamber Books. Online Article by the Fairford History Society.

The itinerary of John Leland in or about the years 1535-1543. Edited by Lucy Toulmin Smith by Leland, John, 1506?-1552; Smith, Lucy Toulmin, 1838-1911.

‘Fairford’, A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 7, (Oxford, 1981), pp. 69-86. British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol7/pp69-86 [accessed 15 June 2024].

A History, Military and Municipal, of the Ancient Borough of the Devizes. LONDON: Longman, Bkown, & Co., Haiernosteu Row. DEVIZES: IIenky Bull, Saint John Stiieet. 1859.

The Tames for Fairford, by Chris Hobson. 2013.

CONCILIAR POLITICS AND ADMINISTRATION IN THE REIGN OF HENRY VII by Lisa L. Ford. A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews. 2001.

Cirencestre: The Medieval Period, by Cotswold Archaeology Trust. Cirencester.