Tudor Stepney & Thomas Cromwell’s ‘Great Place’

Cover Image: Worcester House with Tudor Stepney in the background. Image courtesy of MOLA

Anyone who knows me will be aware that Anne Boleyn is my historical heroine, but lately, I admit to having developed a growing fascination with her nemesis: Thomas Cromwell, his protégés, such as Sir Richard Rich and Sir Ralph Sadler, and his properties, including those in Austin Friars and Tudor Stepney.

The Rise and Rise of Thomas Cromwell

Whatever Thomas’ role in the downfall of the Boleyns, it is certainly hard to ignore his exceptional talents. This list is long: a mastery of at least three European languages, business, law, and politics; a cosmopolitan outlook on life that stretched far beyond English shores; a wily ability to manage his master, King Henry VIII, one of the most fickle and dangerous monarchs of the Western world; and his reputation with contemporaries as the most affable of hosts.

So we might say that Cromwell was truly a self-made man of his time: ruthless but immensely cultured. This was the perfect combination of attributes for an aspiring Renaissance courtier, whose role as the principal legal mind of the age required, at times, amiable sophistication sheathed with a core of cold-hearted steeliness.

We can very briefly summarise Cromwell’s career as follows: having cultivated many of his linguistic and business talents abroad, grown an expanding network of associates and polished the edges off his youthful thuggishness in Italy and the Low Countries, Cromwell returned to England around 1512/3, aged around 27; he married in 1515, trained as a lawyer, and after first entering Thomas Wolsey’s service circa 1519, rose rapidly through the ranks of Henry’s court. He was elevated to serving as the King’s Principal Secretary by 1534, created Lord Privy Seal and Baron Cromwell of Wimbledon by 1536 and finally, shortly before his execution, ennobled as the Earl of Essex in 1540.

During his incredibly successful mercantile and then legal career at court, Cromwell transacted his business in the heart of London. At the end of a hard’s days work, he could lodge in one of his two London properties: ‘The Rolls’ on Chancery Lane (his official residence as Master of the Rolls) or retire to his grand townhouse of Austin Friars, also in the City of London. If he sought peace away from the noise and stench of the metropolis of Henry VIII’s capital, Cromwell could venture beyond the city walls to one of his two country houses situated close to London in nearby Tudor Stepney or Hackney.

Having previously explored the fascinating story of Thomas Cromwell’s Austin Friars home in this blog, I turn my attention to Tudor Stepney. It is a personal quest to find out more about Cromwell’s house there—and for very good reason. I have long been fascinated by the place where it is said that Cromwell tortured an unsuspecting Mark Smeaton on 30 April 1536. Those ‘conversations’ would directly result in the arrest of Anne Boleyn and the seven men initially arrested alongside her.

The opportunity to learn more about this location is just too delicious to ignore for one moment longer. So, follow me as we retrace Cromwell’s steps and uncover what we know about Tudor Stepney and the place where these menacing and historic events unfolded.

Tudor Stepney

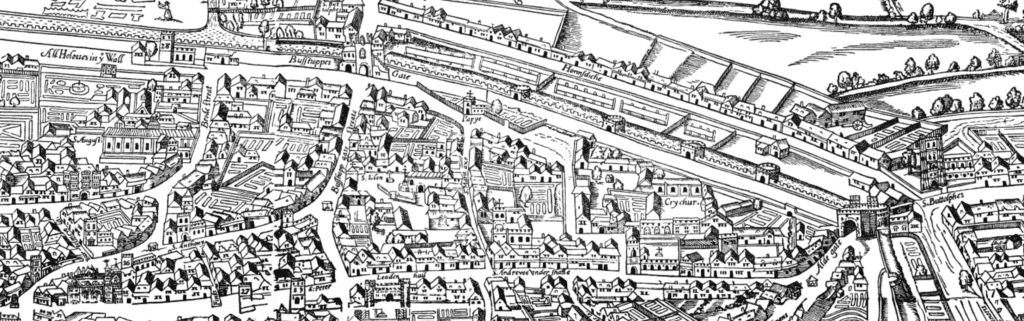

Thomas Cromwell’s swanky Austin Friars’ townhouse was located in the northeast corner of the City of London, adjacent to the priory of Austin Friars and within a short walk of Bishopgate (see the image above). This heralded the beginning of the ancient Roman road of Ermine Street, which connected London with the venerable northern cities of Lincoln and York. However, just beyond the gate, a road running eastwards and parallel with the city wall along its north edge soon joined Aldgate Street next to Aldgate. Outside the city walls, Aldgate Street headed northeast away from the City towards the Parish of Stepney. Perhaps this was Cromwell’s route to ‘commute’ between his Austin Friars and Stepney properties?

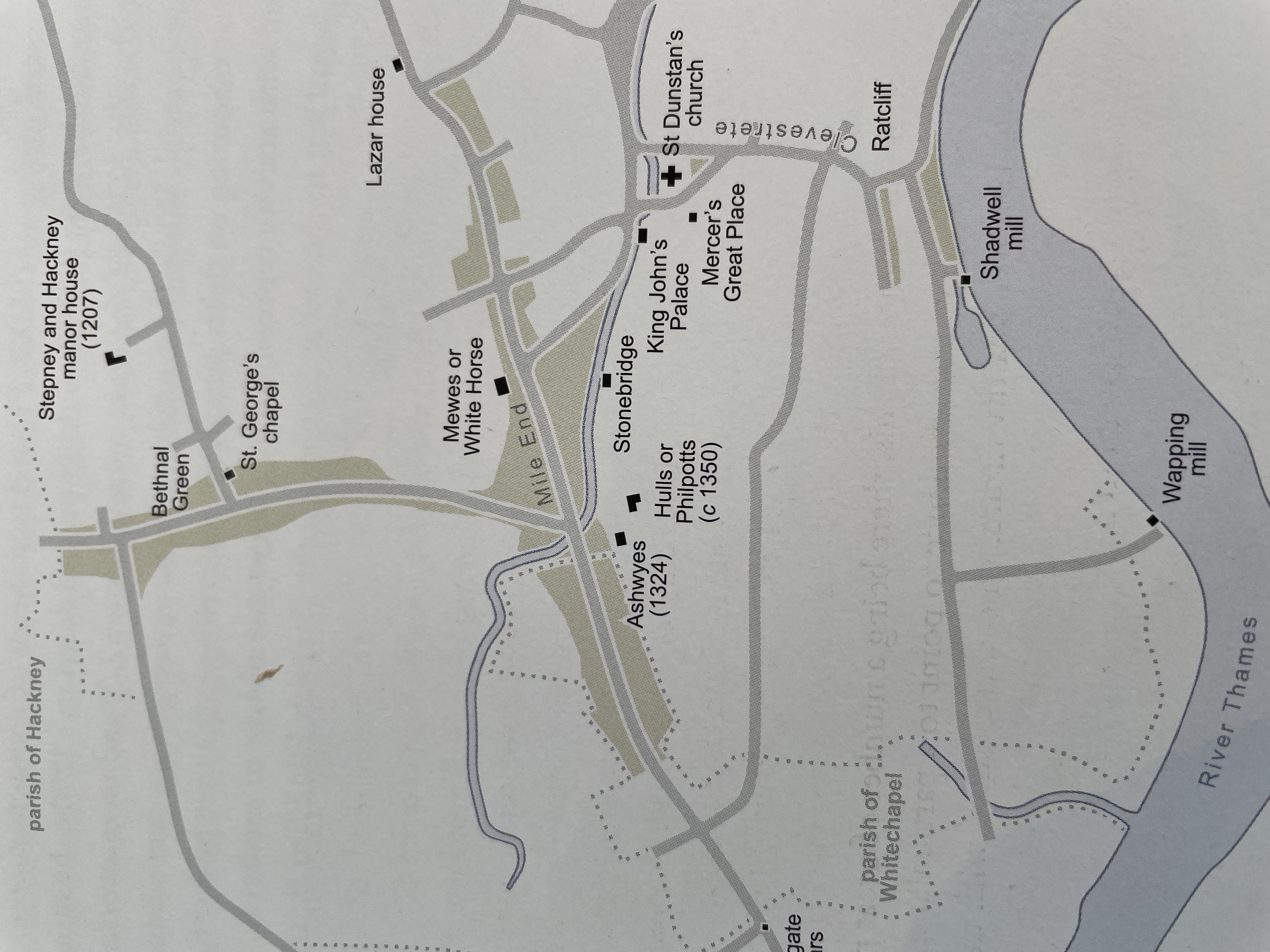

While Chelsea was renowned as a place for the well-to-do of Tudor London that lay west of the capital, Stepney filled a similar niche on the east. At the centre of the parish was St Dunstan’s Church, which still stands today; it is about a 40-minute walk from the City and an easy ride from central London for our man of the moment. In fact, we know that Cromwell’s house in Tudor Stepney was situated just to the south-west of St Dunstan’s Church, so we can be pretty sure of how long it took Thomas to commute between these two London-centric houses!

According to David Sankey in Stepney Green: Moated Manor House to City Farm, by the thirteenth century, ‘Stepney had established itself as an important village, a quiet dormitory settlement that provided secluded desirable residences for the rich and powerful.’ As noted, Cromwell was originally a cloth merchant before his meteoric rise at the Henrician Court. He retained an ongoing network with overseas merchants, and perhaps it was also convenient that Stepney was not too far from the docks at Wapping and Limehouse, which was situated on the north bank of the Thames.

Sankey describes how the road from London to Stepney was ‘dotted’ with large houses, including Ashwyes (built 1324). Hulls / Philpotts (built circa 1350), Westmeath (built 1406) and Worcester House (see image below). Each house had large ‘walled and hedged private parcels of land attached to the mansion’. This arrangement attracted wealthy Londoners who needed access to the city to conduct business but whose daily commute could quickly bring them into Stepney’s clean, country air.

Cromwell’s ‘Great Place’ in Tudor Stepney

As I have already mentioned, at the centre of the parish of Tudor Stepney was the ancient church of St Dunstan, named after the tenth-century Bishop of London. An early Saxon church was rebuilt after the tenth century and rebuilt again in the fifteenth century, with later Victorian ‘renovations’ of its exterior. Amazingly, St Dunstan’s made it through the Blitz intact. So, the church we see today is essentially the one Cromwell would have seen every time he visited his Stepney home. It really is a true survivor of time!

The house that Cromwell rented was owned by the Mercers’ Company, with whom he had close ties (of course, as I have said, he was an ex-merchant himself). Before it became part of the Mercers’ property portfolio, at the turn of the sixteenth century, Sir Henry Colet acquired the land upon which the house was built. He was twice Lord Mayor of London and knighted by Henry VII as part of the celebrations associated with his marriage to Elizabeth of York.

Henry Colet died at his manor of Stepney in 1505 and was buried in St Dunstan’s, where his son, John Colet, had once been the vicar. Interestingly, John Colet was an early humanist and reformer of the church. He did much to influence Erasmus when the latter visited him at Oxford in 1498. It seems the English reformation was already in the air at Tudor Stepney long before Cromwell brought with him his grand plans for monastic reform!

Anyway, back to our story! John Colet became the Dean of St Paul’s the year of his father’s death. According to the Victoria County History, ‘In 1518 they (John and his mother, Dame Christine) vested them [the land and manor] in the Mercers’ Company for the maintenance of St Paul’s School, which John had founded in 1512′. Afterwards, Christine continued to live at the manor house, which the Mercers’ called their ‘great mansion place’ and would later be known as the ‘Great Place’, until her death in 1523. The Mercers then rented the mansion to another twice Lord Mayor of London, Sir John Aleyn. He seems to have left by 1533 – a momentous year if ever there was one! Enter Thomas Cromwell…

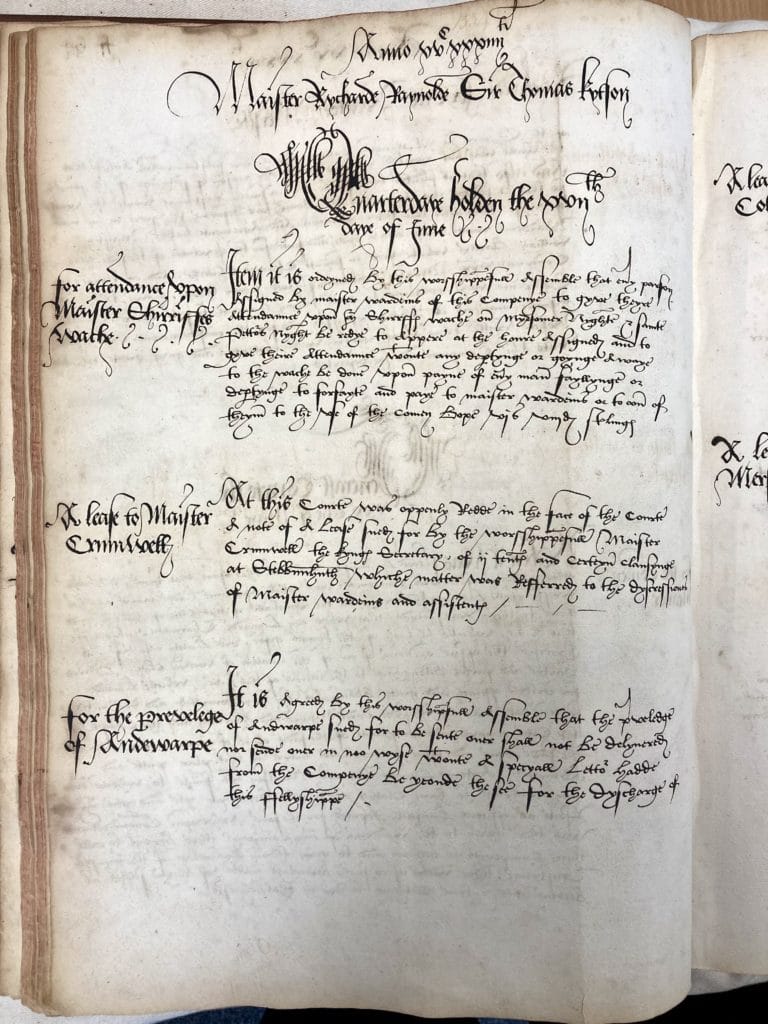

Cromwell took a 50-year lease of the mansion and set about renovating it. According to the Mercers’ Company, they do not have an original or copies of the actual lease. Still, they do have documents mentioning the Company’s administration of Cromwell’s lease in the Acts of Court (see above). A transcription of these is included in full in the Appendix below.

According to these documents, Cromwell took possession of ‘two closses nowe made in oon conteynynge xij acres, late in the tenour of Sir John Aleyn, knyght, a closse of vi acres there late tenour of Robert Studley, mercer, a tenemente and a gardeyn there late in the tenour of William Gresham, mercer, with thappourtenaunces, for the terme of fyftye yeres.’ In summary, along with the ‘mansion place’ a total of 18 acres, gardens and ‘appurtenaces’, amalgamating land and buildings from three previous tenants.

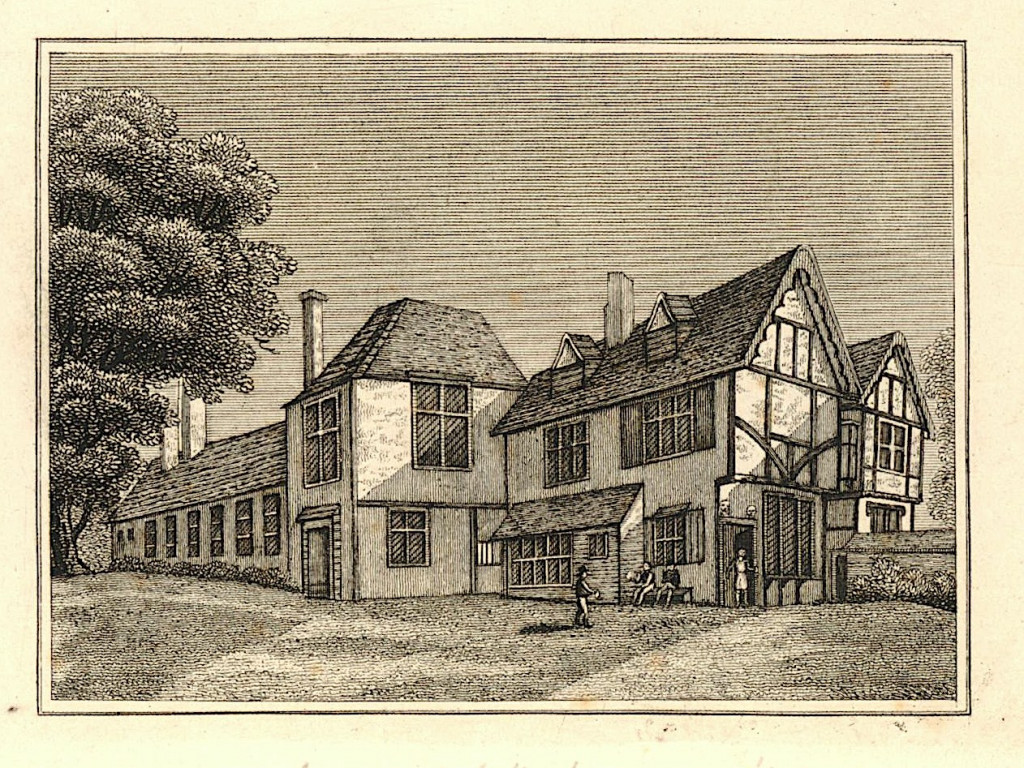

As we have seen from the blog on Austin Friars, Cromwell was proactive in renovating and upgrading any property that came into his ownership. Although the documents give no visual description of the house, VCH states that a reference to the property in the 1790s refers to ‘an ancient wooden mansion’. The conclusion is that Cromwell’s house in Tudor Stepney was at least partly timber-framed and not built of more fashionable red brick. I have only found one black and white image, claiming to be that of ‘Dean Colet’s house’ in the Victoria County History. This documents that the building survived into the nineteenth century (shown below).

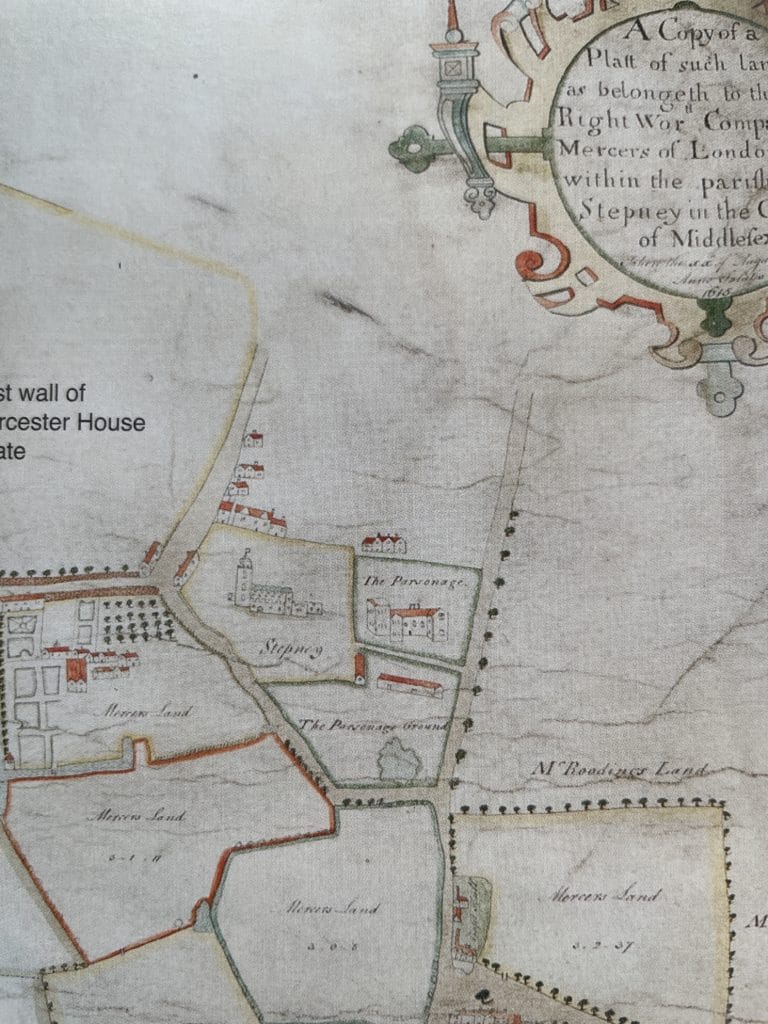

As we can see, this house is indeed timber-framed. We cannot tell if this is only a surviving fragment of the building or whether it was the entire house. As it is, it feels as though it would be a little on the small size for a man of Cromwell’s ambitions! However, a plan of the Mercer’s land in Stepney, dated 1615 (held by the Mercer’s Company) shows the most prominent building on the plot had a double-gabled roof (as we see here). It was surrounded by a cluster of 6/7 separate buildings and an orchard and gardens. Frustratingly, I have been unable to find more details about the extent or layout of the house. One thing is for sure: Cromwell was not content with the house he had taken over.

We can learn something of Cromwell’s assiduous application to the task of aggrandizing his principle houses, including Austin Friars and Stepney, from a flurry of letters exchanged between Master Secretary Cromwell and his Comptroller of the Household, Thomas Thacker, in the summer of 1535. This was the summer of the historic 1535 progress when Anne Boleyn spent her last summer on earth at her husband’s side. Cromwell accompanied the royal couple for part of the progress. Letters from Thacker to his master continuously refer to the current state of building works at each of his properties, not only at Stepney but at Austin Friars’, Hackney and ‘The Rolls’.

So, for example, in one letter, dated 11 August 1535, when Cromwell was over on the other side of England in residence at Berkeley Castle, Gloucestershire, Thacker writes: ‘Your households at the Rolls, Friars Austins, Hackney, and Stepneth [sic], are in good health. The stair there [I assume Stepney as he goes on to list what is being done at the other properties separately] from your lodging down to the gallery is finished with a window where the jakes was, very well done. ….Your buildings go forward with all diligence. The Rolls, 20 Aug.’

From this, we can discern that Cromwell was not content enough to suffice himself with the houses he bought or leased. He wanted properties that would adequately reflect his elevated status as one of the most powerful men in the land. Not only that but could we also infer some control freakery here? Certainly, Cromwell seems to have been ‘all over it,’ as we would say today. His capacity for work and detail, for juggling far too many balls simultaneously, was part of his genius and an essential ingredient of his incredible success.

A Sinister Invite…

Now, back to my original reason for writing this blog: the arrest and interrogation of Mark Smeaton at Cromwell’s Stepney home on 30 April 1536.

Although initially promoted at court by the Boleyns, Thomas Cromwell and Anne Boleyn had seriously fallen out by the Spring of 1536. They had quarrelled over matters of religious reform, and Anne had threatened Cromwell in several public spats; it was not a smart move. In the end, Cromwell had taken himself away from court and, according to Chapuys, ‘had planned and brought about the whole affair’ of Anne’s downfall.

We can draw upon three sources to confirm Cromwell’s presence at his manor of Stepney on that fateful day and the details of the events unfolding. The first is The Spanish Chronicle, a sixteenth-century Spanish account of the events of the reign of King Henry VIII and Edward VI. This provides us with the most detail of Mark Smeaton’s interrogation. (Note: The Chronicle is a little fanciful, to say the least, but nevertheless, it is often used as a contemporary source, and we shall do the same).

The second is a contemporary account from George Constantine, a reformist priest, who had been appointed into the service of Sir Henry Norris in the same year, 1536. Finally, Cromwell’s letter, written on the date in question, confirms his presence at the Stepney manor house. In two other letters, written in May 1536, which report on the events unfolding, Mark is described as a ‘spinnet player’ and in another ‘an organist of her [Anne Boleyn’s] chamber’.

According to The Spanish Chronicle, the account describes how Cromwell, who was ‘going to London’, sent for Mark and said,

“Mark, come and dine with me, and after dinner, we will return together.” Mark, suspecting nothing, accepted the invitation; and when they arrived at Cromwell’s house in London, before dinner, he took Mark by the hand and led him into his chamber, where there were six gentlemen of his, and as soon as he had got him in the chamber he said, ” Mark, I have wanted to speak to you for some days, and I have had no opportunity till now. Not only I, but many other gentlemen, have noticed that you are ruffling it very bravely of late. We know that four months ago you had nothing, for your father has hardly bread to eat, and now you are buying horses and arms, and have made showy devices and liveries such as no lord of rank can excel. Suspicion has arisen either that you have stolen the money or that someone had given it to you, although it is a great deal for anyone to give unless it were the King or Queen, and the King has been away for a fortnight. I give you notice now that you will have to tell me the truth before you leave here, either by force or good-will.”

The account goes on to describe Cromwell’s menacing questions, culminating in torture with a ‘rope and cudgel’ that was tied around Mark’s skull when Master Secretary did not get the detail that he was looking for. He wanted a confession from Mark that he had slept with the queen. This detail was crucial in implicating Anne Boleyn in adultery and ensuring her downfall, for if he was not successful, it would have undoubtedly been Cromwell’s neck on the block. In the end, poor Mark ‘confessed all’ and was taken to the Tower. The downfall of the Boleyns would rapidly follow.

Most modern accounts of Mark’s arrest state that he was interrogated at Cromwell’s house in Stepney, citing The Spanish Chronicle as the source. However, as you can see here, The Chronicle only states that he was taken to Cromwell’s house in London. This surprised me, so I searched for where this connection to Stepney might have come from.

It is George Constantine’s account that confirms the precise location. In it, we read that ‘The first that was taken was Markys, And he was at Stepneth in examinacyon on Maye even [30 April]. I can not tell how he was examined, but apon Maye daye in the mornynge he was in the towre.’

A letter written by Cromwell on the very day of Mark’s arrest confirms his presence at Stepney on the day preceding the May Day joust, that is, 30 April 1536. The letter is from Thomas Cromwell to Stephen Gardiner and written by Thomas’ secretary, Thomas Wriosthesley. It states:

‘He will receive with this the King’s letters containing certain overtures made by the French ambassador, with the King’s answers and instructions for Gardiner how to proceed. His servant Massy arrived on Friday with his letters in cipher, which will be answered, if necessary, in the next post. Sends certain cramp-rings for his friends in France. Stepney, 30 April. Signed.’

And so we conclude our tale – for the time being, at least! Researching this blog has helped me to visualise clearly one of Cromwell’s other principal houses, acquired when he was at the height of his power. However, I leave with one unresolved question.

This is an unquenched desire to know more about what the ‘Great Place’ looked like – and perhaps I will never know. But for now, I know much more about Tudor Stepney and the country house leased by Henry VIII’s chief minister. Now the house has a name for me: ‘Great Place’. I can more easily imagine a happy-go-lucky and unsuspecting young man arriving for dinner, perhaps puffed up with pride at being invited to dine with one of the most powerful men in England, only to find himself amid a terrifying maelstrom of events that would all too soon see him executed alongside a Queen of England. While all this unfolded within the quiet backdrop of a well-to-do Tudor Stepney, not far away, across the other side of the Thames, as the great festivities of the Mayday joust were about to commence, time was running out for the Boleyns.

I would like to thank Natalie Grueninger, who unlocked the George Constantine source for me and helped nail Stepney as the undisputed location in which Mark Smeaton was interrogated. I would also like to thank Kate Higgins, Consultant Cataloguer at the Mercers’ Company, for foraging through the Mercers’ archives and sending me the information on the Acts of Court.

Appendix

Here are the two relevant Acts of Court in full.

Anno XVC XXXIIII

Quarterdaye holden the XVIIth daye of June.

At this Courte was oppenly redde in the face of the Courte a note of a lease sued for by the worsshippefulle Maister Crumwelle, the Kynges Secretary, of ii tenementes and certeyn clausynge, at Stebbennhuth, whiche matter was refferred to the dyscressiones of Maister Wardeins and Assistentes.

Anno XVC XXXIIII

Courte of Assistentes, holden the XXVIth daye of June where many worsshipfulle persones were presente

It is by this worsshipfull Assemble concluded, determyned, and fully agreed, that the right worsshipfull, Maister Thomas Crumwell, Secretarye to the Kynges Highnes, and oon of his mooste honnoureable Councell, shall haue a lease to hym graunted of a Mancion Place at Stebbunhuthe in the Countie of Middlesex, with two closses nowe made in oon conteynynge xij acres, late in the tenour of Sir John Aleyn, knyght, a closse of vi acres there late tenour of Robert Studley, mercer, a tenemente and a gardeyn there late in the tenour of William Gresham, mercer, with thappourtenaunces, for the terme of fyftye yeres, to be gyn at the Feaste of Saynte Mighelle tharchaungelle laste paste before the date of this presente Courte, yeldynge ande payinge therfore yerely to the sayde wardeins and Comunaltie of the mistere of the mercerye of the Citie of London, for the tyme beynge durynge x of the fyrste yeres of the sayde terme, xlvi s viij d sterlinges by yere, at two termes of the yere, that is to wyte, at the Feastes of Saynte Mighelle tharchaungelle and thaunciacion of our Blessed Ladye Saynte Marye, the virgin, by even porcionces. And after the sayde terme of x yeres ended & determyned to paye yerekye tio the sayde Wardeins and Comunaltye & theyre successoures vj li xiij s iiij d at the feastes abouererhersed by even porcions durynge all the rerme of xl, yeres than next ensuynge, at the whiche conclusion hadde with the saide Maister Crumwell in the premisses was by consente of this saide Courte the worshipfull Sir John Aleyn Knyght, Sir Raufe Dodmer knyght, Maister Raufe Warren Alderman, and Rycharde Gresham.

Sources

Sources that I have found most useful in writing this article:

Stepney Green: Moated Manor House to City Farm, by David Sankey and Published by MOLA

A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 11, Stepney, Bethnal Green. Originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1998.

The Spanish Chronicle, by an unknown hand.

3 Comments