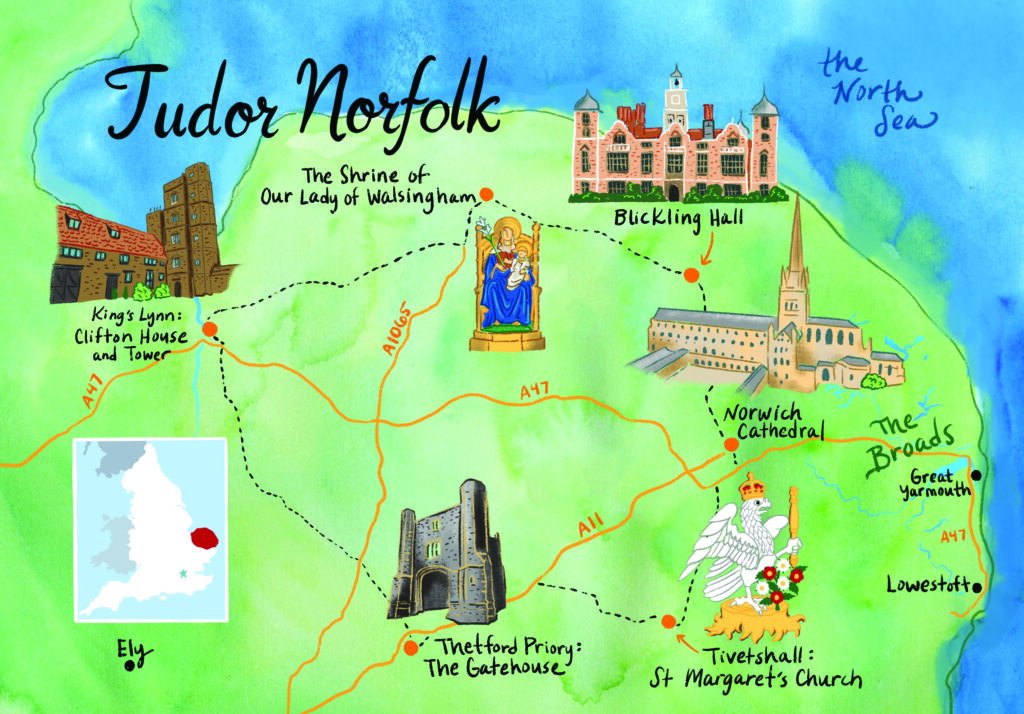

A Long Weekend Away in Tudor Norfolk

Norfolk is a county steeped in significant Tudor history. At its centre is the city of Norwich, once England’s second-largest and wealthiest city after London. Its eminence was built on its thriving cloth trade, and it was here that the Boleyns established themselves and began to amass their fortune.

As a result, not only can Norwich boast a fascinating array of medieval, Tudor, and Boleyn treasures to uncover, but the wider country does not disappoint. From the home of the Boleyns at Blickling to the ruined Howard Mausoleum at Thetford, there is plenty to explore.

We take a circular tour of Tudor Norfolk, beginning and ending in Norwich, along the way taking in numerous locations across the city and some county-wide places of historic interest.

Once more, it’s time to hit the road and go time travelling…

So, let’s get going!

Itinerary

DAY ONE:

Norwich

By the mid-sixteenth century, Norwich had become England’s second-largest and wealthiest city after London because of the wealth generated from its vibrant wool and cloth trade. This made Norwich a tour de force of England’s textile industry, as well as a cosmopolitan hub of commerce.

The city had close ties to Continental Europe. Many immigrants from the Low Countries fled to Norwich during the sixteenth century to escape Catholic persecution of their Protestant faith. These immigrants were often highly skilled weavers and their families. They were known as ‘Strangers’, and by 1578, nearly one-third of Norwich’s 16,000 residents were from overseas.

By the mid-sixteenth century, Norfolk was home to the largest Catholic population in England, while the number of Protestant immigrants made Norwich a hotbed of Puritanism. During the mid-1570s, the city’s incumbent bishops struggled to align its populous with Elizabeth I’s 1559 Act of Uniformity. This prompted the Queen’s well-documented progress to the city in 1578 when she lodged in the (surviving) bishop’s lodgings adjacent to the cathedral.

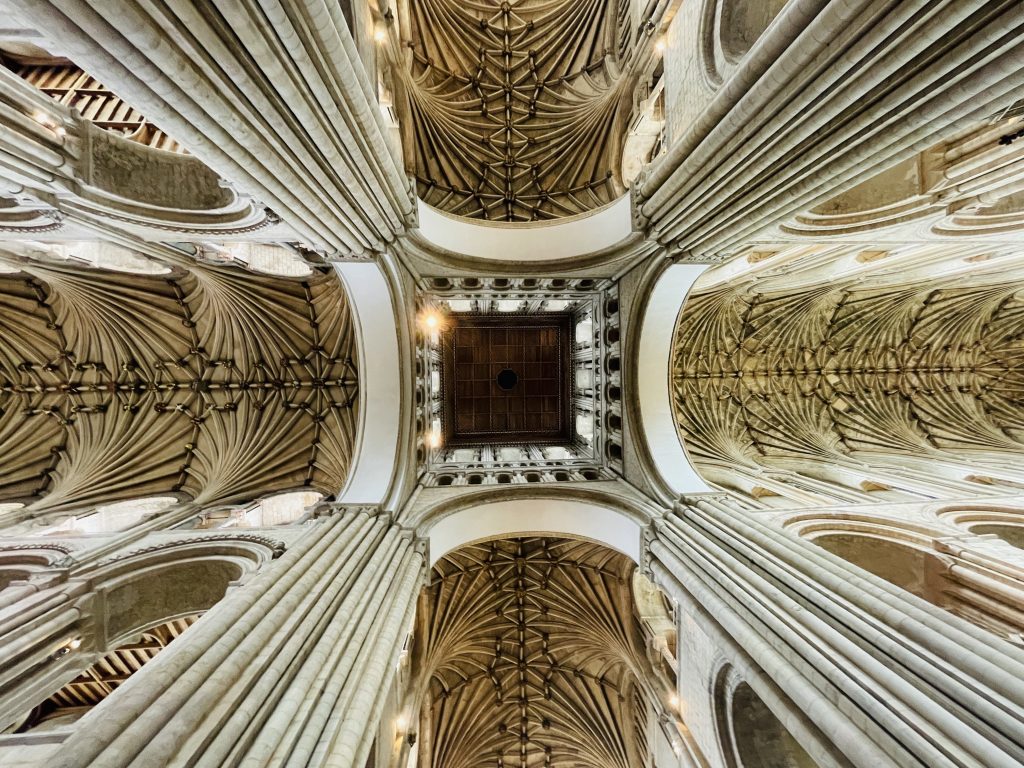

Norwich Cathedral. Images © The Tudor Travel Guide.

While in Norwich, Elizabeth I naturally visited the cathedral, where her throne was placed near the high altar, but more pointedly, directly facing the Boleyn chantry chapel, the burial place of the Queen’s great-great-grandmother, Anne Hoo.

The Boleyn family were from Norfolk. Therefore, a visit to Norwich and the surrounding area contains a number of interesting Boleyn ‘treasures’. We will visit two of these, which lie outside of Norwich, on this tour. However, for now, let us concentrate on those to be found within the city.

The Boleyn Chantry Chapel is the first of these. Standing before the high altar, you can see the Boleyn coat of arms (three bulls’ heads separated by a red chevron) running above the chantry chapels on either side of the altar.

Anne Hoo, who died 6 June 1484-5, was initially buried here. She was the wife of Sir Geoffrey Boleyn of Blickling Hall, who made the Boleyn’s fortune as a successful London mercer and then Lord Mayor of London. Her son, Sir William Boleyn, was later also laid to rest in the chapel. During the sixteenth century – Anne’s body was moved to the ambulatory that runs behind the high altar, along with her tomb ledger, where they can be found today. Sadly, her brass effigy and surrounding fittings have long since been lost.

While visiting the cathedral, don’t forget to check out its cloisters, where a splendid set of heraldic arms adorn the north wall. At the centre, you will see the arms of Elizabeth I. The original sixteenth-century murals were created to commemorate Queen Elizabeth I’s visit, although they were extensively renovated in the 1930s.

If you are a real connoisseur of the Boleyns and want to see a fragile surviving link between this famous family and the city, plug ‘King Street’ into Google maps and take the 10 -15-minute walk to see the outside of 125-127 King Street.

At the beginning of the fifteenth century, Sir William Boleyn, Anne Boleyn’s grandfather, owned this building. Although it seems to be one of the quieter parts of the city today, back in the sixteenth century, it would have been a bustling hive of activity located near the city’s quayside.

Here, highly prized wool and cloth were shipped out across Europe. While this property’s exact use is unknown, it is likely to have been connected to the Boleyns’ role as mercers or cloth traders, making King Street the ideal location to conduct their business.

While you are there, immediately next door, you will find Dragon Hall, renowned as one of Norwich’s finest medieval architectural gems. It was built in 1427 by a wealthy merchant of Norwich who became its Lord Mayor four times: Robert Topps. Like the Boleyn property, it served a purely commercial function and was a place to display goods and to trade. Today, it is well known for its magnificent crown post roof and intricately carved and painted dragon. If you wish to visit, you need to join a tour.

Stranger’s Hall. Images © The Tudor Travel Guide.

Across town is the 700-year-old Stranger’s Hall. Although early medieval in origin, significant remodelling was done through the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. It is an excellent example of a wealthy merchant’s house. Various architectural styles are on show, from the medieval undercroft to the sizable central hall, illuminated by a grand oriel window, placed there around 1539.

Like Dragon Hall, Stranger’s Hall (see images above) was also owned by well-to-do city big-wigs, including Nicolas Sotherton, grocer, alderman and later Lord Mayor of the City. He did much to upgrade the house during the early sixteenth century. The aforementioned great hall and its impressive window owe much to his efforts.

Back towards the cathedral and close to the River Wensum, you will find one of the city’s oldest, best-preserved medieval streets: Elm Hill. Its charming winding cobbled lane is fronted with many timber-framed houses. Most of these date to post-1507, when a great fire in Norwich ripped through the city, destroying 700 houses. The only medieval house to survive on the Lane is the Britons Arms, now a popular coffee shop.

The Britons Arms, the only medieval house to survive on the Lane. Image © The Tudor Travel Guide.

Just around the corner, from Elm Hill on St George’s Street, you will find another flint-faced medieval building known today as ‘The Halls’. Originally, this building was part of the Blackfriars monastery. It has a history that is intertwined with the Wars of the Roses. Edward IV, Richard, Duke of Gloucester and Elizabeth Woodville were all entertained at Blackfriars on 18-21 June 1469, while Elizabeth Woodville visited with her daughters during the following month. Elizabeth lodged at Blackfriars for one month, leaving for London only after hearing the news of the execution of her father and brother at Pontefract Castle at Warwick by the Kingmaker’s hands.

The centrepiece of these ruins is St Andrew’s Hall (once the nave of the friary church), completed in 1449. Today, it is used for civic functions, but the friary ruins are considered the best preserved in England, so they are worth a visit.

Finally, to round off our exploration of the city, we need to head out of town. Two miles from the heart of Norwich is Mousehold Heath. This open scrubland, perched high above the city, is renowned as the place where Robert Kett led the eponymous rebellion against the Crown during the reign of Edward VI. The rebels numbered 16,000 and were protesting about the enclosure of land by the gentry class. They established their camp on the heath, stormed, and took the city on 1 August 1549. Eventually, however, Kett was captured and hung from the walls of Norwich Castle.

St Margaret’s Church, Tivertshall

Tucked away in an isolated corner of rural Norfolk is our final Boleyn treasure.

St Margaret’s Church, Tivetshall, stands in splendid isolation. Locating it amidst endless open fields feels satisfying. However, once you step inside its cool interior, you will be rewarded by the sight of a rare sixteenth-century survivor, a tympanum and rood screen diving the chancel from the choir, dedicated to Queen Elizabeth I.

Such objects were ubiquitous during the medieval period. Before the Dissolution, they were decorated with religious imagery, which was later removed. The tympanum at Tivetshall is painted with Elizabeth I’s insignia, with the ‘ER’ for ‘Elizabeth Regina’ placed prominently on either side. Symbols relating to all the other Tudor monarchs can also be seen: Henry VII & VIII on the left, while the badge of the Phoenix in flames of Edward VI & and the pomegranate of Mary I are displayed on the right-hand side. Underneath the Royal Coat of Arms are the words: ‘Gode Save Queen Elizabeth’, followed by ‘Let every soul submit themselves to the authority of her powers, further there is no power but God. The powers that be are ordered of God.’

St Margaret’s Church, Tivertshall. Image © The Tudor Travel Guide.

The survival of this sixteenth-century artefact is remarkable in itself. However, more rare still is the presence of Anne Boleyn’s badge, right in the centre and underneath the aforementioned text. Here, you will see the crowned white Gyrfalcon perched on a stump, from which Tudor roses spring forth. The falcon is grasping a sceptre in one of its raised talons, a symbol of majesty.

While Henry VIII attempted to obliterate the memory of his fallen second wife following her execution in May 1536, the parishioners of St Margaret’s appear to have remained loyal to the Boleyns, whose connections to Norfolk stretched back to the early thirteenth century. It seems that ‘her poor countrymen’ defiantly refused to forget Anne Boleyn’s name.

DAY 2

Blickling Hall

Blickling Hall lies 14 miles directly north of Norwich. Today, a grand Jacobean house stands where an earlier medieval manor belonging to the Boleyn family once stood. If you believe, as many do, that Anne Boleyn was born in 1501, then this is where she and her siblings most likely came into the world.

The Boleyn home had been built by their great-grandfather, Geoffrey, who purchased the estate from his neighbour, Sir John Fastolfe, in c. 1450. According to John Leland’s Itinerary, Geoffrey built himself a substantial brick house on the site of a rectangular moated medieval house, which had been erected in the 1390s by Sir Nicholas Dagworth.

Very little is known about Geoffrey Boleyn’s brick house, as Sir Henry Hobart rebuilt it in the 1620s, and it was again remodelled in the 1760s. However, Sir Henry Hobart’s Jacobean mansion incorporated parts of the original Tudor service wing on the western side of the house, including numerous chambers, a kitchen and a porter’s lodge, which survived until the 1760s.

After the destruction of the Boleyn family in 1536, Sir James Boleyn, Thomas’ younger brother and heir, inherited the family estates and tended to them until he died in 1561. As he died with no male heir, his estate was then divided between his sister’s descendants, the Cleres, and Elizabeth I, eventually passing into the hands of Sir Henry Hobart.

Blickling Hall, DeFacto, CC BY-SA 4, via Wikimedia Commons.

When visiting the house, be sure to look out for the two eighteenth-century, full-sized wooden reliefs of Elizabeth I and Anne Boleyn housed in the great hall. The figure of Anne is inscribed ‘Hic Nata’ (born here), a reminder of the home’s close association with this important Norfolk family.

You will find St Andrew’s Church near the hall’s driveway. It contains an impressive collection of brasses, many of which belong to members of the Boleyn family. One of the most moving is that of Anne Wood, who married Sir James Boleyn. The story goes that in 1512, Anne was visiting her sister, Elizabeth, at Blickling when she went into labour. The babies pictured in her arms on the brasses indicate that she died in or soon after childbirth; what is unclear is whether or not the twins survived.

Also, note the fifteenth-century baptismal font. It is natural to wonder if this same font was used to baptise the Boleyn children.

It is frustrating that Tudor Blickling has disappeared, and yet it is strangely satisfying to visit the place where the long road to Anne Boleyn’s enduring legacy began.

DAY 3

The Shrine of Our Lady at Walsingham

To travel to the Shrine of Our Lady at Walsingham is to walk in the footsteps of several medieval kings, from Henry II up to and including three Tudor monarchs: Henry VII, Henry VIII and his first Queen Consort, Katherine of Aragon.

Throughout the medieval period, and up to the Dissolution of Walsingham Priory in 1538, this Marian shrine was one of the most important in Europe. Thousands of pilgrims travelled from all parts of the kingdom and beyond to venerate the Virgin Mary at Walsingham.

The shrine was built in the eleventh century on the orders of Lady Richeldis, who had experienced a vision in which she was transported to Nazareth to see where the Holy family once lived and where the Annunciation of the Archangel Gabriel had taken place. The vision instructed Lady Richeldis to build a similar place in Norfolk. This was done with the ‘Holy House’ later becoming a shrine and place of pilgrimage for the medieval world.

Of course, the shrine and adjacent priory were destroyed during the Dissolution. The statue of the Virgin was taken to London and most likely burned. However, 400 years later, during the twentieth century, an Anglican shrine was reestablished at St Mary’s Parish Church, Walsingham.

The main medieval pilgrimage route to Walsingham was from London, passing via Waltham Abbey, Newmarket, Brandon, Swaffham, Castle Acre Priory, and East Barsham, with the last mile starting at the fourteenth-century ‘Slipper Chapel’. This was so-called because it was here that, traditionally, pilgrims removed their shoes to walk the last mile. Many modern pilgrims continue this act of humility, and if you wish, you can still visit this chapel today and follow in their footsteps, removing your shoes to walk that final mile!

Thetford Priory

On the final leg of our tour around Tudor Norfolk, we are heading south to Thetford, whose river separates the counties of Suffolk on the south from Norfolk to the north.

Thetford Priory was established in 1103 by the Norman magnet, Roger Bidgod. It was linked to the great Benedictine Abbey of Cluny in France, whose tradition was to build ornate religious houses, and the surviving ruins attest to this rich ornamentation.

During the medieval period, the priory became the largest and most important monastic establishment in East Anglia. From a Tudor perspective, though, Thetford Priory is particularly significant as it became the mausoleum for the Dukes of Norfolk. Several of the early Dukes and their spouses were buried close to the priory’s high altar. This included the 2nd Duke (the father of Elizabeth Boleyn), who was interred there in 1514; Anne of York (daughter to Edward IV), wife of Thomas Howard the 3rd Duke, who died in 1511; and finally, Henry VIII’s illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond who was interred at the priory in 1536.

Thetford Priory. Images © The Tudor Travel Guide.

At the Dissolution, Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, petitioned Henry VIII to spare Thetford and convert the priory into a collegiate college. Clearly, he had a vested interest in preserving his family’s mausoleum. However, when this was refused, some of the Howard tombs (and their inhabitants) were transferred to St Michael the Archangel at Framlingham, Suffolk, where they remain to this day.

After the priory was dissolved, Thomas Howard retained ownership of the monastic buildings. While the two-storey Prior’s lodgings were eventually converted to a dwelling, which endured for another 200 years, much of the rest of the site fell into decay. Only ruins remain.

Today, the plan of the priory’s building can still be made out from its surviving fragments: the priory church, its two cloisters, and other claustral buildings are all evident. However, the best preserved of these are the ruins of the Prior’s Lodgings and the fourteenth-century gatehouse. Although this gatehouse is minus its roof and floors, it otherwise stands intact.

English Heritage manages the site, and you can access and wander around the ruins at any reasonable time of day, free of charge. There is enough to help you reimagine the scale of the priory and mourn the exquisite tombs which were undoubtedly lost when the priory was desecrated in the name of reform. Thankfully, of course, some of those tombs at least, in part, survive and if time allows, why not pick up Our Tour of Tudor Suffolk from Edition One and visit Framlingham to see them for yourself?

My Favourite Cafes & Restaurants:

Restaurant:

The Rooftop Gardens, Norwich: A part indoor, part outdoor dining area on the rooftop. Gives a fabulous view out towards the cathedral!

Cafe: The Britons Arms, Elm Hill, Norwich: a building that dates back to 1300s!