HolyRoodhouse: Pleasure Palace of the Stuarts

Writing a series of blogs about Mary, Queen of Scots, is impossible without talking about Holyroodhouse, also known as The Palace of Holyrood. It was one of Mary’s most favoured residences. It was the place in which she spent her first night on Scottish soil after her return from France in 1561; the place in which she married Henry, Lord Darnley, after a short and passionate romance in 1565. It also stood witness to one of the most traumatising events of Mary’s life, the murder of her friend and secretary, David Rizzio, in March of the following year.

Today, Holyroodhouse remains a royal palace, frequented by the monarch for one week each year. While the twenty-first-century palace sits on the site of the original, it has been greatly aggrandised and remodelled over the centuries. So what remains of the sixteenth-palace that the twenty-first-century time traveller can explore, and how do we follow in the footsteps of what happened on that murderous March evening? This blog delves into the origins of Holyroodhouse and its sixteenth-century history before reliving the events of the night in question through the words of Mary herself.

Note: This blog accompanies this month’s Tudor Travel Show podcast. If you wish to listen in, the link can be found at the end of this blog.

A Brief History of Holyroodhouse

Long before the current palace existed, outside the city walls of Edinburgh, there stood an Augustinian Abbey, founded by the pious King David I in 1128. From the moment of its inception, there was a strong connection with royal patronage, and the abbey was visited regularly. Initially, whenever the royal entourage visited the abbey, it is believed that they were housed in guest lodgings that were an integral part of the abbey’s monastic buildings.

Until the mid-fifteenth century, Edinburgh Castle, that imposing fortress sited at the top of the Royal Mile, had served as the main lodging for Scotland’s monarch in the city. However, development was restricted to the limited space on the summit of the craggy rock upon which it had been built. Not only that, but it was also, as one commentator stated, ‘wyndy and richt unpleasand’. Having visited the castle on a day blustery day plagued with squally showers, I can wholeheartedly appreciate that sentiment!

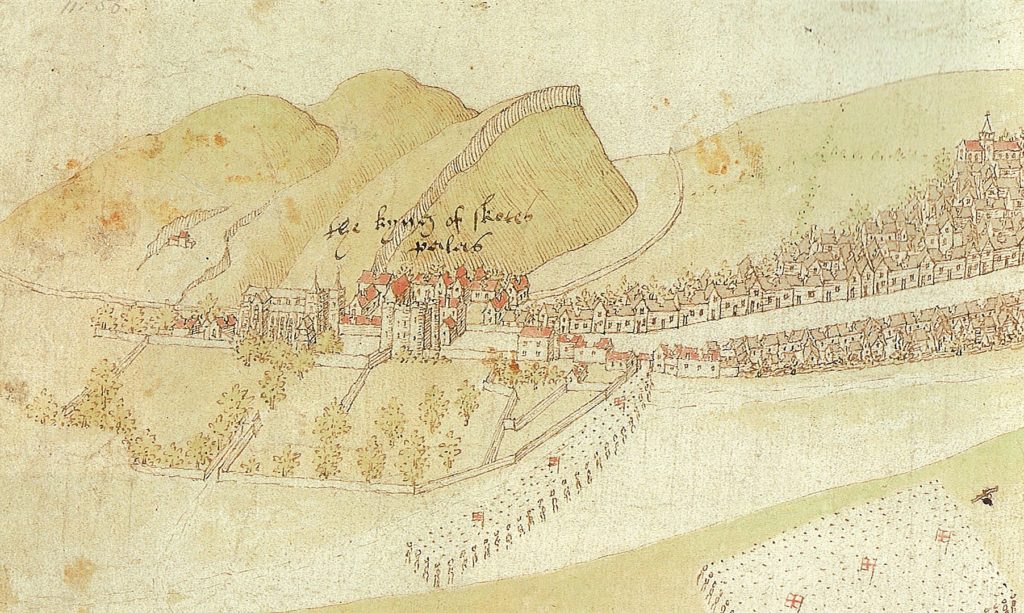

In contrast, Holyrood Abbey was sited half a mile or so outside the city wall. It was away from the press and smell of the city and had been built on low-lying land, sheltered by Arthur’s seat (see the image above) and surrounded by pleasant gardens and orchards. The appeal of Holyrood drew Scotland’s monarchs to visit with increasing frequency. So much so that by the early fifteenth century, it appears that the king and queen were lodged in a (no doubt splendid) guest lodging, separate from the abbey on a semi-permanent or permanent basis.

John Dunbar’s Scottish Royal Palaces shows this building being sited between the western range of the abbey cloisters (on the usual south side of the abbey church) and the monastic, western boundary wall. In fact, he postulates that it likely stood ‘close to the site now occupied by the great tower of James V (THE place associated with Mary, as we will hear about shortly).

James IV, Mary’s grandfather, spent a great deal of time at Holyrood. Consequently, he instigated a massive building campaign that turned the guest lodgings into what, henceforth, became known as ‘the king’s palace near the abbey of Holyrood’ from 1503 and then, by 1513, as ‘the palace of Edinburgh’. The date is significant. James was due to marry Margaret Tudor in the abbey church at Holyrood in August 1503. It seems that he was keen to have a building that was grand enough to house the reception of his young English bride. However, work at Holyroodhouse did not begin until the autumn of 1502 and was completed more than a year after the wedding.

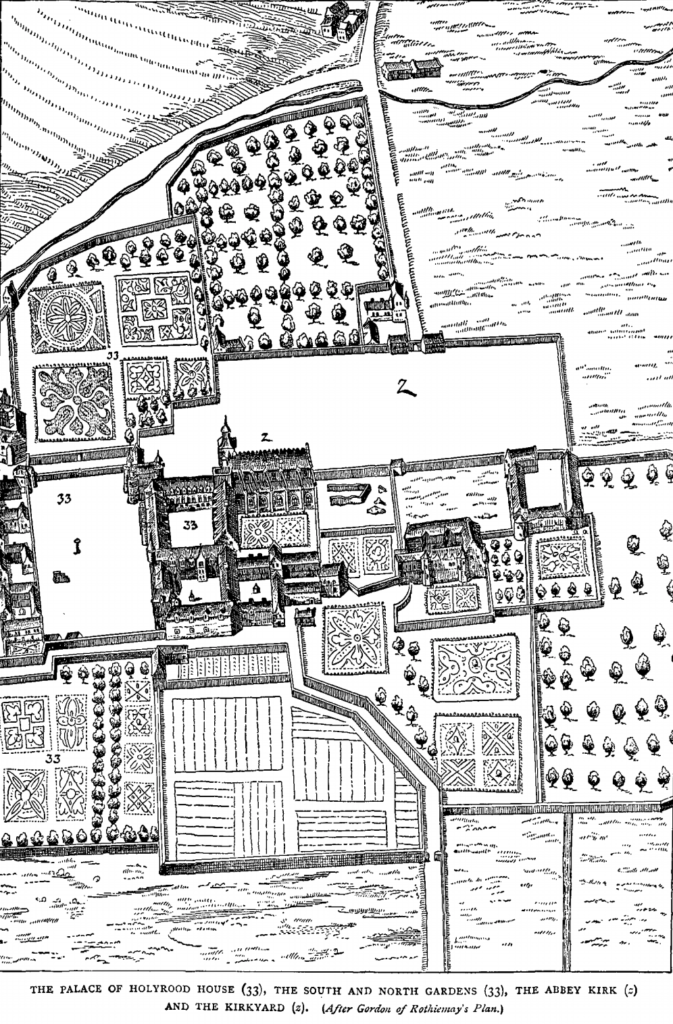

As so much of this early, sixteenth-century palace has been lost to later remodelling, the exact layout of the residence that Margaret Tudor would have inhabited is unknown. However, piecing together information from the building accounts gives us a fair idea of some of the key features of the palace floor plan at the time. James IV’s palace was built westward from the western side of the abbey cloisters to form a quadrangle of buildings around a central courtyard.

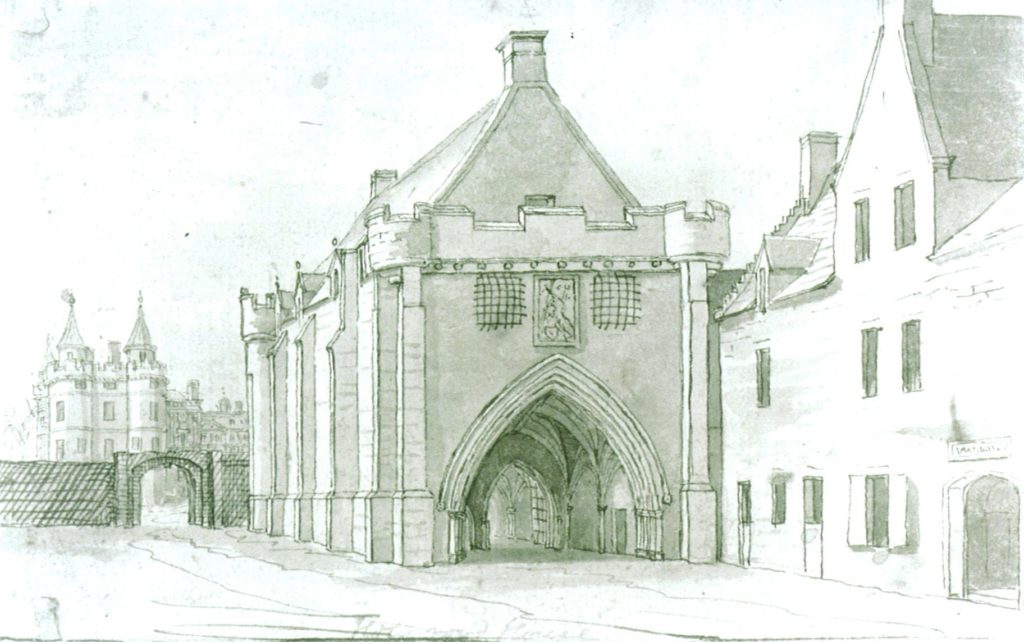

At this point, the north range of Holyroodhouse likely contained the chapel royal, the west range the king’s lodgings and the south range the queen’s. This latter range fronted an outer courtyard, or base court, which was accessed by a gatehouse (shown in the image above). Dunbar postulated that it was from windows in this south range that James IV and Margaret Tudor watched the jousting that had been arranged to celebrate their wedding. The aforementioned imprint of the building endures to this day. However, the interiors of Holyroodhouse have been significantly remodelled.

From the outset, the royal apartments at Holyroodhouse appear to have been located on the first floor. It is possible that alongside the original queen’s apartments built for Margaret when she first arrived in Scotland, a south tower, constructed in 1505, was constructed to provide additional accommodation overlooking a new south garden, which was laid out around this time. Works accounts from James V’s reign also speak of the building or rebuilding of a queen’s gallery, a lion house, a chapel, the queen’s great chamber, kitchens and a great hall, which Dunbar suggests was once the refectory for the abbey in the south range of the cloisters. Either way, Dunbar states, ‘it was large enough for the king to practice shooting in.’

James IV was, of course, killed at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. When his son, James V reach his majority in 1528, a huge campaign of the building was launched at ‘nearly all the principle royal castles and palaces’. In fact, James was and still is, known as the Renaissance Monarch because of his efforts to extensively refurbish Scotland’s royal lodgings to reflect the most swanky Renaissance fashions of the day. Holyroodhouse was no exception.

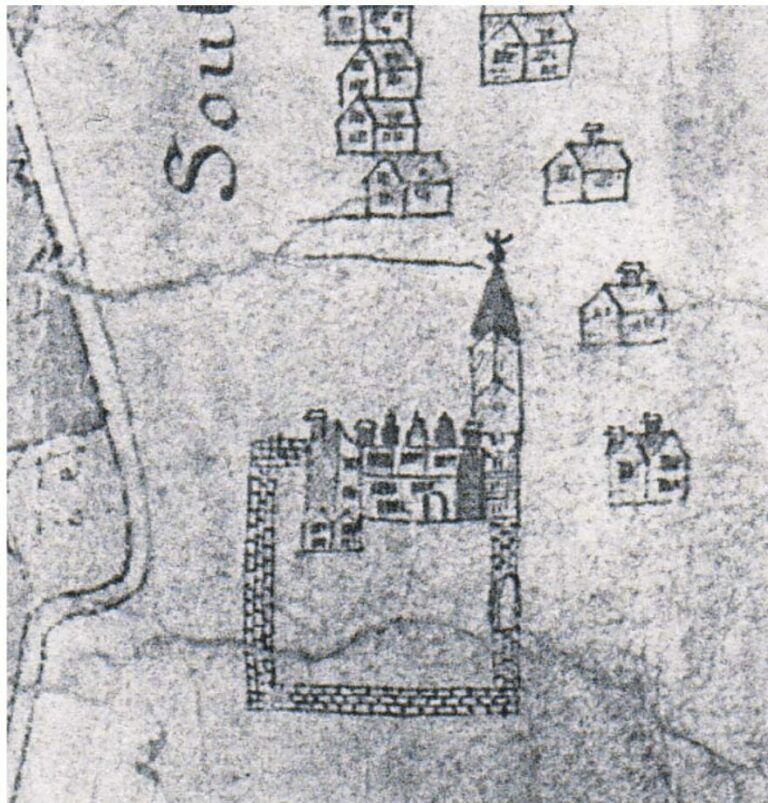

It was during this period that the large rectangular tower, which would later form the privy apartments of his daughter, Mary Stuart, was constructed between 1528 and 1532. Initially, a second tower in the southeast corner was planned in a design which would create symmetry across the south-facing range. However, the tower was never built, possibly on account of James V’s premature death. It would be his great-great-grandson, Charles II, who would complete the scheme, giving us the facade of the palace you see today. Luckily for us, a sketch of this range survives from this time from a survey of 1663 (see image below).

Building accounts relating to the erection of a new ‘tour and new werk of Halyrudhous’ are fulsome. These accounts show that the total cost of building the four-storey tower came to around £7000 – at least. A huge amount for the time. Its design echoes that of Renaissance palaces in France, with its ‘conical roofs capped with ornamental finials in the form of lions and miniature turrets, all brightly painted and gilded.’ It must have been quite a sight! The walls were lined with pine and decorated with carved panelling. Dunbar suggests that although remodelled, the ceilings on the second floor probably date from this time.

Interestingly, the original access to this tower was not as it is today. As a twenty-first-century visitor, you will find that the tower is fully integrated into the main building. However, according to Dunbar, the original arrangement was by way of a forestair (Def: ‘an external stone stair, usually to first-floor level’) in the east wall of the tower. The entrance was secured via a drawbridge and a yett (Def: a gate or grille of latticed wrought iron bars used for defensive purposes in castles and tower houses). It seems likely that this arrangement existed only until the building of the north gallery in the 1560s. There is also evidence that the Tower was initially surrounded by a moat, at least on its north side.

Within the Tower, the royal apartments are divided into two chambers on the first floor and two on the second: an outer and an inner chamber on both floors. Initially, James V’s lodgings were on the first floor and the queen’s on the second, adjacent, on its east side, to the Chapel Royal. These apartments exist, largely unaltered to this day. When Mary returned to Scotland in 1561, she occupied the rooms in this tower, and after her marriage to Henry, Lord Darnley, Mary’s private apartments were located on the second floor, with Darnley’s on the first floor. It was in these very rooms that Mary witnessed one of the most terrifying and horrific events of her life. The following makes for a thrilling read thanks to Mary’s eye-witness accounts!

9 March 1566: Murder at Holyroodhouse

The following account is based on letters written by Mary, first to the Archbishop of Glasgow and secondly to the King and Queen of France. Frank Mumby reproduces These letters in ‘The Fall of Mary Stuart‘. These documents, penned by the hand of the woman at the centre of the drama, give an invaluable and detailed insight into the shocking events that unfolded at Holyroodhouse on the evening of 9 March 1566, when Mary’s secretary, David Rizzio, was murdered in cold blood, inside her privy lodgings.

At about 7.00 pm, the queen was enjoying supper in her privy apartments on the second floor of the aforementioned tower. Mary was ‘in her cabinet, at our supper’. This small closet, measuring just 12ft by 12ft, is sited just off Mary’s Bedchamber and at the time is noted to have contained a small bed and table around which sat Mary and her guests: her half-sister the Countess of Argyll, her half brother and the Commendator of Holyroodhouse, Lord Robert Stewart; the laird of Creich; Arthur Erskine ‘and certain others our domestic servitors‘. According to Mary, Darnley then entered and ‘placed himself beside us at our supper.’

In the meantime, unbeknownst to Mary, but later recounted in the letter, ‘The Earl of Morton and Lord Lindsay, with their assistors, armed in warlike manner, to the number of 18 persons, occupied the whole entry of our palace,’ thus believing that no-one could enter or leave undetected. The first Mary knew of the revolt was the entry of Patrick, Lord Ruthven, ‘armed in like manner, with his accomplices‘. He demanded to speak with Rizzio. Ruthven was a leading member of the Confederate Lords, a dangerous group of committed protestants who were deeply unsettled by the presence of their Catholic Queen.

Mary demanded if Darnley knew of this intrusion, which he flatly denied. Of course, it would become clear that Darnley had been manipulated by the Confederate Lords to be involved in the plot by stirring up jealousy in the young lad that Rizzio was sharing more than just a platonic relationship with his wife. Mary’s husband had, in fact, allowed the Lords to gain entry to the queen’s apartments via the small vice stair with connected the first with the second floor of the tower.

Mary commanded Ruthven to leave, accusing him of treason in his persistence. It was at this point that ‘for safeguard‘, David took refuge behind Mary’s back. The 2nd Earl of Bedford, Francis Russell, who was English Governor of Berwick and occasionally acted as English Ambassador in Scotland at the time, also wrote a second-hand account of events nearly three weeks after Rizzio’s murder had taken place on 27 March. He adds in his letter to the English Privy Council that Ruthven said to Rizzio that ‘he should learn better his duty (meaning he had overstepped the mark of an acceptable relationship with the queen) and ‘offering to take him by the arm, David took the Queen by the ‘blyghts’ of her gown‘. Clearly, Rizzio sensed that this was not going to end well!

Meanwhile, Ruthven ‘cast down’ the table and ‘put violent hands on him, ‘struck him over our shoulder with hangers, one part of them standing before our face with bended daggs [cocked pistols]. Although Mary does not speak of the following, the Earl of Bedford states that Mary ‘would gladly have saved him, but the King, having loosed his hands and holding her arms’ caused the terrified David to be ‘thrust out of the cabinet through the bedchamber of presence‘. He goes on to say that initially, Lords Morton and Lindsay, who were in the latter chamber, had planned to have him hanged the next day. However, it seems the adrenaline and testosterone-fuelled encounter drove one of the rebels to ‘thrust him into the body with a dagger‘. Others followed suit. Mary merely states that they took her secretary ‘out of our cabinet, and at the entry to our chamber gave him fifty-six strokes with whinyards [short sword] and swords‘.

Mary was left traumatised and in ‘extreme fear‘ for her life. Ruthven stalked back into her chamber, hurling accusations that the Lords were ‘highly offended with [Mary’s] proceedings and tyranny,’ which they found intolerable and that they had ‘put [David] to death.’ He charged her with maintaining the ‘ancient religion [Catholicism], debarring the Lords who were fugitives and entertaining amity with foreign princes’. The ‘fugitives’ I am taking to be those loyal to Mary, which she lists in her letter as managing to escape Holyroodhouse; two of them, James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell and George Gordon, Earl of Huntley, did so by being lower out of a back window on ‘some cords’.

However, the drama was not yet over! Hearing of the ‘tumult in our palace‘, the Provost of Edinburgh and the town came ‘in great numbers‘ pressing to see Mary and to find out if she was alright. However, Mary was not permitted ‘to give answer‘. The Lords were harrying and threatening her. She reported that ‘if we desired to have spoken [to] them, they [the Lords] should cut us in collops, and cast us over the walls.’ This was treason in the extreme!

A Daring Escape…

Mary was detained overnight in Holyroodhouse. In the morning, ‘our brother the Earl of Murray‘ assembled the rebel Lords, and together, it was agreed that Mary should be moved to Stirling Castle, there to ‘approve in Parliament all their wicked enterprises, establish their religion and give the king [Darnley] the Crown Matrimonial…or else…to put us to death, or to detain us in perpetual captivity.’ Poor Mary! Yet, somehow, amidst all this life and death drama, Mary managed to keep her head. She was not going to go without a fight and already had set a plan of escape in motion. That evening (the day after the murder), she managed to speak to Darnley and persuade him that he was a puppet and had been duped by the Lords. She convinced him ‘how miserably he would be handled if he permitted the Lords to prevail. ‘ According to Mary’s own hand: ‘By this persuasion, he was induced to condescend to the purpose taken by us, and to retire in our company to Dunbar.’

In the interim, she ‘had resolved to liberate‘ herself and ‘had secretly communicated with Earls Bothwell and Huntley to devise some mode for doing so.’ This they duly did, and in a daring feat (which she would later replicate at Borthwick Castle), Mary and Darnley were lowered down from the ‘walls of our palace in a chair by ropes and other devices which they had prepared‘. Sadly, we do not know which window the pair escaped through, but Mary was free. Although heavily pregnant, she rode through the night to the safety of Dunbar Castle. One can only imagine the expletives that rang through the Queen’s Bed-chamber at Holyroodhouse when the Lords found out she was gone!

Today, you can visit the rooms in which all this drama played out; the closet, bed-chamber and chamber of presence all remain in situ, the latter containing a whole host of Mary, Stuart and other sixteenth-century treasures, not least, the Lennox Jewel which is mesmerisingly beautiful. The intimacy of these chambers holds the energy of the Scots Queen so that her presence and the dark deeds of the Spring evening are tangible beyond the veil of time. I lingered for the longest time, reflecting on this turning point in Mary’s life, for we might say that although Mary Stuart could not have known it, things would only get a lot worse from this point forth.

PODCAST: To listen to the podcast accompanying this blog, follow this link.

Sources

Sources I have found useful in writing this blog:

Scottish Royal Palaces, by John G. Dunbar.

Holyrood Abbey: The Disappearance of a Monastery, by Dennis B Gallagher.

The Fall of Mary Stuart, by Frank Mumby.

I visited Hollyrood about ten years ago twice, once on a tour, the second as private visitors. I also think we had showers both times although the second time we were lucky that while in the palace and grounds it was sunny for a few hours before more showers.

The private apartments of Mary we loved very much. The ceiling especially. It must have been a very traumatic experience for poor Mary to have her secretary murdered in front of her. Her escape and the return in triumph to defeat and then reconcile her enemies was an amazing thing. Personally I think she should have rounded up the lot of them and hung them from the castle walls in chains, leaving them for the crows. What Brutes putting the life of their sovereign and a pregnant woman in danger as well as the life of the heir.

I am not certain if it was in Stirling or Hollywood but one of them had many personal things that belonged to Mary and her father and grandparents. It was very moving to see so many items that had been touched by the Scottish Stuarts. I have also decided that there is something wrong with Edinburgh. I have been four times and three times we had showers and wind mixed up with hot sunshine. It was very odd sitting in the sun one moment and then running for shelter in Princess Street shops. The Tattoo was washed out and the poor dancers and bands were getting soaked. I think we had the only bit of shelter in the place, right at the back overlooking the city. The sunset was beautiful but the rain set in during the Tattoo. I was glad of my rain geer. We still enjoyed the tattoo and the following year we went back and the show was dry and the evening warm. It made up for the previous year. Mary is one of my heroines even though she made some curious choices of men and lost her crown. Elizabeth was wrong to execute her. She is a romantic hero but she was also a brave lady and her life was threatened by brutish men several times.

Hi! Thanks for sharing your memories. I love the way spellchecker has changed ‘Holyrood’ to ‘Hollywood’! : ) You certainly don’t visit Scotland for the hot sunny weather, that’s for sure. We had to battle with a fair few showers too!

Can we have a picture of the harpsichord please? Which was the first harpsichord I ever heard, aged 5. It used to be described as Flemish, I think, but more recently an English instrument.

I enjoyed revisiting Holyrood and its history, poor Mary. I found that shocking, aged 5!

Hi Rosalind, I don’t remember seeing a harpsichord, sadly. I love them too!