The Priory of St John of Jerusalem, London

In the [xiiijth] day of Marche [the king] toke his hors, wele and nobley accompanyede at Seitn Johns of London and rode to Waltham. The Herald’s Memoir

The Priory of St John and the Life of a Knights Hospitaller

The Priory of St John, in the City of London, was the English headquarters of the Knights Hospitallers. This was a religious order, like the Templars, that adopted a military role after the capture of Jerusalem in 1099. However, their origins predate this event.

We know that by 1080, a group of monks had established a hospital attached to the Benedictine abbey of St Mary-of-the-Latins, in the Old City of Jerusalem. Their mission was to care for the poor and the many pilgrims who became ill while travelling to the Holy Land. The community cared for anyone, regardless of their race or faith.

The Pope officially recognised this new religious order in c.1113. At this time, we see the first major establishments of the Order of St John in Europe, primarily in important embarkation ports for pilgrims travelling to the Holy Land; these included Asti and Pisa in Italy and St Gilles in the south of France.

To fully understand the workings of the Priory of St John and its subsequent relationship with the English Crown, we must remember that it was not a traditional monastery; it was the provincial headquarters of a military-religious order. So, what did that mean?

Firstly, the order received several privileges from the Pope. Importantly, their members were exempt from the authority of the local ordinaries and enjoyed extensive rights of sanctuary. In addition, priors owed no fealty to temporal authority. In other words, they answered to the Master, the head of the entire order, and, ultimately, directly to the Pope.

Members of the Order took the same vows as monks; vows of poverty, obedience and chastity, but they also vowed to ‘honour our Lord’s sick’. Because they were a military order and defenders of Christendom, their daily lives were very different to members of other more traditional, monastic orders. Your role dictated what canonical hours you were required to observe, and apart from tending to their spiritual needs, the knights also trained and worked in the hospital. Also, we know that the brethren practised gymnastics, wrestling, arms training and crossbow shooting!

The Priory was also required to pay an annual ‘responsions’ to their Convent, which was the Order’s headquarters in the east. At the time of Henry VII’s accession, this was in Rhodes. Initially, this payment represented the monastery’s entire annual income after deducting expenses. This payment later changed to about a third of their net income. Unsurprisingly, this allegiance provoked tension between the monarch and the priory’s brethren.

In the fourteenth century, the Crown imposed its sovereignty on the monastery by making any newly-appointed prior take the oath of fealty to the King. The Order reluctantly complied, which became the norm for all future Priors of St John.

The Origin and Development of the Priory

The house at Clerkenwell appears to have been founded in around 1144, during the reign of King Stephen, and on about ten acres of land, lying just north of the City walls in tranquil, open countryside. Its wealthy founders were Jordan de Briset and his wife Muriel, Lord and Lady of Clerkenwell Manor. They also founded The Nunnery of St Mary, near the north of the priory. The Priory of St Bartholomew (which I write about in one of my Tudor Travel Guides: ‘Your Tudor Weekend Away…in London‘) and the Carthusian monastery called ‘The Charterhouse’ were also nearby.

The Priory of St John thrived through the Middle Ages and soon became closely allied to the Crown. The complex’s size, the Order’s wealth, and the luxurious and palatial lodgings made it both a powerful and influential ally and an oft’ used residence for the royal family and distinguished foreign visitors.

Reconstructing the Lost Priory

Sadly, virtually all the grand buildings associated with the medieval monastery have been lost over time. All that remains today is the Tudor gatehouse, the twelfth-century crypt of the priory church, a sense of the footprint of the inner courtyard and some nearby street names, such as St John’s Lane and St John’s Square. Thus, the exact appearance of the old priory is challenging to reconstruct with any certainty.

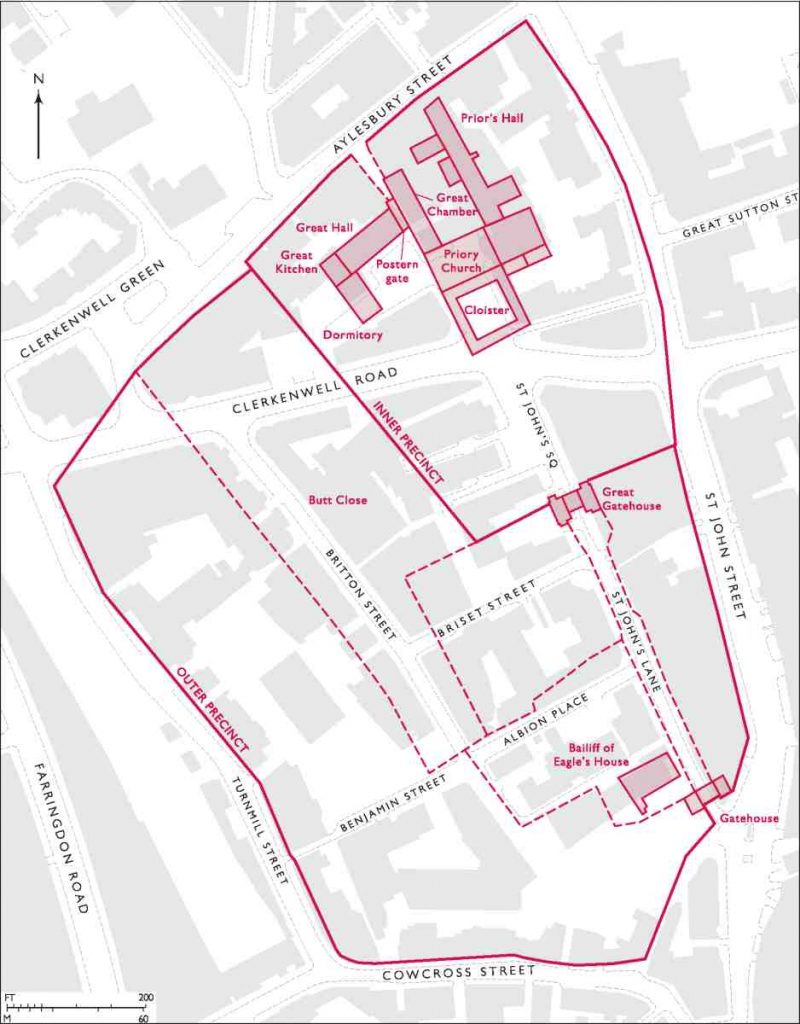

We know that the priory precincts were divided into an inner monastic precinct and an outer, secular court. An outer gatehouse gave access to the outer court. From the fourteenth century onwards, this is where officials and essential members of the Priory resided. The outer gatehouse was sited close to where St John Lane and St John Street meet today. If you walk up the modern-day St John Lane towards the Museum of the Order of St John (which is partly housed in what was once the Priory’s inner gatehouse), you are walking through what would have been the Priory’s outer precinct.

Once in the inner precinct, the Tudor visitor would have seen a complex of large halls, chambers and gardens. Perhaps only the large church, with its multiple chapels and burial ground, reminded guests that they were in a religious house, not an aristocratic mansion. Cloisters stood on the south side of the church, and to the north was situated the Great Chamber and Prior’s Hall (part of the principal lodging range). To the west were the Great Hall, the kitchens and the dormitory. The position of these buildings is illustrated in a plan drawn from British History Online. Finally, a survey conducted at the time of the Dissolution also mentions an armoury, distillery and counting house, along with a ‘schoolhouse’ and, adjoining that, the ‘Great’ and ‘Little’ Courts. The priory also boasted an orchard, fishponds, conduits, water pipes and springs.

There must have been high-status, palatial-like accommodation at the priory because, for centuries, the Order had welcomed powerful religious and royal entourages. Its illustrious list of visitors is King Henry II, King John, Prince Edward and his wife Eleanor of Castile and Richard III, to name a few. The latter chose the Great Hall as the setting for one of the most important events of his reign. There he assembled the mayor and citizens of London to refute rumours that he was planning to marry his niece, Elizabeth of York.

The Royal Progress Begins…

So now, let’s fast forward to 14 March 1486, when Henry VII, ‘nobley accompanyede’, departs for Waltham from the Priory of St John of Jerusalem. We know this was not the King’s first visit to the priory. The court had been in residence in early March, as indicated by surviving letters dated from there.

At the time, the prior was John Weston. He had previously enjoyed an amicable relationship with Richard III. However, he appears to have been eager to pledge his allegiance to the new King. In early 1486, he was one of eight men chosen to testify to the degree of Henry VII’s blood relationship with his future bride, Elizabeth of York. Weston stated that he’d known the Yorkist princess for ten years and the King since 24 August 1485. This date was only two days after Henry had won his crown at Bosworth. This fact suggests that Weston had either left London in a hurry when he’d heard of Richard’s demise or he had been in the vicinity of Bosworth at the time of the battle.

Do we know why Henry chose to depart from this location? Well, the truth is there’s no definitive answer. However, we can guess his motives. At the time of Henry’s accession, the Knights Hospitallers were already an ancient order. They had land, money and significant European connections, not to mention the support of the Pope. In the past, they’d undertaken financial and diplomatic business on behalf of the monarch, and in return, the monarch extended them royal patronage. Henry had no reason to change this. He was probably keen to garner their support.

Finally, of course, the Priory was simply very conveniently located as a starting point for a northern progress, being situated outside the city walls to the north of London and close to the main north/south highway. Once on the road, this would lead the King and court towards their next place of lodging: Waltham Abbey in Essex.

The End of the Priory of St John

Unfortunately, like other religious houses, the Priory of St John was dismantled and disbanded in 1540 as part of the Dissolution of the Monasteries. However, John Stow states in his Survey of London that the priory buildings largely remained intact during the reign of Henry VIII. However, interestingly goes on to say:

‘…the Church for the most part, to wit, the body and side Iles with the great Bell Tower, (a most curious peece of workemanshippe, grauen, guilt, and enamelled to the great beautifying of the Cittie, and passing all other that I have seene) was undermined and blowne up with Gunpowder, the stone thereof was imployed in building of the Lord Protectors house at the Strand.’

So that is where most of the Priory ended up!

Although briefly revived during the reign of the Catholic Mary I, the Priory of St. John was ultimately dissolved for good upon the accession of her half-sister, Elizabeth.

THE NEXT STOP ON YOUR PROGRESS IS WALTHAM ABBEY: Click here to continue.

Visitor Information

The Museum of the Order of St John can count itself as one of London’s best-kept Tudor secrets. For me, the incredible lure of the place is its extraordinary history and close ties with English royalty. If you love exploring places that give you room to breathe, linger and allow your imagination to take hold, then make sure St John’s is on your Tudor itinerary.

Other Nearby Tudor Locations of Interest

Oh, and don’t forget! You could easily make up a whole morning or afternoon in the area by exploring two other fascinating sites alongside this one:

The Charterhouse This was once the most important Carthusian monastery in England, latterly home to the 4th Duke of Norfolk and the scene of his house arrest.

Church of St Bartholomew the Great. This is one of the earliest churches to survive in London, with fabulous Norman architecture. Post-Dissolution, it was the London home of Sir Richard Rich.

Both are easily within walking distance of St John’s Gate, and the combination would make for an entire half-day of Tudor-themed delights. If you are subscribed at my Road Trip traveller Level, you can also see these locations as part of my 3-Day and 5-Day London Itineraries.

Sources and Further Reading

The Herald’s Memoir 1486-1490: Court, Ceremony and Royal Progress. Edited by Emma Cavell. 2009.

The Itinerary of John Leland in or about the years 1535-1543, by John Leland.

Excavations at the priory of the Order of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem, Clerkenwell, London, by the Museum of London Archaeology Service (MOLA).

The Knights Hospitallers of the English Langue by Gregory O’Malley.

Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. British History Online. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

A Survey of London by John Stow. 1603. British History Online. Initially published by Clarendon, Oxford, 1908.

Lots of new information here! Thanks for revealing those secrets ?