Nottingham Castle, Nottinghamshire

Distance Travelled from London: 196 miles.

‘The mayor and his brethren of Nottingham, in scarlet gowns on horseback with 6-700 other honest men, all on horseback received the king a mile by south Trent and between both bridges the procession both of the frerez [friars] and the parish churches received the king and so proceeded through the town to the castle.’ The Herald’s Memoir

Having left Lincoln at the end of March (probably around 29/30 March) Henry VII and his noble entourage headed in a south-westerly direction toward Nottingham. In other times, they might have lodged at Newark, but because so many were dying in the town (presumably of the plague), they did not stay there but continued on to reach Nottingham Castle.

Henry and the court lodged at the castle until ‘the next week following,’ i.e., they were there for at least a week. In fact, looking at the calendar for 1486, this puts the royal removal towards York between Monday 10 – Thursday 14 April. As there are roughly 48 miles to travel between Nottingham and Doncaster (and given the average maximum distance travelled per day was around 15 miles), there must have been at least two stops between these two towns. We know that the king was in Doncaster over a Saturday and Sunday (which must be 15-16 April). Therefore I surmise that Henry and his growing army probably left Nottingham on Wednesday, 12 April.

Nottingham Castle was one of England’s premier castles in the sixteenth century. It was on par with the Tower of London, Windsor and Dover Castles in terms of size, might and importance. Built just after the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, Nottingham Castle soon became, and remained for over 500 years, the administrative centre of the Midlands and was strategically an important location for the defence of the realm. This was because it controlled the Trent Bridge, where a major road, the King’s Highway, which connected Northampton and Leicester to York, crossed the river. This meant that throughout the medieval period, the road that passed by Nottingham was one of the main routes for the invasion of English territory from an unruly North.

Because of its importance, the castle was visited regularly by medieval kings during the annual royal progress up until the reign of Henry VIII. John Leland has left us with a fulsome account of the castle, town, and its approach from his visit in 1537, some 50 years or so after Henry VII’s first visit.

He begins by describing Nottingham as a ‘large town’. The snaking royal cavalcade drew ever closer to the city along the King’s Highway from the south. All around were low-lying meadows, including the King’s Meadows, which belonged to the castle. These often flooded when the nearby Leen and Trent rivers were in full spate. Drawing closer, on the far side of the River Leen was the ‘imposing’ town, which rose gently on the slope of a hill. However, what would have caught the eye of anyone in that train was the mighty castle perched high on a natural outcrop of sandstone, 133 ft above sheer cliffs that fell away on its south side.

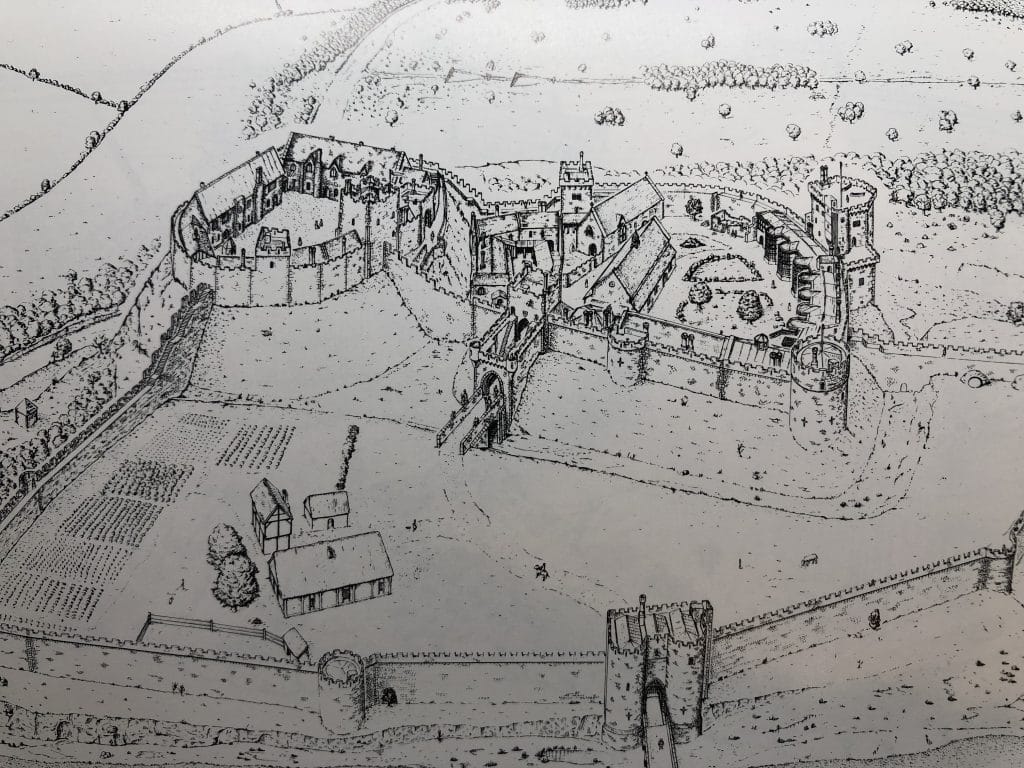

In total, the castle covered an area of approximately 10 acres. The precipitous rock formation to the west and south and man-made defences to the east and north made it, by reputation, one of the most impregnable castles in all of England.

Alongside its gargantuan scale, Nottingham Castle had a formidable and daunting history associated with extreme ruthlessness. It is recorded that in 1212, King John ‘would not eat until he had seen with his own eyes the twenty-eight Welsh hostages, sons of the most powerful and illustrious families in Wales, hung on the castle walls. These men were boys between 12-14 years. Their pitiable cries were plainly audible as they were led to the ramparts and their deaths.

Some 100 years later, it was at Nottingham Castle that the supporters of King Edward III managed to gain entrance to one of the many underground sandstone passages tunnelled out beneath the castle. They seized the king’s estranged wife’s lover, the hated Roger Mortimer, via a passage that was to become known as Mortimer’s Hole. He was subsequently taken from the castle to London to be executed at Tyburn on 29 November 1330.

For happier tales, we can look to the latter part of the fifteenth century, when Edward IV declared himself king at Nottingham. He would go on to do some of the most extensive refurbishments of the castle, creating a whole new suite of royal apartments and a grand privy tower that stretched across the entire north wall of the middle bailey. This meant that the royal family abandoned the old, medieval royal lodgings in the inner bailey. Leland eulogised about Edward IV’s ‘new’ buildings when he laid eyes on them in 1537. Around this time, the castle was said to be at the height of its glory, and he writes in his Itinerary of ‘the most bewtifullest part and gallant building…a right sumptuous place’.

It was to this refurbished castle that Henry came during the first of his three visits to the castle.

Nottingham: A Strategic Midlands Town

As we have already heard, Henry approached Nottingham from the south of the River Leen. Leland describes how the course of this river caused it to flow around the foot of the castle to the west of the town and then along the town’s south-eastern perimeter. A plan of Nottingham from around 1500 plainly shows the relationship between the castle, the town and the river. Its main access point, the Leen Bridge, is clearly seen, comprising six arches spanning several river tributaries. The Herald’s account clearly states that as was customary:

‘The mayor and his brethren of Nottingham, in scarlet gowns on horseback with 6-700 [?] other honest men, all on horseback received the king a mile by south Trent, and between both bridges, the procession both of the frerez [friars] and the parish churches received the king and so proceeded through the town to the castle.’

Escorted across the bridge spanning the Trent, the royal party would cross yet more meadows on the approach to the town before being met by ‘the frerez and parish churches’ and thence being escorted to the final bridge, spanning the Leen, which gave access to the south-west corner of the medieval town.

At the time, Nottingham was a partially walled town that was entered via one of several gates. By 1537, Leland noted that ‘much of the wall is now down, and are all the gates, except two or three.’ However, they may well have been standing in the late fifteenth century. You might imagine Henry, his nobles and his household entering Nottingham through the English Borough (on the east side of town), travelling along the High Pavement before entering the heart of the town: the marketplace.

Here, we turn to John Leland once more. He leaves us with a vivid image of what we might have seen that day. The buildings are made of timber and plaster but are ‘well built’, whilst the street is of ‘very great width, with an even, paved surface’. He concluded that ‘Nottingham’s marketplace and street [are] the finest without exception in the whole of England’…and John Leland should know, he visited most of them!

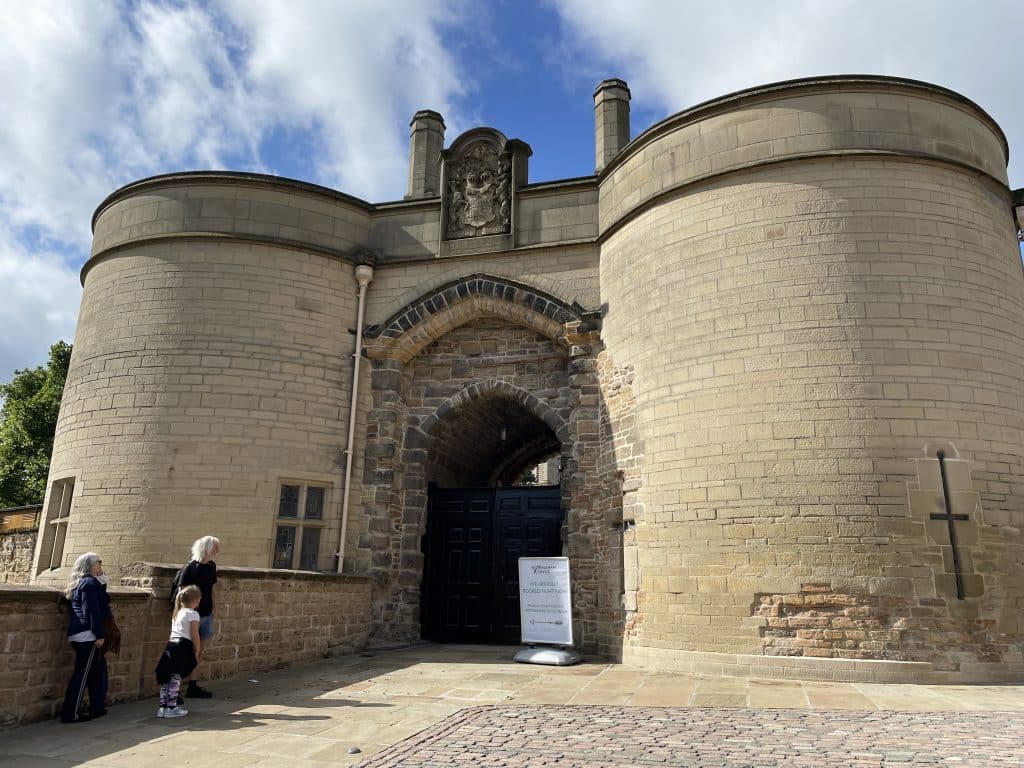

Riding atop his horse, it is entirely possible that the King may have passed through this marketplace and in front of the Guildhall to gain maximum public exposure. Brightly coloured heraldic banners would have fluttered in the April breeze amidst cheers from the expectant and curious crowds. Moving ever forward, we might imagine the royal cavalcade crossing into the street known as Castle Hill, which led, unsurprisingly, to the first of the castle gates, part of the perimeter wall. This outer gatehouse is the only substantial part of the castle to survive above ground today and gave entry to the first of the castle’s four baileys.

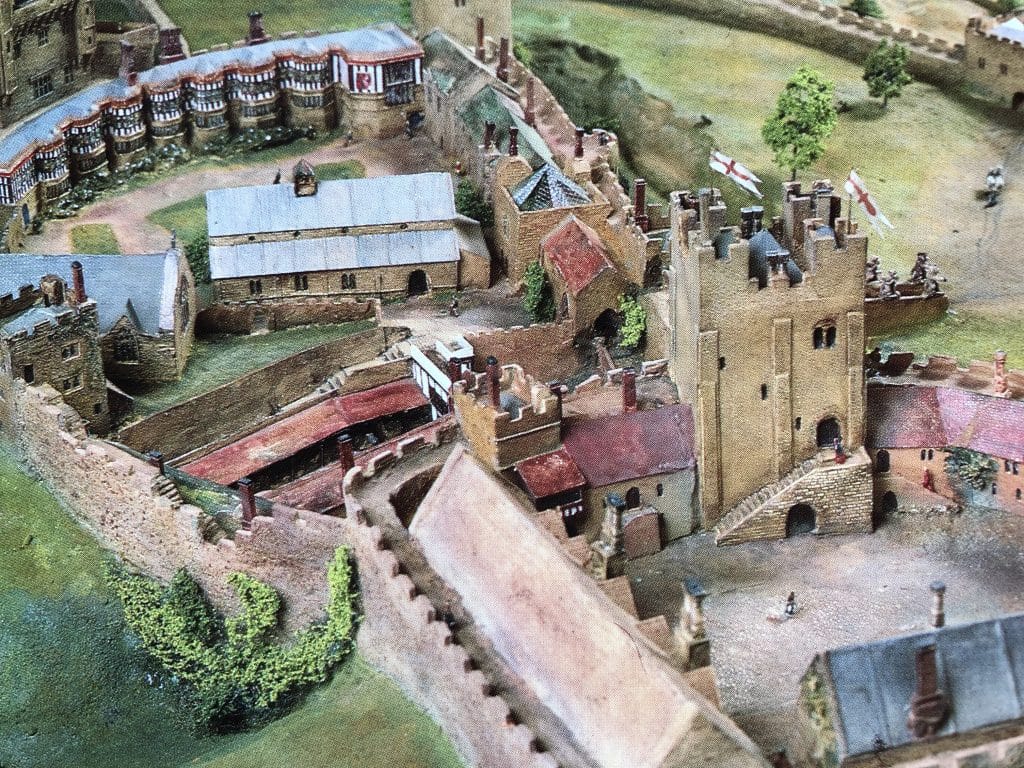

The first was the outer bailey, an ample open space containing very few buildings. It was the single largest of the castle’s four ‘courtyards’. Having crossed it, any visitor would have approached an ‘imposing bridge on pillars carved with beasts and giants’. This, in turn, led over a large ditch to reach the middle bailey via an entrance which Leland tells us is ‘exceptionally strong with towers and portcullises’.

To the north of the middle bailey were the grand, sweeping royal lodgings built by Edward IV just ten years earlier, while on the south side of the middle bailey stood a cluster of buildings arranged around what became known as the ‘middle ward’. This included the castle’s chapel. The great hall stood alone in the centre of the bailey. Finally, on the highest and most dramatic outcrop of land, the inner ward was reached by crossing a second dry moat via a bridge. This was the site of the early, south-facing medieval palace, including the keep. As we have already noted, the royal lodgings had been relocated from here to the far side of the plateau and Edward IV’s new range by the time Henry passed through the castle’s sturdy gates.

The Royal Apartments at Nottingham Castle

Having crossed the dry moat from the outer to the middle bailey, bearing right (to the north) and passing around the southern side of the great hall, any visitor would end up facing the elegant facade of Edward IV’s recent refurbishments, which Leland states is ‘an exceptionally fine piece of architecture’. According to Emery ‘the ground floor facade was stone-built…the upper floor was elaborately framed in timber’.

Following the contours of the curtain walls, the apartments are asymmetrical. A small passage bisected the range into a smaller eastern range, belonging to the king’s privy lodgings and a larger western range belonging to the queen’s side. Although only a ground floor plan now exists, Emery speculates that this arrangement was most likely repeated at the first-floor level to give a suite of lodgings on both the king and queen’s sides. However, this did not mean that the king’s lodgings were smaller than the queen’s overall, as, also accessed from this same passage via a staircase, was Edward IV’s ‘strong tower’.

This magnificent structure, which Leland called an ‘excellent goodly tower’, contained the most privy of the king’s apartments. It was a typical fifteenth century multi-angular structure intended to be resilient and be the epitome of fashionable living. It projected out from Henry II’s curtain wall, and had a hexagonal frontage consisting of at least four floors. Each floor most likely comprised one large, single chamber with a fireplace and adjoining garderobe, i.e. it was en-suite with all the latest luxuries of early sixteenth century living! Four ‘splayed’ windows set into four of the hexagonal surfaces of each room must have given breathtaking views of the western edge of the town and the surrounding countryside to the north – particularly from the top floor, the king’s bedchamber.

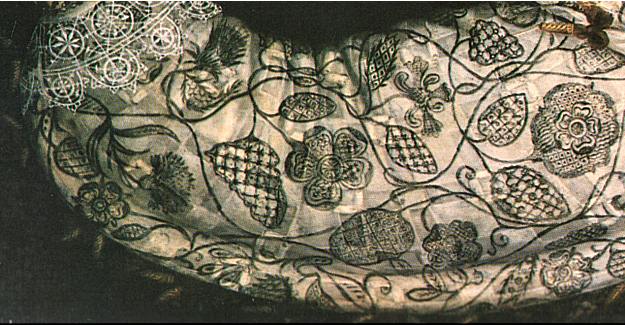

Given various archaeological finds, notably in the 1978-9 excavations, we might imagine Henry looking out across his newly conquered land through glass ennobled with paintings of the late king’s arms and emblems while he walked upon tiled floors, some plain, some decorated with patterns.

Rebellion Looms!

While the king was lodged at Lincoln, he first heard serious rumours of a rising in Yorkshire. These rumours gathered pace at Nottingham with reports that Francis, Lord Lovell, one of Henry VII’s surviving arch-enemies, was probably plotting to take York and seize the King, while his co-conspirators, the Stafford brothers, were aiming to rouse the Midlands to insurrection. Following dispatches sent out to some of his loyal nobles, the King was joined at Nottingham Castle by George Stanley, Lord Strange, the Earl of Oxford and Sir William Stanley. Although, according to Temperley’s biography of Henry VII, the King had asked the men to come unarmed, perhaps underestimating the seriousness of the rising.

When Henry left Nottingham sometime during the week of 5 April, the Earl of Derby, Lord Strange and Sir William Stanley departed company with the royal entourage for unbeknownst reasons. Although the Herald, who recorded much of what we know about the progress, is silent about the reason why the Stanleys went their separate ways, a commission dated 4 April at Lincoln suggests they had duties to undertake at Flint and Chester.

The King would return to Nottingham Castle on his return trip from York. Although the Herald does not mention it, we know he was there on 3 May, as there are records of Henry appointing the Duke of Bedford and the Earls of Lincoln, Oxford and Derby to enquire into ‘treasons, felonies and conspiracies’ in Warwickshire and Worcestershire, the epicentre of Stafford’s attempt to unseat Henry from the throne.

A Return To Nottingham & The End of the Wars of the Roses (June 1487)

The King would be again at Nottingham Castle the following year for another pivotal event of his reign. Just 18 miles or so from the town, Henry’s forces faced those of the pretender, Lambert Simnel, in the Battle of Stoke Field, on 16 June 1487. It was the final battle in the long-running saga that was known as The Cousin’s War (or The War of the Roses as we know it today). One commentator speaks of how the castle was never so grand or well-appointed as during Henry VII’s reign. However, there is no record of Henry VII spending any money on the castle at Nottingham. He felt castles were prejudicial to his government and the safety of his realm. Thus, according to an early account by Thomas Hine, it was to the ‘adoption of this policy and his parsimony that we may safely ascribe the decay of Nottingham Castle’.

By the early seventeenth century, Nottingham Castle was rapidly falling into decay. It was subsequently demolished in 1651, following the English Civil War, when Edward IV’s tower was deliberately blown up. However, the gatehouse leading to the outer bailey survived and can be seen today. At the same time, the foundations of the aforementioned ‘strong’ tower are apparently still visible in a nearby, private garden. The castle site was finally cleared in 1674, leaving behind very little trace of what was once one of the kingdom’s most important military strongholds, administrative centres and royal places.

Visitor Information (NOTE: NOTTINGHAM CASTLE IS TEMPORARILY CLOSED TO THE PUBLIC)

Today, Nottingham is a major city in the Midlands of England. Of course, with the urban sprawl of industrialisation and population growth, the town, which is estimated to have had a population of around 3000 in the mid-fourteenth century, has now grown to 320,000 (2020).

Many of its ancient buildings and landmarks, including most of the castle, have been lost. However, as is often the case, the names of some of its medieval / Tudor streets, and their position running through the centre of the oldest parts of the city, have survived. So, for example, you can still walk down High Pavement, which runs past the medieval Church of St Mary, Low Pavement and Castle Gate. The latter leads directly to what was once the outer gatehouse of Nottingham Castle.

This outer gatehouse has survived war, fire and popular revolt, giving you the only above-ground glimpse of the mighty building that once dominated the western part of the Tudor city. Of course, Nottingham Castle is infamously celebrated in folklore due to its association with the wicked Sheriff of Nottingham under the rule of hapless (and cruel) King John. Tales of Robin of Sherwood abound – the hero of local legend. Robin, so the story goes, was a constant thorn in the side of the king’s men for robbing from the rich and giving to the poor. The attractive Peter Pan-esque bronze statue of Robin, which now sits in what would have been a ditch just outwith the castle’s walls, is one of the first things that will catch your eye as you approach the gatehouse.

The long history of the castle is quite fascinating. As I have already mentioned, the main bulk of the castle was destroyed deliberately following the Civil War. This meant that it could not be used in anger again against the State. At the same time, most of the rest of the castle’s buildings were deliberately cleared away in the seventeenth century when the Duke of Newcastle built a stately home on the site of the castle’s original medieval keep. However, this house was subsequently torched by a rebellious crowd in 1831. By the end of the nineteenth century, the ruinous home of the Dukes of Newcastle was handed over to the city and turned into the country’s first municipal museum of art.

Today, this building is now part-museum (which tells the story of Nottingham and its castle) and part art gallery, containing a very fine cafe with an outdoor terrace. This terrace has some spectacular, far-reaching views of the surrounding city and countryside and certainly helps you understand the strategic importance and might of the castle.

The whole area that was once enclosed by the castle’s walls is open to the public. In fact, it reopened in 2021, having been closed for a few years, following a massive £31 million redevelopment project by the City Council. Tickets can be purchased from the visitor centre onsite.

As you wander around the gardens, make sure you look out for the imprint of Edward IV’s royal apartments outlined on the ground. This can be found on the upper terrace, in the grassy area opposite the castle museum. The curvature and extent of this range are clearly visible.

While you are there, although unrelated to our Tudor story, you may well want to explore Nottingham Castle’s underground caves, including the celebrated Mortimer’s Hole, from which Roger Mortimer, the hated lover of Queen Isabella, was abducted and dragged ultimately to his brutal death in London.

Finally, do check out the castle’s website for the latest events. Historical re-enactments are held from time to time and are superbly entertaining and educational.

THE NEXT STOP ON THE PROGRESS IS ‘DONCASTER’. Click here to continue on your way.

Nearby Locations of Tudor Interest:

Wollaton Hall (3-4 miles) If you are interested in Elizabethan Prodigy Houses, you might want to visit Wollaton Hall, which can be found 3-4 miles to the west of the city centre.

Wollaton Hall was built between 1580 and 1588 for Sir Francis Willoughby and is believed to be designed by the Elizabethan architect Robert Smythson, who had by then completed Longleat in Wiltshire and was to go on to design Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire. The hall is owned by the local Council. Check out the website here.

Southwell Minster (15 miles) Southwell Minster was founded in 627 and was initially owned by the Archbishops of York. In the adjacent archbishop’s palace, Thomas Wolsey briefly stayed after his exile from court. For more information click here.

The Battle of Stoke Field Battlefield Walk (16 miles) You can walk the battlefield trail around the decisive landmarks associated with Henry VII’s final battle of the Wars of the Roses. Access my blog and podcast related to this walk here.

Derby Cathedral (16 Miles) Visit the Derby Cathedral to see Bess of Hardwick’s tomb.

Sources and Further Reading

The Herald’s Memoir 1486-1490: Court, Ceremony and Royal Progress. Edited by Emma Cavell. 2009.

The Itinerary of John Leland in or about the years 1535-1543, by John Leland.

Nottingham Castle: A Place Full Royal, by Christopher Drage

Henry VII, by Gladys Temperley

Nottingham, its Castle, a Military Fortress, a Royal Palace, a Ducal Mansion, a Blackened Ruin, a Museum and Gallery of Art, by Thomas Hine.

Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, by A. Emery

One Comment