Venison Pie: A Christmas Tudor Treat

Christmas is fast approaching and after the end of a difficult year for most of us, some feasting and merriment will be most welcome. Well, in this month’s Great Tudor Bake Off, Brigitte Webster, our Tudor chef, here at The Tudor Travel Guide, treats us to a savoury Tudor dish for the dinner table: Tudor venison pie. We hope you enjoy reading this blog and have a go at recreating this dish for yourself. At the very end, you will also find a link to a video, where you can learn more about Tudor food at Christmas from Brigitte and follow along as she prepares the venison pie in her kitchen at the Old Hall in Norfolk. Merry Christmas!

Feasting at a Tudor Christmas

Before the Reformation, Advent, or the forty days of St Martin, was a period of fasting which ended on Christmas Eve, 24 December. Celebrations and festive food started to be served for twelve days known as Christmastide. Advent fasting meant no meat, cheese, milk or eggs. After such a long time of food restrictions, the first feast on Christmas Day would have been a very welcome arrival. The custom of eating high-value meats and other luxurious foods continued at Christmas and survived the test of time and the influence of the Reformation movement.

The staple dish of a Tudor Christmas was meat. If Christmas fell on a fasting day such as a Friday, the Church gave special permission that meat, instead of fish, could be eaten. (No such dispensation applied to New Year’s Day.)

Household accounts give us precise quantities of just how much meat was consumed. On Christmas Day 1551, at Ingatestone Hall in Essex, Sir William Petre’s family consumed six boiled and six roast joints of beef; a neck of mutton; a loin of pork; a breast of pork; a goose and four coneys. For supper, the feast continued with five more joints of mutton; a neck of pork; two coneys; a woodcock and a venison pasty.

Henry Willoughby gave a feast for all his tenants on Christmas Day in 1547 and his household accounts show the purchase of 4 pieces of beef; a whole mutton; ten geese; nine pigs; six capons; a swan; sixteen coneys; three hens; two woodcocks and sixteen venison pies! The Earl of Rutland was quite well known for having his baked stag and deer pasties sent from Belvoir when he was in London.

Venison and the Tudor Table at Christmas

Venison was the meat of the nobility and generally could not be purchased – you either were ‘gifted’ it or you had your own deer park (= forest), which supplied you with both hunting, fun and venison. Christmas fell right in the hunting season and so venison was clearly a popular choice. Most recipes call for it to be boiled or roasted and baked as venison pie. A sixteenth-century English physician and former Carthusian monk esteemed it ‘gentlemen’s food’ and felt that nowhere in the world was venison so esteemed as in England.

Some meat, such as chicken and rabbit (coney), were subject to price hiking in the run-up to Christmas before dipping to well below average during Lent. At Ingatestone Hall, rabbits featured prominently both at dinner and supper over Christmas 1551-52. This may indicate that household heads treated their servants and labourers to rabbit meat at Christmas.

Accounts between 1500 and 1600, reveal that sausage was also becoming more popular with the gentry at Christmas. Also, it has to be also that some vegetables were increasingly popular in the late sixteenth-century. This is reflected in household accounts and cookery books aimed at the well to do. A popular one was the turnip, which could be purchased during the cold season. Food (such as capons and oranges) was a popular and welcome Christmas gift.

Henry VIII received six kinds of cheese from Suffolk on New Year’s Day 1538, witnessed by Master John Husee. In 1544, Mary received sweetmeats, amongst many other gifts. Elizabeth I was the lucky recipient of a pair of quinces and a chessboard made from marchpane from the master Cook, as well as boxes of sweetmeats and crystallised fruit from the Clerk of the Spicery. In 1577-8, she also received a pot of green (fresh) ginger and orange flowers from Doctor Maister; a few marchpane from the Master Cook; a great pie of quinces and wardens from the Sergeant of the Pastry, while Morgan, the Apothecary, sent three boxes of ginger candy, another of ginger and a third filled with orange candy.

Christmas was a time when, by tradition, the wealthier members of society were supposed to extend their hospitality to those less fortunate. In December 1555, diarist Henry Machyn, recorded that he and his neighbours were guests at a great feast and offered marmalade, gingerbread, fruit and jelly.

Neighbours expecting an invite to the party at the ‘Big House’ would send anything from preserves, fruit, pies, cakes, eggs, cheese, spices, meats or brawns. From most of the records available, it seems that gifts were given in the hope either of a return of money, gold or an invitation from the local lord of the manor or sometimes as a bribe. It was also the custom for tenants to send presents to their landlords such as capon, brawns, pigs, geese, rabbits, partridges, sugar loaves, nutmeg or baskets of apples, eggs or pears.

The most iconic and beloved Tudor dishes served at Christmas were:

Mince pies made from shredded leftover mutton (shepherds), suet, sugar, dried fruits, and spices, were supposed to contain thirteen ingredients, symbolising Christ and the Apostles. Sometimes these pies were gilded. That and the spices used, proclaimed the status of the host and also harked back to Magi. It was apparently considered unlucky to cut a Christmas pie with a knife.

Plum porridge, later called Plum Pudding or Christmas Pudding and served as an appetiser, was a thick broth of mutton or beef with plums, bread, spices, dried fruit and wine. (In the Elizabethan period, flour was also added.)

Figgy pudding was a kind of sweet dish made from almonds, wine, figs, raisins ginger and honey.

Brawn was very salty pork or boar served with mustard and was available to most people.

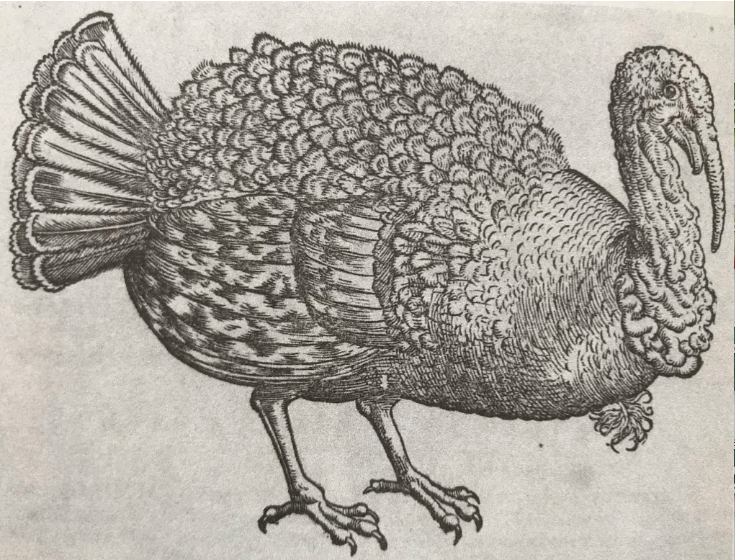

Turkey started to appear in England during the sixteenth-century. The earliest record relates to six birds imported and sold in Bristol for 2d in 1526. The new arrival started to be recognised during the 1530s, was being sold in markets in 1540s and, by the end of the 1500s, it had started to appear as a Christmas food. William Strickland, a navigator, was granted a coat of arms in 1550 showing a turkey.

Stuffing, known as forcemeat, containing egg, currants, pork and herbs, was first recorded being served with poultry in 1538.

Brussels sprouts were first recorded in 1587. As there is no English recipe from the sixteenth-century featuring them, it is very doubtful that they would have been part of a Tudor, Christmas dinner.

Twelfth Night Cake was a type of sweet bread with spices and dried fruit. Sadly, no original recipe for this survives.

Bean cake appears to have been some kind of gingerbread and was also known as peppercake. Inside there was a coin or bean and sometimes also a pea. The couple who received the slice containing the bean and the pea, were made King and Queen of the Bean. They then lead the singing and dancing.

Lambs Wool & Wassail Bowl (= I give you health) are both spiced, ale based seasonal Christmas drinks with roasted crab apples swimming on the top. The word wassail occurs in extracts from Spenser, Shakespeare and Ben Johnson.

Boar’s head is mostly associated with Queen’s College in Oxford (where it has been served since 1341). Boar’s head is a true status symbol and the King of France sent Henry a Christmas gift of wild boar pate.

Frumenty was an extremely popular side dish served with venison. Frumenty is wheat boiled in milk or ale with eggs, fruit, spices and sometimes sugar, cream or almond milk.

No feast day went without its banquet – and that was especially true of Christmas. Banqueting stuffe was a dessert course with a variety of treats on offer: sweet meats (canapes) such as suckets (fruit in syrup, marmalades etc); comfits (sugar-coated seeds & spices); marchpane; sweet breads such as Twelfth Night Cake and biscuits (or jumbles).

Tudor Venison Pie

As our main ingredient this month is venison, which we will bake as venison pie, here is an anonymous poem of the fifteenth century:

“Then comes in the second course with mickle (much) pride,

The cranes, the herons, the bitterns, by their side

To partridges and the plovers, the woodcocks , and the snipe.

Furmity (Frumenty) for pottages, with venison fine,

And the umbles (entails) of the doe and all that ever comes in,

Capons well baked, with the pieces of the roe,

Raisins of currants, with other spices mo(re).

The Recipe for Venison Pie:

“To Bake a Red Deare” from The Good Huswife’s Jewel by Thomas Dawson; 1585/96/1610

“Take a handful of time, a handful of rosemarie, a handful of winter savorie, a handful of bay leaves and a handful of fennel. When your liquor seethe and you perboyle your venison in it, put in your hearbes also, and perboyle your venison until it be halfe enough. Then take it out and lay it upon a faire boorde that the water may runne out from it. Then take a knife and pricke it full of holes and while it is warme have a faire traye with vineger therein and so put your venison in from morning vntill night, and ever nowe and then turne it upside downe. Then at night have your coffin ready. This done, season it with synamome ginger, and nutmegges, pepper and salte. And when you have seasoned it, put it in your coffin and put a good quantitie of sweete butter into it. Then put it into the Oven at night when you goe to bedde. In the morning drawe it forth and put a saucer full of vineger into your pye at a hole in the toppe of it, so that the vineger may runne into everie place of it, and then stop the whole againe and turne the bottome upward. And so serve it in.”

Here is a modernised, simplified recipe for venison pie, along with the ingredient list:

- 1 pack of ready-made shortcrust pastry for the “coffin”

- 1 small venison steak per person

- 1 tablespoon of each: thyme, rosemary, winter savoury, bay leaves and fennel

- Enough stock to submerge the meat

- 1 cup of mild (or watered down) wine vinegar

- ½ teaspoon of each: cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg, pepper and salt

- 1-2 spoonful of unsalted butter

METHOD:

First step (one day before or several hours beforehand):

- Parboil the venison steaks in stock, together with all the herbs until they are “medium rare” but not fully cooked.

- Remove them from the water, prick with a knife several times and put the meat into the vinegar. Leave it there for several hours or overnight.

Second step (next day or several hours later):

- Roll out the pastry (coffin) and form a pie “coffin” (base).

- Remove the meat from the vinegar and season it with the spices. Chop it into smaller pieces, if you prefer. Lay them out in your coffin base. Add the butter, close up with a lid and bake until golden brown at medium heat.

- Remove from the oven and while still warm, make a small hole into the lid, spoon in some of the vinegar and turn over. Decorate and serve!

Now if you want to follow along and watch this recipe being recreated in Brigitte’s kitchen, click on the image below. If you want to read more about how Tudor Christmas traditions, you can read my blog: Hever at Christmas: Festive Traditions and Momentous Decisions : Good luck and enjoy! Have a Merry Tudor Christmas! Looking forward to seeing you back in January!

Sources and further reading:

A Tudor Christmas, by A. Weir and Siobhan Clarke

Christmas in Shakespeare’s England, by Maria Hubert

Festivals and Feasts of the Common Man 1550-1660, by Stuart Peachey

Food and Identity in England 1540-1640, by Paul S. Lloyd

Plenty and Grase – Food & Drink in a Sixteenth Century Household, by Mark Dawson

Food in Early Modern England, by Joan Thirsk

Food in Early Modern Europe, by Ken Albala

The Good Huswife’s Jewel, by Thomas Dawson (1585/96-97/1610)

Each month, our Tudor recipe is contributed by Brigitte Webster. Brigitte runs the ‘Tudor and 17th Century Experience‘. She turned her passion for early English history into a business and opened a living history guesthouse, where people step back in time and totally immerse themselves in Tudor history by sleeping in Tudor beds, eating and drinking authentic, Tudor recipes. She also provides her guests with Tudor entertainment. She loves re-creating Tudor food and gardens and researching Tudor furniture.

Each month, our Tudor recipe is contributed by Brigitte Webster. Brigitte runs the ‘Tudor and 17th Century Experience‘. She turned her passion for early English history into a business and opened a living history guesthouse, where people step back in time and totally immerse themselves in Tudor history by sleeping in Tudor beds, eating and drinking authentic, Tudor recipes. She also provides her guests with Tudor entertainment. She loves re-creating Tudor food and gardens and researching Tudor furniture.