Hever and its Stories: Passion, Intrigue and Murder!

Think you know the story of Hever Castle? Well, maybe think again! Many of us will know its principal claim to fame as the childhood home of Anne Boleyn…but of course, there is so much more to its history than that. I recently caught up with Owen Emmerson and interviewed him about his latest research to uncover the social history of the castle: who lived that and how they shaped the fabric of the building: from Tudors in the sixteenth century to the wealth Astor at the turn of the twentieth. What we find is a story filled with passion, intrigue and even murder!

Exploring Hever’s Castle’s History with Owen Emmerson

Sarah:

Hello Owen, it’s so good to be speaking to you again!

Owen:

Thank you very much, lovely to be back.

Sarah:

And once again we are going to be talking about Hever. We’ve been speaking over the past few months and you’ve been telling me about some new and original research that you’ve been doing on Hever Castle. So, I thought it was a great opportunity for us to get together and maybe delve into that in a little bit more detail.

Owen:

Absolutely, yes. I’m writing a book with Claire Ridgway, the historian, and having a fantastic time learning all about Hever and the people who lived there.

Sarah:

Well, I’m excited because as well as talking about Tudor Hever, you’re going to take us forward in time and share with us some of the other key events related to the castle, right the way up until its restoration and modernisation by the Astor family in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Owen:

Yes, that’s right. We’re going to skip through history and look at some key characters that people will have heard of, but also some other personalities that people may not have heard of. Indeed, I had no idea that they existed either until we started doing this research!

Hever and the Boleyns

Sarah:

We are, in fact, going to start with Hever in 1528. Of course, it was in May 1528, 492 years ago that England, and London in particular, were in the grip of the sweating sickness. This broke out in London, sending courtiers and the King fleeing in all sorts of different directions to their country properties. Maybe here we can pick up the story of Anne Boleyn and her family at Hever. Can you tell us a little bit more about the events around the sweating sickness and the role that Hever played?

Owen:

Yes, absolutely. I think Hever is often remembered as being both the childhood home of Anne Boleyn and also, of course, as the famous location where Henry VIII courted her, but Hever also plays a very crucial role in 1528 when it was a place of quarantine for the Boleyn family.

Now I’m sure in the age of COVID-19 people could think of worse places to be locked down in than at the beautiful Hever Castle, however, during the Boleyns time in lockdown they were, in fact, gravely ill.

The sweating sickness was first identified as such during an outbreak in 1485. There were several outbreaks of the disease throughout the Tudor era. For example, there was an outbreak in 1508, one in 1517 and then, after the outbreak, we are going to talk about in 1528, there was another in 1551. It was a frightening and deadly disease.

Sarah:

Can you tell us more about the symptoms?

Owen:

Unsurprisingly, there was profuse sweating as a result of a high fever; great thirst; redness of the skin; a pounding headache and breathlessness. There was also this overwhelming desire to sleep. It was that desire that was synonymous at the time with a high likelihood of fatality. People seemed to drift quickly into unconsciousness and could die as quickly as within two hours.

Now there has been some confusion in the past as to which of the Boleyn family actually contracted the sweat in 1528. And while there’s been no doubt that Anne herself contracted it, there has been some confusion as to whether George or Thomas (or both) were infected.

Sarah:

Can I just ask you, Owen, just for those people who aware, where is the evidence that starts to point towards who was involved and who was affected by this disease?

Owen:

Our best source would be The Letters and Papers of Henry VIII. from these, I believe that we can clearly determine that both George and Thomas were very ill with the disease.

We know that the first signs of the breakout in 1528 comes when one of Anne’s maids was suddenly taken ill. As a result, Henry leaves court immediately and travels to quarantine at numerous properties, including Walton Abbey. Now Thomas doesn’t travel with the King, but George does.

We can locate Thomas at Hever before the outbreak. So, it’s very possible that he wasn’t at court at the time. We have correspondence from Thomas from Hever at the end of May; he writes to Wolsey regarding the maintenance work he’s been overseeing at Tonbridge Castle and he signs off a letter, “From Hever, Friday before Whit Sunday” which would date it to 29 May.

So, I have a feeling that Thomas is already at Hever. We also know that before 16 June, Anne is taken to Hever as a precaution. There she develops the symptoms and falls incredibly ill. It’s at this point that Henry writes a rather frantic letter to Anne (at Hever), when he discovers that she has been taken ill. From the letter, it sounds as though this news has been delivered in the middle of the night – or certainly late in the evening.

Sarah:

Very dramatic, isn’t it?

Owen: It is, yes,! If anyone would like to read it, it’s known as Love Letter eight. The original is kept in the Vatican Archives. We believe it was composed on 16 June. I’d highly recommend Sandra Vasoli’s work on these letters. She’s twice had access to them in the Vatican archives and she does such a wonderful job describing this letter. She notes Henry’s panic and how it’s strewn with ink and blots and mistakes. Actually, if you look at digitized versions (you can get them through the Vatican archives website), you can see Henry’s concern etched into the parchment of this particular letter.

It’s also in this letter that we get the now-famous snippet of information that Henry is sending his second-best doctor to attend on Anne during her hour of need. Now, I’ve even seen it used to suggest that Henry could only have loved Anne up to a point because he’s sent his second-best doctor. It’s almost been used as a measure both of Henry’s affection and his selfishness, but I think this is slightly unfair.

Firstly, I think it’s important to note that Henry is paranoid about illness. He also has a duty of care to the country to protect himself as the ruling monarch. Moreover, his letter actually makes it clear that “The physician in whom I have the most confidence is absent at the very time when he might do me the greatest pleasure.” So, in fact, Henry sending his second-best doctor, Dr Butts, because his premier physician is absent. Therefore, Henry is actually sending the best doctor he has to Anne’s side; it’s actually an incredibly selfless act when you consider that huge swathes of his court are dropping like flies. I don’t really give Henry credit for much but, on this occasion, I do think he’s done the right thing. He knows that Anne is ill.

Sarah:

He gets the benefit of the doubt. Also, and I don’t know whether you can answer this question, but if you read a lot about this period, Dr Butts starts to appear very regularly in the accounts and in letters. I wonder whether being around at this point marked out him for certain esteem and favour from this point forward?

Owen:

I think that you’re on to something there, particularly because of the good outcome that follows. We know that Henry writes again to Anne at Hever from Hudson, which is now known as Love Letter nine. This is dated to around 20 June. It’s from this letter that we get information about George; Henry writes, “For when we were at Waltham, two ushers, two valets de chambre, and your brother, Master Treasurer, William Fitzwilliam fell ill, but are now quite well.”

So, I think we can safely say from this part of the correspondence that it is George, not Thomas, who is with the King and that he had the sweat but had recovered from it by this point. We also get more information about the success of Mr Butts’ mission at Hever that comes from other correspondence. Dated the 23 June, we have correspondence from Thomas Heneage, who is Wolsey’s gentlemen usher. He writes to Wolsey to update him on the situation.

From this letter, we learn that “This morning it is told me that Mistress Anne and my Lord Rochford had the sweat and were past the danger thereof.” We also have correspondence on the same day from Wolsey’s secretary, Brian Tuke, who writes, “How Mistress Anne and my Lord Rochford both have had it, what jeopardy they had been in by turning in of the sweat before the time of the endeavour of Mr Butts who has been with them in his return and finally, of their perfect recovery.”

Sarah:

So, of course, Lord Rochford here refers to Thomas Boleyn, which I suppose could be a bit confusing because eventually, of course, George Boleyn became Lord Rochford when Thomas was elevated to the title of Earl of Ormond. However, to be clear, at this stage, we’re definitely talking about Thomas.

Owen:

Yes, we are talking about Thomas Boleyn and not his son.

Sarah:

Do we assume then that it was Anne that took the sweat to Hever and infected her father?

Owen:

Yes, I think it is highly likely. Once the sweat broke out in London, courtiers and their servants scatter to their country seats to seek clean air and refuge. I think we can also glean from subsequent correspondence that Thomas is was even more affected than Anne. Thomas seems to take quite a lot of time to recover. So, around 20 July, Henry asks Anne to “Tell your father on my part that I beg him to abridge by two days the time appointed that he may be in court before the old term.” So, he’s really asking Thomas to come back to court. However, we subsequently learn from Heneage in a letter to Wolsey that “My Lord Rochford and Mistress Anne cometh this week to court. My Lord Rochford was to have come but, because of the sweats, he remains at the home.”

Indeed, we have no correspondence that suggests that Thomas is at court before 20 August, when he writes a letter to Wolsey from Penshurst, by which time he is then the steward of the house on behalf of the Crown. It seems, though, that the family are all back at court by late August for the arrival of the Papal Legate from Rome. Thus, Thomas is absent from court for quite a long period of time, delaying Anne’s return. I find that quite an interesting detail.

Sarah:

It is, it’s a very intimate window into a relatively brief moment in time that sheds further perspective on how this virus affected the family.

Owen:

It is, and I think we can glean from the correspondence that all of the Boleyns suffered pretty badly on account of the Sweat, though none more so a that Mary Boleyn’s husband, William Carey. He, of course, lost his life during that outbreak. However, Hever acts as a safe haven for the Boleyns at a time of great turmoil and it repeatedly does so. Time and time again, Anne returns to seek sanctuary.

Anne of Cleves at Hever Castle

Sarah:

Well, let’s move forward a little bit to the other Anne of Hever Castle and that’s lovely Anne of Cleves. I know you also have a particular love for Anne of Cleves, so maybe you could tell us a little bit more about her time at Hever.

Owen:

Yeah, absolutely, she’s another favourite of mine. She’s a very, very colourful character and I’ve really enjoyed researching her time at Hever. After the very quick and dramatic downfall of the Boleyn’s, Hever became the property of the Crown. Now, it was once held that the castle was seized by Henry following Anne Boleyn’s execution. However, we do have particularly good documentation that suggests otherwise.

We know that by that time, Thomas Boleyn was a shadow of his former self. He dies in March 1539 and is buried near his infant son, Henry, at the church of St Peter at Hever. Thomas leaves ample provision for his mother, Margaret Butler, to live out her last days at Hever. She is the last of the Boleyns to live there.

Sarah:

Do you know, I remember coming across Margaret Butler many, many years ago, but still well into my love of the Tudors and suddenly having this realization that Anne had a grandmother who was alive and living in Hever! I think we tend to forget some of these other characters that lived there around that time. I’d love to know more about her; she must have been quite a character, living to a ripe age.

Owen:

She’s another one of forgotten characters, and her absence from the narrative helps perpetuate this idea that Anne comes from humble birth. People only tend to focus on the male side of the family when, in fact, Margaret Butler is the co-heiress of the Earldom of Ormond; she’s from an incredibly prestigious family! She’s from one of the premier families in Ireland and grows up in Kilkenny castle. A fascinating character!

Anyway, the estate briefly passed to Thomas’ brother, James Boleyn. He sells it to Henry VIII in 1540 in exchange for some money and, crucially, properties in Norfolk. This is the Boleyns retreating to their family seat.

Sarah:

Because, of course, they originally came from the Blickling area in north Norfolk, didn’t they?

Owen:

Absolutely, generations of Boleyns came from Norfolk. They are now more famous for being a Kentish family, but they have much, much deeper roots in Norfolk. After Henry’s ill-fated and brief marriage to Anne of Cleves, Henry bestows Hever upon her as part of her annulment settlement. However, contrary to popular belief, Anne never actually owns Hever. She was granted only the right to rent numerous properties, including the palaces of Richmond, Bletchingley and Hever. The Crown pays her rent for these properties.

That’s an awkward and important distinction, and it really means that the assets remain the property of the Crown. They aren’t, therefore, properties that she could sell or leave to anyone in her will. Now this, of course, means that Hever has really rather illustrious ownership during Anne’s tenure. It’s owned by Henry VIII, Edward VI, Queen Jane (for all of 13 days) and then by Queen Mary and King Phillip.

Anne pays the princely sum of nine pounds, 13 shillings and three and a half pence per annum to the Court of Augmentations as her rent for Hever. Anne spent much of her time after the annulment at the more auspicious properties of Bletchingley and Richmond. Unfortunately for Anne, on the death of Henry VIII, her status drops from being the King’s sister to the King’s aunt. Edward’s regency Council seem to have little time for her and they strip away her rights to lease Bletchingley and Richmond. It’s at this point that Anne begins to use Hever less as a hunting lodge and more as one of her chief residences.

Therefore, we do have references to Anne being at Hever when she writes to Mary on the occasion of her marriage to Philip of Spain. Also, Anne’s location at Hever during the rebellion against that marriage placed her, for a time, in serious danger. Wonderfully, we also have correspondence from Anne, signed from Hever to her brother. These letters provide us with some lovely little details about ordinary, daily life at Hever.

Sarah:

Oh, that’s lovely! So, her brother, of course, was Wilhelm?

Owen:

That’s right, yeah.

Sarah:

I’m just remembering that from my ‘In The Footsteps’ research! So, obviously, this was this the Duke of Cleves back in her homeland. So are those letters in the archives there? What do we know?

Owen:

Absolutely, we used to have a researcher who worked at Hever a few years ago, who was a native speaker. She was able to translate them all. So, we have a lot of translations at Hever of those letters which is just fantastic. And we get some really beautiful detailing, for example, Anne talks about her love of the honey at Hever which, I think, must mean that she’s spending a portion of her time there. After all, she’s enjoying the local wares of the area!

Anne of Cleves and the Wyatt Rebellion

Sarah:

So what happens to her there? Is it a peaceful existence at Hever?

Owen:

Well for the most part, yes, but I’ve just briefly touched upon the fact that for a time, Anne is in serious danger and it’s not a danger that she’s necessarily aware of. So, there is a large rebellion in 1554, known as the Wyatt Rebellion, which is chiefly a rebellion against the marriage of Mary I to King Philip of Spain. The rebellion is most famous for its eponymous leader, Sir Thomas Wyatt, the younger. He’s based at Allington Castle in Kent, only 15 miles from where Anne is living at Hever.

So, this area becomes the hub of rebellion was going to launch, drawing supporters from across the country. Forces came from Sir James Croft in Herefordshire; Sir Peter Carew in Devon and the Duke of Suffolk, Henry Grey in Leicestershire. Now, of course, this was Henry Grey’s second attempt at overthrowing Mary, having been involved in the elevation of his eldest daughter, Queen Jane, to the throne instead of Mary. Tragically, these treasonous actions would seal his daughter’s fate.

But the chink in Wyatt’s armour was the involvement of Edward Courtney, who is the Queen’s second cousin. It’s believed that he was to be the candidate to marry Princess Elizabeth, who would then reign in Mary’s stead. Courtney confesses the plot to Stephen Gardiner, giving the Crown the upper hand. So they’re aware that something’s going to happen; it’s not a surprise attack.

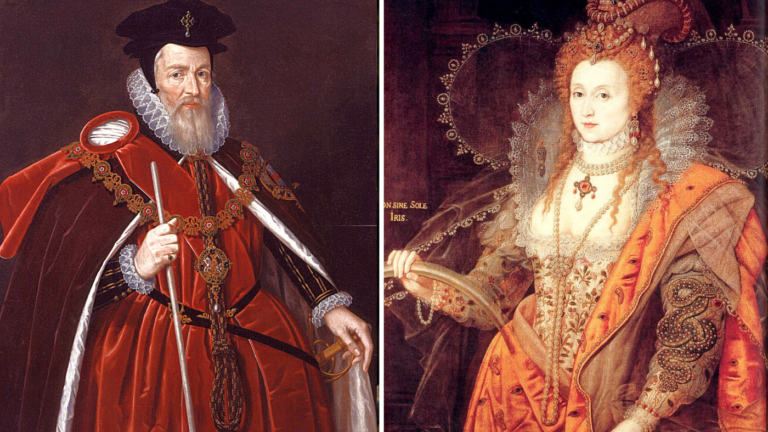

This was a rebellion, nonetheless, could have gone either way. Mary dispatches men to negotiate with Wyatt, but Wyatt would only accept custody of the Tower and the Queen in it as his terms. Unsurprisingly, these were duly rejected. Mary really shows her mettle now in a speech that she gives in her capital at the Guildhall. It’s the speech of her life really, and it clearly demonstrates how able she is to command the loyalty of her subjects. She declares that she’s married to the common wheel; very evocative of Elizabeth I’s later statement.

Sarah:

Yes, very. I was just thinking that. I was just thinking this is Mary’s Tilbury moment, isn’t it, really?

Owen:

It is and it’s so successful. It’s a truly decisive moment. It goes downhill quite rapidly for Wyatt thereafter. Mary holds her ground; she refuses to leave the court when she’s told to and eventually Wyatt is captured. So, you’re right, this is her Tilbury moment.

Sarah:

So, this puts Anne in danger because of where she’s geographically located?

Owen:

Yes, absolutely, but also because of who she is in connection with. She’s quickly implicated in the Wyatt Rebellion. According to a dispatch dated 12 February 1564, just after the rebellion, “The council has sent two of the Queen’s physicians to visit the Lady Elizabeth and find out whether she is unwell, or only pretending and whom she has in her house. And, if she is not ill, the Admirals Hastings and Cornwallis are to arrest her and bring her to the Tower. The Queen moreover told me that the Lady of Cleves was aware of the plot and intrigued with the Duke of Cleves to obtain help for Elizabeth; matters in which the King of France was the prime mover.” So, the very next sentence after Elizabeth being arrested, which of course she is, we’ve got Anne of Cleves as someone doing the moving and shaking for Elizabeth.

Sarah:

I have to say that through my writing about Anne of Cleves, I find it really hard to believe that anyone would believe that she would be stirring up trouble because she seems one of the kindest, most gentle and most submissive people at the Tudor court that ever I wrote about.

Owen:

Absolutely, it’s completely uncharacteristic. The worst Anne of Cleves does is when Bletchingley Palace is taken from her and given to a gentleman called Thomas Carwarden (who we’ll talk about shortly), she just decides to turn up anyway, even though she’s not allowed to rent it anymore. She dines at his expense and stays there regardless of his ownership of it. She’s a bit cheeky, but she’s no rebellious, Machiavellian schemer!

However, she is in an incredibly dangerous position at this point; she is close to Elizabeth, and she does have that ongoing correspondence with her brother as well as her proximity to Allington Castle. This conspires to make her a key suspect in the aftermath of the rebellion. So things are, for a time, looking incredibly precarious for Anne. Strangely, it appears that she has absolutely no knowledge of her suspected involvement or that she was implicated in it at all!

No proof is ever found that Carwarden or Elizabeth was involved, and subsequently suspicion of Anne’s involvement abated. However, Anne never regains the Queen’s trust. We have no documentation to suggest that Anne was ever invited back to court after this event. I think it’s a really tragic ending to Anne’s life because she had just regained her status with the elevation of Mary and had even been in a very respected place at her coronation.

When she died at Chelsea Manor in 1557, she does leave funds for the poor of Hever and I really think we can glean from her correspondence that she was very happy there and very fond of it. So, it’s really sad that this suspicion, which was never proven, marred her reputation towards the end of her life.

Hever Castle and its Tenant Farmers

Sarah:

Let’s move on and think about what happens to Hever after Anne dies. What can you tell us about that?

Owen:

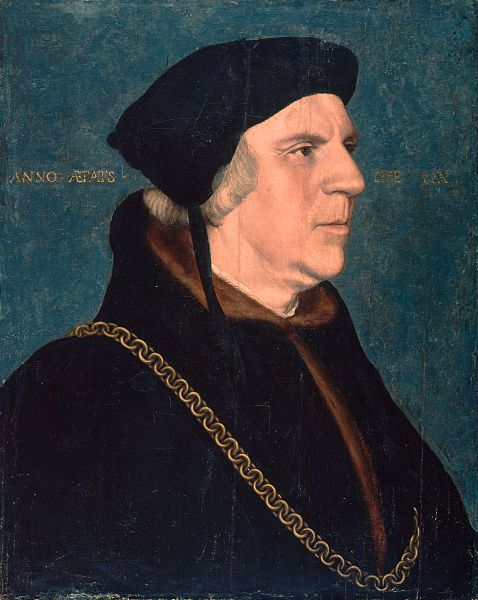

Anne’s death is really the endpoint of Hever being part of the Crown Estate. It’s sold by Mary to one of her trusted members of the council, Sir Edward Waldegrave in 1557. Visitors to Hever might recognise that name, as we do have a room so named to recognise that family’s ownership.

It doesn’t appear that any of the Waldergraves actually lived at Hever or, if they did, it was only for a very short period of time. There is a brass in St Peter’s Church at Hever to a William Todd, who died in 1585. He was a schoolmaster to Charles Waldegrave, that’s Edward’s son. This would suggest that for at least some of its history, we had some Waldegrave presence or that it acted as a sort of retirement home for valued teachers or servants; we’re not quite sure.

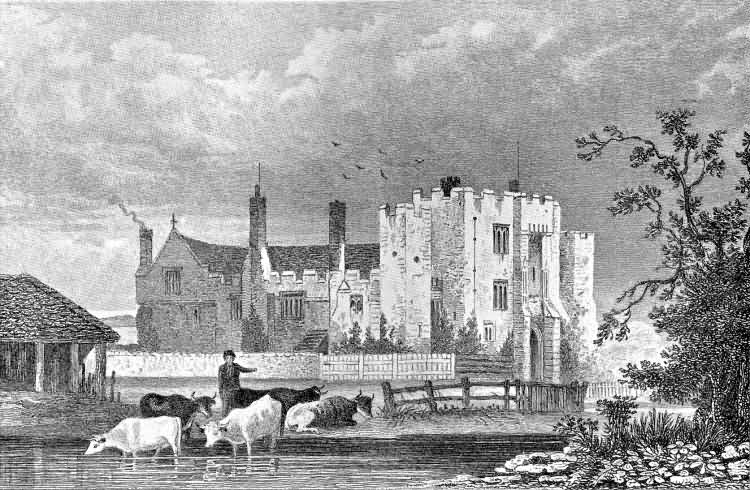

What is clear from Hever’s archives, though, is that for much of its post-Boleyn existence, Hever is to let or is let out. So we have the Waldegraves, who own Hever for 150 years, but barely ever lived there; the same could be said for the Humphreys family; for the Waldos and subsequently for the Meade-Waldos. We have huge periods of time where the Castle isn’t being occupied by people who would make significant changes to the fabric of the property.

This is one of the key reasons that we have so much of the Boleyn’s original house intact for visitors to see today. Tenants would rarely have the means or the motivation to refurbish a property that wasn’t theirs. It seems that for a comparatively large chunk of this time, Hever was rented out in portions to tenant farmers. Life was hard for these farmers; there are many instances of bad harvests and relative hardship.

What is more, we do actually have a murder during this period!

Sarah:

Ooh, do you?

Owen:

We do, yes, it was quite unexpected. One of the tenant farmers met a very grizzley end in 1808. His name was John Humphrey junior. His father had previously held the tenancy and he was married to a woman called Mary. We have some rather dramatic reporting in local newspapers up and down the country; for example, it made the news in Bury St Edmunds and in Hereford.

Sarah:

Good gracious!

Owen:

I know! So the former reports on 8 June 1808 that “Mr Humphrey of Hever Castle, near Edenbridge in Kent, was shot on a footpad [that’s like a sort of walking road] on his way from Westerham market. He’s since died. The coroner’s jury has pronounced the verdict of wilful murder by persons unknown.” Now, it’s believed that the inquest actually was taking place in what is now called the Council Chamber at Hever, but what is unclear from the records is whether anyone was actually arrested, let alone brought to justice for the murder.

Suspiciously, his wife remarried the next year to a local farmer, who then took on the tenancy between 1809-1818. Now interestingly, we do have a letter in the Hever archives dating much later, from 1898. It comes from someone who is trying to find out about the case. It suggests that the new husband, “Knew more of the matter than he ought.” So, this is the man who marries John Humphrey’s wife. It goes on to detail that the murdered John Humphrey haunts his wife and Henry at Hever to the extent that the Castle had to be exorcised by all the neighbouring clergy with the aid of water from the Red Sea and wax candles!

Sarah:

Oh, my word!

Owen:

So perhaps when our visitors report to us that they’ve felt a chill and they might have felt Anne Boleyn brushing against them – it’s not, it’s John Humphrey our former murdered farmer!

Sarah:

So are we surmising there that he was bumped off by a potential love rival, maybe?

Owen:

That’s certainly what the letter is suggesting. It’s really frustrating; I only happened across this murder just before lockdown started so I haven’t been able to get into the archives; I’ve been relying on online information about it. So I’m really hoping we’ve got some coroner’s notes and even some more local newspaper reporting. But yes, one of the theories that are posited, a bit later in 1898, is that a local farmer has bumped him off, married his wife and gained a very nice tenancy at Hever castle.

Sarah:

Not beyond the realms of possibility then!

The Victorians and Beyond…

Sarah:

Not beyond the realms of possibility then! So, the castle is rented by tenants, by farming people, but then there is a turn in the castle’s history and we get the Astor family coming in; the very, very wealthy Astor family who really restore the castle. I’d just love to know more about that – about the castle they bought, and how much restoration did they actually do? What changed and what is left of the Tudor Hever Castle?

Owen:

That’s a really good question! You’re completely right; in 1903, William Waldorf Astor purchased the castle and he throws an absolute fortune into restoring the building – adding on the hundred room extension that looks like a Tudor village behind the castle, and which is now our bed and breakfast called, ‘The Astor Wing’. He also landscapes the grounds to the standard that you see today. That was a huge undertaking; it cost an absolute fortune

Now, Astor liked to propagate the notion that Hever was in a dilapidated state when he purchased the castle, but I simply don’t think that the evidence that we have backs this up. Just before he arrives on the scene, in the 1860’s, there was a group of artists who rented the castle, called The St John’s Wood Clique. I’d highly recommend your readers to check out their artwork; it’s absolutely beautiful and they used Hever as a backdrop to their art.

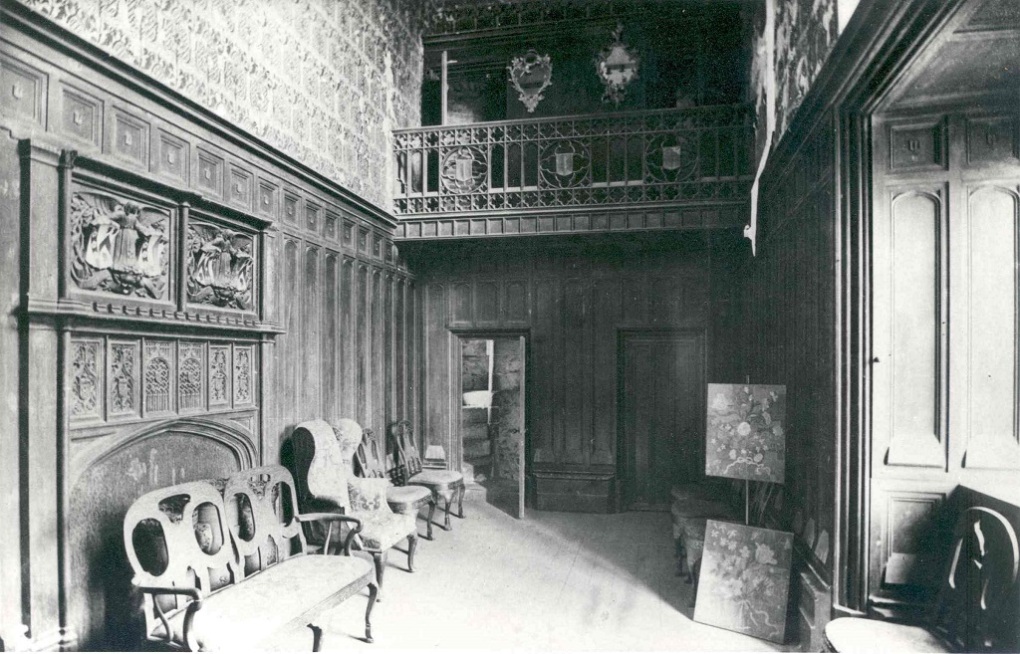

Because of the paintings they paint and the photographs they take, we can glean from this period that Hever is actually in a pretty good state. I particularly recommend a painting of a ghost hunt in Anne Boleyn’s bedroom, painted by William Frederick Yeames. There’s also a really evocative and famous painting of Anne Boleyn being arrested at Greenwich Palace by David Wilkie Wynfield.

So, we’ve got all of this artwork in which, of course, artistic license has been taken, but still we have a very good idea of the proportions of the rooms and what kind of state they were in at the time. In addition, there are two other periods of restoration before Astor gets to Hever. In the 1830s, the castle underwent extensive renovations; what is now the Council Chamber was elaborately panelled; the floor above was taken out and the balcony inserted to create a new music room for Jane Waldo, who then owned it. Further extensive refurbishments were carried out at the castle at that stage.

Then, Captain Seabright took a lease on the castle from 1895 and carried out many renovations less than 10 years before Astor purchased it. Indeed, we do have before and after photographs of the castle during this period. It’s quite clear that Seabright’s renovations have maintained Hever to a very high standard. Moreover, he actually removes many of the overtly Victorian additions to the castle that Jane Waldo had installed.

Now, that is not to say that all his renovations were welcomed at the time or, frankly, remembered fondly today. For example, the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) wrote to The Times in 1899 that their offer of assisting Seabright’s renovations had been declined and Thackeray Turner, the society secretary, showed particular concern about the maintenance of the ancient Tudor guardhouse. This was the castle’s first line of defence; it was situated to the southwest of the castle. Sadly, his concerns proved to be astute, for Seabright dismantled this original, medieval or Tudor feature in that same year, which is a massive loss to the estate.

Sarah:

Can I ask you a bit more about that? Was it like a gatehouse and where would it be, would it be on the other side of the moat?

Owen:

Absolutely. If you can think where the information desk is now, it was most likely located there, just before the outer moat. We do have it in painting, so know what it looked like. It’s where the guard would have been located as part of the first line of the castle defences. Another massive loss is the Tudor stables. These were located in front of the castle, just outside the outer moat.

This was a double-storey complex with vast stables below; it had a staircase up to the second floor with a beautiful open gallery that led to five bed chambers and a 30-foot vaulted chamber, where the grooms and their families lived. It’s just such a tragedy that this beautiful structure was demolished so late in the day. Again, we do have numerous artworks which show us what the exterior looked like. It was just a stunning structure and, much to my amazement, I happened across a beautiful sketch of the interior of the barn just last month.

Sarah:

Oh my goodness!

Owen:

It magically appeared before my eyes when I was reading an article about Kentish barns and includes all the measurements and the structure too. You know, I just love research data like that.

Sarah:

Oh, what a total gem! I know from my ‘In The Footsteps’ research that when you come across something like that, it’s like all your Christmases have come at once!

Owen:

Yes, it really is! Having scolded Seabright for dismantling some key parts of the Tudor estate, it must be said that his efforts, alongside Jane Waldo before him and Astor afterwards, really have helped keep Hever in the amazing condition you see it today.

One thing visitors don’t always appreciate, because of the panelling and maybe the presentation of some of the furniture in the rooms, is that when you visit Hever, you really are walking in the original Tudor house; it’s still here, it’s in situ! You know, if you took all that panelling out, which is essentially just aesthetic, Anne would very much recognise her house. It’s quite extraordinary!

Sarah:

Yes, it’s one of those little quirks of fate that just saves and preserves. I always think the same at Hampton Court, where it was the outbreak of smallpox and the death of the Queen that saved the remaining half of the Tudor palace, so we can still enjoy it today. So thank goodness for those little things! But I agree with you, I know that some people are disappointed when they find out the interiors of Hever aren’t authentically Tudor, but I’m with you, Owen, I think it’s amazing that essentially we still have the same building. Yes, a few of the rooms have been changed in terms of their function, but the house is still there and I think that’s incredible.

Owen:

Yes, I do think it’s right to recognise the scope of Hever’s history; it had a history before it was owned by the Boleyns and it had a long history thereafter. However, if you are interested in Tudor history, you can feel assured that you are walking in Anne’s footsteps when you visit; there’s nowhere quite Hever. There’s nowhere that can claim to be Anne’s childhood home. So, you know, when this awful lockdown abates and we return to a semblance of normality, I would strongly urge people to come to Hever. We’re not a charity, we don’t receive public funds so I’m sure they will very much appreciate support in the near future.

Sarah:

Don’t you worry, Owen, we’ll all be stampeding there the moment we’re allowed! I’ve no doubt about that!

Owen:

Fabulous!

Sarah:

I just wanted to thank you for giving us that wonderful potted history of Tudor Hever right through to today. Thank you so much for sharing all the research that you’re doing. Any idea when we can look forward to that book?

Owen:

Yes, we’re hoping it will be out sometime next year. It’s going to be called ‘Hever: a Castle and its People’ and it’s very much looking at Hever from the point of view of the castle’s social history, examining the impact that people had on the building itself.

Sarah:

Wonderful! Well, we’ll look forward to that and I think all that remains for me is to say thank you so much and I look forward to catching up with you again soon.

Owen:

Thank you so much for having me.

If you’d like to read more about the layout and use of the rooms during the Tudor period, check out my blog on Hever Castle: In Search of the Boleyns.

About Owen…

Dr Owen Emmerson is a social and cultural historian who completed his PhD at the University of Sussex. His doctoral thesis focused on the history of corporal punishment and he has a passion for Early Modern History. As a fan of all things Anne Boleyn, he is currently working as Castle Supervisor at Hever Castle, Anne’s childhood home in Kent. He is currently co-authoring a history of Hever Castle with the historian Claire Ridgway. It will be published as “Hever: A Castle and its People.”

Dr Owen Emmerson is a social and cultural historian who completed his PhD at the University of Sussex. His doctoral thesis focused on the history of corporal punishment and he has a passion for Early Modern History. As a fan of all things Anne Boleyn, he is currently working as Castle Supervisor at Hever Castle, Anne’s childhood home in Kent. He is currently co-authoring a history of Hever Castle with the historian Claire Ridgway. It will be published as “Hever: A Castle and its People.”

wonderful history but you did”not answer my question where were the stables in henrys time?

Hi Sidney, They were directly in front of the main entrance to the castle but set back a little.

Dear Dr Owen, my Father was evacuated to Hever Castle in c1941 and was housed in the stables.

Do you have any history of this time?

His uncle worked for the Times.

thanks

Clare Bingham

Hi Clare, How wonderful. Does your father have memories of the stables and what they were like?