1502 Progress: Beverston Castle, Gloucestershire

Item the xxvij th day of Septembre to Robert Alyn for his costes preparyng logging for the queen…from Walston to Berkeley ij dayes from Berkeley to Beverstone twoo dayes…

The Queen’s Chamber Books

Beverston and the 1502 Progress:

Key Facts

– Henry VII and Elizabeth of York visited Beverston Castle in September of their 1502 progress.

– A single entry in the Queen’s Chamber Books is the only evidence of the visit.

– During the medieval period, Beverston was a small but strategically important castle because of its position close to Bristol to Oxford Road.

– Beverston Castle was a luxurious fortified manor house first developed in the thirteenth century and augmented by Thomas, Lord Berkeley, in the fourteenth century.

– The castle fell into disrepair at the beginning of the eighteenth century when the medieval range was finally abandoned.

The Enigmatic Beverston Castle…

If it were not for a single entry in the Queen’s Chamber Books, dated 27 September 1502, when payment was made to Robert Alyn for preparing lodgings for the Queen (see the quote above), we would be none the wiser about the royal visit to Beverston Castle. This would undoubtedly be our loss, as this lovely location has virtually disappeared from our awareness as a place of significance for those following the Tudor trail.

The main reason for this paucity of information is probably that the visit was fleeting. After five days resting at Berkeley Castle, the royal entourage was on the move and pressing on to reach the next notable destination on the geists: Fairford, where they were to be guests of the wealthy wool merchant Sir Edmund Tame. In a subsequent post, we will hear more about the Tame family and this fascinating location.

However, even this transitory stay gives us ample excuse to bring Beverston back into the spotlight and discover its unassuming charms.

Image: Author’s Own

Lying a couple of miles west of the well-heeled Cotswold town of Tetbury, during the medieval period, Beverston was one of a small handful of minor castles in Gloucestershire, the county being dominated by two defensive behemoths at Berkeley and the county town of Gloucester. However, it was strategically important because of the castle’s position close to the Bristol to Oxford road. This also made it a convenient stopping-off point for important travellers like Henry and Elizabeth.

From Berkeley, Beverston was a day’s ride eastwards for the couple, through the heart of the Cotswolds and an area that, within 30 or so years, would become a hotbed for the Reformation in England; let us remember that William Tyndale was born near the local town of Dursley around 1494.

It was early September as Elizabeth and Henry approached Beverston. Summer was drawing to a close, the golden fields harvested, as August’s long, languid days began to give way to the encroaching chill of autumn’s embrace. As the King and Queen approached the castle, we can imagine the scuffing of horses’ hooves as they crossed the lowered wooden drawbridge traversing the moat. The bulk of the castle’s barbican and gatehouse briefly plunge the glittering spectacle of the royal entourage into shadow before the King and Queen re-emerge into the castle’s bijoux inner courtyard.

The owner at the time of the visit was Sir Edward Berkeley. Edward was born in Beverston in 1428. He spent some time living in Bistherne but eventually returned, becoming the sheriff of Gloucestershire in 1493. By this time, he lived in Beverston and remained there until his death on 4 February 1506. Thus, perhaps Edward was there to greet the royal couple as they arrived at the castle and usher them towards their private apartments.

If you visit today, you will see that the moat on the eastern side of the castle has entirely disappeared, enduring only to the west and south. Thankfully, part of the barbican and gatehouse still stands. At the same time, the footprint of the inner courtyard remains virtually unchanged, helping us follow in Elizabeth’s footsteps in the haven of our imagination.

The Appearance and Development of Beverston Castle

Modern architectural historians classify Beverston Castle as more like a fortified manor house rather than a truly defensive castle. Although it certainly had castle-like features, such as towers, a moat, a drawbridge, and a portcullis, Beverston was built on flat land on the edge of the 7000-acre Berkeley estate and could not be easily defended against attack.

While nothing of note was recorded as occurring during our 1502 visit, Beverston certainly witnessed its fair share of drama across the centuries from the first Anglo-Saxon iteration of the castle, when Earls Godwin, Swegen and Harold met there to ally themselves with King Edward the Confessor in 1050, but instead, they ended up conspiring against him and being forced to flee into exile. Accordingly, there does seem to have been an Anglo-Saxon/early Norman castle on site, which was substantially replaced in the thirteenth century (circa 1225) by Maurice de Gaunt, a descendant of a minor branch of the Berkeley family.

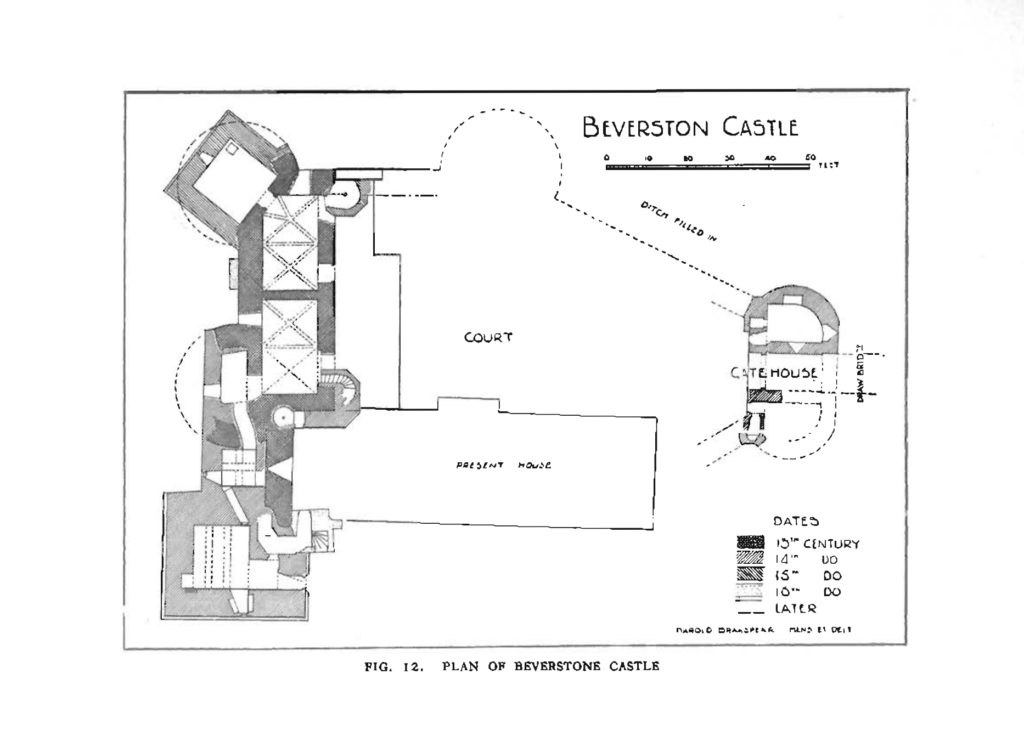

According to architectural historian Anthony Emery, de Gaunt built a luxurious fortified manor house with ranges centred upon a rhomboid-shaped inner courtyard defended by ‘several circular or half-circular towers and gatehouse of ovoid form protected by a drawbridge and a portcullis’.

Image: Author’s Own

The next significant development phase at Beverston came around 100 years later, when Thomas, 3rd Lord Berkeley, acquired the castle. According to Smyth, in his Lives of the Berkeleys, ‘In 22 and 23 years of that kinge (1348-9), hee much re-edified his castle of Beverston where he spent many months in the yeare, especially after it was become the joynture of his second wife and entailed upon her children’.

A later antiquarian, ‘our’ beloved John Leland, passed through Beverston on his rambles through Gloucestershire during the 1530s. He notes that the Beverston we see today was likely built from the spoils of the wars in France, stating that ‘Thomas, Lord Berkeley was taken prisoner in France, but later he recovered his losses by taking French prisoners at the Battle of Poitiers’. The implication is that these were subsequently ransomed, allowing him to ‘build after the castelle of Beverstone thoroughly, a pile at that tyme very pretty.’ However, Emery is suspicious. He feels the more likely explanation is that the wealth was generated locally through good husbandry and the plentiful production of valuable Cotswold wool. (The importance of the wool trade to the region was discussed in much more detail at an earlier location: Northleach).

Lord Berkeley modified the castle by creating a square courtyard surrounded by four ranges. On the east was the principal entrance to the courtyard via the barbican and gatehouse. To the south was once a first-floor hall. This communicated with the Great Chamber in the west range via its high (west end). Sadly, the Great Hall burnt down in the early 1700s, and the site of the hall is now occupied by a two-storey late eighteenth-century range. While not unpleasing in appearance, it stands out like a sore thumb against the adjacent medieval ruins, making the original position of the great hall easy to identify should you visit the location.

Image: Author’s Own

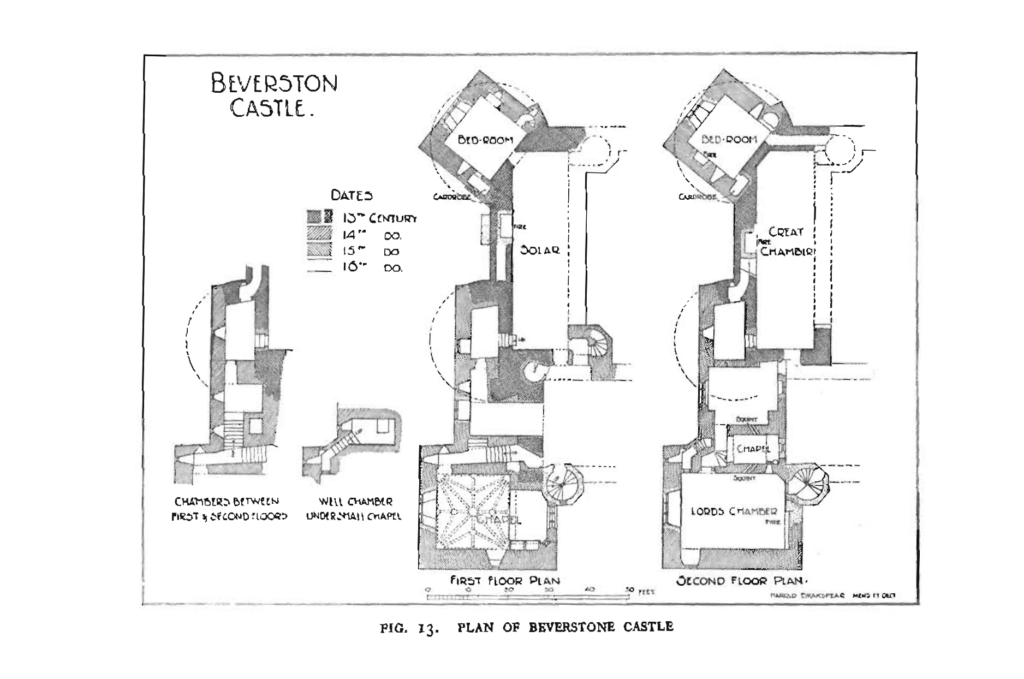

The range to the west of the courtyard is of most interest to us. This housed a three-storeyed living range used by the family and notable guests. Of all the castle remnants that Elizabeth and Henry would have seen, the square ‘Great Tower’ in the southwest corner makes the strongest impression. This entire western range remains intact but is deserted and crumbling. A large central chamber is flanked on either end by two towers, one in the northwest corner and the larger, square tower in the southwest corner (mentioned above). This is sometimes referred to as the ‘Berkeley Tower’. The latter is a veritable rabbit warren of stone staircases, corridors, blocked doorways, rubble and empty rooms.

The beautiful but deserted first-floor chapel within the Great Tower is one of its most notable rooms. Anthony Emery calls it ‘one of the finest of such survivals in any castle’ although it is stripped bare to the stonework. The ceiling of the body of the chapel has a fine tierceron vault with carved bosses at the rib intersections. At the same time, in the east wall, a gaping fourteenth-century window retains just enough surviving tracery to reimagine its former glory. Four gorgeously carved stone sedilia and a piscina are close by, all dating to Berkeley’s refurbishment of the castle in the fifteenth century.

Above the chapel is another large chamber, which Emery calls the Great Chamber, thought to have been reserved for the lord of the manor. This was part of a complex of rooms located at the second-floor level. These included a small adjacent oratory used by the Lord’s priest to conduct the Mass; a squint in its north wall allowed the head of the household to witness the service from the privacy of their chamber; there is also an inner chamber and a couple of smaller spaces, possibly used for storing valuable items.

It is quite probable that Henry himself occupied this chamber as the most important person staying at the castle. However, there is an alternative. On the opposite end of the western range is another smaller tower developed by the aforementioned Thomas Berkeley, who created ‘an independent suite, probably for honoured guests.’

Berkeley replaced the earlier circular tower with a square one, which provided ‘comfortable retiring chambers at first- and second-floor levels with garderobes and a fireplace, linked by a minute newel stair’. In contrast, the chamber on the second floor was heated by an open fireplace. It is extremely likely that either King or Queen – and I guess it would be Elizabeth – occupied this second suite of high-status rooms, second only to those in the Great Tower.

Although parts of Beverston remain occupied as private residences today, the medieval west range was abandoned in the early seventeenth century. I suspect this may have been due to the effects of the English Civil War when Parliamentarians occupied the castle.

As a private residence, you cannot ordinarily visit the castle. However, you can see it from the track adjacent to it and towards the Church of St Mary the Virgin. This takes you directly in front of the original gatehouse/ barbican entrance. You can also stay in one of the converted ancillary buildings where the castle’s north range once stood. The Bothy and The Rooks Apartment are not only lovely places to stay, but you are also allowed access to the castle’s beautifully tended private gardens, where you can get up close to the seventeenth-century south range and the Great Tower.

As for Elizabeth and Henry, their time at Beverston Castle likely spanned one or two nights at most. Their next destination lay across the county border and is another location that is rarely, if ever, mentioned in relation to Tudor history: Cotes Place in Oxfordshire.

THE NEXT STOP ON YOUR PROGRESS IS COTES PLACE.

Places to Visit Nearby

Owlpen Manor (5.5 miles): This Tudor Manor House has a rich history spanning over 1000 years. It is adorned with Arts and Crafts furniture and accompanied by its own resident spirits. It has a very limited public opening—just twice a year!

Dursley and the William Tyndale Monument (10 miles): Positioned prominently on a hill above the village of North Nibley, this monument is dedicated to the martyr William Tyndale. Tyndale’s mission was to translate The Bible into English so that ordinary people could read it for themselves rather than relying on priests for an interpretation. He was later strangled and then burned at the stake.

The monument was completed in 1866 and officially opened on November 6 of that year. After climbing over 100 steps, you can expect a wonderful view of Berkeley Vale and the River Severn to the Black Mountains. The monument is open 24 hours a day, every day. The steps up have automatic lighting.

Berkeley Castle (13 miles): One of very few inhabited and fully intact castles in the country, Berkeley Castle remains largely untouched since it was built in stone during the eleventh, twelfth, and fourteenth centuries. It retains most of its original features, including doors, arrow slits, windows, and even iron catches. Berkeley Castle remains the ancestral home of the Berkeley family and is still privately owned. You can listen to my on-location podcast episode from Berkeley here.

Church of St John the Baptist, Cirencester (14 miles): The Cotswolds is home to some incredible historic churches. An area made rich by its wool trade in medieval times, wool merchants often funded the construction and renovation of churches, which became known as “wool churches.” In this podcast episode, I tour St. John the Baptist in Cirencester and St Mary’s Church in Fairford, two of the most prominent of these wool churches.

Thornbury Castle (18 miles): Once home to Jasper Tudor and later visited by Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn during the 1535 progress, Thornbury Castle was passed to Edward VI and Queen Mary Tudor following Henry VIII’s death. Today, under the attentive stewardship of its current custodians, Thornbury Castle is a luxury hotel and stands resplendent, meticulously restored to echo the majestic splendour of its royal heritage.

Acton Court (18 miles): Visited by Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn on the 1535 summer progress, the owner of Acton Court, Nicholas Poyntz, built a magnificent new east wing onto the existing moated manor house to impress his royal guests. Today, the East Wing, built in just nine months, comprises most of what remains at Acton Court – a rare example of sixteenth-century royal state apartments, including Renaissance-style wall paintings that are said to be the finest of their kind in England. Currently, opening is limited to a couple of weeks in July each year.

Sources

Emery, Anthony, 2006, Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales Vol. 3 Southern England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) p. 67-70

Grose, Francis, 1787, Antiquities of England and Wales (London) Vol. 8 p. 73-4

The Berkeley manuscripts. The lives of the Berkeleys, lords of the honour, castle and manor of Berkeley, in the county of Gloucester, from 1066 to 1618; by Smyth, John, 1567-1640

The Gatehouse Gazetteer: Beverston Castle

Walker, D., 1991, ‘Gloucestershire Castles’ Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society Vol. 109 p. 5-23

Thompson, Hamilton, 1930, The Archaeological Journal Vol. 87 p. 453-5

1928, ‘Proceedings at the Annual Summer Meeting at Stroud, 3-5 July 1928’ Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society Vol. 50 p. 34-6.Bazeley, 1899, ‘Transactions in the Nailsworth District, May 24th, 1899’ Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society Vol. 22 p. 5-9

One Comment