Tudor Day Trips From London: Cambridge

Essential Travel Information:

- By Car: around 1 h 30 mins from central London. Car parking in multi-storey car park: The Grand Arcade Car Park plus 5 min walk to King’s College.

- By Train: From London Liverpool Street, London Kings Cross or London St Pancras to Cambridge (not Cambridge North). At least 4-5 trains an hour.

Price by Train: Train tickets typically start at around £29-45, depending on the ticket type (2023).

Journey Time: 50 mins – 1h 10 mins – 2 h (direct)

Distance from Station to City Centre: 30 min walk.

Key Tudor Locations:

Other things to enjoy:

- Hire a punt

- Walk along the backs

- Hire a student or alumni-led tour

Some Relevant Tudor History

Cambridge has been a leading European university city since its foundation in 1209 when scholars from Oxford migrated to Cambridge to escape Oxford’s riots of “town and gown” (townspeople versus scholars). It flourished as a centre of learning through the medieval and Tudor periods (when most of the colleges were founded or completed), some of them by behemoths of the Tudor age, including Henry VII, Margaret Beaufort and Henry VIII.

Of course, Cambridge remains a first-class university, and needless to say, most of its history and historic buildings are wrapped around its colleges, located in the heart of the old town. This means that the places we touch on here are within easy walking distance of one another.

We will start with listing the dates of visits made to the city by Tudor royalty and the places they are associated with. This is followed by an excerpt from my write-up of Henry VII’s 1486 progress when the King briefly visited Cambridge on his way to Lincoln. Finally, we will summarise where to go and what to look out for when visiting the city today.

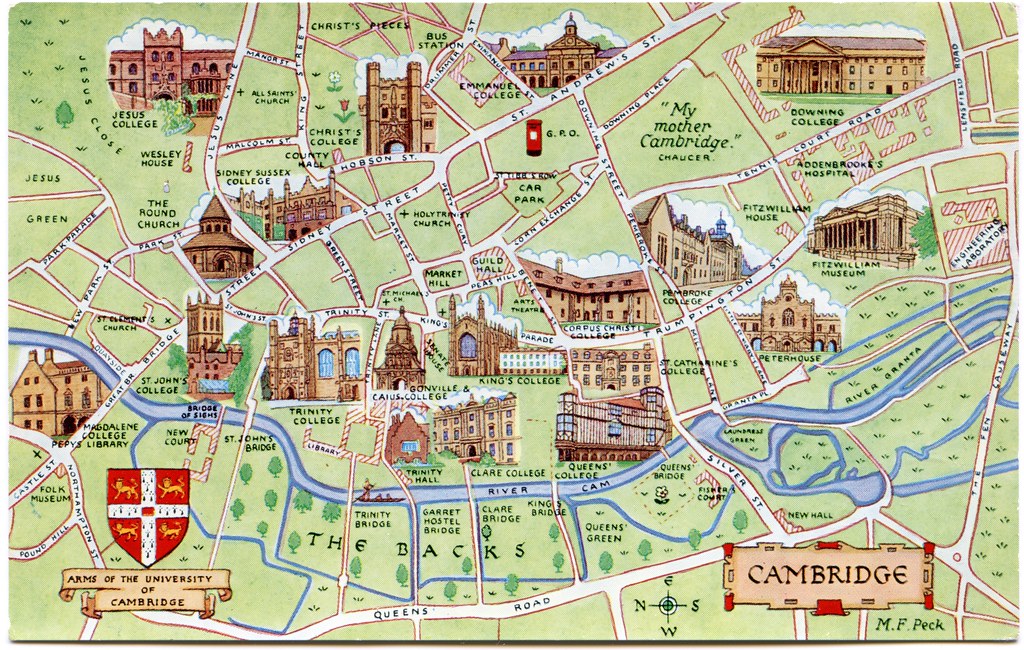

Map of medieval Cambridge; Bridge of Sighs, Cambridge.

Royal Visits to Cambridge 1486- 1564

- Margaret Beaufort: Margaret had a very close association with Cambridge from well before her son became King. It may very well have been on her encouragement that Henry also paid Cambridge a good deal of attention. Margaret was one of the most wealthy women in medieval England, and she used her wealth and influence as ‘The King’s Mother’ to support various educational, charitable and religious projects. It was her confessor, John Fisher (who would later stand in such ardent opposition to Henry VIII’s annulment of his marriage to Katherine of Aragon), who drew Margaret to Cambridge University. She was the principal patron contributing to rebuilding the University Church (Great St. Mary’s). In 1505, she re-founded Godshouse as Christ’s College, fulfilling the promise of her brother-in-law, Henry VI. Margaret was also responsible for founding St. John’s College, which was completed after her death.

- Henry VII visited Cambridge on five occasions: March 1486; 18-20 April 1487; 1-2 September 1498; 22-27 April 1506; and finally, 25-31 July 1507. To learn more about Henry’s first and penultimate visits to the city and his involvement with the building of King’s College, read my account below.

- Katherine of Aragon stayed at Queens’ College on her way to the shrine at Walsingham in 1521. Her stop in Cambridge must have been a deliberate deviation as it lay slightly north of the main route from London via Waltham Abbey and Newmarket.

- Henry VIII stayed at Hitchen Hall in Cambridge on 16-17 October 1522, also on his way to Walsingham. Henry never forgave the scholars at Cambridge (led by John Fisher) for opposing the annulment of his marriage to Katherine of Aragon. In 1546, he closed two colleges and founded his own: Trinity College. The King aimed to found a college that could produce clerics who could be advocates of the reformed faith. The new college was one of, if not THE, richest in Cambridge, as it was funded by the spoils of the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

- Elizabeth I came only once to Cambridge, towards the beginning of her reign in August 1564. She was lodged in the Provost’s House at King’s College and visited most of the colleges in the city. However, the locations most associated with her during the visit were King’s College and its Chapel, which she was very taken by (unsurprisingly!) and the Great St Mary’s Church. This is a good overview of Elizabeth’s stay in Cambridge by The Cambridge Historian.

Henry VII and the 1486 Progress: An Extract

‘[The king] rode to Waltham; and from thens the High Way to Cambrige…where he was ‘honourably received both of the university and the town’.

The Herald’s Memoir

As we saw in the previous entry, the only record of Henry VII’s visit to Cambridge comes from the Herald’s account in which he writes that ‘[The king] rode to Waltham; and from thens the High Way to Cambrige…where he was ‘honourably received both of the university and the town’.

No other detail of the visit is recorded. Emma Cavell’s thesis on the 1486 progress notes that ‘bread, beer and other victuals’ provided during the King’s stay are noted in Cambridge University’s Grace Book Alpha, while payments were also made to the town’s treasurers Robert Ratheby and Richard Holmes for ‘a present given to the Lord, the king’, (Annals of Cambridge, Vol 1 p.232).

These payments confirm the Herald’s account that Henry came to Cambridge. According to Cavell, he arrived around Thursday, 16 March, although the Annals of Cambridge give this date as 12 March. While the location of Henry’s lodgings remains unspecified for this progress, as we shall see, we can gain insight into what likely transpired during this progress by looking at a later visit that Henry made to the town some 20 years later.

However, while the location of the king’s lodgings remains elusive for this section of the progress, we can postulate with a degree of confidence why the king chose to make a short diversion from the main road (Ermine Street) into Cambridge and guess a likely contender for the accommodation of the royal visitor.

As I have already mentioned, Henry was meticulous in reinforcing his image as rightful King of England through word and deed. Since Edward IV had marched through Cambridge just ten days after his accession on his way to Pontefract, the Yorkist king and his successor, Richard III, had visited Cambridge five times in all, with the last visit by Richard coming just the year before he lost his life at the Battle of Bosworth. On this count alone, Cambridge had made itself worthy of Henry’s patronage. However, his Lancastrian inheritance provided another possible motivation …

One of the notable themes of the new King’s early reign is the reverential respect paid to Henry’s late half-uncle, Henry VI: England’s previous Lancastrian King. While many of his contemporaries saw Henry VI as a weak and inept ruler, he was undoubtedly pious, and the cult of Henry VI, (including, eventually, a move to have him canonised) became well-established under Henry VII. This was Tudor propaganda in overdrive and is accepted as part of Henry VII’s attempts to establish the Crown’s legitimacy under the new Tudor dynasty.

One of the notable achievements of Henry VI had been to found King’s College in Cambridge. The late King had been heavily involved in the plans drawn up for the building of this new educational establishment. Unfortunately, due to the onset of the Wars of the Roses in the mid-fifteenth century, Henry VI had run out of money, and construction halted.

Retrospectively, we now appreciate that it was the founder of the Tudor dynasty whose patronage moved the project toward completion, although admittedly, serious progress was not made until 1508, towards the end of Henry VII’s reign, when the outer shell was finally completed. Was this notoriously parsimonious king enthusiastic in intent but not so keen to splash the cash until his coffers were overflowing? It is difficult to say, but it would be Henry’s successor, the eighth King Henry, who would oversee the completion of the project by finishing its interiors, with its piece de resistance, King’s College Chapel, being completed in 1515. If you visit today, you will see it resplendent with Tudor iconography, including the arms of Henry VII as well as the heavy oak coffer which carried the funds provided by Henry VII to continue the work on the chapel.

Yet this may not have been the only influencing factor in Henry’s visit to the town. His mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, had long been a patron of the university with established contacts there. It is not hard to imagine her encouraging her son to make time to visit the town. In fact, the two of them would visit together on at least two future occasions, one of these being in April 1506.

Unlike during Henry’s first visit, the King’s reception of 1506 is recorded in significantly greater detail. There is no reason to suspect that the monarch’s reception 20 years earlier differed significantly since it aligns well with other recorded royal visits to notable towns and cities.

In this account, we hear that the mayor and his brethren rode three miles out of the town, no doubt to meet the king at the limits of the city boundary. The sheriff of the shire was also present. Reforming the procession, the King approached the city. Just a quarter a mile outside of the university, the ‘freres’ (friars) waited to greet their monarch, along with the ‘graduates, after their degrees and all in their habits’. Still on horseback, Henry kissed the crosses belonging to each of the four religious houses before eventually dismounting and kneeling upon a cushion ‘as accustomed’ (BTW This indicates just how this was indeed part of the usual ritual of royal receptions at the time. This certainly persisted at least into the reign of Henry VIII, where we see the exact same customs being played out, for example, during the king’s visit to Canterbury in 1520 and Gloucester in 1535).

By that time, John Fisher, whose life would come to dominate court affairs during the King’s Great Matter of the 1530s, was Chancellor of the University (as well as personal confessor to Margaret Beaufort). He performed a religious ceremony in which he ‘senys’d’ the King before greeting him, most likely with a Latin oration. Afterwards, Henry remounted his horse and made his way through the town, by Blackfriars, before heading to his lodging at Queens’ College.

Now this latter point is interesting. Queens’ was originally founded by Margaret of Anjou, wife and consort of Henry VI (there’s that name again!). After the fall of the House of Lancaster, Elizabeth Woodville refounded the college. (Hence, interestingly, it is called Queens’ College and not Queen’s College). Thus, this college had Lancastrian, as well as Yorkist connections, was well-established by 1486 and has what I call ‘form’, i.e. it was deemed suitable to host one of Henry’s subsequent visits. Given these facts, I do wonder whether Queens’ was where Henry VII lodged on this first progress. I daresay we will never know for sure, but it is a tantalising possibility.

The 1506 account states that Henry rested for an hour in his lodgings at the college. However, since it was Garter Day – 22 April – there was no time for idle pleasure. The King soon donned his Garter Robes and, accompanied by other Knights of the Garter, went to King’s College Chapel. This was likely just a short processional walk from the King’s lodgings in Queens’ College; early maps of Cambridge show the chapel lying directly opposite the latter college. There, John Fisher led the ‘Divine service both the Even, the Day, both at Matins etc and the Service of Requiem on the morrow’.

Of course, as I have just mentioned, the chapel was incomplete at the time, and according to King’s College website, the service was ‘held in the first five bays of the Chapel, which had a timber roof but no stone ceiling vaults. The open end was boarded up and decorated with the coats of arms of the Knights of the Garter painted on paper’.

The only other fragment of information we have of the 1486 progress comes once again from the accounts recorded in Cambridge University’s Grace Book A, when in the same breath as talking about the location of bread and other victuals for the King, it also refers to the acquisition of rolls and wax (‘scriptura rotularum et cera’). Presumably, some business was being transacted, and the King wished there to be a record of it.

From Cambridge, Henry likely headed in a north-westerly direction, towards the Great North Road, travelling via Huntingdon and Stamford towards the first major destination on the progress. The ancient city of Lincoln, standing proud atop a lofty plateau, awaited England’s new monarch.

Visiting Today

King’s College & King’s College Chapel

As you have read above, King’s was founded by the pious King Henry VI in July 1446, but completed first through the attention and funding provided by Henry VII and then finally by his son, Henry VIII.

The chapel was completed in 1515 when the body of the church was finished; Henry VIII used the £5000 in his father’s will to complete the vaulting, the glazed windows, the screen and much of the Chapel’s woodwork. Thus, we see a building constructed in the high Gothic style with many decorative features dating from the Tudor age. The chapel is covered in Tudor iconography, both inside and out. It is breathtaking!

Outside of April – June, you can visit the chapel and grounds, and once you have your ticket, you can linger and enjoy the grounds for as long as you wish. April – June marks the ‘quiet’ season when exams are taking place, so only the chapel is accessible during these months.

King’s College Great Court. Mark Williamson, CC BY-SA 4.0,via Wikimedia Commons.

Finally, King’s is right in the heart of the old city opposite the Great St Mary, so you might want to begin your adventure here.

Features to pay particular attention to:

The fan-vaulted ceiling: The Chapel features the world’s largest fan vault, constructed between 1512 and 1515 by master mason John Wastell.

The windows: There are 12 large windows on each side of the Chapel and two larger windows at the east and west ends. Except for the west window, they are by Flemish hands and date from 1515 to 1531. Barnard Flower, the first non-Englishman appointed the King’s Glazier, completed four windows. Galyon Hone and three partners (two English and one Flemish) are responsible for the east window between 1526 and 1531. The only modern window is at the west end of the church. That dates to the Victorian period.

See if you can spot small panes of glass dotted about the chapel that are at eye level and which show the initial ‘HE’ (Henry VII and Elizabeth of York) and ‘HR’ (usually Henry VIII) or the pomegranates of Aragon, Katherine’s emblem. If you look VERY carefully, high up, sited centrally on the east window, are the initials ‘H’ and “K’ for Henry VIII and Katherine Howard. So, three Tudor queen consorts are recognised in the same space – unusual. A pair of binoculars might be useful!

The Rood Screen: Henry VIII erected this sizeable wooden screen that separates the ante-chapel from the choir and supports the organ in 1532–36 to celebrate his marriage to Anne Boleyn. The screen exemplifies early Renaissance architecture, strikingly contrasting to the Perpendicular Gothic Chapel. The much-quoted Sir Nikolaus Pevsner said it is “the most exquisite piece of Italian decoration surviving in England’.

The Hacomblen Lectern: In the centre of the choir is a fabulous lectern, which dates from the Tudor period. Robert Hacomblen had it made and gave it as a gift to King’s College. He was Provost from 1509 to 1528 while the Chapel was being finished, meaning he oversaw the installation of the fantastic stained glass windows and the graceful fan-vaulted ceiling.

The Great Trunk: In the exhibition housed in the side chapel (enter via the choir) is a large trunk or chest. It would be easy to miss! However, this was the trunk that Henry VII sent to Cambridge containing £5000 as funds to continue work on the chapel. An enormous sum of money that no doubt arrived as gold sovereigns. Imagine opening the chest and finding that inside!

Visiting: You can visit King’s College Chapel every day of the week for a fee, or you can attend one of the evensong services or the sung Eucharist on Sundays for free. All the visitor info you need can be found here. Do book your timed ticket in advance from the website to avoid disappointment, particularly during high season.

As the Great St Mary is directly across the road from King’s, it makes sense to head there next.

King’s College Chapel, Ardfern, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Great St Mary’s Church

The Great St Mary Church is the University Church of Cambridge. There has likely been a church on the site from the eleventh century, but the current building was constructed between 1478 and 1519, with the tower finished later, in 1608. The construction cost was covered mainly by Richard III, Margaret Beaufort and Henry VII.

As we have seen, Elizabeth I famously visited it and stunned the academic audience with her flawless Latin oration. Famous Reformist clerics, including Erasmus and Martin Bucer, who influenced Thomas Cranmer’s writing of the Book of Common Prayer, preached in the church. The latter was buried there.

Under Queen Mary I, Bucer’s corpse was exhumed and burnt in the marketplace. But after Elizabeth I acceded to the throne, she had none of it and ordered that the dust from the place of burning was replaced in the church. Whatever is left of Bucer now lies under a brass floor plate in the south chancel.

The church is plain and unremarkable in appearance, but its place in Tudor history and its relationship to the visit of Elizabeth I make it worthy of a visit.

Visiting: You can visit the church every day of the week for free. It is also possible to pay to climb the tower and get some great shots of King’s College from the top! Check out the website for all the latest.

Great St Mary’s, Cambridge by Ben Keating, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Queens’ College

Founded first by Margaret of Anjou (1448) and then refounded a decade later by Elizabeth Woodville (1465), hence the name Queens’ and not Queen’s College. The early buildings were centered around two courtyards, the Old Court and Cloister Court. Of course, the College has grown over time and is one of two Cambridge Colleges to have spilt over the River Cam, with the famous Mathematical bridge linking the so-called ‘light’ (new) side and the ‘dark’ (old side), as students at the College refer to them.

John Fisher was President of the College briefly between 1505 and 1508 but resigned to concentrate on his patronage of St John’s and Christ’s College.

Perhaps the most interesting building is the President’s Lodge and the Riverside Building, which partly comprises the only timber-framed construction in any of the university’s colleges.

These two ranges are found in Cloister Court and have been dated to the mid-fifteenth century (between the 1440s and the 1490s). The Riverside Building unsurprisingly fronts onto the River Cam. Adjacent and perpendicular to this is the part timber-framed range, which contains a mid-sixteenth-century-long gallery on the first floor. This is thought to date to after 1537; its construction used material from the neighbouring Carmelite Friary, which was dissolved around this time.

President’s Lodge, Queen’s College, Cambridge.

Visitors said to have stayed at the Lodge include King Henry VII and Elizabeth of York (1497), Lady Margaret Beaufort (1505), Queen Katherine of Aragon (1521), and Cardinal Wolsey (1520). For much more detailed information on this building, click here.

This is another useful, free e-source on the history of Queens’ if you want to read more.

Alumni of Queens’: John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester and John Whitgift, Elizabeth I’s last Archbishop of Canterbury. He attended Elizabeth on her deathbed.

Visiting: The college is open most of the year, except for the examination ‘quiet’ period from mid-April to the end of June and on certain college open days for prospective students, ceremonial days and the Christmas holidays.

The areas you can access are:

- Old Hall and Chapel are generally open but are subject to the College’s events programme.

- All cloister areas and other walkways are open.

Although you can see the Riverside Building and Presidents Lodge from the outside, unfortunately, the interiors are not accessible to the public. For all the information you need to plan your visit to Queens’ click here.

St John’s College

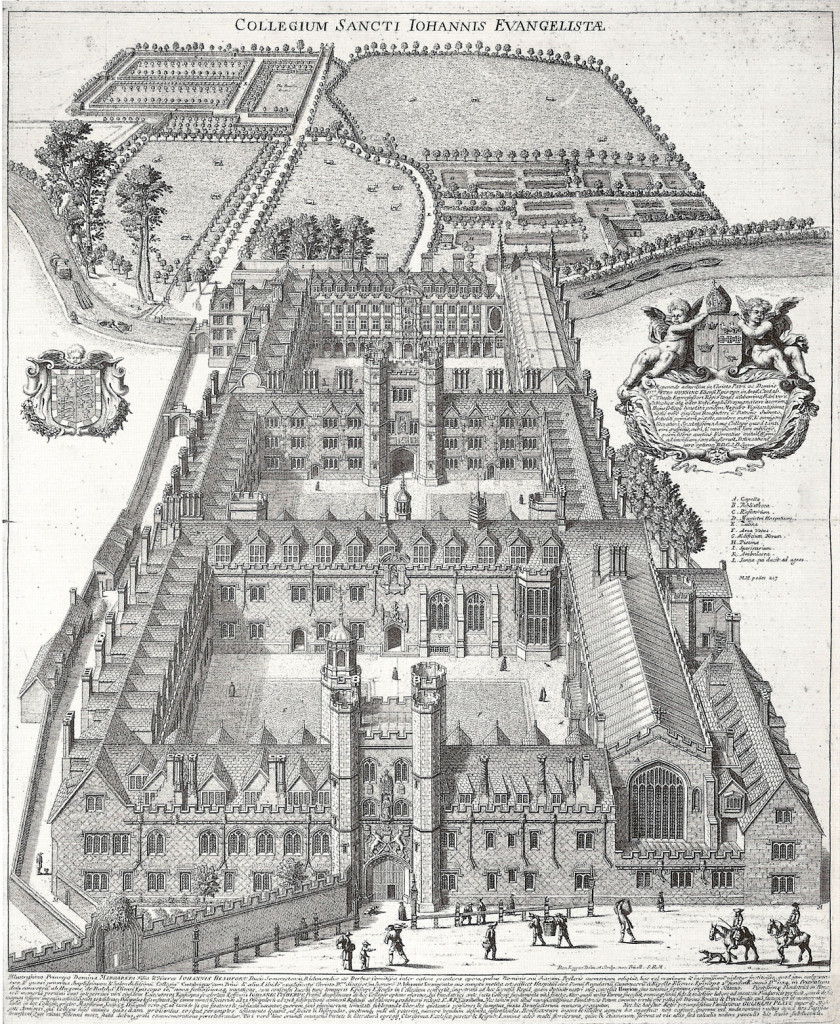

Lady Margaret Beaufort founded the college on the encouragement of her confessor, John Fisher, who incidentally was also made Bishop of Rochester and Chancellor of the University in 1504. The land was reclaimed from a medieval hospital of St John, which had become dilapidated by the late fifteenth/early sixteenth century.

However, the funds from Margaret’s estate were not made available to start the project until a few years after her death in 1509. It was Fisher who guided the building of St John’s College to completion.

St John’s is one of the largest and wealthiest of the Cambridge colleges and, alongside Queens’, is the only college to straddle the River Cam via the famous ’Bridge of Sighs’. It is a vast complex of buildings arranged around 12 courtyards, but from our point of view, the buildings of the most interest are concentrated around the first two.

Heading north from King’s College along Trinity Street, with its quaint shops and boutiques, you will eventually reach the outer gatehouse of St John’s. The architectural form is immediately recognisable as Tudor and is adorned with heraldry associated with its foundress, You can spot her ensigns, the Red Rose of Lancaster and Portcullis prominently displayed. There are also the college arms flanked by heraldic beasts known as yales, mythical creatures with elephants’ tails, antelopes’ bodies, goats’ heads and swivelling horns. The figure above the centre of the gate represents St John.

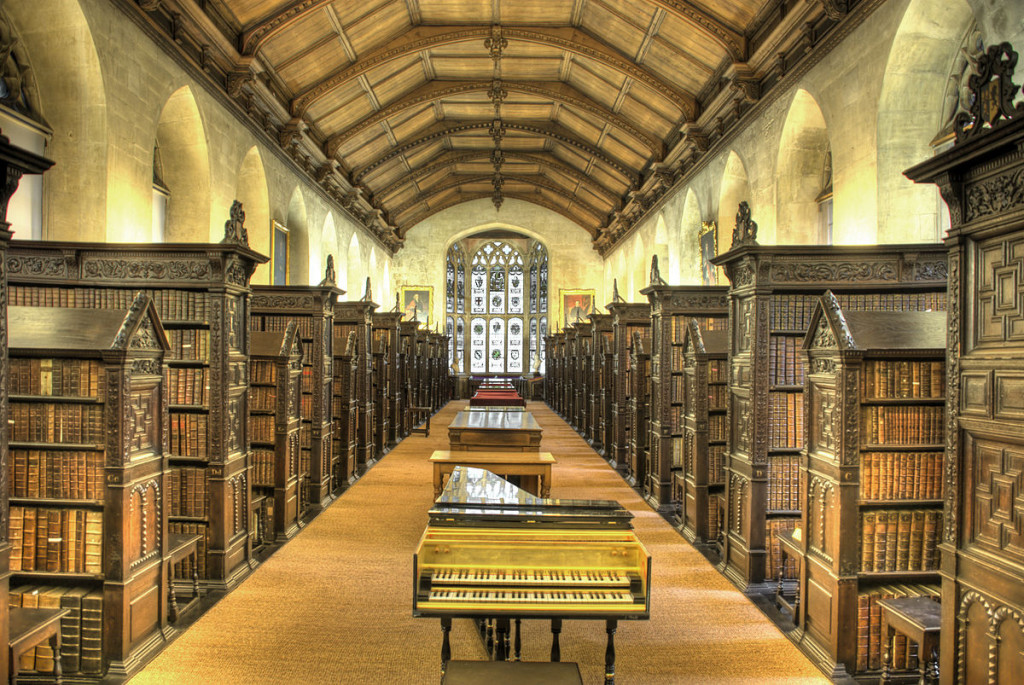

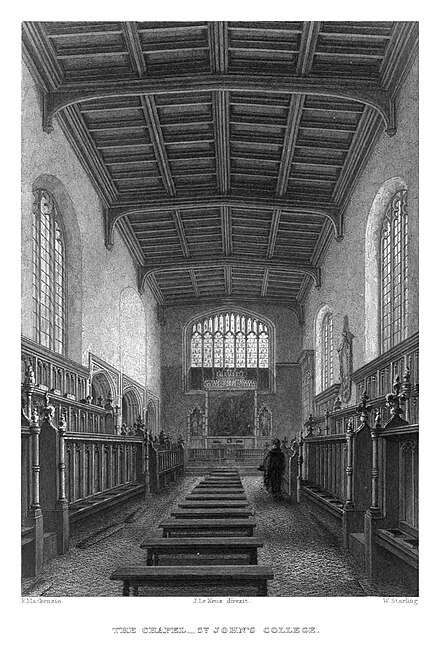

St John’s Old Library; St John’s College; St John’s Hall; St John’s College Chapel.

Inside the gatehouse is the First Courtyard, showing a range of architectural styles. This First Court was constructed with the first building phase between 1511 and 1520. While the gatehouse range is Tudor, much as it would have appeared in the sixteenth century, the south range (to your left as you enter) has had a Georgian facade added to the original Tudor buildings.

However, the most dramatic change is to the north and the college’s chapel. Sadly, the medieval chapel salvaged from the original hospital complex was deemed too small and perhaps not grand enough for the college. So, while some of the interior fittings were saved and later reused, the building was pulled down, and a grand, new (Victorian) chapel was constructed in its place. George Gilbert Scott designed this, perhaps one of the most sought-after architects of the day known for his faux-Gothic style.

So, while the chapel is a beautiful space when you visit, know that this is a much later building and not contemporary to John Fisher’s original college.

In the Second Court, Tudor buildings abound! It was built from 1598 to 1602 and has been described as ‘the finest Tudor court in England’. Built atop the demolished foundations of an earlier, far smaller court, ‘Second Court’ was begun in 1598 to the plans of Ralph Symons of Westminster and Gilbert Wigge of Cambridge. The project to rebuild this part of the college was financed by Mary Talbot, Countess of Shrewsbury (daughter of Bess of Hardwick). To commemorate her patronage, the Shrewsbury Gatehouse, which separates this court from the next, displays her statue and heraldry.

Famous Tudor Alumni: William Cecil, Lord Burghley and John Dee, Elizabeth I’s astronomer.

Notable Tudor Events: Elizabeth I rode into the hall at St John’s during her tour of the city’s colleges in 1564. Sadly, as far as I am aware, it cannot be visited by the public.

Visiting the College: St John’s is one of the most popular colleges to visit as you can wander around the extensive grounds and visit the chapel and the beautiful Bridge of Sighs. There is an entrance fee, but once in, you can explore the courts and grounds at your leisure. Do check out access before your visit, though, as, like many of these colleges, the opening times can change at different times of the year.

Trinity College

Trinity College was founded in 1546, at the end of Henry VIII’s life. It emerged from the merger of two medieval colleges, King’s Hall and Michaelhouse (both initially established in the fourteenth century).

The new college was funded and endowed with proceeds of the Dissolution of the Monasteries and was, and still is, the wealthiest of all the Cambridge Colleges. It is also the largest and boasts many Nobel Prize Winners.

Presumably, because it was founded by the Crown, the Provost’s / President’s Lodging at Trinity also remains the official place of residence of the current monarch when they visit the city.

The college is another of the most popular colleges to visit because of its grand outer courtyard and splendid buildings.

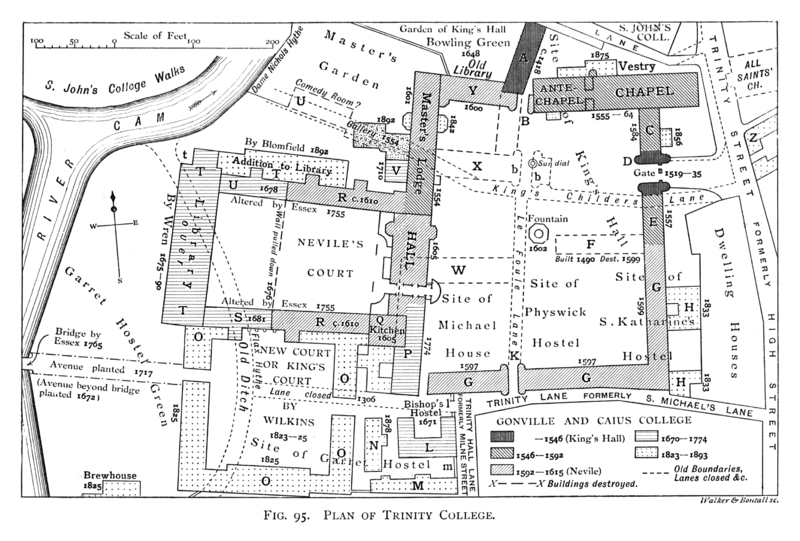

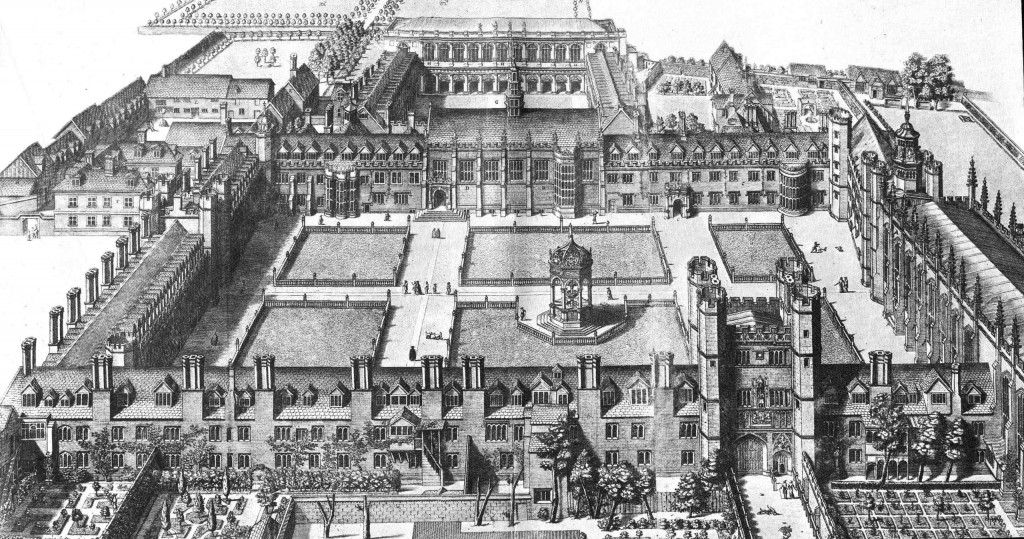

Plan of Trinity College, 1897; Plan of Trinity College, 1690; Trinity Great Court; Trinity Great Court today; Trinity College Chapel.

Sited between King’s College and St John, you can admire the gatehouse from the road. The statue of Henry VIII, as the college’s founder, is immediately recognisable…just take note of what he is holding in his right hand. It should be a sword…but a practical joke played at some point means that the sword is a thing of the past! Of course, the gatehouse is Tudor, as are most buildings surrounding the ‘First’ or ‘Great Court’. This was built principally between 1599 and 1608, and so, in truth, is late Tudor / early Jacobean in design.

The second court, or Nevile’s Court, was built slightly later in 1614 and remodelled in parts over the next two centuries – and thus, you will see the difference in the architecture.

The Chapel, located close to the outer gatehouse, is mid-sixteenth century. Although it appears to be an ornate mid-Tudor building from the outside, inside, it is relatively plain and cannot compare with the beauty of King’s.

Useful Links

For visitor information on the places mentioned in this blog, please use the links below:

Some of the locations in this blog are explored in my book, In The Footsteps Of The Six Wives Of Henry VIII – you can purchase a copy here.