Ockwells Manor and the Legend of the Severed Head

History is full of legends. One such story revolves around the tale of what happened to Sir Henry Norris’ (sometimes called ‘Norreys’) severed head after he was executed on Tower Hill on 17 May 1536. The story goes that his family managed to retrieve it, and while Sir Henry’s body was buried in the grounds of the Tower, close to the Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula, his head was spirited away to the family home of Ockwells Manor in Berkshire, where it was buried beneath the floor of the chapel.

Nearly 500 years after his death, we will travel to Ockwells to recreate the Norris’ sixteenth-century house and to assess the likely truth surrounding the ghoulish folklore of Sir Henry’s head.

Ockwells Manor – The Norris Family Home

Ockwells Manor is a veritable gem of a house constructed during the late medieval period by Henry’s great-grandfather. Incredibly, it survives mainly intact to this day. I am fascinated by these lesser-known Tudor houses. A little like Compton Wynyates (which incidentally was the country seat of the man Sir Henry followed as Henry VIII’s Groom of the Stool, Sir William Compton), Ockwells Manor is a place I have long lusted after seeing. Unfortunately, like Compton Wynyates, Ockwells is in private hands and not open to the public.

Of course, Sir Henry Norris gained notoriety as being one of Anne Boleyn’s alleged paramours, whose life was viciously cut short during that fateful month of May 1536. The story supporting the accusation of treason against Sir Henry was most likely fabricated by his enemies on the back of an ill-advised, throwaway comment made by Anne herself. She publicly accused Henry VIII’s Groom of the Stool of ‘looking for dead man’s shoes’. In doing so, she was unwittingly condemning Norris to death. Most historians now believe the coup which took down the Boleyns, and in which Henry Norris was ferociously swept up, was deliberately orchestrated and based on little more than tittle-tattle, gossip and ruthless factional court politics.

Ockwells Manor is often mentioned in the same breath as Sir Henry and the Norris family. What I long assumed (before writing this article) was that it was Sir Henry’s family home at the time of his downfall. As I have discovered, the facts have become just a little blurred, and we need to be more precise.

What is undeniable, though, is just how beautiful this house is. Ockwells Manor recently went on the market for offers over £10 million. The estate agent’s write-up gives us a rare insight into the interiors of the Norris family home (link at the end of this article).

While it was not the only notable property owned by the family at the turn of the sixteenth century – the other one was Yattendon Castle, also in Berkshire – it is the only one of the two to survive. All that remains of Yattendon are earthworks that indicate the site of the old moat.

However, Ockwells is an entirely different story.

The History of Ockwells Manor

Ockwells Manor was constructed by John Norris, Sir Henry Norris’ great-grandfather, in the 1450s. The renowned architectural historian Anthony Emery states that there is no evidence of an earlier house on the site.

John entered royal service early in his life, climbing the greasy pole until attaining key household positions under the Lancastrian King Henry VI, which included Master of the Royal Wardrobe and Treasurer of the Queen’s Chamber. John Norris would attain his knighthood under the first Yorkist king, Edward IV. However, his second marriage to a Kentish heiress brought even greater affluence to the family, paving the way for the building of Ockwells Manor.

There is no doubt that Ockwells is worthy of Pevsner’s praise as being ‘the most refined and most sophisticated timber-framed mansion in England’. Its construction was heavily influenced by nearby Eton College, only 7 miles away. This building was under construction around the same time as Ockwells, and the latter’s double-storeyed cloister, running around the small inner courtyard and sporting unglazed windows, was copied from there.

The Layout of Ockwells Manor

So, what did the Norris family home look like? Directly in front of the house was a large rectangular area, which tapered towards the entrance to the house. This tapering added drama to the approach toward the family home: a kind of trompe l’oeil. The outer area was initially divided up to form two large courtyards. First came the base court, surrounded by stables, a barn and a dovecote.

Closer to the house was the slightly smaller outer court containing a possible lodging range for guests on the west and ‘additional chambers’ on the east side. A chapel was included in the latter range, sited at the south-east corner of the house. This chapel is said to have been destroyed by fire in 1720. Of course, it is here that rumour has it that Sir Henry Norris’ head was buried. We will come back to that shortly.

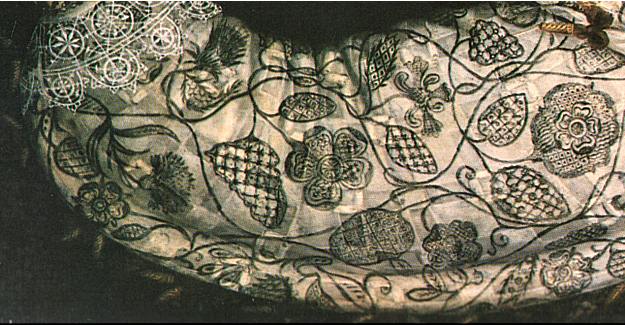

The main house was built around a small, quadrangular inner courtyard. It was timber-framed, built upon a brick footing with brick nogging between the timber frame [Brick nogging = a construction technique in which bricks are used to fill the vacancies in a wooden frame]. The Great Hall occupied the range facing the outer courtyard. It was accessed via an entrance porch at its low end.

The hall had a typical arrangement of a low end separated by a screen’s passage and a high end, lit by large windows, including an elegant oriel window. These windows contain one of the country’s most beautiful surviving displays of original fifteenth-century armorial glass. The coats of arms included are a who’s who of the Lancastrian court: patrons, friends and connections of its builder, Sir John Norris. They include the arms of King Henry VI, Queen Margaret of Anjou, the Duke of Warwick, Duke of Somerset, Duke of Suffolk, Bishop of Salisbury, James Butler, the 1st Earl of Wiltshire.

Entrance via a great hall was not unusual, but the layout of the rest of the house deviates from the norm. Rather than the kitchens being located off the screens passage at the low end of the hall, Sir John inserted a two-storey chamber block to accommodate family and friends. The downstairs probably contained a withdrawing chamber with solar panels on the first floor (second floor if you are used to US nomenclature) forming the main bedchamber.

The kitchens, larder and buttery were at the back of the house, occupying the range opposite the great hall (as seen in the above floor plan). Although the larder and pantry have now been knocked through and converted into a billiard room, the large serving hatch from the buttery still survives, such that it is easy to imagine a flurry of servants collecting wine and flagons of ale to be taken to the great hall.

The kitchen west of the adjoining buttery was initially full height, but a ceiling has since been inserted, creating the first floor, thereby reducing the scale of the original room. It communicated directly with the high end of the hall via a corridor, which has since been enlarged to form a lobby that gives access to a later seventeenth-century staircase leading up to the first floor.

Finally, off the high end of the hall was the principal withdrawing chamber, with the solar above. This was a typical arrangement for a medieval hall house and would have been the most private space in the house, reserved for the family and honoured guests.

But the question remains: Was this Sir Henry Norris’ family home? Well, the answer is ‘yes’ and ‘no’.

Sir Henry Norris at Ockwells

Most commentators agree that Sir Henry was the second son of Sir Edward Norris and Lady Frideswide Lovell. Although probably born at Yattendon, at this point, the Norris family was also in possession of Ockwells Manor. Indeed, Sir Edward died at Ockwells in 1487, aged just 23. In the interim, he had managed to have three children by Frideswide: John, our Henry, and Mary Norris.

It is difficult to say exactly how old were the two brothers at the time of their father’s death. Various sources give widely different dates. Most likely, however, is that Henry was about five years old when his father died. Therefore, we can safely say that he knew Ockwells well, and the youngster must have spent time running around its rooms and corridors with his elder brother, John.

As the eldest son, John was destined to inherit the house at his majority. Frideswide, their mother, was alive until 1507. So, perhaps we may assume that the family split their time between their two principal properties at Ockwells and Yattendon, with their mother acting as chatelaine of the Norris estates on behalf of her son.

However, we know that by 1517, John had become the owner of the manor because, in that same year, there is a record of him forfeiting his land and property in exchange for a pardon, having been found guilty of murdering a certain John Enhold.

At this point, Thomas Fettiplace, the husband of Sir John’s aunt, Elizabeth Norris, was placed as trustee for Sir John’s heirs. Whatever the role of trustee meant, Thomas seems to have become the owner of Ockwells from this point because, after his death in 1523, the property passed through the Fettiplace family.

So, back to Sir Henry’s head! When he was executed in 1536, the Norris family had not owned Ockwells for 19 years. While his relatives were its new ‘guardians’, his wife, Mary, was already dead, and his children were still in their minority.

There were no direct descendants to fight for his head – as Sir Thomas More’s daughter, Margaret, had done when her father was executed in 1535. While it is possible that the Fettiplaces of Ockwells Manor went out on a limb to retrieve poor Sir Henry’s head, my feeling is that it is not so likely and that the story of the severed head under the floor of the family chapel at Ockwells was created to add dramatic intrigue to the already grisly affair.

Ockwells Lives On…

Whether the legend is true or not, Ockwells Manor has survived the test of time. According to Emery, the house is ‘a prime example of a mid-century residence, designed to impress [John] Norris’ courtly friends and to be a convivial centre to entertain them, and an unequivocal statement of his success and affluence.’

Perhaps we might describe Ockwells as Sir Henry Norris’ childhood home, although it was lost to the Norris family in 1517 following a dramatic turn of events. With that, it seems unlikely that the skull of the debonair and widely liked Sir Henry is buried somewhere in its grounds, whose closeness to the king and the Boleyns enmeshed him in the coup of the sixteenth century.

Very interesting article. Would love to know if his head really is buried on the property.

I know…shall we call Time Team!!!

I love to see the beautiful home of my ancestors. The story was nicely written, and intriguing. Thank you for sharing. I have more information to investigate.

Hi Jolene! Thanks for reading and leaving such lovely fedback. Best wishes, Sarah

Sometimes, traitors’ heads were put up in a public place as a warning. However, I have never heard that Henry Norris’s head was displayed in that way. It seems most likely it was buried with the rest of him within or near the Tower of London.

Oddly, he has no descendants sharing his surname.

Such interesting history.I am finding out more and more of my families history, fascinating.

Thank you,

Teresa Lou Norris

Thanks! Glad you enjoyed it!

OCKWELLS MANOR HOUSE, Cox Green

The manor was originally given, in 1283, to Richard le Norreys, the chief cook to Queen Eleanor.[2] It passed down through the Norreys family, ending up in the possession of Sir John Norreys, Keeper of the Wardrobe to Henry VI, who started re-building the manor in 1446.

In the windows of the great hall, Sir John inserted beautiful stained glass, proudly showcasing his Lancastrian connections by displaying the arms of his friends at Court:

The Norreys family lived there until 1517. At that time, Sir John’s great-grandson, also Sir John, had to surrender the estate in return for a pardon after having murdered a certain John Enhold of Nettlebed. Ockwells was then owned by Sir John’s uncle, Sir Thomas Fettiplace. It passed through the Fettiplace family, before being owned by the Day family.

Sir John Norreys is a distant relation to my wife Marjorie (via Robert HIGHAM, her father) and is the Great Grandfather of Sir Henry Norris (Norreys) who was beheaded by King Henry VIII following a suggestion he had an affair with Anne Boleyn and is buried at The Tower of London.

The property was given to Sir Thomas Fettiplace, a distant relative of my Mothers family (on the Orrell line) meaning our families crossed all those centuries ago.

Learning so much about family history (on both mine and Marjorie’s side) and amazing just how much you learn – both families originated in Normandy France and were instrumental with William the Conqueror during the invasion of 1066.

How far back will I be able to investigate ?

Tony Murray CEO

Directors Club

Liverpool

Great history, Tony! Thanks for posting it here. You are so lucky to be able to trace back your family connections like that. Just wonderful!

The Norris family was not Norman but Anglo-Saxon like 99% of England’s people.

Very enjoyable article. I had never heard this tale of HN’s skull before. Thank you.

Glad you enjoyed it. Looks like with your surname you might have some ‘skin in the game’ as they say : )