Woodstock Manor: An Ancient Pleasure Palace and Doleful Prison

Recently, I visited Blenheim Park in North Oxfordshire, the site of the once magnificent Woodstock Manor, the most ancient, royal palace in England. Standing next to a solitary plinth, which is all the remains to mark where this historic palace once stood, I felt a deep sadness. This was not only for its tragic loss at the hands of an overentitled duchess, but I felt that I couldn’t fully visualise how the palace once looked.

I felt disconnected from something I yearned to know more intimately.

Right there, I committed to finding out as much as I could about the palace and to write about it here, on this blog. But for this lover of Tudor history, there was an unexpected revelation in store. During the research, I discovered that I, like many others, had a misconception about Woodstock Manor and its place in history. I just love it when I am surprised by the research! But I am running ahead of myself. To appreciate this location, we need to go back in time…way back…

Note: There is a podcast to accompany this blog. The link is at the end of this feature.

Woodstock Manor: The Stuff of Myth and Legend…

The Tudor dynasty claimed six major royal houses that could accommodate the entire royal court of around 1000 people. Five of these majestic buildings, Whitehall, Richmond, Greenwich, Hampton Court and Eltham Palaces, were arranged in and around London. The sixth was an extraordinary outlier, situated around 65 miles northwest of the capital: Woodstock Manor in North Oxfordshire.

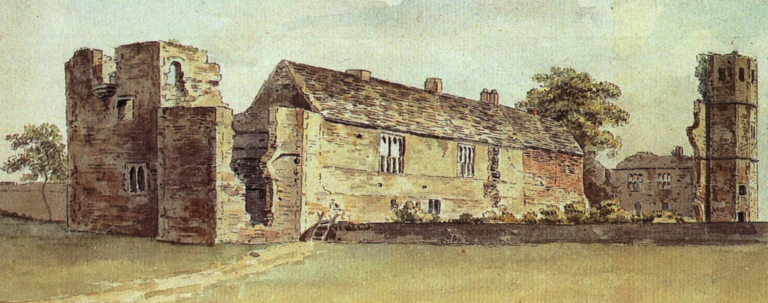

Absolutely nothing remains of this once noble house. It was obliterated by Sarah, 1st Duchess of Malborough, during the building of Blenheim Palace in the eighteenth century. The reason? It ruined her view from her newly built home! Because nothing survives of the palace, I think Woodstock Manor is less often referred to than its other royal ‘cousins’.

Yet, Woodstock Manor was by far the oldest of the royal palaces, constructed by Saxon royalty. Early Norman kings consolidated Woodstock’s position as a major royal residence in the twelfth century. Henry I and then his grandson, Henry II, were responsible for most of its aggrandizement. The latter would inveigle the place with the stuff of myth and legend with the tale of ‘fair Rosamund’. She was the king’s mistress. Henry II lodged her nearby in a place that would become synonymous with her name, which we will hear more of later.

The Norman kings regularly visited Woodstock Manor because of the peerless hunting to be had in the extensive woodland surrounding the palace. The convergence of five forests, including those of Cornbury, Wychwood and Woodstock, resulted in around 500 square miles of prime hunting land. That is enormous!

Most of this forest has since been felled, but a single, surviving oak in Blenheim Park is known to date back to this early period. It is captured in the image above. If only that tree could speak and whisper its stories to us. Can you imagine what it might tell us?

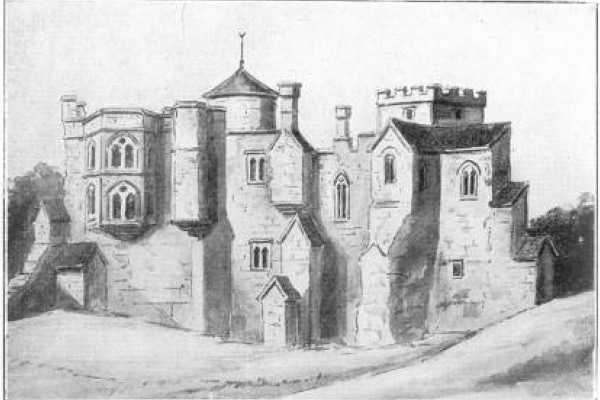

I was desperate to find out everything I could about the appearance and layout of this palace of pleasure. I had already uncovered some delicious details of its medieval appearance from my precious collection of The History of the King’s Works, including a rarely-seen view of the manor from across the park surrounding it.

With a creeping sense of anticipation, I started to dig deeper and was delighted to discover a first-hand account from a visitor to the palace, written in the early seventeenth century. It gives a wonderfully evocative account of his journey through the palace. As it turns out, it unlocked the riddle of where Elizabeth was actually held during her house arrest at Woodstock! But before we get there, let’s reimagine the setting and appearance of the palace…

The Layout of Woodstock Manor

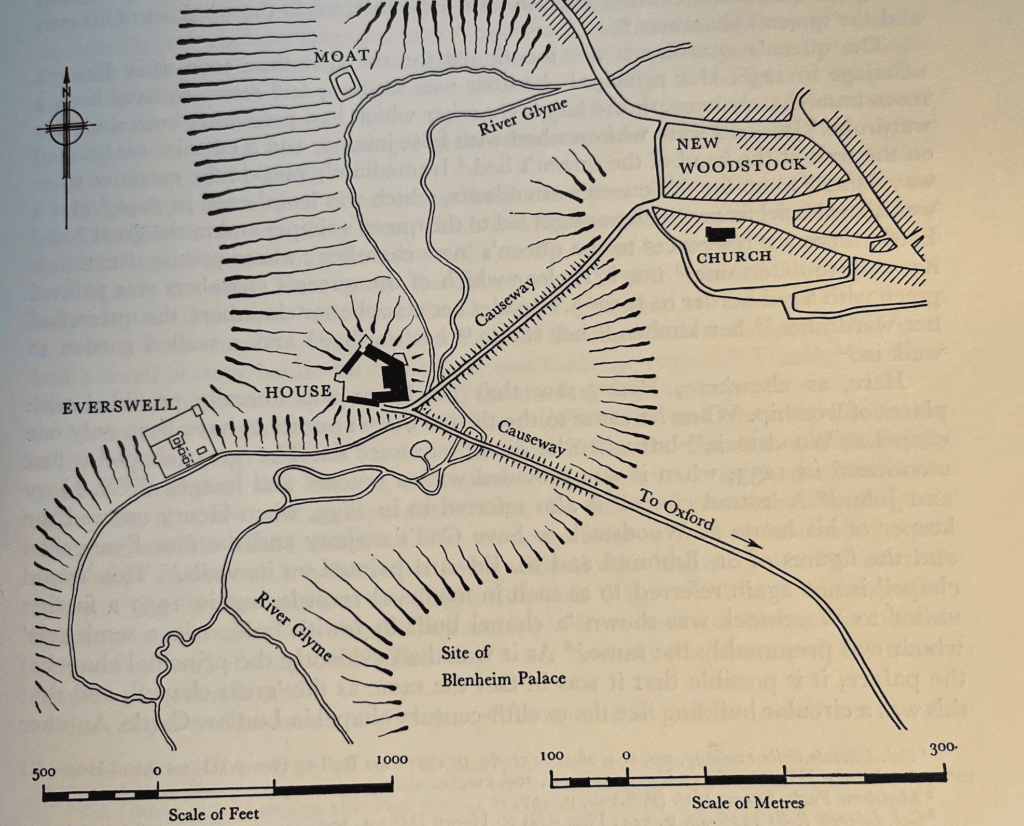

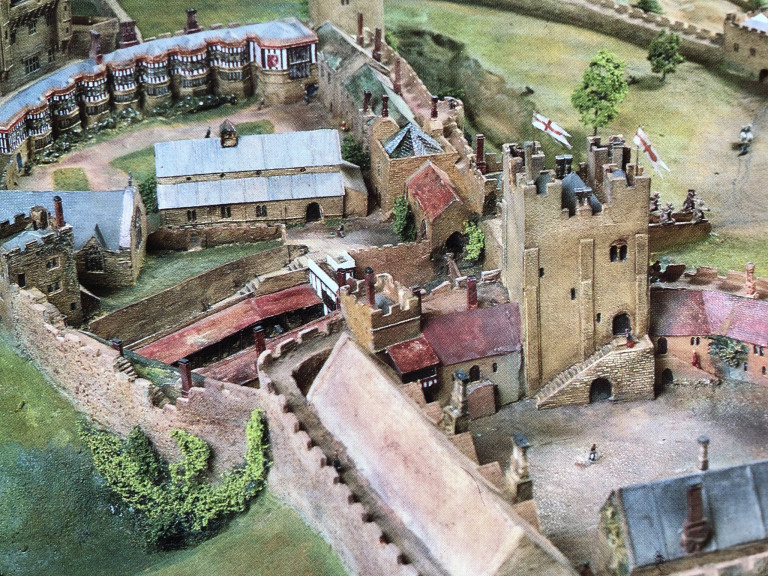

The palace occupied a raised outcrop of land, perched above a shallow valley through which the River Glyme meandered. Causeways connected it to the roads leading to Oxford, around eight miles to the south, and the adjacent village of ‘new’ Woodstock, which had grown up alongside the palace.

Our anonymous seventeenth-century traveller, enigmatically known only as ‘the Lieutenant’ describes the manor as ‘ancient, strong, large and magnificent’… He deemed it ‘sweet, delightful and sumptuous, situated on a ‘fayre hill’. A rare, early engraving of the scene is captured in Dr Plot’s Natural History of Oxfordshire (1677) (See image at the top of this post). That was before the palace was demolished and the landscape redesigned by Capability Brown.

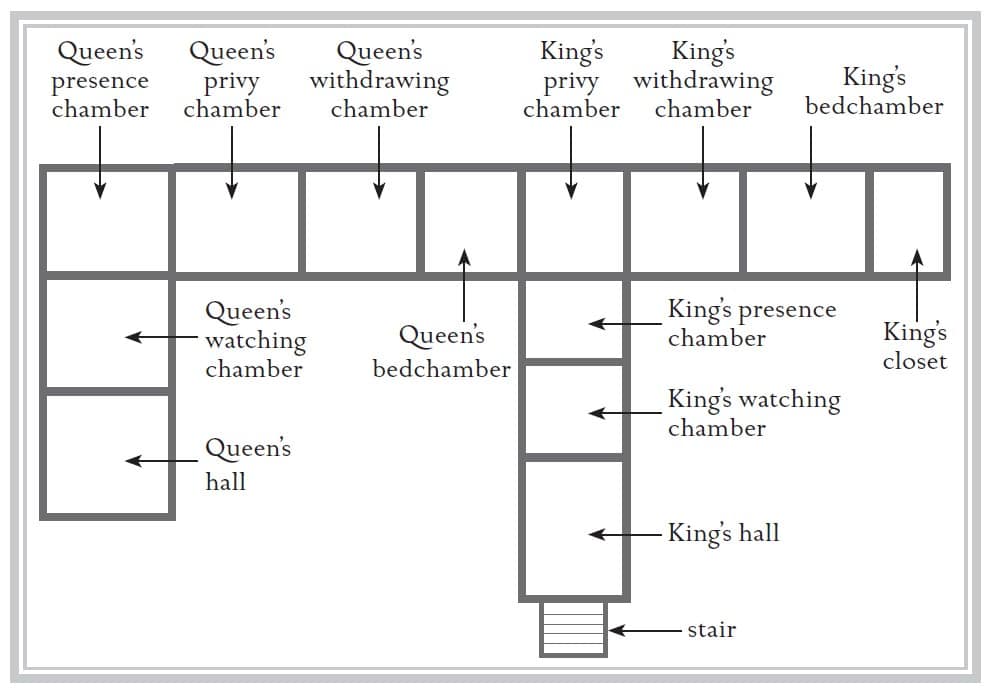

No contemporary floor plan of the medieval, or later Tudor, palace exists. However, accounts recorded in the Pipe Rolls (Financial Accounts from the English Exchequer, dating from the 1100s) reveal many of the features of the palace. Helpfully, Prof Simon Thurley has translated these into a floorplan of the royal lodgings and has kindly given me permission to use this image here – see below. (Please check out his site at ‘RoyalPalaces.com – you will find the link at the end of this blog). Remember that these lodgings comprised only a fraction of the buildings that comprised the entirety of Woodstock Manor.

At this point, I invite you to stroll through the palace alongside our ghostly guide, ‘the Lieutenant,’ and let our imagination conjure up this magnificent building once more…

The Gatehouse and Courtyards

The palace was laid out in an irregular pentagon, measuring roughly 100m long from north to south and the same east to west at its widest points. This is best seen in a map of Woodstock and its setting taken from The History of the King’s Works (see below).

The entrance to Woodstock Manor was via a gatehouse on the south side, which the Lieutenant describes as being ‘large, strong and fayre’. The History of the King’s Works (Vol. 4, Part II) notes two cant windows over the arch [Note: A cant window is a projecting window with angles, sometimes distinguished from a bow window], two porter’s lodges, two rooms adjoining these and 12 more. There was also an inscription above the gatehouse arch in ‘English rhythmical verse’. Translated, this meant: Henry the seventh built these famous houses.

This is an exaggeration of the truth. According to seventeenth-century antiquarian, Sir Issac Wake, who wrote about the manor in his book dated 1607, called Rex Platonicus, the first Tudor king built only the ‘front and outer court’ and updated and altered many of the existing, medieval buildings.

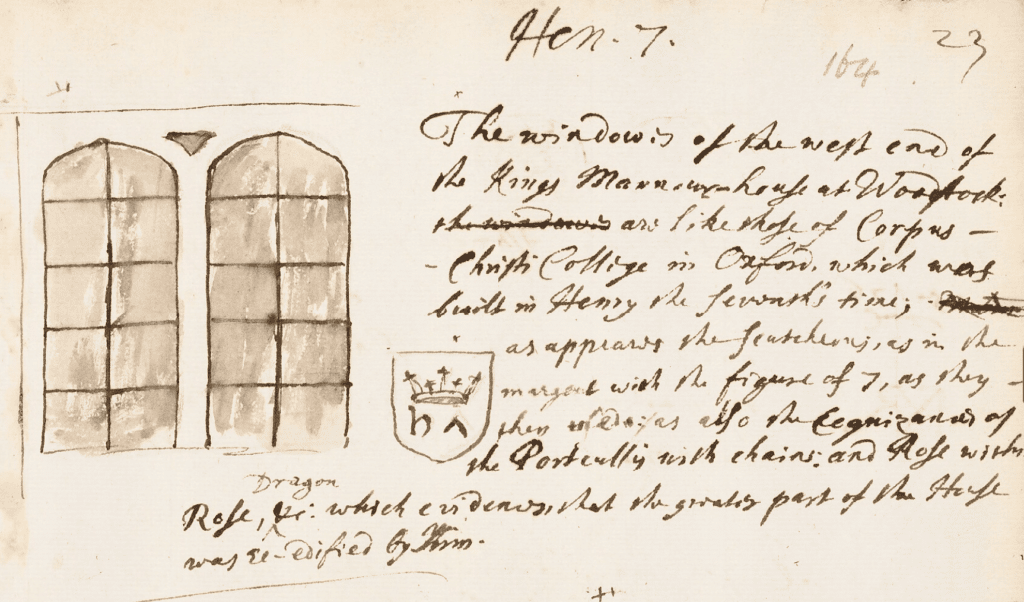

Another perspective comes from the notes of John Aubrey, an antiquary, who visited Woodstock a little later in the century, just after the English Civil War. His papers are preserved in the Bodleian Library and include a sketch of a pair of windows whose architectural style fitted with the reign of Henry VII. He notes that the emblems of the Tudor dynasty (the Beaufort portcullis, the ‘rose within a rose’ and dragons) were prevalent in and around the palace buildings. He concluded that the ‘greater part of the house was re-edified by him’.

More specifically, Simon Thurley notes, ‘Henry VII spent over £4,000 rebuilding the house. He put up a new gatehouse, a new roof for the great hall, bay windows, and a jewel house that allowed him to bring his cash when he visited.’ So, while the medieval kings established Woodstock Manor, Henry VII, founder of the Tudor dynasty, showed considerable interest in maintaining the property. He made frequent visits to Woodstock during his peripatetic progresses through England.

Once through the gatehouse, the outer courtyard sounds extraordinary, measuring 3339m2 with a fountain at its centre; this sported five spouts fed by a local spring. On the far side of the courtyard, a stately set of 35 steps ‘of freestone’ [Def: ‘Freestone’ – a type of fine-grained stone, in particular, a type of sandstone or limestone] led up to a porch. During the medieval period, this porch was noted to be wainscotted, with the wainscot, door and window shutters all painted green. Beyond the porch was the ‘church-like’ great hall, reflecting the scale of the rest of the palace.

DID YOU KNOW? Did you know that Woodstock was unusual in that it had TWO great halls, one on the queen’s, and one on the king’s side?

Into the King’s Lodgings…

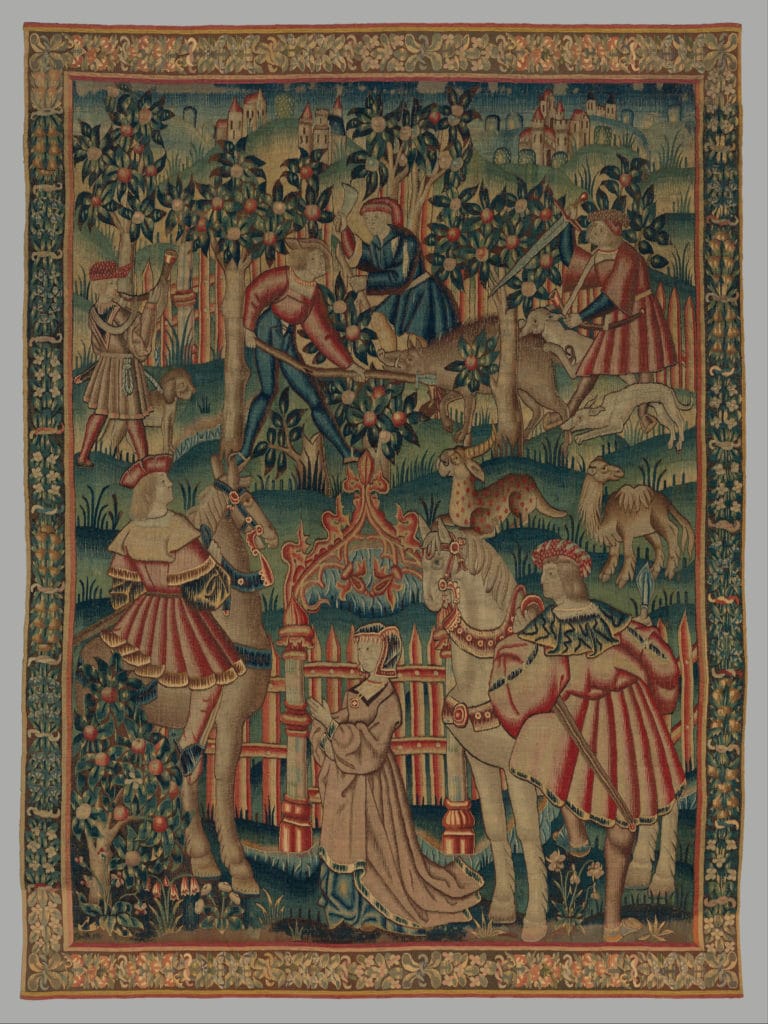

Step up into this ‘spacious’ hall, which the Lieutenant describes as having ‘2. fayre lies [ailses], with 6. Pillers, white, and large, parting either aisle, with rich tapestry hangings at the upper end thereof, in which was wrought the Story of the Wild Bore’.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the palace was the number of chapels it contained. When Henry II ascended the throne in 1154, there was only one chapel at Woodstock; when he died, there were six. The most curious was accessed from the left-hand side of the King’s Great Hall. It was unusual because it was round, like the surviving round chapel at Ludlow Castle.

The Lieutenant leaves us with his impression of the structure, which he states was a ‘neat, and stately, rich Chappell, with 7. round Arches, with 8. little windowes above the Arches, and 15. in them; A curious Font there is in the midst of it, and all the Roofe is most admirably wrought; the entrance thereunto correspondent to her Selfe, is neat, and lofty, with many curious windowes on both sides’.

Fabulous!

From here, our ghostly guide distinctly refers to ‘ascending from the hall’, into the Guard-Chamber, which ‘look’d big enough’, although he notes that ‘the Keepers were absent’, and so they were able to pass ‘uninterrupted’ into the King’s Presence Chamber. This suggests that another set of stairs connected the Great Hall to the latter chamber. The size of this hall and the stately steps leading to and from it must have been quite a majestic sight!

As you can see from Simon Thurley’s floor plan, the Presence Chamber led through into the King’s Privy Chamber. This occupied the centre of the confluence between the king’s and queen’s sides. The fact that his chamber connected directly to the queen’s bed-chamber meant that the king could pass privately between his chambers and that of his wife, should he wish to spend the night with her. This was a common, practical and cosy arrangement in Tudor royal palaces!

The Lieutenant notes that the Privy Chamber ‘lookes over the Tennis Court into the Towne’, while ‘the King’s Withdrawing Chamber, and the bed-chamber…have their sweet prospect into the Privy Garden’. This places the range of lodgings on the east side of the palace, overlooking the valley and the little town of Woodstock beyond that.

If you were to visit the site today, even though the valley has been flooded to create the eighteenth-century landscape associated with Blenheim Palace, you would still appreciate what a fine view the royal couple enjoyed from their private chambers.

Princess Elizabeth: ‘In Peril of her Life’ at Woodstock

In early 1554, a rebellion broke out in Kent. The lead malcontent was Sir Thomas Wyatt the Younger; the focus of the rebel’s anger was the Catholic Queen Mary and her proposed marriage to Philip II of Spain. Unsurprisingly, Mary’s protestant half-sister, the twenty-year-old Princess Elizabeth, was suspected of being involved. Elizabeth had been committed to the Tower for interrogation.

No substantive evidence could be found against her, and she was released two months later on 19 May.

The day’s significance does not appear to have been lost on Elizabeth, whose mother had been executed on the same day 18 years earlier. At 3 pm in the afternoon, she was brought forth from her lodgings and was met in the inner ward of the Tower by 100 men-at-arms in their blue coats, led by Sir Henry Bedingfield. He was a staunch Catholic and supporter of Queen Mary. It is noted that Elizabeth ‘asked in terror “if the Lady Jane Grey’s scaffold had been removed”. Her mother, and how precariously her own life hung in the balance, were clearly at the forefront of Elizabeth’s mind.

In fact, Bedingfield was to be her new gaoler and had been charged with escorting her, first to have an audience with the Queen at Richmond Palace before being conveyed to Woodstock Manor.

The journey to Woodstock took four days, passing through Windsor, via Eton to West Wycombe and Thame and thence onto Woodstock. The Princess was to be treated as befitting her status. She was not officially imprisoned but rather held under house arrest at a safe distance from London. However, Foxe’s Book of Martyrs states that soldiers kept

‘guard within and without the walls, every day, to the number of sixty; and in the night, without the walls were forty during all the time of her imprisonment…Sir Henry keeping the keys himself, and placing her always under many bolts and locks, whence she was induced to call him her jailer, at which he felt offended, and begged her to substitute the word officer’.

When Elizabeth was under house arrest at Woodstock, the manor was apparently in urgent need of repair, but it was far from derelict, as you might often read in accounts relating to Elizabeth’s detainment at the palace.

Woodstock had been visited by Henry VIII and the royal court on many occasions, and the History of the King’s Works mentions many payments being made through the course of the king’s reign, ‘against the king’s coming’ to Woodstock Manor. These included repairs to the smaller lodge, sited close by and to the west of the palace, called ‘Rosamund’s’, after the legend of ‘fair Rosamund’ mentioned above.

This was an extraordinary building, possibly without comparison in England. It had been built by the craftsmen of Henry II and seems to have been inspired by the Moorish design of palaces like the Alhambra, as a conduit took spring water through the chambers of the building.

This constellation of buildings included a place in which the fair maid is said to have bathed. Building accounts show it was still being maintained during the reign of Henry VIII. I can’t help wondering if Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, another pair of royal lovers, ever spent time there in the relative seclusion of the bower!

Three years before Elizabeth’s brush with Woodstock Manor, in 1551, Edward VI was also spending some money on the palace. Despite all this, a survey of the same year indicated that the palace was ‘decayed’. Decayed, perhaps, but far from derelict. However, such buildings did indeed need constant attention, for they were apt to fall apart quickly if not constantly being repaired. Thus, it is not surprising to read Bedingfield’s letter, which must have been penned before the onset of winter in 1554, stating:

[If] …this great Ladye shall remayne in this howse, there must be repacons [reparacions] done bothe to the covering of the house in lead and slate, and especially in glass and casemonds [casement], or elles neyther she nor anye yt [that] attendethe uppon hir shal be able to abyde [abide] for could [cold].

Elizabeth’s health suffered during her time at Woodstock. Bedingfield writes: ‘my ladye Elizabeth’s grace ys daylye [daily] vexed with the swellyng in the face and other parts off hir body’.

As an ex-medic, I am also intrigued by the possible causes of symptoms described in historical records and having done a brief search, I wonder if Elizabeth simply had what is known today as ‘idiopathic oedema’? This is intermittent swelling of unknown cause and, thankfully, no long-lasting effects. In an article by M.G. Dunnigan et al., they describe the syndrome and its aggravating factors: the ‘ability of short-term emotional and physical stimuli to induce the rapid onset of swelling symptoms (emotional stress, high ambient temperatures, alcohol, exercise and prolonged standing), and the remission of symptoms when these precipitating factors are removed, indicates that this process is labile and reversible.’

I’d say this episode in Elizabeth’s life could be described as ‘stressful’, wouldn’t you? This was not the least because the princess’s life was constantly threatened. While Bedingfield guarded Elizabeth to prevent escape, it protected her from would-be assassins. While at Woodstock, one account suggests that at least on three occasions, her life was in danger. In one instance, the room underneath ‘which she lay’ was set on fire; in another, the park’s keeper a ‘notorious ruffian’ was ‘appointed to assassinate her’. Finally, James Basset ‘a peculiar favourite of Gardiner’ travelled to Woodstock. Bedingfield was away in London at the time and left strict instructions with his brother ‘that no man should be admitted to the princess during his absence, not even with a note from the queen’. Thankfully, Bedingfield’s brother kept his word and Basset was thwarted in his plan.

So, now we can turn to the question of where did the Princess ‘lay’ while being held at Woodstock Manor.

As I mentioned at the top of this blog, you will often read that she was kept in the cramped conditions of the gatehouse. However, our ‘Lieutenant’ very clearly states otherwise. From where we last left him, his tour continued by crossing back through the King’s Privy Chamber and he notes, ‘into the Queens Bed Chamber; that, where our late vertuous and renowned Queene was kept Prisoner in.’

The Lieutenant goes on to detail the sequence of rooms laid out on the queen’s side (as illustrated in Thurley’s diagram), including the presence of a Queen’s Great Hall, accessed via the ‘Wardrobe Court’ and a Counsell Chamber curiously Archt [?arched], and a neat Chappell by it, where our Queene heard Masse’. He is, of course, referring to Elizabeth.

Thus, it seems he was clear that Elizabeth was not held in the gatehouse but in the queen’s lodgings. I had always been troubled by this account of the gatehouse being used as the place in which she was held, and this new information makes much more sense (to me, at least!) Elizabeth was not officially under arrest. Mary had given orders that she was to be treated according to her status, and while in the Tower, it seems that she was lodged in the Royal Apartments, which had once housed her mother, Anne Boleyn. Why then bring her to Woodstock and keep her in the gatehouse?

We also hear of her being allowed to walk in the privy garden. This was connected directly to the royal lodgings. Thus, access to the garden would have been easier to control from this eastern side of the building. Why risk walking the Princess across the courtyard from the gatehouse to reach the gardens when you can use a privy stair? I’d be interested to hear what you think and whether you, too, had always believed that the gatehouse was the place of her ‘incarceration’. Let me know in the comments below.

Thankfully, Elizabeth was taken back to London the following year and subsequently released. Clearly, her difficult time at Woodstock Manor did not put her off. She would return and visit the palace as queen on several occasions.

However, if both Foxe and Holinshed are to be believed, she couldn’t quite resist leaving behind a record of her time there. Both chroniclers record the now famous rhyming couplet said to have been engraved by Elizabeth with a diamond onto a pane of glass: Much suspected by me, Nothing proved can be, Quoth Elizabeth, prisoner. While an Elizabethan traveller, who also came to the palace during Elizabeth’s lifetime, in 1597, records that while ‘in peril of her life’ at Woodstock, the young process had written in charcoal on a window shutter the following poem:

O FORTUNE! how thy restless wavering State

Hath fraught with Cares my troubled Wit!

Witness this present Prison whither Fate

Hath borne me, and the Joys I quit.

Thou causedest the Guilty to be loosed

From Bands, wherewith are Innocents inclosed;

Causing the Guiltless to be strait reserved,

And freeing those that Death had well deserved:

But by her Envy can be nothing wrought,

So God send to my Foes all they have thought.

ELIZABETH PRISONER.

This was a treacherous time for the young princess, a time when her life was under threat from ardent Catholics who feared her Protestant inclinations. However, Elizabeth was nothing if not a survivor, and she survived unscathed from her ordeal.

I returned to Blenheim Park several weeks after writing this blog and headed straight for the plinth. My sense of frustration was gone. In front of me, the ghostly palace rose from the plateau of land on which it once stood, the lake dissolved away, and I saw again the causeway crossing the shallow valley below. There it was in all its majestic glory, and I could say that I finally knew this place intimately.

To listen to the podcast associated with this blog, click here.

To visit the site of Woodstock Manor in Blenheim Park, check out the Blenheim Palace website...and, of course, do make sure to visit the later palace too. It’s a World Heritage Site, the birthplace of Winston Churchill and the only non-royal palace in England. During the summer, there are often jousts held on the grounds, taking us back to its earlier, medieval and Tudor history.

Do let me know your stories and recollections of visiting the park at Blenheim in the comments below!

Sources

https://www.royalpalaces.com/palaces/woodstock/

In the Footsteps of Anne Boleyn by Sarah Morris and Natalie Grueninger. Amberley Publishing. 2013.

The History of the King’s Works, Volume II: The Middle Ages, ed. by H.M Colvin. London: HM Stationery Office, 1963 p. 1009-1017.

The History of the King’s Works, Volume IV: 1485-1660, ed. by H.M Colvin. London: HM Stationery Office, 1982. p. 349-355.

A Chronicle of England During the Reign of the Tudors from AD 1485 to AD 1559, by Charles Wriothesley.

A relation of a short survey of 26 counties observed in a seven weeks journey begun on Aug. 11, 1634, by Captain; Legg, L. G. Wickham (Leopold George Wickham), b. 1877; Ancient; Lieutenant. p.118-119.

John Aubrey’s Oxfordshire Collections: An Edition of Aubrey’s Annotations to his Presentation Copy of Robert Plot’s Natural History of Oxfordshire, Bodleian Library Ashmole 1722, by Kate Bennett. p.77.

Actes and Monuments, by John Foxe, p294-295.

The Bedingfields of Oxborough, by Katherine Bedingfield p. 26 – 31 https://archive.org/details/bedingfeldsofoxb00bedi/page/26/mode/2up?view=theater

Unexplained swelling symptoms in women (idiopathic oedema) comprise one component of a common polysymptomatic syndrome, by M.G. Dunnigan, J.B. Henderson, D. Hole, A.J. PelosiQJM: An International Journal of Medicine, Volume 97, Issue 11, November 2004, Pages 755–764.

A Journey Into England, by Paul Henztner (1598). Horace Walpole, ed. 1757.

Fantastic article! I am among your former colonists, and love studying English medieval and Tudor history, with a special focus on the buildings where my favorites lived, fought, and are buried. Spent a week in Woodstock staying at the MacDonald Hotel. Visited Blenheim, of course, though being “too modern” for my special favor, I had a lovely afternoon touring and a delightful lunch with wine outside overlooking the fabulous fountain garden. At the time I did not know there was a plinth marking Woodstock’s site, else I’d certainly have hiked to it. I did walk back to Woodstock, sat on the grassy incline along the lake, and photographed a beautiful pheasant there. On all these type outings I am lost in a reverie imagining Edward and Philippa, John of Gaunt and Katherine, or Henry and Mary de Bohun walking and talking there. I imagine you do the same!

I certainly do! One of my favourite things. And now you have the perfect excuse to return to Blenheim, Kathye! ?

I found that really interesting. thankyou. i will think about this research when I visit Blenheim.

Wonderful! Have a great visit…?

Thank you very much for this article! We are now able to envision the long-lost Woodstock Manor and we finally have an answer to the whereabouts within the palace for the imprisonment there of Elizabeth I in the mid-1550s. With regard to the privy garden (herbaria) at Woodstock, I read that there were actually two – one on each side of the king’s chamber. For details, see John Steane, The Archealogy of the Medieval English Monarchy. London; New York: Routledge, p. 117. Thanks again!

Hi Brandon! Thank you for your comments. So glad you enjoyed the article and great reference for us to dive into.

My sense of frustration was gone. In front of me the ghostly palace rose up from the plateau of land on which it had once stood,

Many thanks for this article, You would enjoy ” WOODSTOCK AND THE ROYAL PARK, 900 years of History”

written by five Woodstock authors in 2011 to celebrate the 900 years since Henry I built the stone wall around his Park and zoo. It is almost sold out but I have a few copies @ £14.95. Henry VII was so proud of Woodstock that he held the proxy marriage of Prince Arthur here to impress the Spanish. Best regards Robert Edwards

Hello! Do you have a link to purchase? I – and others -might be interested. Thanks!

Hello young lady, I am in the middle of reading Robert Plots “History of Oxfordshire” and wanted to find a better picture of Woodstock Manor than the one he used. I found one and it was with your essay on Woodstock in the Tudor Travel Guide. I read a lot about English history , my favourite being the Tudors and Stuarts. I live in Leics so was very interested in the finding of Richard III in the Leicester car park and the reign of the new monarch Henry VII. Until I found your essay on Woodstock manor I did not even know of its existence . I did not know about Henry re-developing the manor house or about Elizabeth’s imprisonment there by Bloody Mary . What a pity they ever flooded the valley to create un-natural lakes – it would be better to see it as nature intended- like in Plot’s picture. Just to say a big thank you for the info you have imparted , I found it really enjoyable and you have added to my knowledge of British history. I live ,as already said in Leics and within a couple of miles fro Bradgate Park where there is another interesting manor house from the time of Henry Grey, his wife Frances (Nee Brandon) and their three daughters Ladies Jane, Katherine and Mary Grey . A wonderful place , you should visit it

I don’t know your name but you say you were a medic so Miss Medic I appreciate your essay ,it must have been based on a lot of hard but interesting work. All the best John Burt

‘Young Lady’ – You can come agin! : ) Thanks for leaving this comment. I am delighted that you found the article to be of use. I too wish they had not flooded the valley – or torn the palace down. Damn those Georgians!?