Mary Howard: The Indomitable Tudor Duchess

Mary Howard, Duchess of Richmond, was a force of nature. The youngest daughter of the 3rd Duke of Norfolk, she was at odds religiously with most of the rest of her Howard family, went head-to-head with Henry VIII in a battle for money and flatly refused to be pressured into remarriage when three of the most powerful men in the land plotted her future with Thomas Seymour. Mary, came alive for me when I was writing my novel about Anne Boleyn. She served Anne and was probably deeply influenced by the queen’s reformist leanings. If you are unfamiliar with her story, read on to find out more about this fascinating woman.

Note: This blog is based on an interview with Nikki Clarke, Senior Lecturer in Early Modern History at the University of Chichester, made for my podcast, The Tudor Travel Show.

Mary Howard: Birth and Early Years

Sarah:

So today, it’s all about Mary. For people who perhaps don’t know that much about Mary Howard, maybe you could outline who she was and who were some of her key Tudor relations?

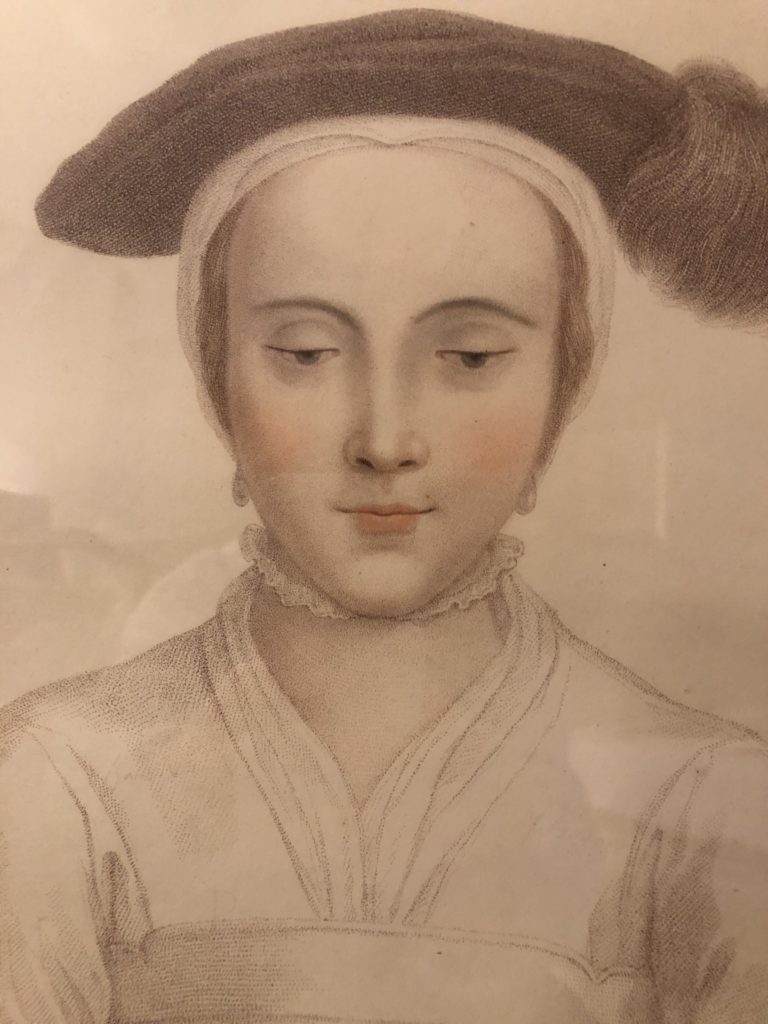

Nikki: Yes, absolutely. Mary Howard was the younger daughter of Thomas Howard, the third Duke of Norfolk and his second wife, Elizabeth Stafford. That made her the granddaughter of Edward Stafford, Duke of Buckingham, who was executed in 1521. She’s the sister of Henry Howard (who’s often called ‘the poet Earl’). He was the Earl of Surrey; he was executed in 1547. She is the first cousin of Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard, Henry VIII’s second and fifth wives, respectively.

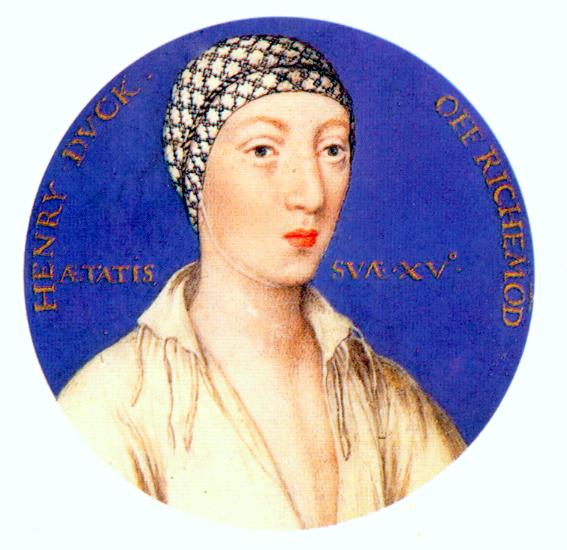

She married Henry VIII’s illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond, which made her the King’s daughter-in-law. This related her by marriage to the Tudor dynasty itself. His niece, Margaret Douglas, who’s the daughter of his older sister, Margaret Queen of Scotland, is Mary Howard’s best mate at court. Through the Howards as well, she’s more distantly related to a lot of other courtier families like the Shelton’s, Francis Bryan, the rest of the Boleyns and so on.

Sarah:

Why are you so interested in her?

Nikki:

I wrote about her in my book on the Howard women because she’s a bit of a force of nature! Unlike some of her other female relatives, especially her mother, she does serve in her cousin, Anne Boleyn’s, household and she’s part of that contemporary crowd at court. She gets widowed unexpectedly in 1536, and then started a bit of a fight with her father-in-law, the king, over money – and eventually won. She manages to circumvent a second marriage when all the powerful men around her are trying to marry her off for a second time. She refuses and gets away with it.

Then, as the 1540’s progress, she also starts to hold very different religious beliefs from some of her immediate family. Her father, the Duke of Norfolk, is known for having been a strong, religious conservative, but Mary Howard began to follow the reformed faith. So, I was interested in her because she did things differently to some of the rest of her family. I was also interested in the way that family functioned in the Tudor court. We have this image of girls doing as their fathers told them, with the whole family coming together as a coherent political force, but that’s not always the case.

Sarah:

I love the fact that you use the phrase ‘force of nature’ because that’s how she seems to me, as well. She was a woman who knew her own mind. So, maybe we could go back to the beginning and try and understand a little bit more about Mary’s early life. Do we know much about it, where she was brought up and with whom – and did she receive that classic humanist education which was being introduced at the beginning of the sixteenth-century?

Nikki:

We don’t know a huge amount about Mary Howard’s early days, as is so often the case with early modern women. We do know that she’s born sometime in 1519 – the same year as Katherine Willougby, who later became Duchess of Suffolk. Interestingly, we do have a few details about her birth that may or may not be true and are a little bit harrowing.

Sarah:

Oh, dear, go for it!

Nikki:

According to Mary’s mother, Elizabeth Stafford, Elizabeth was physically assaulted by her husband, the Duke of Norfolk, during her labour with Mary. Apparently, when she’d been in labour with Mary for two nights and a day, he dragged her out bed and around the house by her hair and wounded her in the head with a dagger.

He wrote later to Cromwell specifically to deny this. Norfolk said that Elizabeth had put this story about just to slander him. He said that he could prove by witnesses that she’d had the scar on her head months before she gave birth to Mary; he thought no man would treat a woman in labour that way and he would not have done so for all that he was worth. So, we just don’t know whether that is true, whether it’s partly true, or what was going on really, but it does suggest that Mary Howard’s entry into the world wasn’t necessarily smooth.

Mary Howard Arrives at Court…

Sarah:

When does Mary Howard first come to court?

Nikki:

She probably made the odd visits to court as a child. She would have spent most of her time in childhood in the family’s houses in East Anglia. So Tendring Hall in Essex, Kenninghall a bit later and probably Framlingham Castle after her grandfather’s death in 1524. She would have been there with her older sister, Catherine, and her brothers, Henry and Thomas, at least for some of that time.

We don’t know anything about her education, really. We do know that her older brother, Henry, was well educated but that’s probably because he was part of her future husband’s, Henry Fitzroy’s, household, and the two were educated together along humanist lines at Sherrif Hutton Castle in North Yorkshire. The few letters that we have from Mary Howard from a little later, show that she’s able to read and write, which is usual for a noblewoman at this point. There are sources that suggest she read scripture in English herself and she also had books dedicated to her. It’s also reasonable to suppose that she probably knew some French, but beyond that, we just don’t know about her education, unfortunately.

She probably comes to court as a child here and there, but her first recorded appearance as being in service at court is not until September 1532. That’s when she attends Anne Boleyn, at the point that Anne is made Marquis of Pembroke at Windsor Castle. By that point, Mary is already betrothed to Henry Fitzroy and she’s about 13 years old.

Sarah:

That’s where I got entangled with Mary when I was writing about Anne Boleyn. I was curious about the relationship between the two women because, as you pointed out there, Mary was very prominent in the ceremony that elevated Anne to become Marquis of Pembroke. Obviously, she was an important person from an important family, but I kept coming across her being present in Anne’s household. What do we know anything about the relationship between Anne and Mary?

Nikki:

Not a lot. It’s normal for her to have entered the court at about that age as a maid of honour. We don’t know a lot about the relationship between the two women. We do know that Mary later gave John Foxe, the martyrologist, information and anecdotes about Anne that he used in his book of martyrs. For instance, information about Anne apparently always carrying money that she gave to the poor in alms everywhere she went. That anecdote came from Mary Howard and that does suggest at least that Mary has positive memories of Anne.

Sarah:

So we simply don’t know whether Anne had an influence on her or on her later reformist beliefs?

Nikki:

We don’t have any direct evidence, but it is entirely possible that Anne does influence Mary religiously. Anne is said to have been of a reformist leaning. Her household is the most likely place for Mary to have encountered those ideas. Anne supposedly kept an English Bible in her privy chamber for anybody to go and read, for instance. So that’s something Mary would have found when she was there. It is also the case that Anne apparently arranged Mary Howard’s marriage for her before Mary came to her service.

Sarah:

Do tell us more about that. How involved was Anne in putting her forward as a potential wife for Henry Fitzroy?

Nikki:

It was a bit of a muddle to be honest, partly due to plague. Mary is the younger daughter. She has an older sister, Katherine, who was forgotten about by historians for many years because the records get a bit confused. Her older sister, Katherine, got married to the Earl Derby in 1529. The Earl of Derby was still a minor at that point; he was under 21. So Norfolk had bought the last year of Derby’s wardship and then, slightly illegally or at least questionably, because he didn’t get Royal permission, he swiftly married him off to his oldest daughter, Katherine.

That is a really lucrative match for the Howards – politically, socially and economically. So it’s like, yeah, good, we got this! Great! At that point, Mary Howard was betrothed to the heir to the Earldom of Oxford which, again, was a good match. The Howards and the De Veres had married before, but that betrothal got broken in 1529 when the king seemed favourable to her marrying Henry Fitzroy instead, which was a better match politically and socially.

Her older sister, Katherine, who’s married to the Earl of Derby died very unexpectedly in March 1530, only a few weeks after the marriage of the plague. This is no doubt devastating for her parents, and for her whole family, but it also creates a political issue because that marriage that she had to the Earl of Derby was too valuable to lose. So, as well as grieving the loss of their daughter, Norfolk and Elizabeth are immediately wondering how can we hold onto this?

Mary Howard’s mother, Elizabeth, thinks the obvious choice is for Mary to take Katherine’s place and marry Derby in her stead. But, because there have been talks going on about her marrying Henry Fitzroy, Norfolk is keen to carry on with that. Anne Boleyn then gets involved. Anne is very keen to cement her own position in the royal family, by creating other connections to the Tudors by marriage. If the Howard family is already part of the Tudor dynasty, then it bolsters Anne’s own position, because it looks less bizarre when she marries the king. So she sticks her nose in and insists that Mary should marry Henry Fitzroy and not the Earl of Derby. Anne and Mary’s mother, Elizabeth, seem to have a bit of a fight about it. High words are exchanged and Elizabeth nearly gets dismissed from court, but Anne eventually gets her way. Mary’s mother, Elizabeth, later said that they didn’t even have to pay any dowry because Anne got the marriage for them by persuading the king.

Sarah:

So that’s an interesting relationship between Elizabeth and Anne, as well. So they didn’t get on so well?

Nikki:

No, they are not mates. Elizabeth has been a lady waiting to Katherine of Aragon for 16 odd years, off and on.

Sarah:

Anne, of course, at this time was still very much in her ascendancy. So it’s not surprising really that she probably got her way by wrapping the King round her little finger.

Nikki:

Yes, I think so. Anne is also, I think, very anxious and quite afraid. Yes, she’s in the ascendancy, but it’s by no means a done deal in 1529/1530. So, I think anything that she can do to help herself and help her own position, she’s going to go for – and woe betide anyone who gets in her way!

A Royal Marriage Arranged…

Sarah:

So when and where did Henry Fitzroy and Mary Howard finally marry? What do we know about that?

Nikki:

They married in 1533 at Hampton Court Palace. Mary herself probably didn’t have much of a say in the matter, but we don’t need to assume that she’s doing it against her will either. Daughters mostly do want the same economic and social things that their parents want for them. Romantic love isn’t usually considered part of the equation for aristocratic marriages. So, we don’t really know whether it’s a good match temperamentally. It’s really hard to know what they’re like, especially because Fitzroy died so young and they marry when they’re still teenagers, so it’s hard to tell.

Sarah:

They didn’t get a chance to live together, did they? Obviously, there were fears about Mary conceiving too early and the perils of childbirth?

Nikki:

Yes, pretty much. They never did co-habit as both of them were considered too young. It was normal for marriages to be arranged or even formalised, between teenagers, because Church law stated that girls can get married at 12 and boys at 14. But generally, by that time, it’s thought to be a bad idea for them to actually crack on with married life and having sex and kids and so on. Yes, it’s partly because they don’t necessarily want 13-year-old girls giving birth (by this point they’ve moved on a little from the Margaret Beaufort scenario), but it’s also because they think it’s bad for boys to be doing that too young, partly in memory of Prince Arthur, I think.

A Duchess in Hot Water…

Sarah:

So, now should we fast forward a little bit because Henry Fitzroy doesn’t last too long. What happens to Mary when he dies in 1536?

Nikki:

Well, her life hadn’t really changed much up to that point, except that she now had the title of Duchess of Richmond. Thus, she had status outside of being the Duke of Norfolk’s daughter. But because they’d never lived together and they weren’t supposed to do that until the age of 18, I think life for both of them had continued as it had before. So when Fitzroy died, it’s really hard to know whether Mary was sad. Possibly she was not all that sad; she knew him, but there’s no surviving evidence that they had a very strong, close, personal relationship.

He gets ill and he dies quite unexpectedly in July, 1536. We don’t know what he dies of; we rarely do in this period and it’s too difficult to diagnose over a 500 year distance. But it’s safe to say people didn’t expect him to do that. This is yet another bad event in a year of awful events for Henry VIII. It’s been a month or so since Anne Boleyn’s execution, and it ties in with another event that involves Mary in a really interesting way. July 1536 is the same month that Henry VIII’s niece, Margaret Douglas’s secret marriage to Lord Thomas Howard is discovered and that’s relevant because Mary and Margaret are best buddies.

Sarah:

Can you tell me a little bit more about when they became friends and were there any particular ties that bound them together?

Nikki:

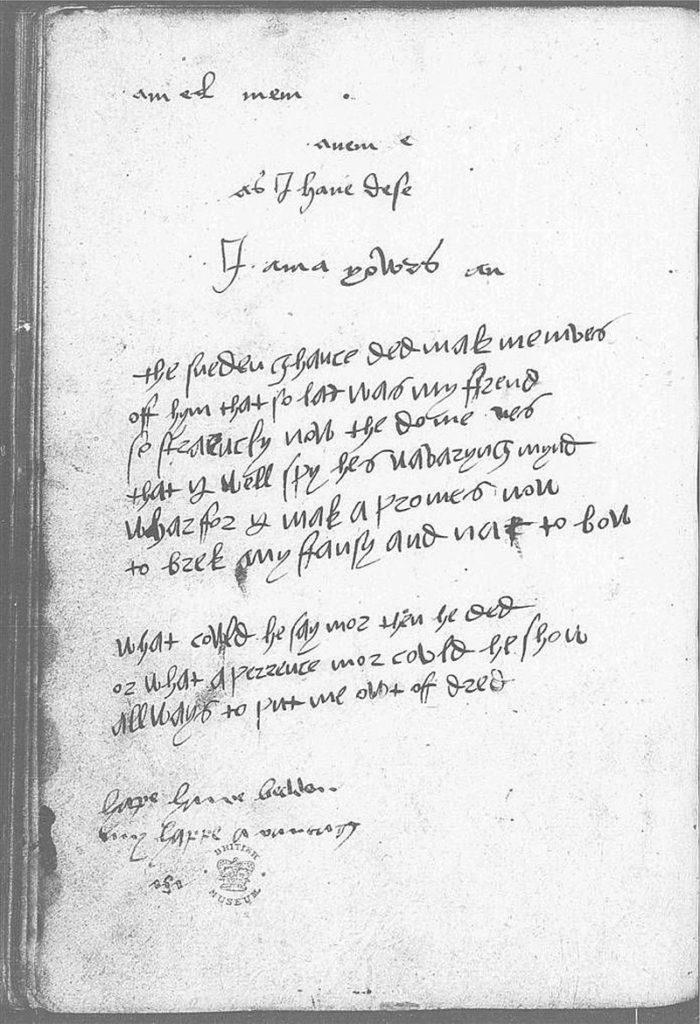

We don’t really know, but probably not until the early 1530s, once both of them were at court. Margaret, I think, is a little older than Mary Howard. Margaret is the daughter of Henry VIII’s older sister, Margaret. The latter Margaret is, or was, Queen of Scotland and Margaret Douglas is her daughter. The two of them were in service to Anne Boleyn and they, along with Mary Shelton, make a little trio of ‘Ms’. There’s a whole crowd of them and some of the boys as well; Thomas Wyatt, Mary’s brother Henry, Earl of Surrey. The whole crowd is like the bright ,young things of the 1530’s – they’re really sharp and witty and clever.

We know this because Mary Howard owned a blank manuscript book that she used to pass around the whole circle for them to write their favourite poems into, including original prose. Then they would annotate it and write banter to each other in the margins. We know this because that manuscript still survives. It’s called the Devonshire Manuscript and it lives in the British Library. Also, there’s a whole Wiki book of it online. Somebody has transcribed the whole lot and included discussion about the different handwritings, who they belong to, the links between everyone involved and things like that – it’s an amazing source.

Sarah:

I can just imagine that. It’s so clear and vivid; these bright, young things taking the court by storm. It’s wonderful! Now, let’s move the story on to the end of Mary’s life. What happens then to Mary? She doesn’t remarry, does she, but she does get embroiled in a few ‘situations’. As you hinted at at the beginning of our discussion, life doesn’t get dull for her at this point at all, does it?

Nikki:

No! Right before her husband dies in 1536, Margaret Douglas has a secret affair with Mary’s half-uncle, although he’s not much older than her; it’s a bit of a complicated family tree. His name is Lord Thomas Howard. The only way that the couple can meet is in secret, otherwise, they’d be noticed, but it is really hard to meet people secretly at court. So, you need a helper – and Mary is that helper. So, she and Margaret wait until everyone else is out of the room and then they’ll let Thomas in. Mary is there when Margaret and Thomas married secretly at Easter 1536. And she knows this is not a good idea; it is technically illegal but, you know, Margaret’s her mate and hey, Margaret’s marrying a Howard and that helps the Howard family out, right? I’m sure it’s fine. Well, reader, it was not fine!

Sarah:

What happens next?

Nikki:

It gets discovered in July 1536 and the king is predictably furious. The big problem with this is that Anne Boleyn has literally just been executed. That means her daughter, Princess Elizabeth has been made illegitimate. So, the king now has two illegitimate daughters and no son; the succession is not looking great. So, for his niece to go and marry some Howard younger son is not cool. But, they can’t legally undo it because Church law upholds even clandestine marriages. So, instead the couple get imprisoned in the Tower and then Margaret gets moved to Syon Abbey. In the meantime, Lord Thomas gets attainted for high treason.

They spin some kind of charge saying, well, he was obviously trying to get at the throne. He is not executed, but he does die in the Tower a year later and Margaret remains in Syon Abbey for some time. Now, Mary Howard should have got into some quite serious trouble for being their go-between and the fact that she didn’t is probably because, at about that time, there were rumours that the king is about to make her husband, Henry Fitzroy, his heir to the throne. Now he can’t do that and simultaneously imprison his daughter-in-law without looking a bit daft. Unfortunately, Fitzroy then dies very unexpectedly, slightly later that month. So, that plan is scuppered and by that point, it seems that there’s so much else going on that the will to do anything to Mary seems to have just disappeared. So she gets away with it.

Mary Howard: An Independant Widow

Sarah:

Quite incredibly, Mary chooses to never remarry, as might have been expected of her, despite the fact she came under a lot of pressure to do so. Can you tell us more about the circumstances surrounding that episode in her life?

Nikki:

Yes, indeed. So, Fitzroy dies and I’m sure the King is really grieving, but it’s very difficult to know whether Mary is. It’s hard to know how much and how well she really knew him. What she does immediately is to go back to her father’s house at Kenninghall, because she doesn’t, at this point, have anywhere else to go. By that time, her mother isn’t there anymore because her parents’ marriage has broken down. So, Mary is at Kenninghall with her brother’s wife; her father’s mistress, and maybe also her youngest brother. What happens next is a fight over money.

Again, this is very Tudor; they like to do this. Normally aristocratic marriages are made with a kind of pre-nup agreement. The bride brings a dowry with her, which is usually cash, and in return the groom’s family agree a number of estates and say that the income from those will be hers if she gets widowed. That is called a jointure. Mary ought to be entitled to jointure from the king, who is her father-in-law, but we know that Henry doesn’t like to pay money if he doesn’t have to – and this jointure would have been about a thousand marks a year, which is not a small sum.

So, he claims that he doesn’t have to pay her anything because the marriage was never consummated. Now that sounds like a nice, handy get out clause, but by law he’s wrong and plenty of lawyers and clerics gradually start telling him so. Mary is also not prepared to just give this up without a fight. She expects her father, the Duke of Norfolk, to fight her cause for her at court. However, she doesn’t seem to appreciate that that’s tricky when you really don’t want to annoy the king!

Sarah:

Yes, that’s a dangerous plan, isn’t it?

Nikki:

Yes, it is and a bit unfairly, she thinks he’s just not doing his best for her. But we know that he is trying because every letter he writes to Thomas Cromwell over the next few years has a line in it about his daughter’s cause. So he is trying, but nothing really happens. We know at this point that her father is nervous about her future. He complains that there’s no one of decent status for her to marry next.

Around the beginning of the Pilgrimage of Grace rebellion in the autumn of 1536, he expects that he’s going to be sent North to deal with it. This is because when you have a rebellion, you need a Howard because he’s a first-rate good soldier. At that point, he writes to Thomas Cromwell that he’s worried about leaving Mary behind with the question unresolved in case “she should bestow herself other than I would she should”. Basically, he’s worried that she might run away and marry someone unsuitable. That is quite an admission of lack of patriarchal control!

Sarah:

Yes, you’re right!

Nikki:

Yes. It’s basically an admission that ‘I can’t control my daughter’.

Sarah:

I guess that also shows how headstrong Mary must have been at that stage?

Nikki:

Yes, I think it does. It doesn’t actually happen, but the fact that he fears that it seems to say quite a lot. So, she carries on consulting her own legal counsel and then she starts emotionally blackmailing her father into letting her go to court to sue the king herself. He writes to Cromwell rather anxiously in a tone of ‘I’m not sure if this is a good idea, but she’s weeping and wailing and she won’t shut up’ and at the end of the letter he said he’d never communicated with her in any serious matter and he didn’t expect to find her as he does: ‘too wise for a woman’.

Sarah:

Brilliant, absolutely brilliant! What happens next?

Nikki:

Well, behind her back, Norfolk, Thomas Cromwell and the king cook up another plan. They realise that if they can marry her off again, then the question of that jointure can be quietly forgotten because any finances of a widow become her new husband’s. If they choose this new husband carefully, he will never pursue the matter and so it can just die a quiet death. So, they decide on Thomas Seymour with his agreement. He is the younger brother of Edward Seymour and of Jane Seymour, who is the next queen. He’s not a bad match, although he doesn’t have the same level of status that the Howards do. Still, Mary comes to court and it’s unclear exactly what exactly happens, but it seems that they present her with this plan. She says, “No, I think not!” and leaves, going straight back to Kenninghall. Norfolk is left embarrassed and having to apologise for her.

Sarah:

Do we know why she objected to Thomas Seymour?

Nikki:

No, not exactly. My guess would be that it’s partly a status thing. He’s a younger son; he has no title and she’s just been Duchess of Richmond. I think it’s that this is a step down for her. I think also that she simply didn’t want to remarry again at all and, particularly, I think she wouldn’t want to give up that fight over her jointure and just let it die. In addition, I suspect she doesn’t appreciate being so tightly controlled by the men around her for all that she accepts that a degree of that is going to be normal. It’s not that she’s a kind of proto-feminist or anything, but being a widow generally is often a better bet than being a wife.

The Interrogation of Mary Howard

Sarah:

So where are we now in our story with Mary? At some point, at the end of Henry VIII’s reign she very bizarrely gets embroiled in the downfall of her brother. I always find that very intriguing. Can we talk a little bit about that?

Nikki:

Yes, absolutely. She does win the jointure fight. In 1538, the king does cave in and gives her estates to pay her jointure. So Mary wins that fight and she doesn’t remarry. By the end of the reign, things get rather odd. Mary’s Howard’s other, Henry, is arrested on a charge of treason, swiftly followed by her father, the Duke of Norfolk, in December 1546. In January 1547, her brother is executed and the charge is of treason but it’s really odd. It’s related to the heraldry that he’d been using.

So he’d been using royal arms that he wasn’t entitled to, and that gets quite bizarre and heraldically complex. Henry VIII is not in great health by this point and it’s becoming obvious that there’s going to be a minority reign of Edward VI. So, everybody is shuffling into position for Regency. In this atmosphere, Henry Howard had been walking around, talking about how powerful his father was going to be in the next reign and then using royal arms he wasn’t entitled to. Now, if you are a very paranoid king or, indeed, you’re somebody who’d quite like to get the Howards out of the way, it’s not difficult to persuade the king, that this is a bid for the throne and that they should really be locked up. It’s not a smart move on the part of Henry Howard.

Sarah:

No, and I guess the Seymours might have been behind that? I imagine they had the most to gain from getting the Howards out of the way?

Nikki:

Yes, among others. The court is pretty divided over religion at this point. Norfolk is known as a staunch conservative, although Mary Howard and her brother are known as reformers. So it’s not 100% ‘let’s get the conservatives out the way’, but it is true that some of the other powerful reformers do want Norfolk and his Catholic influence gone. He is the real target here. Henry Howard is a kind of distraction.

Sarah:

Is she called to testify against him or does she give evidence against her brother in some way?

Nikki:

They get arrested. The next step is to get witness statements or testimonies, and these are known as ‘depositions’. Who else do you ask about somebody’s heraldry but their family? Annoyingly, those depositions don’t survive anymore. They got burned in the Cotton fire in the eighteenth-century, but they were seen in the seventeenth-century by Lord Herbert of Cherbury, Henry VIII’s first biographer. He wrote about them so we do have a sense of what they said and there is some other evidence that tells us how this went.

A couple of days after the arrests in December 1546, some of the King’s commissioners, who Mary Howard will have known, arrive at Kenninghall early in the morning. They found Mary and the Duke’s mistress, Bess Holland, only just got up and not yet dressed. They’ve been sent to bring news of the arrests, to search the house and to question the people who were there. Mary’s reaction shows that she knew immediately that this was really serious. In their report they described her as ‘sore perplexed, fumbling, and likely to fall down’. The women are told they’d be questioned and advised to cooperate. Mary very sensibly says something along the lines of, ‘alright, I won’t hide anything from you’, especially if ‘it be of weight’ and that she would tell them everything as she remembered it. What else do you do in that situation?

Sarah:

Yes, quite. It’s very sensible.

Nikki:

She seems to have grasped pretty quickly that her father is the real target here, but she is asked about a lot of stuff to do with her brother. So, according to Cherbury, a key point of her deposition was the way she told the story of her father’s second attempt to marry her to Sir Thomas Seymour in 1546 and her brother’s reaction to that. She had declined that match again, apparently because ‘her fantasy would not serve to marry with him’.

Surrey had apparently told her that instead of refusing outright, she should have prevaricated, used that time to get into the king’s affections and become his mistress, and then ‘bear as great a stroke about him as the French king’s mistress. That’s a pretty big deal! Surrey’s apologists say that was a sarcastic suggestion and that Mary shouldn’t have taken him seriously, because he’s essentially suggesting that Mary should start sleeping with her father-in-law – and that will really help the family. That’s incest and, of course, she is appalled. She also said that she had recently quarrelled with her brother, Surrey, on religious grounds because he had discouraged her from going too far in reading the scriptures, which suggests to me that she’d be reading them in English – and he’s not sure that is okay for women.

On the basis of this, some historians have said that for that reason they hated each other and that they were enemies and so on. I think that’s going too far. I think they’re both passionate characters and just because they quarrel sometimes, it doesn’t necessarily mean that that brother and sister hate one another.

Sarah:

Do you think that she believed at that stage that her brother would be executed? Or do you think she thought these charges wouldn’t stand or that they wouldn’t be as serious and that she could therefore get away with recounting some of these very honest conversations and he’d still be okay? And at the same time that perhaps she could help her father?

Nikki:

It’s really hard to say. To be questioned by the King’s counsellors is not a very pleasant experience. It’s difficult to keep your cool and not give them some kind of information under those conditions. Cynically, there are reasons for her to try and protect her father. She is still a single widow. She seems, by this point, not to be very well off, despite having won the jointure fight. She continually sells land through the 1540s. So if her father is executed, she would lose her source of financial support; she would lose the house and she might have to marry Thomas Seymour after all.

She does know which side of the bread is buttered. She is also questioned directly about her brother’s heraldry because they’re zeroing in on this. She responds in quite vague terms. She thought that he had more than seven rolls of arms and that he had resumed the Stafford arms of their grandfather and that the crown above them, in her judgement, looked like a close crown. That’s been taken as evidence of her complicity with the government in trying to destroy her father and brother. But it’s quite vague; saying that something looked so in her judgement, doesn’t say that it was so.

Sarah:

Yes, indeed.

Nikki:

Mary’s not daft, she’s a noblewoman. She knows about heraldry and she could have been a lot more specific if she wanted to be. So, I think she is trying to do her best to steer a course through this. She’s in a really difficult position and she recognises that she’s not going to be able to save them all because Surrey has done enough stupid things. None of her descriptions of things that Surrey said was used to convict him. They probably don’t help his case, but they don’t form part of the final trial. It’s not fair to say that she causes her brother’s execution, or that she’s trying to do so because there were also plenty of other depositions that do condemn him.

Sarah:

So her brother is executed; her father by the skin of his teeth gets away with it only by the death of Henry VIII. What happens next to her? How much longer did she live? What happens after this episode?

Nikki:

After this, she takes, custody, of her nieces and nephews; her brother’s children. She hires the reformer, John Foxe, as their tutor; something Norfolk would have hated. Actually, the first thing he does when he’s released in 1554 is to sack Foxe. I really wish I’d been a fly on the wall for that conversation! During this time she petitions the council saying, look, if you want me to look after these kids, you need to give me the money to do so.

She also petitions the council a lot on her father’s behalf. He recognises this later in his will saying, leave her some money because she tried so hard to help me. So she doesn’t just forget about him. The other thing she does through Edward’s reign is to really crack on with religious reform and with patronage in that regard. So, she has John Foxe, the famous martyrologist in her household; she’s also the patroness of John Bale, who is another reformist writer, and several others. She seems to work with the printer, John Day, to print reformist texts and get the word out to people who can read in English. Mary Howard is a big part of that reformist circle of noblewomen.

Sarah:

At the same time, she’s looking after her nieces and nephews. So, she’s in charge now of the future Duke of Norfolk, is that right?

Nikki:

Yes, absolutely. And some of her teaching, or Foxe’s teaching, does seem to go in and take root because it is clear that later on Thomas Howard, fourth Duke of Norfolk, is a Protestant. He is not Catholic like his father was. The Howards are often assumed to all be Catholic, and many of them are very strong Catholics – even to this day, the Dukes of Norfolk are still Catholic. It’s a strong part of their identity, but actually, during the Tudor period, it wasn’t quite as clear cut. Not everybody followed that same path. So, yes, she does seem to have encouraged the future fourth Duke of Norfolk to follow a reformist path.

The Death and Burial of Mary Howard

Sarah:

What about the end of Mary Howard? Where did she die? Do we know from what and where was she buried?

Nikki:

She dies at some point in, or before 1555, but probably in that year. We don’t know exactly where, and we don’t know exactly when. We only know she’s died because some of her lands start to be parcelled off to other people. She doesn’t leave a will, and that’s really unusual for a widow in her position. That suggests to me that her death was sudden or unexpected. It’s possible that she died in the influenza epidemic that raged during those years.

The historian, Barbara Harris, has said that the number of noblewomen who die in those middle 1550’s years is quite extraordinary and might suggest that they were hit pretty badly by that epidemic. We don’t know for certain. It’s a bit sad; though; Mary kind of fizzles out. This might also be because by 1555, Mary I is on the throne and, of course, for someone of reformist beliefs like our Mary, you would want to keep your head down during that time.

Sarah:

Her tomb is at Framlingham Church, where she apparently lies alongside the body Henry Fitzroy. Whether she’s actually in that tomb or not, we don’t really know, do we?

mage via Wikimedia Commons: Evelyn Simak / St Michael’s church in Framlingham – Henry Fitzroy tomb / CC BY-SA 2.0

Nikki:

No, it’s not certain but St Michael’s Church, Framlingham is usually given us her burial place, alongside her husband Henry Fitzroy.

Sarah:

So, if people are interested in following the footsteps of Mary Howard that’s one place to go and see. Are there any other places that are specifically associated with her or have they all been lost?

Nikki:

Unfortunately, most of them have been lost. You could go to Framlingham Castle; she would have spent time there, or to Hampton Court Palace, because she would certainly have spent time there as well. Because most of Henry’s palaces have been lost and sites like Kenninghall don’t really survive either, there isn’t a huge number of places that are directly associated with Mary.

Sarah:

Well, that’s is a shame but that was such a fascinating chat! I always really loved her and was intrigued by her, but now that we’ve spoken, I’m even more blown away by how interesting and formidable a character she was; as a woman of her time and as a force of nature.

Nikki:

Thanks for having me!