Stirling Castle: The Childhood Home of Mary, Queen of Scots

Stirling Castle was one of Scotland’s premier strongholds during the medieval period. It was also a place with a particularly bloody history. In my quest to follow in the footsteps of Mary, Queen of Scots, we must travel to this austere fortress, where we will explore a brief history of the building before looking at the development of the castle and going in search of the events that took place there, some of which were truly pivotal in the story of this beautiful, but ultimately ill-fated, queen.

A Brief and Bloody History of Stirling Castle

While we are going to focus on the history of Stirling Castle over a very brief window in time, namely circa 1542-1566, the well-documented history of this strategically important Scottish palace stretches deep into the early medieval period. The earliest references make mention of royal lands in the vicinity and a park is first recorded at some time between 1165 and 1174.

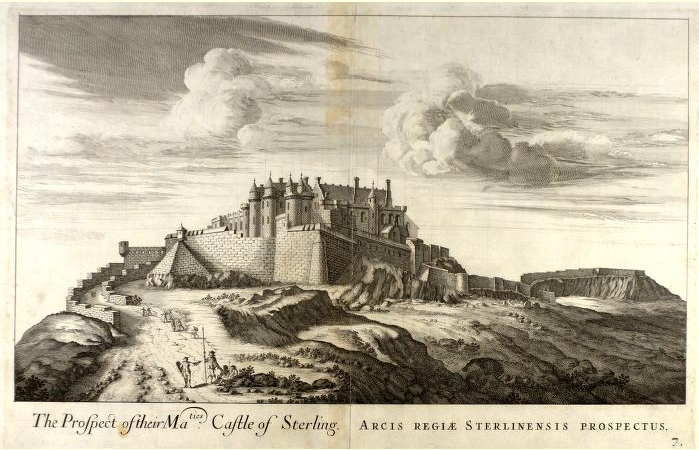

At the time, Stirling Castle was sited on the only main route connecting the Highlands with the Lowlands of Scotland, about 38 miles or so due north-west of Edinburgh, Scotland’s capital. It sat high up on a craggy hillside, virtually impregnable on three sides and commanding extensive vistas across the Scottish countryside. It also happened to dominate the only bridge crossing the mighty River Forth. All this made the castle of immense strategic importance. It was said that to hold Stirling Castle was to hold Scotland.

The English were well aware of this. Indeed, much of Stirling’s early history involves the castle being passed back and forth between English and Scottish ownership for roughly 200 years between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries. However, by the fifteenth-century, there was the gradual metamorphosis from fortress to pleasure palace as Stirling Castle became a favoured royal residence of the Stewart dynasty.

The Creation of a Royal Enclave at Stirling

Running in parallel with the development of Stirling Castle as a royal stronghold, came the development of its adjacent town. This was encouraged by the Crown, not only to stimulate the economy and trade but also to supply the royal court with essential provisions.

While the Scottish court was around one-third of the size of its English counterpart (around 350 during the reign of James V: 1512-1542), interestingly, even the grander royal residences, such as at Stirling, only had accommodation for the royal family and a select number of the highest-ranking aristocracy. This, in contrast to the ‘Greater Houses’ of Tudor England, such as Hampton Court, Whitehall, Richmond Palace, Greenwich, Eltham or Woodstock, where the entire court of around 1000 people could be housed at any one time.

As far as the Scottish court was concerned, therefore, this meant that the remainder of those listed as part of the ‘court’ had to take up lodgings in the town, such as Mar’s Wark. Harrison (see below for the link) describes how the physical arrangement of the castle and town mirrored the social status of those living in Stirling in the sixteenth-century, such that the monarch occupied the most prestigious position on the highest outcrop of land, the nobility close by, in the old town, and those of lesser means at the bottom of the long slope, upon which the town was built.

The Development of Stirling Castle

The castle is strongly defensive in appearance, not only on account of the steep, craggy cliffs that fall away from the castle walls on three sides but also because of the imposing walls, turrets and main gateway on the south side of the castle. This defensive stretch is recorded in early documents as the ‘forework’, (a name still used today). It was constructed on the orders of Mary’s grandfather, James IV (husband to Henry VIII’s sister, Margaret Tudor).

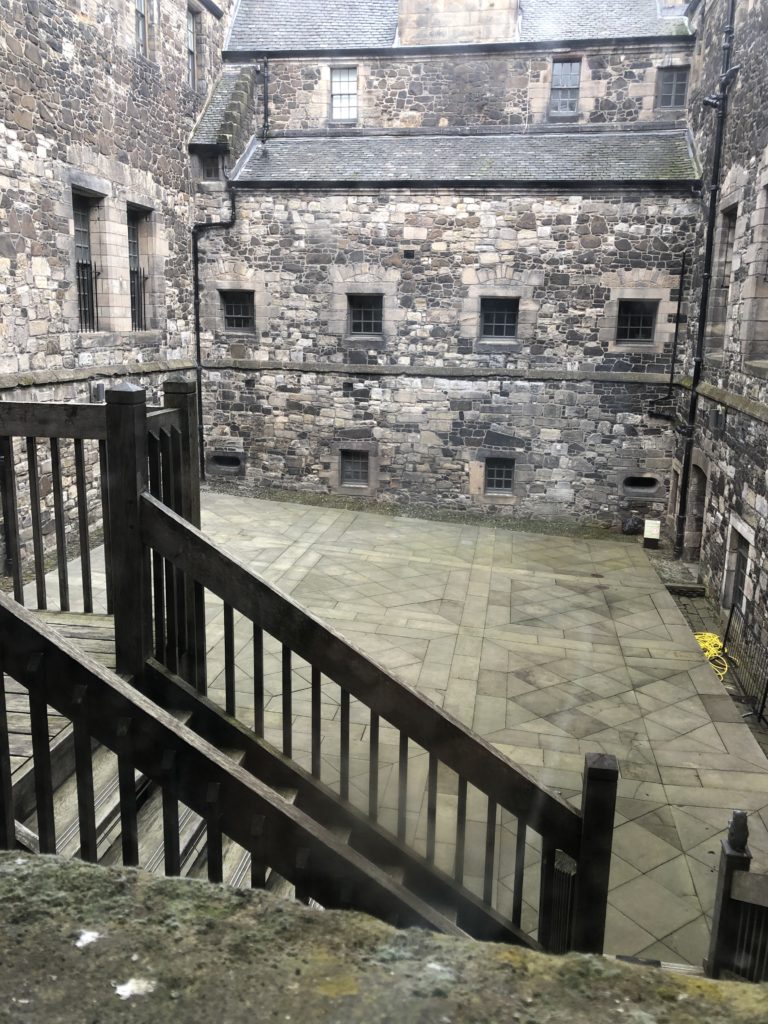

Alongside this work, James IV constructed a great hall, a chapel and a range of royal lodgings known as, unsurprisingly, ‘The King’s Lodgings’; these buildings were arranged in a rather lopsided ‘C’ shape around the east, north and west of a central courtyard called, the ‘Inner Close’. There are two things that I think are worthy of note.

Firstly, the Great Hall is described by John Dunbar as ‘probably the grandest secular building to have been erected during the later Middle Ages’ (in Scotland). There is certainly no extant comparator left in the country. Measuring about 38 m by 11m, it is ‘comparable in scale with all but the very largest great halls in England and the Continent’. Indeed, the main design elements were dawn from England and, most likely, from Eltham Palace, where a delegation from Scotland was received and entertained by King Henry VII in 1486.

It seems that delegation took note of what they saw at Eltham and ultimately aspects of the English hall were incorporated into James’ new, great hall at Stirling. If so, then the familiarity of Margaret’s childhood home must have been of comfort to the new Scottish Queen, who arrived in Scotland around the time of its completion at the turn of the sixteenth-century.

The other thing to note at Stirling Castle is that the chapel in which Mary, Queen of Scots was crowned on 9 September 1543, is not the chapel which stands today. This older chapel was destroyed and rebuilt in the late sixteenth-century, slightly to the north of the original. Sadly, the only details that remain of how that chapel looked were that it may well have been aisled and possibly had a south-facing entrance porch.

The coronation ceremony that took place at Stirling in 1543 was witnessed by the English Ambassador to Scotland, Ralph Sadler (who, incidentally, was a Thomas Cromwell protégé; in his earlier years, he was Cromwell’s secretary with rooms at Thomas’ grand, London home at Austin Friars). Sadler described the coronation as having ‘such solemnity as they do use in this country, which is not very costly.’ Clearly, he wasn’t much impressed!

The Royal Palace at Stirling Castle

Having founded the Chapel Royal at Stirling Castle in 1501, Mary’s grandfather, James IV, celebrated Easter at the castle every year. Mary’s father, James V, spent even more of his time there. Around 40% in total. So, perhaps it is no surprise that when his widow, Marie de Guise, wanted to retreat to the most secure fortress in the land during Henry VIII’s ‘rough wooing’ of her infant daughter, she headed to Stirling for protection.

Mary was conveyed from the place of her birth, Linlithgow Palace to Stirling Castle on 27 July 1542, escorted by an armed guard of 3500 men. She was crowned six weeks later and would spend the next four years at the castle. And so, as mentioned at the outset of this blog, Stirling Castle became what one might effectively call Mary, Queen of Scots’ childhood home.

But what do we know of the royal apartments? Well, one of the beauties of visiting the locations associated with Mary, Queen of Scots today is that many of the principal locations associated with her life still stand, including the royal apartments at Stirling Castle.

These lodgings, which henceforth became known as ‘the palace’ or ‘palace block’, made up four ranges centred on a small internal courtyard known as, ‘The Lion’s Den’. Two sets of lodgings, each comprising of three principle chambers, (in addition to two or three smaller ‘closets’), made up the king and queen’s side. During Mary’s time, I am assuming that the little queen occupied one side and her mother, Marie de Guise, the other.

In Scotland, the suite of rooms accorded to the monarch was given the term ‘chamber’. Thus, confusingly, the royal ‘chamber’ may donate a set of rooms, or indeed a single room within the suite. Although the nomenclature was a bit different, this arrangement shared quite a number of similarities with the arrangement of rooms in any aristocratic house on the other side of the border. However, it is probably fair to say that the number of rooms in a Scottish royal chamber tended to be less than at the great palaces of Tudor England.

Both sets of chambers at Stirling Castle were accessed via a stairway from the Inner Close, at the western end of the block. The stairway, in turn, opened onto a corridor, or gallery, which led to the main entrances of each royal ‘side’. Once inside the king or queen’s ‘chamber’, you would progress through a series of rooms. These were increasingly private and intimate. We will look at each of these in turn.

The first of these was the outer ‘hall’, which was used for more public events and receptions. Such was the case of the wedding feast of James IV and Margaret Tudor, where we have an eyewitness account of the nuptial celebrations taking place in the royal chambers. Although this account describes events at Holyrood, it nevertheless provides an insight into how these royal chambers were used and decorated. Our eye-witness is John Young. He notes the king dining in the ‘king’s hall’ on his wedding day, alongside the Scottish party. The room was lit by six large beeswax candles and was decorated with tapestries and ‘a rich dresser for the display of plate’.

The next room in the sequence was the Outer, or Great, Chamber. This too was a public chamber, accessible to anyone with reasonable status at court. It was a room used to greet honoured guests, dine and enjoy entertainments, such as dancing or watching a play. Once again, tapestries decorated the walls. At the high end, closest to the next chamber in the sequence, was the king or queen’s throne sited beneath a canopy of state. Indeed, on the morning of James’ wedding to Margaret Tudor, the king received the Archbishop of York and the Earl of Surrey in his Great Chamber at Holyrood.

Beyond this, we move into the privy chambers, where access was strictly controlled. The next room in the sequence was termed the ‘second’ or ‘inner’ chamber. This acted primarily as a private, but social, space. It often contained a bed of state; a symbol of regal power. However, more often than not, the king or queen would sleep in a smaller, more portable bed, found in one of the two or three smaller, most intimate rooms (closets) associated with each ‘chamber’.

Although some 100 years before Mary’s time, it is believed that it was in the King’s Inner Chamber at Stirling Castle (not in the current palace block but in an earlier building at the castle) that James II summoned, then brutally murdered, the Earl of Douglas. Aided by courtiers who were dining with the king, when Douglas refused to accede to the king’s request, James lost his temper and stabbed Douglas in the neck 29 times before his body was thrown from the nearby window. Charming! The room is still known today as ‘The Douglas Room’.

Finally, we move into the inner sanctum of the royal lodgings: the closet. These small rooms, of which there were three on the king’s side and three on the queen’s at Stirling (now lost), were private spaces often reserved for personal devotions. Therefore at least one of the closets was invariably furnished with an altar, plate and vestments.

Mary Returns to Stirling Castle

Mary would not return to Scotland until August 1561. She was nineteen years old and already a widow. The Scottish Queen spent a month at Stirling Castle the following year, in the summer of 1562, and was there for most of September, October and November 1563. By her visit in the Spring of 1565 (April and May), Mary’s was fate was already set on a different – and dangerous – course.

At Wemyss Castle in early February, Mary had become reacquainted with a young man she had first been introduced to during her time in France, a certain Henry, Lord Darnley. From late February, the ‘yon long lad’ (as Elizabeth I called him) was constantly by her side. Two months or so later, when the royal court was at Stirling during the spring of 1565, Darnley fell ill with the measles. Mary personally insisted on nursing him back to health, a sign surely that she had already, fallen for the charms.

After Darnley recovered, he was created Lord of Ardmanoch and Earl of Ross at Stirling Castle on 15 May 1565. Mary married him two months later at Holyrood, in Edinburgh. It was a deeply unpopular match on both sides of the border. Although the forces that ultimately saw the Scot’s Queen cast out of her kingdom were complex, it was, perhaps, at this point that we can say that Mary’s fate took a sinister turn for the worst.

Mary, Queen of Scots would return to Stirling Castle twice more in September and December of 1566. At the time, her infant son was lodged there in the care of John Erskine, Earl of Mar. Whether she knew it or not, Mary’s life was beginning to hurtle headlong towards a catastrophic outcome. It must have been in the royal chamber at Stirling castle that she kissed her son goodbye for the final time. They would never meet again.

Gallery

Here are some additional images of Stirling Castle for you to enjoy…

All the above gallery images are the author’s own.

Sources

Sources I have found useful in writing this blog are:

THE ROYAL COURT AND THE COMMUNITY OF STIRLING TO 1603

John G. Harrison, p 29.

Scottish Royal palaces: The Architecture of Royal Palaces During the Late Medieval and early Renaissance Periods, by John G. Dunbar.

The State Papers and Letters of Sir Ralph Sadler

The Marie Stuart Society : Stirling Castle

Also:

Visitor information for Stirling Castle can be found here. Note that in recent times, a major refurbishment of some of the royal chambers has taken place at the castle. This allows the visitor to see the sumptuous and colourful chambers as they would have been known by the likes of Mary, Queen of Scots. We are indebted to Stuart Interiors, who completed the refurb for allowing us to use some of their images in this blog.

To visit Mar’s Wark in the town of Stirling, check out this site.

Hi! It’s Olivia, I met you today at Basing House! Thank you for recommending your website and blog to me, it looks fantastic and I can’t wait to explore it in more depth! It’s the perfect place for me and my mum to help plan our Tudor road trip! Thank you for working so hard on this, it’s wonderful!! So great to find a kindred soul with the same love and excitement for tudor history!

Hi Olivia! Yes hello! Great to see that you found me. I am delighted to have you as part of the community. there will be loads for you to explore here and on podbean (podcast) and my YouTube channel – and the guides and In the Footsteps books will be perfect for trip planning. Let me know how you get on. : ) Best wishes, Sarah

Salut’, I would like more information on, how to book a trip from, Alaska please? I love the research.I have been discovering my History from Scotland and I’d like, very much, to witness my Ancestry, up close and personal. Thank you for your consideration.

Sincerely, Alisa V. Stuart

#SEMPER EADEM#

Hello Alisa! Thanks for your question. I’d look into flying directly into Scotland – Glasgow or Edinburgh. If not, Heathrow or Gatwick and a connecting flight to the aforementioned airports. Then you might want to look up Anne Daly, who does some wonderful tours helping people find their Scottish ancestry. If you do make contact with Anne, can you mention that I referred you to her? I don’t get anything from it but it would be lovely if she knew I was thinking of her. I hope you have a great trip!