Cawood: A Cardinal’s Lamentable Treason

As the deepening chill of late autumn crept icily across the Yorkshire countryside, a cavalcade of men on horseback, headed by the twenty-eight-year-old, Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, swept into the gates of Cawood Castle. Inside, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, one-time chief minister to Henry VIII, was at dinner, entirely unaware of the storm that was about to sweep him up and crush him. It was the beginning of the end for Wolsey.

November 1530, saw the dramatic arrest of Cardinal Wolsey at Cawood, North Yorkshire. It was the first step on a journey that would end, just over three weeks later, with the Cardinal’s broken body being lowered into its shallow grave at Leicester Abbey. To commemorate these climactic events, through this month we shall be following the Cardinal’s progress, drawing upon an amazing first-hand account written by his gentleman usher, George Cavendish.

As gentleman usher, George’s role was to ‘keep the door’ of whichever chamber Wolsey was using at the time. Therefore, he had close and personal access to Wolsey and, thankfully for us, was privy to the most intimate conversations and events, involving the Cardinal, during those final few weeks of his life. It is a rare and valuable account and one that contains astonishing detail, allowing the reader to open a portal in time and relive the sorry tale of a once-great statesman shattered by the hatred of his enemies.

The History and Site of Cawood and its Castle

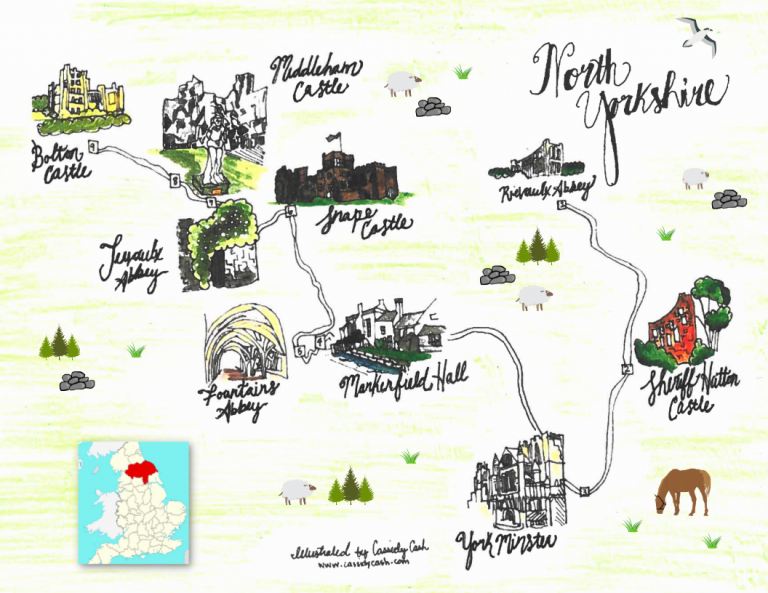

Today, Cawood [correctly pronounced Cowud] Castle is but a willowy shadow of the once great archiepiscopal palace that, at its zenith, was described as ‘the veritable Windsor of the north’. Lying just seven miles south of the City of York, and on the navigable banks of the River Ouse, its foundation can be traced to the year 930, when the Saxon King, Athelstan, granted land at Cawood to the diocese of the aforementioned city. Subsequently, the fortunes of the manor house [later called castle] at Cawood waxed and waned, ‘first as a simple residence of the Archbishop, and then as an almost impregnable fortress,’ with the property being built up at various times, before apparently falling into decay; a cycle which seems to have repeated itself through Cawood’s illustrious history.

But what of the village of Cawood and its palace? What do we know of how both appeared to the sixteenth-century traveller? John Leyland’s Itinerary provides a short, but contemporary, account of the surroundings of Cawood Castle, stating that: ‘After another four miles, where the soil was good for pasture, corn and woodland, I crossed the river and arrived at Cawood. The Archbishop of York has a very fine castle here.‘

In Blood and Taylor’s, Cawood: an Archiepiscopal Landscape, we hear that: ‘The palace was clearly meant to be approached from the south corner of the village market place across the Bishop’s Dike, presumably by a bridge, alongside an assumed continuation of the gatehouse range and then left through the gatehouse into the palace proper.‘ We will hear more of this range later…

It is this gatehouse, and its range, that are the only substantial remains of the archepiscopal palace. Sadly, no floor plans or contemporary drawings of the palace survive from the medieval period, nor do any detailed descriptions of the palace buildings themselves. Thus, we simply do not know exactly how Cawood appeared during Wolsey’s stay there. However, all is not lost! From the surviving buildings, an eighteenth-century etching, and a number of key documents, including Cavendish’s account, we can build up a reasonable picture of the palatial residence that witnessed these electrifying events.

Re-imagining Cawood Castle

According to Alastair Oswald, Landscape Archaeologist at the University of York, who has studied Cawood Castle and its environs, ‘in Henry’s [VIII] time, the palace almost certainly comprised two square courts back to back’. This dual courtyard arrangement was, of course, typical of fashionable, high-status houses of the day. Knowing this, we can predict with a degree of certainty how the chambers of the palace were arranged.

Oswald postulates that: ‘The building known [today] as the Banqueting House [confusingly it is actually the gatehouse range, referred to above] occupied the front range of the outer court and therefore probably provided stabling and accommodation. The real dining hall would have occupied the range between the two courts. A chapel would have stood on one side of the inner court and the Archbishop’s private accommodation (which he would, of course, have surrendered to any royal visitor), would have occupied the rear side of the inner court, or perhaps the eastern side, looking towards the gardens, the village church, and would have had an oblique view of the river unspoiled by any ungodly activities on the wharf.

In so far as the chambers within the castle are concerned, two inventories, compiled toward the end of the castle’s life, help us to further re-imagine its original appearance. The first is a report compiled for Thomas Cromwell in relation to ‘the visitation of the Province of York on 12 Jan 1536’. Recorded in the Letters and Papers of Henry VIII, the report states that Cawood consisted of:

‘…the hall, pantry, buttery, ewery, great kitchen, &c., porter’s lodge, gatehouse chamber, upper chamber over the gatehouse [both still extant], and in all the different chambers, including the treasurer’s chamber, Dr. Bonar’s chamber, Constable’s chamber, my lord’s sleeping chamber, the great chamber, the chapel, the lodging of bishop Savage, the little gallery towards the water side, the library, Mr. Winter’s chamber, the chamber in the tower, and Augustine’s chamber; in all 49 chambers or apartments.‘

With all this information to hand, we are ready to bring some of these chambers to life, as we are drawn back in time to pick up our story of the Cardinal.

Wolsey’s Arrest: Friday, 4 November 1530

Wolsey had arrived at Cawood Castle towards the end of September 1529. A little over one year later (just days before he was due to be consecrated as Archbishop of York), on 4 November 1530, Henry Percy and Walter Walsh (a groom of the King’s Privy Chamber), arrived to arrest the Cardinal. Wolsey was at dinner in his chambers on the first floor. We can assume this was mid-morning, between 10.00 – 11.00 am. This was when the Tudors customarily had their main meal of the day.

Northumberland’s first task was to secure the castle, commanding the porter to surrender the keys to the gates but who would, initially, ‘in no wise deliver’ them to the Earl. Percy also blocked passage from the principal stairs going up from the great hall to Wolsey’s privy suite, so that ‘no man could pass up again that that was come down’.

In this way, for some time, the Cardinal and certain members of his household remained oblivious to the commotion going on in the great hall below until, as Cavendish reports, ‘At last, one of my lord’s servants chanced to look down into the hall … and returned to my Lord, and showed him that my Lord of Northumberland was in the hall.

It is clear from Wolsey’s reaction to hearing of his visitors that the Cardinal was clueless of the real and sinister nature of Percy’s visit. Remember, Percy had once been a junior member of the Cardinal’s household before he had inherited his patrimony. So, the two men knew each other well, with Thomas referring to Henry Percy as his ‘very old and loving friend‘.

Rising from his table, Wolsey made to greet his guest, encountering the Earl midway up the staircase with ‘all his men about him‘. Their greeting was warm and congenial, Wolsey, ‘taking the earl by the hand and leading him up to the chamber‘. But what was this chamber?

We know from a seating plan of a medieval event, which was held at Cawood in 1465 (and which came to be known as the Great Feast of Cawood), that diners were accommodated in one of five locations: the great hall, the chief chamber, the second chamber, the low hall and the gallery. It is likely that the great hall, which we have already encountered on the ground floor, led up to the ‘chief’ chamber (perhaps the great watching chamber) with, in all likelihood, the second chamber lying beyond that. In accordance with what we know of the layout of great Tudor houses of the day, perhaps this was Wolsey’s Presence Chamber. I suspect that in one of these rooms, the remains of Wolsey’s dinner was still laid out.

From Cavendish’s account, it was clear that Thomas Wolsey was keen to show hospitality to his guests – and for them to be provided with food and accommodation. The Cardinal offered Henry Percy his bedchamber so that the Earl might change out of his riding attire. He also commended Percy for doing as Wolsey himself had once taught him in his youth, to ‘cherish your father’s old servants‘.

Leading the Earl into his nearby bedchamber, Cavendish took up his usual position by the door and was the only one (as he reports) to hear what happened next. Standing at a window by the chimney, the Earl, ‘trembling, said with a very faint and soft voice…”My Lord, I arrest you of high treason“. Cavendish watched as the two men stood in silence, with Wolsey ‘marvellously astonished‘. Wolsey demanded to see the commission for his arrest, sent by the King. He would bow to no other as he told the Earl that he feared that ‘an ancient grudge‘ between some of ‘your predecessors and mine‘ might lie behind this abrupt turn of events.

For Wolsey knew he had mortal enemies: The Dukes of Norfolk and Suffolk amongst them – and, of course, Anne Boleyn herself. In fact, in this account is the Cardinal referring to the incident in which he forced Henry Percy to give up his betrothal to Anne Boleyn, who thereafter swore that she would one day bring down the Cardinal if it were in her power to do so? Maybe. However, the drama of that morning was not over.

Cavendish’s attention was caught next by Master Walsh’s voice. Whilst Percy had been busy with Wolsey, Walsh had apparently apprehended the Cardinal’s Venetian physician, Dr Augustine. With the words, ‘Go in thou traitor, or I shall make thee‘, a bewildered and petrified Dr Augustine was ‘thrust‘ through the doorway ‘with violence‘. Astonished by these events, Cavendish then watched a more civilised Walsh kneel before the Cardinal. While he too refused to show Wolsey the commission which gave them the authority to arrest him for treason, the Cardinal willingly yielded to this second gentlemen. As a Gentleman of the King’s Privy Chamber, he himself was ‘sufficient commission‘ and pledged thereafter to ‘obey the king’s will and pleasure‘ but that, he added, ‘he had never offended the King’s Majesty in word or deed.’

All haste was made for their departure. While Wolsey’s cavalcade did not set off on its winding journey to London until the Sunday, Doctor Augustine was conveyed the next day ‘with as much speed as they could, his feet tied under the horse’s belly‘. On Sunday morning, Wolsey’s household was allowed to come before him in the Great Chamber, ‘among whom there was not one dry eye, but all pitifully lamented their master’s fall and trouble‘. The Cardinal thanked those who had served him diligently, declared his innocence and shook each by the hand before, heading downstairs, out through the great hall (I imagine) and into the inner courtyard, there to mount his mule.

As the great gates of Cawood were swung open to allow the party on its way, Wolsey came face-to-face with around 3000 well-wishers who cried out, ‘God Save Your Grace. God Save your Grace. The foul evil take all them that have thus taken you from us! We pray God that a very vengeance may light upon them!’ And so, says Cavendish, as the Cardinal was taken on his way, to what fate he knew not but might well guess, the crowds ran behind him through the town, ‘they loved him so well‘…

In two week’s time, the story continues as we journey alongside Thomas Wolsey on his way towards London. We shall lodge at Sheffield Park, home of the Earl of Shrewsbury, and hear how Wolsey became dangerously unwell with the final illness that would take him to his grave at Leicester Abbey. In the meantime, if you wish to read an earlier post about Wolsey’s fall from grace and his refuge at Esher Palace in Surrey, click here.

If you wish to stay at Cawood Castle, you can book through the Landmark Trust. Click here for further details.

Sources:

Sources I have found useful in writing this blog are:

The Life of Wolsey, by George Cavendish

The Letters and Papers of Henry VIII

John Leland’s, Itinerary.

Blood and Taylor’s, Cawood: an Archiepiscopal Landscape.

Personal Correspondence with Alastair Oswald, the University of York.

6 Comments