The Old Palace of Hatfield: The Cradle of the Elizabethan Age

The Old Palace of Hatfield was one of the most significant places in the life of Elizabeth I. It was to Hatfield that the 3-month-old princess was brought from London to establish her first household under the watchful eye of Sir John and Lady Shelton, the uncle and aunt of Anne Boleyn. Some twenty-five years later, while sitting under the gnarled oak tree in the Great Park at Hatfield, Princess Elizabeth heard of the death of her sister, Mary and, therefore, of her accession to the throne of England. There had been difficult and dark times, but the age of Gloriana was about to dawn.

It had been a long, tortuous and perilous road from heiress, then bastard, to suspected traitor before eventually finding some semblance of safety by inheriting her birthright as Queen of England. Through this time, the Old Palace at Hatfield was a place Elizabeth retreated to, fought for, and called home. So many events unfolded there that the Old Palace is one of the most important sites to visit on any Tudor-lover’s road trip, particularly for those who admire Elizabeth. While the grand Prodigy house, which dominates Hatfield Park today, is the main attraction for many visitors, we will focus our attention on the earlier royal Tudor palace.

The Origins of the Old Palace at Hatfield

The original manor house at Hatfield was owned by the Bishops of Ely and was sited some half a mile from the current Hatfield House, north of the park. However, by the end of the fifteenth century, when the Battle of Bosworth was being contested between the Houses of York and Lancaster, the then Bishop, John Morton, built himself a new episcopal palace adjacent to the parish church. The new building would stand prominently on a spur of high forest land overlooking the earlier-cleared and cultivated valleys that surrounded the tiny medieval hamlet of Hatfield.

The location of the palace was critical to the site of its construction. It lay just east of the old Great North Road (a main medieval highway leading north from London). Being within a day’s ride of the capital, it was a convenient stopping-off point for the medieval bishops, who regularly travelled to and from London as business dictated. (See also Buckden Palace for a similar arrangement).

Approaching the Old Palace at Hatfield

Access to the palace was via a gatehouse, sited at the top of Hatfield’s main street, which ran through the centre of the village. This was, and still is, known as Fore Street. The development of Hatfield’s new town in the twentieth century meant that the old town was mainly left unmolested by over-enthusiastic developers. Therefore, thankfully, it retains something of its olde-worlde village feel.

If you visit today, I highly recommend you ignore the main signs leading you to ‘Hatfield House’ and instead plug ‘Old Hatfield’ into your sat nav. Find a place to park at the bottom of Fore Street, then walk uphill towards the original main entrance.

Imagine the cavalcade bringing the infant Princess of England to her new home. Of course, it was not only Elizabeth who passed this way. Henry VIII visited on many occasions, particularly from 1514, when he began to use it as if it were already his home – although in truth he would not acquire it formally from the Bisophric of Ely until 1538. One early twentieth-century author asserts that from 1524, it seems to have been used as a royal palace. As we shall hear, Anne Boleyn visited her daughter at Hatfield and Princess Mary was sent there in disgrace to attend upon her baby sister. As ever, when Mary and Anne were near one another, fireworks invariably ensued! More on this later.

In the early sixteenth century, Fore Street was also a marketplace. Various shops fronted onto the roadway. Gwendoline Cecil’s account of Hatfield’s appearance in the late fifteenth century mentions ‘eleven shops and one or two houses of apparently some importance’. She states there were leather makers, ‘butchers, bakers, fishmongers, brewers, and last but not least, ale sellers’, or keepers of ‘tippling houses’ as they were apparently called; twenty-six of these ale sellers are recorded. As Gwendoline notes, for such a small population, this number of alehouses suggests a sizable consumption of beer!

At the top of Fore Street are the original entrance range and gatehouse; the parish church of St Etheldreda’s lies to the right-hand side of the road. If you are visiting, you will want to pause here a moment. Mary Tudor, sister to Henry VIII, gave birth to her daughter, Frances, at the Bishops’ Palace between 2.00 and 3.00 a.m. on 16 July 1517. Two days later, the infant was christened at the parish church. We have been left with the most splendid account of that christening! As you take a moment to explore the church, why not take this description with you:

‘The road to the church was strewed with rushes; the church porch hung with rich cloth of gold and needlework; the church with arras of the history of Holofernes and Hercules; the chancel, with arras of silk and gold; and the altar with rich cloth of tissue, and covered with images, relics, and jewels. In the said chancel were, as deputies for the Queen and Princess, Lady Boleyn and Lady Elizabeth Grey. The Abbot of St. Alban’s was godfather. The font was hung with a canopy of crimson satin, powdered with roses, half red and half white, with the sun shining, and fleur de lis gold, and the French Queen’s arms in four places, all of needlework. On the way to church were eighty torches borne by yeomen, and eight by gentlemen. ‘

It is postulated that ‘Lady Boleyn’ was almost certainly Anne Boleyn’s mother, Elizabeth.

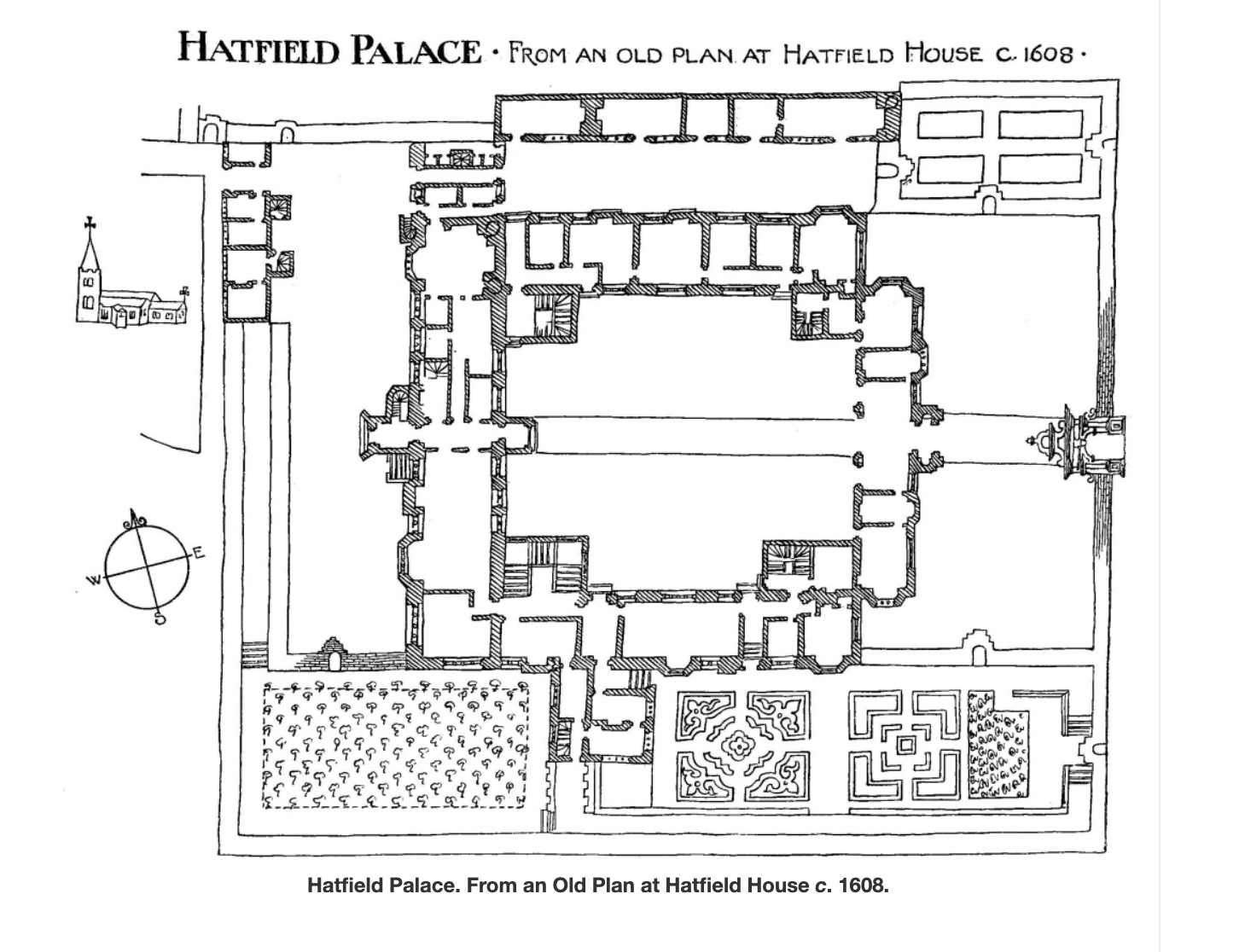

Professor Anthony Emery, in his Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, believes that it was this gatehouse which was the original entrance to the palace and that the later main entrance, shown on the east of a plan of the palace dated 1607, was either ‘a later Tudor development associated with the construction of the three lost ranges’, or perhaps was changed around after the house was acquired in 1607 by Robert Cecil, first Earl of Salisbury and Chief Minister to King James I. He is known to have created a new road from the south, which may have then used this new, easterly entrance.

Beyond the gatehouse next to the church (shown in the diagram above) is a ‘Victorian-ised’ courtyard; on the far side, however, the original west range of the Old Palace fills its entire length (120 feet by 37 feet). This is believed to have comprised the great hall, or Banqueting Hall, to the south, separated by a typical screen’s passage from other service offices and kitchens in the northern part of the range.

While the great hall was open to the roof, the northern part of the range was separated into two floors with, as Emergy calls it, an ‘important apartment’ reached from the newel stair built into the side of the main western porch. In the Banqueting Hall, the original bay window and fireplace shown on the plan have been lost. Still, the continuous fine, chestnut and oak roof of 11 bays shows how this building was initially constructed as one and then subsequently divided up for use.

There are a few events of note associated with the Banqueting Hall in the Old Palace at Hatfield. Just two years before her accession, when Elizabeth was 22 years old, she enjoyed:

‘…a great and rich masking in the Great Hall at Hatfield where the pageants were marvellously furnished. There were twelve minstrels antickly disguised with forty-six or more gentlemen and ladies, many of them knights or nobles and ladies of honour, apparelled in crimson satin embroidered uppon with wreaths of gold and garnished with borders of hanging pearl, and the devise of a castle of cloth of gold set with pomegranates about the battlements … At night the cupboard in the hall was of twelve stages namely furnished with a garnish of gold and silver vessels and a banket of seventy dishes a void of spices and subtleties with thirty spice plates.’

Of course, in 1558, she held her first Privy Council there on 21 November, just four days after her accession. During that meeting, she appointed William Cecil as Secretary of State. It was Cecil’s son who exchanged the principal family home of Theobalds, in Essex, with the then King James I, in 1607. As a result, the Cecil family are the current owners of Hatfield House, as they have been for the last 400 years.

The hall’s south end (high end) led through into an antechamber, with a flight of stairs leading up to the first floor, giving access to a ‘principal’ room. From this point forward, the appearance of the early Tudor house is unclear. The surviving plan shows a second courtyard to the east, embraced by four ranges; the western range is already described, but with additional ranges to the east, north and south.

There is a debate about whether these ranges were added later in the Tudor period, perhaps after Henry VIII acquired the house as a residence for his children from the Bishop of Ely in 1538, or whether this was a plan that was considered by Cecil when he came into possession of the palace in 1607, but which was never realised; the 1st Earl of Salisbury instead favouring the construction of an entirely new property, which today stands roughly where the gardens are shown to the south of the eastern courtyard.

Emery favours the former. In this case, the main western range probably had both north and south ranges of unknown size attached. These were probably extended, and an additional eastern range was added to complete the courtyard. This increased the size and grandeur of the house, making it fit for a royal household. Today, visiting the present-day Old Palace Garden reveals traces of the demolished wings.

The state apartments, where Elizabeth would have lodged during her stays at Hatfield, were likely to have been in the now lost south wing overlooking formal gardens – and were probably sited at first-floor level. Simon Thurley postulates that when the Lady Mary was sent to attend on her sister in 1533, she would have been accommodated either on the ground floor, below her half-sister’s rooms, or in the guest lodgings in the north range. It was in those lodgings that many tears were shed, and because of her stubbornness, Mary was ultimately forced to eat her meals in the great hall with the rest of the household – a great indignity for such a proud young woman of royal blood.

Hatfield: Elizabeth’s Refuge

So what more of Elizabeth’s association with the house? As we have said already, the Princess was first sent to live at Hatfield in December 1533. It would be the beginning of a regular circuit, with the princess’s household moving periodically between the royal manors and palaces of Hunsdon, Hatfield, Hertford, the More, Richmond, Greenwich and Eltham. The household was befitting her status as Princess of Wales and managed by a staff of nurses, courtiers and tutors.

On her first visit, Elizabeth remained at Hatfield until the end of March 1534, when she was moved to her father’s childhood home of Eltham, near Greenwich. During this time, the antagonism between Elizabeth’s mother, Anne Boleyn, and the Lady Mary came to a head. The two would clash in a titanic battle of wills at Eltham, but before then, Mary would unleash her disdain and hatred towards the woman who she must have thought had ruined her life

With the new Act of Succession ratified in Parliament during the same month, Mary was now very clearly the king’s illegitimate daughter. Her princely household had been dissolved, and as punishment for refusing to accept her father’s will, she had been sent to serve in her half-sister’s household at Hatfield. Anne tried to extend the olive branch of peace to the wilful 17-year-old during her visit. As we hear from Ambassador Chapuys, who was well-informed about the events unfolding in the Lady Mary’s life:

‘When the King’s “amye” [amie = ‘friend’?] went lately to visit her daughter, she urgently solicited the Princess to visit her and honor her as queen, saying that it would be a means of reconciliation with the King, and she herself (ladite amitie) would intercede with him for her, and she should be as well or better treated than ever.’

Eustace Chapuys, 7 March 1534

Lodged somewhere else in the palace, Mary was having none of it! Following the defiant lead shown by her mother, Katherine of Aragon, she stated that she knew no queen but her mother. However, she would be grateful if ‘Madame Anne de Bolans’ would intercede with her father on her behalf. According to Chapuys, ‘The Lady repeated her remonstrances and offers, and in the end, threatened her, but could not move the Princess. The other [Anne Boleyn] was very indignant and intended to bring down the pride of this unbridled Spanish blood, as she said, ‘She will do the worst she can.’

Three years later, Anne was dead, and the young Princess Elizabeth was herself declared illegitimate. Although she came and went, Hatfield remained a constant in Elizabeth’s life. She returned there in 1548, shortly after the embarrassing – and highly inappropriate – romps with Thomas Seymour, which had resulted in her being sent away from the Seymour household at Sudeley. If the 15-year-old hoped that the whole sorry affair would be brushed under the carpet, she was to be mistaken.

Thomas Seymour, who had been like a father figure to her, was arrested under suspicion of treason and of having been involved in a secret matrimonial plot to marry Princess Elizabeth. Elizabeth was at the Old Palace of Hatfield when the affair blew up, with Lord Protector Somerset sending Sir Robert Tyrwhitt to extract a confession from the 15-year-old. At the same time, her beloved cofferer, Thomas Parry, and Governess, Kat Ashley, were taken to London for questioning. Unpicking the whole affair is beyond the scope of this post. If you want to read a complete account of the scandal, you may do so here.

Suffice to say; it was in her rooms at Hatfield that Elizabeth had her first terrifying brush with accusations of treason; the daily questioning by Sir Robert, the pressure to confess, the worry about her friends and what others might say to implicate her under duress, was a sharp lesson in the dangers of being close to the throne. However, Elizabeth’s intellect steered a course through the fire, but the heat of those two intense weeks at Hatfield would shape her forever. According to Elizabeth’s biographer, Alison Plowden, ‘she had changed from a girl into a woman, and for better or worse, she would never be the same again’.

On her 17th birthday, Elizabeth finally acquired the manor of Hatfield outright. However, she had to petition the king, her brother, not to sell it to the Earl of Warwick, which was Edward’s intention. Clearly, Elizabeth loved the palace and considered it home – and a home worth fighting for!

Throughout her brother’s reign, Elizabeth lived mostly at Hatfield, with the occasional visit to Ashridge. Indeed, she was in residence through the accession crisis leading up to and following her brother’s death on 6 July 1553. When summoned by John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland and Head of the Royal Council, to Greenwich, Elizabeth did what any sensible Tudor princess would do – take to her bed declaring that she was far too ill to travel. A battle for the throne was about to sweep across southern England. Elizabeth wisely kept her head beneath the parapet as her half-sister went head-to-head with the new regime. Of course, it all went badly for Northumberland, who took down his son, Lady Jane Grey and her father while pursuing his ambition.

Life was tricky during the five-year reign of her sister, Mary. Now, the focus of Protestant plots to unseat the Catholic queen, Elizabeth, fell again under suspicion. After a spell in the Tower, where she was subject to intense interrogation and then placed under house arrest at Woodstock, Elizabeth eventually regained the queen’s trust. She was at least trusted enough to return to Hatfield in the autumn of 1555. From this point forward, Elizabeth visited the court in London occasionally. Although there always must have been some uneasiness between the sisters, life settled down, with Elizabeth enjoying hunting and walking in the park – and it was while at Hatfield that she began a correspondence and lifelong relationship with William Cecil.

Mary even visited Elizabeth at Hatfield in April 1557. Extensive preparations were made for her coming. We hear of the ‘great chamber’ being arranged for the queen. It was decorated with a fabulous set of tapestries depicting the Siege of Antioch. One morning after mass, Elizabeth entertained her half-sister with bear-baiting (perhaps in the courtyard) with which their highnesses, it is said, were ‘right well content’. The evening’s entertainment was a little more civilised by our tastes, involving the ‘acting and reciting by the choir boys of St. Paul’s’. We also hear Elizabeth playing on the virginals accompanied by one of the choristers.

The waiting was nearly over; Elizabeth had lived a privileged but dangerous life, navigating conflict, scandal and accusations of treason, all played out within the walls of the Old Palace of Hatfield. There was only one thing left to experience: triumph. On 17 November 1558, the 25-year-old princess must have been waiting anxiously at the palace, only too aware that her sister’s health was fast declining. When Mary’s ring was brought to her as a clear sign that the reigning monarch had died, Elizabeth’s heart must have burst from her chest. Falling to her knees from sheer relief, tears must have stung at her eyes as she famously declared, “0 Domine factum est illud et est mirabile in oculis nostris.” “It is the Lord’s doing, and it is marvellous in our eyes.”

Several days later, Elizabeth left for London to be crowned as the new queen, and those who had loved and supported her were at her side. Hatfield had held her safe through some of the happiest and the darkest times in her young life, and the lessons she had learned there prepared her well for the task ahead. Elizabeth would return to the Old Palace of Hatfield on many occasions throughout the rest of her life, and indeed, we might say that this place was the cradle of the Elizabethan age.

Sources:

I have found to be helpful in researching this blog:

In the Footsteps of Anne Boleyn, by S. Morris and N. Grueninger

Hatfield as it was 500 Years Ago, by G. Cecil. First published in the Bishops Hatfield Parish Magazine (May-June) 1904.

The Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, by A. Emery

Houses of Power, by S. Thurley

Elizabeth I, by A. Plowden

Some Notes on Hatfield, by W. Page. St Albans and Herts Architectural and Archaeological Society, 1901-1902.

One Comment