Fotheringhay Castle: The Final Dark Act of a Scottish Tragedy

There is something strangely compelling about making a pilgrimage to the site from which your Tudor heroine or hero departed this earthly life. It is where they last drew breath and uttered their last words – often with a good deal of drama surrounding the occasion to boot. To stand where a person died, and to reach through the veil of time (particularly when their death was by execution), stirs up our emotions; we cannot help but wonder at the courage these men, and women, so often showed in the face of the axe-man. One such place is the site of the medieval palace-fortress of Fotheringhay Castle – the last place of imprisonment of Mary, Queen of Scots.

Having followed Mary on her journey south from Scotland last month, stopping off at the two intriguing castles of Borthwick and Bolton, we can now explore the location that was the setting for the last act in this Scottish tragedy.

The month of February sees the anniversaries of the executions of three English queens: Mary, Queen of Scots, on 8 February; Lady Jane Grey, the ‘nine days queen’, on 12 February; and finally, Catherine Howard on the 13th day of the month. In honour of these ladies, during February, we will be touching on one significant location associated with each of them. Today, we start with Mary and her final place of captivity and execution, Fotheringhay Castle.

Fotheringhay Castle: The Power-Base of the House of York

Before we visit the site of Fotheringhay Castle and recreate the medieval palace as it was in the sixteenth century, let’s say a little about why this site became so significant. Fotheringhay would likely be of little interest were it not for the rising fortunes of the House of York, which allowed the early twelfth-century castle to be transformed into a power base for the family during the fifteenth century, after the creation of the first duke in 1385.

Richard II elevated Edmund, the third son of Edward III, to become 1st Duke of York. The same king affirmed the ownership of Fotheringhay with the aforementioned House of York. Thereafter, through the first half of the fifteenth century, the first, second and third dukes, respectively, developed the early medieval motte-and-bailey castle into a sizeable complex with luxurious privy accommodation befitting their noble status.

The 3rd Duke, named Richard, was the father of King Edward IV and, later, Richard III. The latter had extremely close ties with Fotheringhay; Cecily Neville, the Duchess of York, gave birth to Richard at the castle on 2 October 1452, and he lived at Fotheringhay for the first six years of his life. Thereafter, Richard returned for extended visits after he ascended to the throne. In an adult world, which was increasingly unpredictable and dangerous, one imagines that he must have felt a deep sense of belonging and security emanating from his childhood whenever he stayed at the castle.

Whilst palatial apartments, suitable service offices and accommodation were being built at the castle, in a separate project, the collegiate church, just half a mile or so away from the castle site, was also underway. By the mid-fifteenth century, a fine college (like an abbey), served by around 30-40 monks, was complete; it comprised the college church, a monks’ house and cloisters overlooking the Northamptonshire countryside and the meandering River Nene. Established to serve and honour the glory of the Dukes of York and their family, the monks were paid to pray for the souls of their noble masters.

It is difficult to say whether Edward IV felt as connected to Fotheringhay as his younger brother. What we do know is that this York king had the college rededicated in his name and that it was to Fotheringhay that he had the bodies of his father and younger brother conveyed. Edward had them brought to Fotheringhay after they had been hastily buried at Pontefract, by Lancastrian forces, following the Battle of Wakefield in 1460 (a battle which was part of the War of the Roses).

The two men (the latter only 17 at the time of his death) had been slain during the battle. In 1476, after the Yorks had gained the throne of England, and Edward was in a position to act, he had his father and brother reburied, as befitting their new royal status, in the York mausoleum at Fotheringhay.

There are wonderful, contemporary accounts of the reinterment at Fotheringhay, which followed a solemn procession south from Pontefract. The entire royal family, Edward IV, Elizabeth Woodville, Richard, Duke of Gloucester (the future Richard III) and all the princes and princesses of York were in attendance. Afterwards, Edward held a lavish feast at the castle, with around 15,000-20,000 people attending. The funeral feast extended over two days, and it is recorded that the poor from surrounding villages benefited enormously from the king’s largesse.

These were the glory days of Fotheringhay Castle. Perhaps because of its association with the Yorks, Fotheringhay was little used by the Tudors. Henry VIII granted it to each of his wives in turn, and Katherine of Aragon spent much money renovating and refurbishing the castle. Despite this, it was little used, except perhaps as a place for high-status prisoners like Mary, Queen of Scots. Elizabeth I visited Fotheringhay 5 years into Mary’s custody on English soil. Later, when facing trial for treason, it seems Elizabeth remembered the fortress, located reassuringly close to the country estates of two of her most ardent supporters, William Cecil at Burghley and Christoper Hatton at the equally sumptuous, Holmby House.

Fotheringhay Castle as it Appeared in the Sixteenth Century

The Surroundings, Outer Bailey and Keep

Having been cunningly ensnared in the so-called Babington Plot, Mary was transferred from Chartley Manor to Fotheringhay on 25th September 1586. She was tried over two days, 14-15 October, and found guilty shortly thereafter. But what do we know of Fotheringhay and the prison that awaited her?

John Leland, antiquary and traveller, visited Fotheringhay as part of his Itinerary in the 1530s, some 50 years before the Scottish queen arrived at the castle. He leaves us with a picture of the village and surrounding countryside, describing how, on the road toward Fotheringhay, he crossed ‘very flat meadows’ via a causeway of ‘some thirty large and small arches…enabling travellers to pass when the river overflows.’ The village, he states, ‘lies along a single street, and all the buildings are stone’. This is, reassuringly, much as you will see it today.

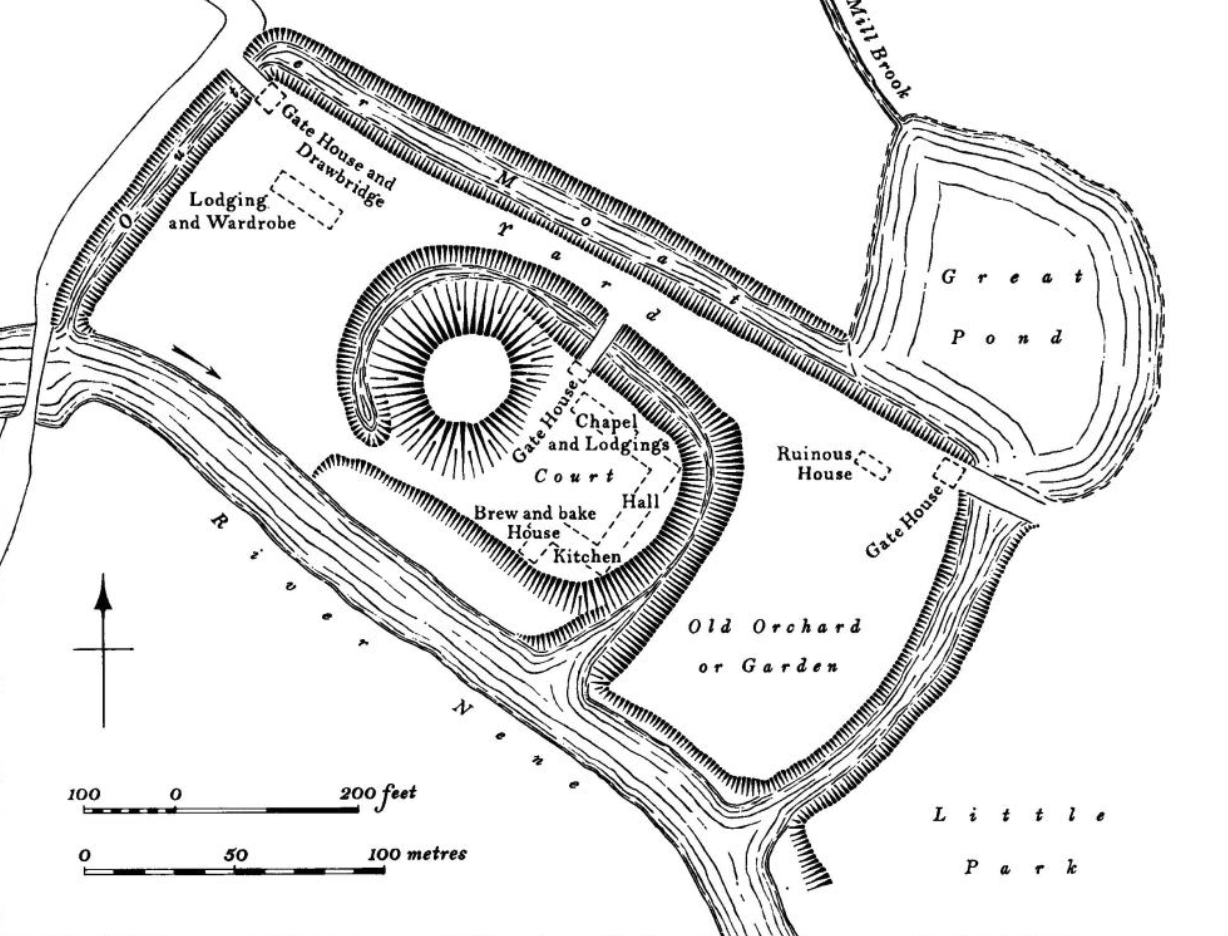

To explore the castle compound, let’s go on a tour using the map below. It shows the entrance to the castle complex via an outer ‘GateHouse and Drawbridge’. The outer moat has since disappeared, but if you are standing near this point by the bend in the road, look around and notice the fine-looking stone house nearby. It has two blocked doorways and windows visible on the end of the building, fronting onto the road. This was called ‘The New Inn’, and it is notable in Mary’s story.

Now a private home (co-incidentally of a descendant of William Cecil, Lord Burghley – how ironic is that?!), it once formed part of additional lodgings for the castle. Local folklore says that it was here, in this building, that the axe-man who was to end Mary’s life was lodged on the night before her execution. (This tidbit of local gossip was passed down to me via the churchwarden, who I bumped into whilst visiting the village!)

Follow the track forward; a slight hollow in the path perhaps gives away the site of the earlier moat. Soon, you will arrive at a kissing gate and a nearby information board. Once through this gate, you are standing roughly opposite the earlier site of the inner ‘Gate House’. Marvellously, a pretty detailed account of the layout of the castle’s buildings, made just before Fotheringhay Castle’s demolition, allows us some real insight into the lodgings used to house the Scottish Queen. Let’s walk forward, crossing the inner moat, still graven into the landscape, and pass underneath the now-lost gatehouse.

‘…as soon as you are passed the drawbridge, at the gate there is a pair of stairs [on your right I am guessing, as the description takes you up towards the castle keep on the motte], leading up to some fair lodgings and up higher to the wardrobe, and so on to the fetterlock on top of the mound on the N.W. corner of the castle, which is built round of 8 or 16 square, with chambers lower and upper ones roundabout, but somewhat decayed, and so are the leads on the top; in the very midst of the round yard in the same there has been a well, now landed up.

As far as I can see from this description, the keep on top of the tower had a round, central courtyard in which there was once a well. I am curious about the description of the keep as a ‘fetterlock’. The fetterlock and falcon was a heraldic symbol much used by the Yorks: it looks like a padlock. When you visit the Church of St Mary, you will see this symbol everywhere. Does this mean that the Dukes of York built the keep in the shape of one of the two key objects associated with their heraldry, with apartments built at the ground and first-floor levels, or first and second-floor levels, or was it just an early name for a keep? I’d love to hear if anybody has a definitive answer to that!

The Inner Bailey, Privy Lodgings and Great Hall of Fotheringhay

Having visited the keep, the description instructs us to return to the inner bailey and visit the key buildings there.

‘When you come down again and go towards the hall, which is wonderful spacious, there is a goodly and fair court, within the midst of the castle. Of the left-hand is the chapel, goodly lodgings, the great dining-room, and a large room, at this present well garnished with pictures. Near the hall is the buttery and kitchen; and at the other end of the kitchen a yard, convenient for wood and such purposes, with large brewhouses and bake-houses and houses convenient for offices. (H. K. Bonney, Fotheringhay, (1821), 29–30 from an account of 1625.)’

And so we find a large courtyard at the centre of the inner bailey. With the motte and keep behind us, the chapel is on our left, along with what seems to be the principal privy lodgings for the castle, which Leland’s account describes as ‘excellent’. These lodgings comprised at least a ‘great dining room’ and another ‘large room’ – possibly a presence chamber, privy chamber or gallery? We are not told, although galleries were often used to hang extensive collections of portraits, as mentioned in the above quote.

The reconstructive map places the hall at the east end of the site. As usual, the high end of the hall would probably have been accessed from the privy lodgings, with the low end leading to the kitchens, pantry and buttery and beyond. This is stated clearly in the above account. It seems most likely that these high-status rooms were used to house Mary for the six months that she was at Fotheringhay Castle, although, as far as I am aware, her exact place of incarceration within the fortress is unknown.

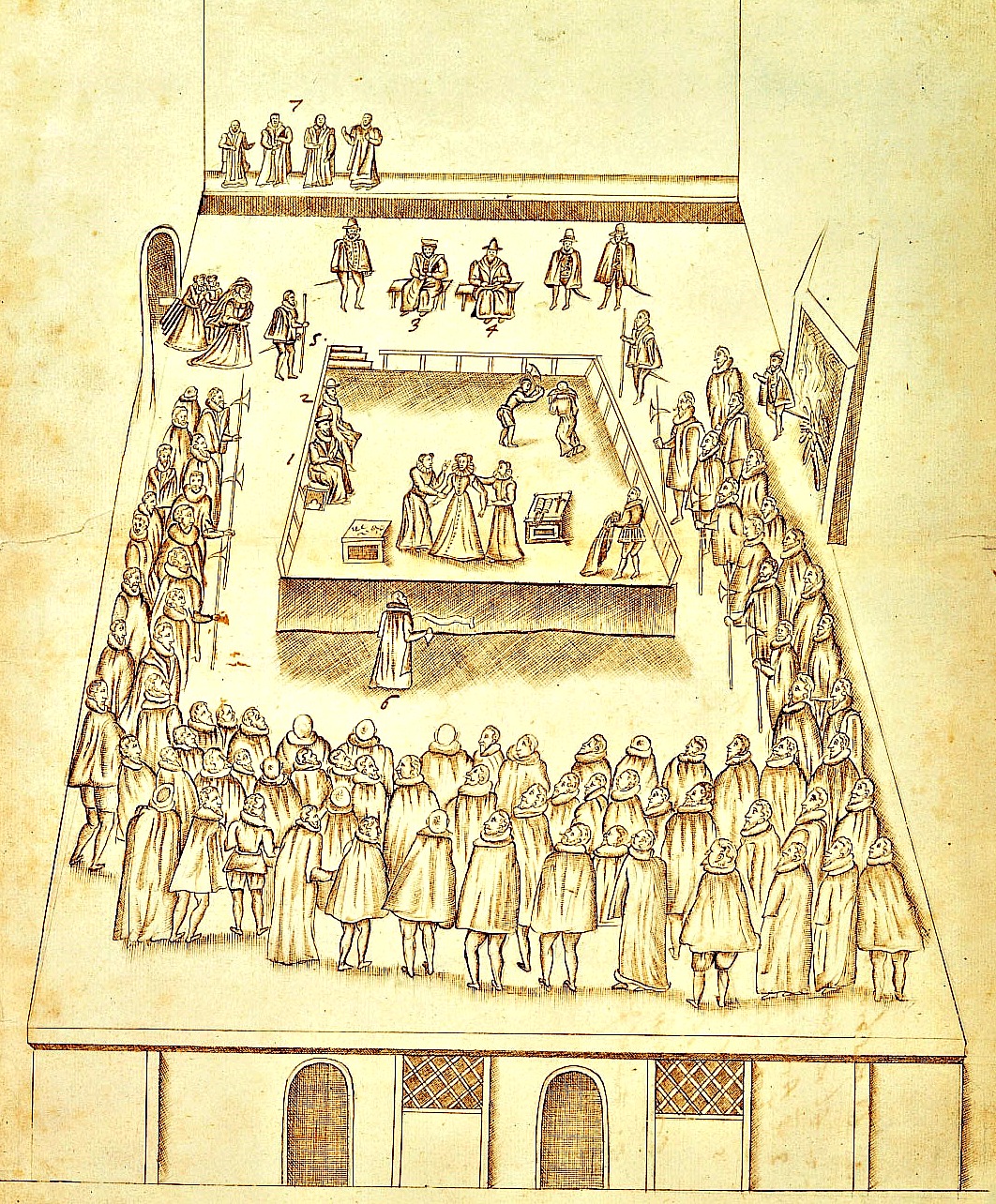

The hall itself is described as ‘goodly spacious’, and from a drawing of the execution of Mary in the Great Hall, at the upper end of the hall, we can see a raised dais and doorway – a typical arrangement. Mary is seen entering the hall through this doorway, another indication perhaps of her being lodged in the connecting privy chambers; a large fireplace is situated centrally on the opposite wall.

Inside the Great Hall – 8 February 1587

When you visit today, the boundary of the inner bailey is clear, and it is easy to walk where the privy lodgings and great hall once stood. Now, it is time to pause for a moment and connect with Mary on that, no doubt, cold February morning in 1587. With the fire crackling in the grate and to the hubbub of around 300 witnesses, Mary entered the hall. In a contemporary account, the scaffold is recorded as having been arranged at the high end of the hall. It was ‘two-foot high and twelve-foot broad’ – all draped in black. The previous evening, she had penned one of her last letters to her brother-in-law, the King of France. Here is an extract:

‘Tonight, after dinner, I have been advised of my sentence: I am to be executed like a criminal at eight in the morning. I have not had time to give you a full account of everything that has happened, but if you will listen to my doctor and my other unfortunate servants, you will learn the truth, and how, thanks be to God, I scorn death and vow that I meet it innocent of any crime, even if I were their subject. The Catholic faith and the assertion of my God-given right to the English crown are the two issues on which I am condemned, and yet I am not allowed to say that it is for the Catholic religion that I die, but for fear of interference with theirs. The proof of this is that they have taken away my chaplain, and although he is in the building, I have not been able to get permission for him to come and hear my confession and give me the Last Sacrament, while they have been most insistent that I receive the consolation and instruction of their minister, brought here for that purpose…

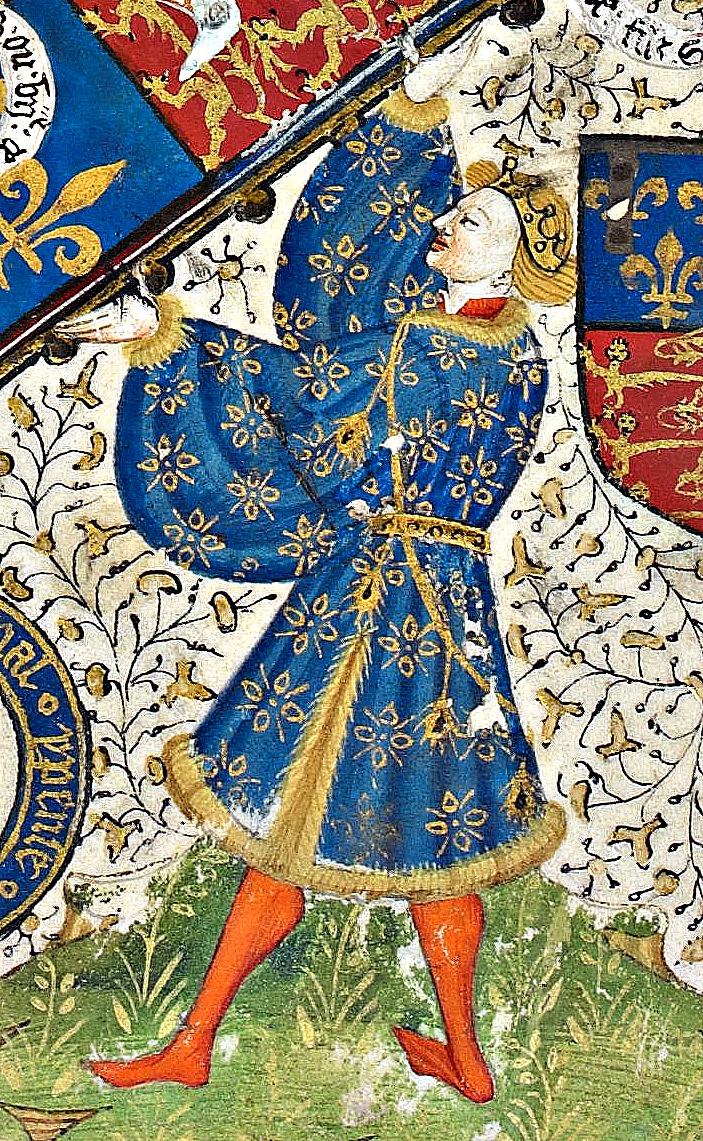

There is a detailed contemporary description of the clothes Mary wore that day, and these were captured in a posthumous and now iconic portrait of the queen as a Catholic martyr (see below). The account describes Mary’s ‘uppermost gown of black satin’, which clearly had some print upon it, and with a train which ran ‘upon the ground’. The sleeves were ‘long hanging’ and ‘trimmed with acorn buttons of jet and pearl’. They were cut such that the under-sleeves of purple showed through and, as we famously know, when her ladies and the executioners undressed her, there revealed were her kirtle of black velvet with her ‘Boddies of crimson satin and her skirt being of crimson velvet’.

After mounting the scaffold, Mary sat upon a chair while the Clerk of the Council read aloud the Commission against her, followed by a prayer said by the Dean of Peterborough Cathedral. Mary paid little heed to either, refusing to accept the invitation to renounce her religion – and expressing her willingness to ‘die therein’. She managed even a ‘smiling countenance’ when her ladies, and the executioner, helped her disrobe of her outer garments, saying that ‘she was never served by such grooms before’. Perhaps still clutching in her hand the crucifix which she had brought into the hall, Mary, Queen of Scots knelt down on a cushion, her face and eyes being covered by a ‘Corpus Christi cloth wrapped up three corner wise’.

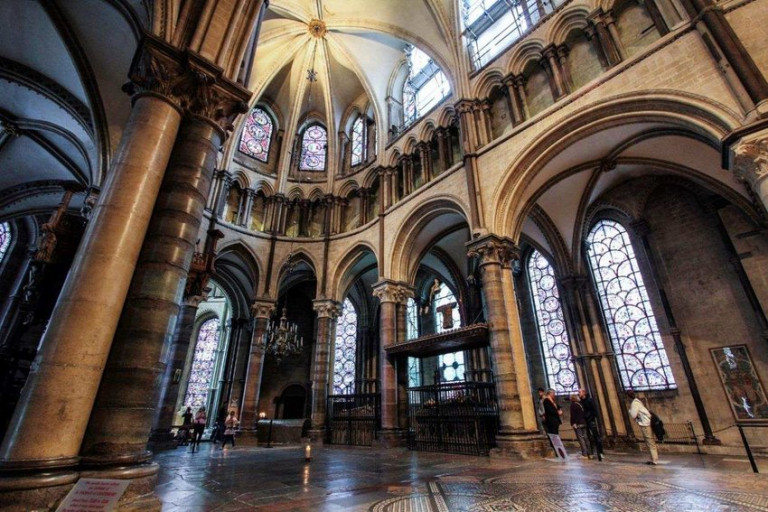

‘She groped for the block, whereon she laid her head, crying out ‘In manus tuas, Domine, commendo spiritum meum’ or ‘Into thy hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit.’ ‘At ten o’clock afore noone’, Mary was executed, thus bringing her sorry story and her ‘troubles’ to an end. After her death, Mary’s entrails were buried secretly at Fotheringhay Castle, while the body was conveyed to the ‘great chamber’ (in the privy lodgings), where the surgeon embalmed the corpse. There, Mary’s body remained until it was conveyed to Peterborough Cathedral for burial.

Today, Fotheringhay Castle is a haunting spot. As I stood upon the ground once occupied by the great hall, reliving this sad scene in my mind’s eye, only a few sheep stood by to watch my odyssey with a good deal of suspicious curiosity. Just a small fraction of the keep survives, now relocated next to the River Nene, adjacent to the site; plaques commemorating this event and the birth of Richard III speak of the immense historic significance of this now-lost palace-fortress.

Visitor Information

When visiting Fotheringhay Castle, make sure you also visit the nearby church of St Mary and All Saints, once the collegiate church of the House of York. Although much reduced in size, having lost the choir, Lady Chapel, monks’ house and cloisters at the Dissolution of the Monasteries, there is fine mid-fifteenth-century architecture to be seen, including a fan-vaulted ceiling, with the York falcon and fetterlock emblem at its centre; a font and a painted pulpit, gifted to the church by Edward IV.

The tombs of Edward IV and Richard III’s mother and father, Cecily Neville and the 3rd Duke, and that of the 2nd Duke (the only nobleman killed at Agincourt), can be seen on either side of the high altar. These are Elizabethan reconstructions of the earlier lost tombs, desecrated and left to crumble post Dissolution. They were built on the orders of Elizabeth I herself. She commissioned them after visiting the church during her visit to Fotheringhay and witnessing first-hand the sorry state of the tombs of her royal forefathers.

Also, look out for scars on the south side of the church walls where doorways once connected the main church building with the monks’ house and cloisters.

For the past 3-4 years, a commemorative service has been held in Mary’s honour, with readings in French, Latin and English. I was assured by one of the churchwardens I met on my visit that re-enactors are also present.

Having worked up an appetite, you might consider lunch at The Talbot Inn, in nearby Oundle, just a couple of miles down the road. After the castle at Fotheringhay was dismantled, stone from the site was used to construct the inn. The dark oak staircase and a large window that lights it was also brought from the castle.

There is a legend that this staircase once led up to the lodgings of the Queen of Scots at Fotheringhay Castle and that a small gate, still visible at the top, marked the boundary of her confines. Thus, it is said that it was down this staircase that Mary walked to her execution in the great hall and that it is haunted by her ghost today. As far as I am concerned, this is doubtful for two reasons.

Firstly, this is just not the kind of grand processional stair that would lead down from a ‘Great Chamber’. It’s possible, I suppose, but it doesn’t feel right. However, more importantly, ‘experts’ have dated the staircase to the early 1600s; a very good reason to suppose this tale, sadly, is just that, made up by someone to tell a good yarn. Oh well, we love a good ghost story too!

I was overwhelmed when I visited Fotheringhay. Something momentous happened there and I could sense it. The church is great too. Wonderful article.

I love it when that happens when visiting a Tudor site – or any historic site for that matter. That felt sense of connection, the energy that hangs around a place is beyond logic. Thanks for your kind words!

Fotheringhay is one of my favourite places, being a fan of both the York dynasty and the Tudors. And one can be a fan of both I assure you! There is an atmosphere around the castle area, quite difficult to describe but to me, there is an air of sadness about the place even on a sunny day. I live not far from Fotheringhay so its somewhere I have visited many times, there is definitely an emotional pull. And I can recommend The Falcon, fabulous food! Very interesting article as always Sarah! Carol

Thank you for your his beautiful essay about my favorite historical character. I’ve been researching Mary Stuart for most of my life. We are American, Scottish descendents of the Campbell clan. My Great Grandma was a Kennedy & is related to Janet Kennedy who attended the Queen. I do have a question that I hope you can answer definitively. Did one of her ladies stay with her body while it lay in Fotheringhay until her burial? Do you know which one stayed? I’m writing an historical, fictional story focusing on the betrayals she endured. It’s written from the point of view of one of her maids. Any help or guidance is appreciated, especially since I have only viewed these locations through a screen & my Grandparents stories. It makes the project more difficult but no less important a project for my Grandpa’s memory. “Never Forget” our family history & tell our story. Thanks again for this fabulous information.

Hi Shan, Thanks so much for your comment. I am so glad you liked the article. There were ladies who attended Mary; I think Mary Seaton was first among her oldest of companions and friends who stayed with her during her imprisonment. I don’t know for sure without spending time researching the answer but it would not surprise me if she wasn’t the prime candidate. I tend to focus on the places and do my research there, weaving the story into the narrative as I go, which means I often know more about the place than the people. You might try Melita Thomas from Tudor Times who wrote an article about the fate of the Four Mary’s or the Marie Stuart Society. Sorry,I can’t be of more help. Best wishes, Sarah

Just returned to the states a few days ago after my second visit to Fotheringhay. It is a magical place indeed. Loved your article and, I too suspected that the “staircase story” was just that. “Legend has it…”, but The Talbot Inn is a wonderful place for tea and musing over history, true, or otherwise.

Hi Karen! I agree…I love a good legend!